by Susan Chang

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Xinhua

Documenting COVID-19 in China

IN LIGHT OF the pandemic, many museums and archival institutions realised the importance of “rapid response collecting”—acting upon immediately to collect and document the effects of COVID-19 to society. Despite the infectious nature of the epidemic causing difficulties to collect physical objects, many museums, libraries, private cultural institutions as well as artists, academics and creative individuals around the world have joined forces in collecting and exhibiting pandemic related objects and stories. Collections range from everyday objects, anti-epidemic ideas, personal stories as well as a set of new objects that emerged during the pandemic to address the new reality of social distancing, lockdowns, protests and illness (eg. various types of masks, plastic bubbles placed on the dining room table, the portable seat attached to the lamp post).

The “Unity is Strength” exhibition at the National Museum of China. Photo credit: CCTV.com

The “Unity is Strength” exhibition at the National Museum of China. Photo credit: CCTV.com

In Asia, museums in China were the very first to react, but this has garnered relatively little attention compared to western counterparts. Collection and donation notices were sent out by the central and local government in as early as March. According to several Chinese local news agencies, museums across the country received many donations.

As of June 10th, the Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum has collected 729 anti-epidemic related physical objects, 20 electronic documents, 85G of video materials, and more than 1,500 photos. Among these donations, the representative ones include the “March 2020 Letter of Appreciation from Guiyang District, Incheon City, South Korea to Shapingba District”, Hubei Medical Team’s Flag Chongqing Aided by the Chongqing government”, “Sancheongsi Street Epidemic Prevention notice on January 24, 2020”, and “helmets worn by construction workers of the new Leishenshan Hospital”. These are material evidence that promote the national discourse stressed by the Chinese government that Chinese people from all sectors of society are fighting the pandemic “as one”, reflecting the spirit of the Chinese people as one which is united and not afraid of danger. Unsurprisingly, the last sentence in this narrative echoes the “Unity is Strength” Exhibition later held at the National Museum of China.

Displaying COVID-19 Objects in Museums in China

DESPITE MANY unanswered questions on the origin of the virus, the number of actual cases, in addition to the passing of the whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang who tried to issue a first warning to the Chinese government, several museums across the country have held COVID-19 related exhibitions “celebrating the victorious battle”. One which made international news is the National Museum of China. On August 1, 2020, the museum launched “Unity is Strength: An Art Exhibition on the Fight Against COVID-19”, displaying 200 works created during the COVID-19 pandemic featuring themes such as rescue scenes and epidemic prevention. The actual exhibition of “Unity is Strength” lasts for two months while the online platform continues to be accessible. One thing to note is that this triumphant his/tory was only accessible to Chinese nationals. Foreigners were not allowed to enter the exhibition hall.

“Salute! Most Beautifully Going Against the Tide” by Zhang Zhi-jian, Liu Hai-yang, and Zhang Jian. Photo credit: Chinanews.com

“Salute! Most Beautifully Going Against the Tide” by Zhang Zhi-jian, Liu Hai-yang, and Zhang Jian. Photo credit: Chinanews.com

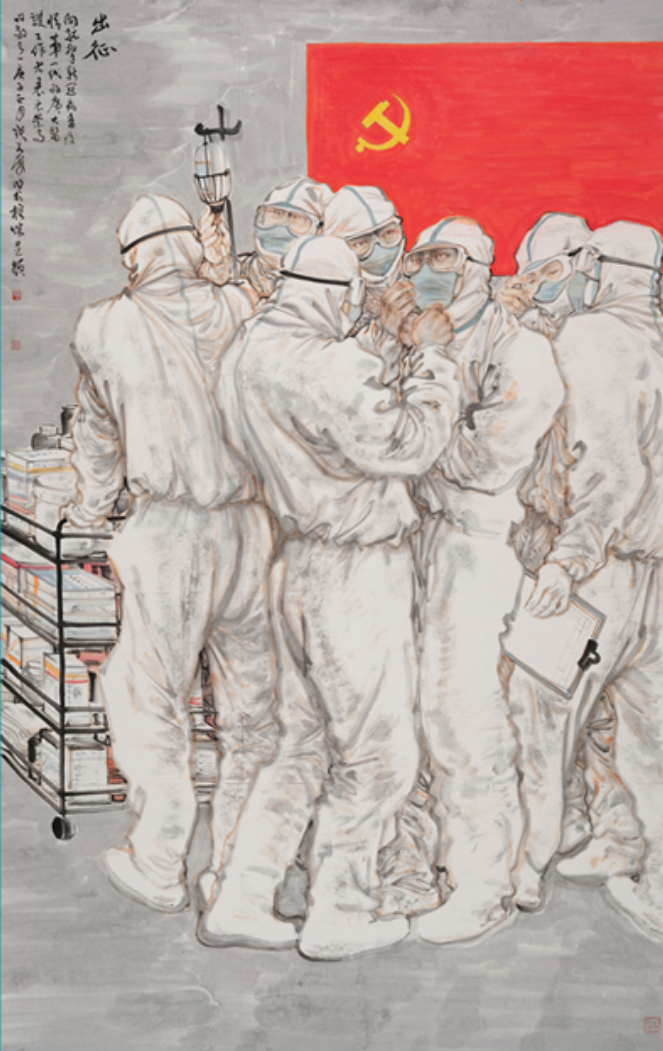

According to the exhibition website’s introductory section in August, “facing a complex situation never before seen, the Communist Party of China (CCP) Central Committee with Xi Jinping at its core put people’s health and safety first, and made overall plans for the prevention of the COVID-19 pandemic and the protection of economic and social development. It called for a nationwide effort to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus and committed to defending Hubei Province and its capital city of Wuhan from the pandemic”. It is also emphasized that this exhibition “highlight[s] China’s efforts in the fight against the pandemic through artistic works, to record the memories of the Chinese people who came together and fought the pandemic as one, and to demonstrate China’s responsibility as a major country in dealing with the outbreak of a major public health emergency.”

