by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Jude Freeman/Flickr/CC

THE MOST POPULAR of the slate of referendums which are to be voted on this Saturday, the referendum on what name Taiwan will participate in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics under, has come under increased scrutiny in the past week. Namely, the International Olympics Committee (IOC) has warned that Taiwan could be banned from participating in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics if the referendum is successful and Taiwan decides that it would like to participate as “Taiwan” and not “Chinese Taipei” or some variant thereof. This referendum acquired more than one million supportive signatures.

Photo credit: 進擊的台灣隊-Team Taiwan/Facebook

Photo credit: 進擊的台灣隊-Team Taiwan/Facebook

It is not surprising that such a threat would come from the IOC, an organization of which China is a member and exerts a strong influence over. As with other international organizations, China uses its influence as a way to pressure Taiwan. Because of the claim that Taiwan is part of China, either Taiwan is not allowed to participate in such organizations, or Taiwan is forced to participate as “Chinese Taipei,” “Taiwan, Province of China,” or some other appellation which frames Taiwan as part of China.

Chinese pressure led Taiwan to lose the hosting rights for the East Asia Youth Games in July of this year, which were originally scheduled to take place in Taichung in August 2019. This cancellation took place in spite of the fact that the Taichung city government had already spent 677 million NTD on building a stadium for the event.

Unsurprisingly, Taiwanese athletes have become split on the issue of the referendum, with some willing to risk being shut out from participation in the Olympics in order to take a political stance for Taiwan. Others fear that their hard work and many years of training will go to waste if they are shut out of the Olympics. This includes former Olympians urging voters to vote down the referendum.

This is, broadly, the same dilemma faced by many Taiwanese working in the international world. Taishang working in China or in China-related fields face being banned from China if they express viewpoints supportive of Taiwanese independence. The Chinese government and nationalistic Chinese netizens keep a close eye on figures in the public eye, such as actors, musicians, directors, or other entertainers, threatening to shut them out of the Chinese market if they express pro-Taiwan political views.

Referendum petition signatures. Photo credit: 進擊的台灣隊-Team Taiwan/Facebook

Referendum petition signatures. Photo credit: 進擊的台灣隊-Team Taiwan/Facebook

With such concerns, it remains to be seen whether the referendum will pass. However, it is also interesting to note that the dilemma of Taiwanese athletes regarding whether to support the referendum or not is bound up with identity contestation inside different sporting organizations, such as the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee. Many sporting associations in Taiwan have historically been controlled by the KMT because positions in such associations can be lucrative and so they are given as a sinecure position to those favored by the party.

Athletes that dare to speak up against corruption or express political views that the KMT dislikes are punished through such organizations. This has resulted in younger athletes aligning themselves with younger, pro-Taiwan parties such as the New Power Party to call for reform of sporting associations.

Ironically enough, the point of the referendum on the 2020 Tokyo Olympics was always, in some sense, to fail. Referendum organizers, who were primarily Taiwanese independence activists, were no doubt aware that even in the event of a successful referendum, Chinese influence would probably result in the blocking of the name change at some point, or even provoke some unilaterally coercive action such as blocking Taiwan from the Olympics entirely.

This would provoke anger in Taiwan and it was hoped by referendum organizers that this anger could be used as political momentum to eventually push to have a referendum on Taiwan’s national status. Taiwanese independence activists have long seen holding a political referendum as a way to resolve Taiwan’s longstanding issues regarding independence versus unification, but they were only successful in lowering the benchmarks to hold such a referendum in December 2017, and even then, holding a referendum on the constitution or Taiwan’s national status is supposed to be off the table. Hence the use of indirect means such as a referendum on Taiwan’s participation in the Olympics.

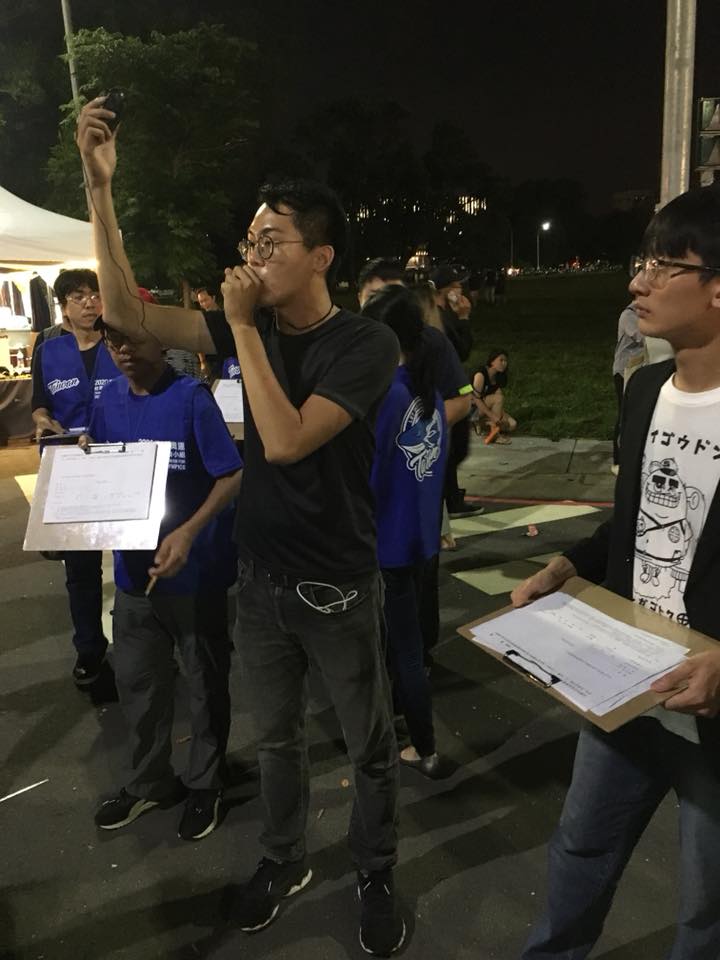

Canvassing for the referendum earlier this year. Photo credit: 進擊的台灣隊-Team Taiwan/Facebook

Canvassing for the referendum earlier this year. Photo credit: 進擊的台灣隊-Team Taiwan/Facebook

Still, as with how the DPP is sometimes blamed for what is fundamentally an issue of China bullying Taiwan, it may end up being the case that athletes and members of the public opposing the referendum out of fear that this will lead to Taiwan being blocked from the Olympics may end up blaming referendum organizers for jeopardizing their chances at competition—rather than blaming Chinese bullying. This would be far from new in Taiwan.