Through works of art, including Chinese paintings, watercolor paintings, posters, comic strips, sculptures and calligraphy, this exhibition aims and claims to realistically portray the arduous history of the Chinese people fighting the pandemic led by the Chinese government. This places Xi at the center of authoritarian power, not to mention China’s pairing of prosperity and social control. This is nothing new, as national museums are often settings for forging and maintaining political power through a dominant ideology—in this case used politically to write history and memory for a Chinese nation run by the CCP.

However, it is not just national museums rolling out exhibitions “celebrating and honouring” the combats of COVID-19, provincial museums, hospitals and schools are also collecting and exhibiting narratives of how camaraderie helped them get through hardships of this pandemic.

According to a local Chinese news report, there are more than twenty museums across the country collecting anti-pandemic objects and curating special exhibitions. One is in Sichuan. “Fighting the Pandemic-A Special Exhibition of Sichuan’s Fight against the COVID-19“ is on display at the Sichuan Museum. The exhibition is divided into four themes: “Acting on orders and implementing precise policies”, “Meritorious doctors coming forward”, “Together in the same boat” and “Strive to victories”.

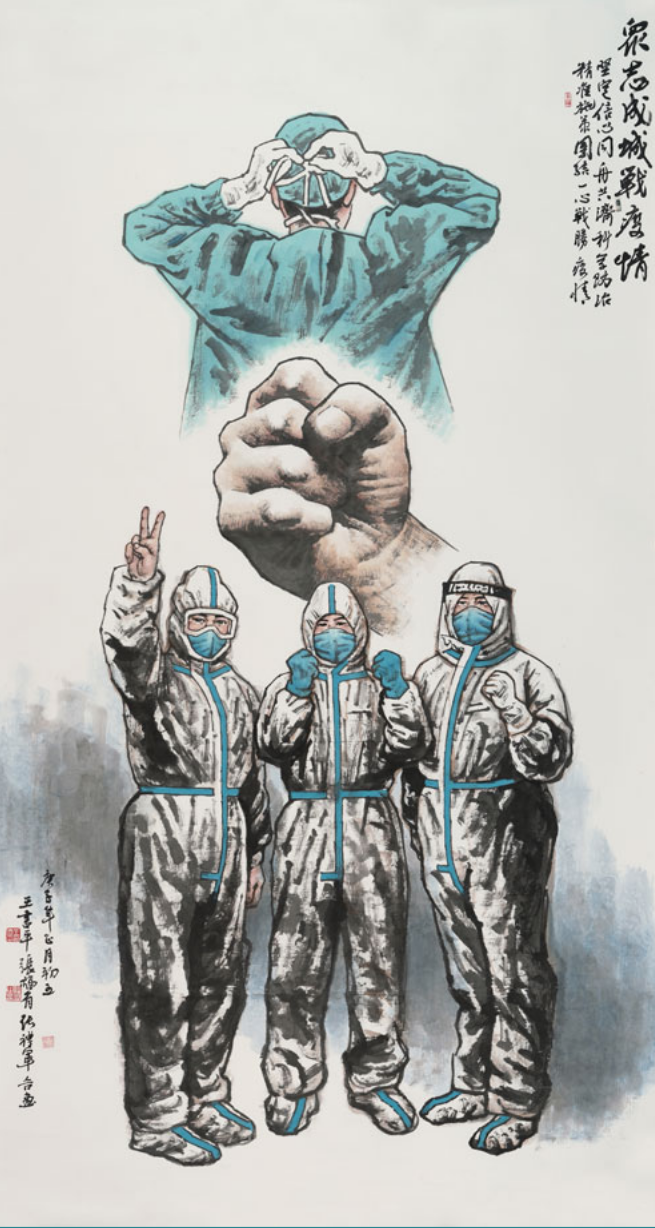

“Unity of Will is Impregnable When Fighting the Coronavirus” by Wang Shu-ping, Zhang Fu-you, and Zhang Li-jun

“Unity of Will is Impregnable When Fighting the Coronavirus” by Wang Shu-ping, Zhang Fu-you, and Zhang Li-jun

More than 1,800 collections were on display to show Sichuan people’s bravery against the pandemic. Several news reports pointed out that this is a “very cry-able exhibition”. Comments from the visitors include “everyone can be touched in their own way here”, “the anti-pandemic heroes are touching. This exhibition demonstrates China’s strong cohesion” and “Salute to the heroes! We will win the battle!” Similar narratives can also be found in other museums. They all seem to enact passion, love for their country/people, nationalism by displaying hardship, camaraderie. The narrative of these museums all reflect the same national discourse as that of the National Museum of China.

COVID‐19, nationalism, and the politics of crisis

THE CORONAVIRUS has to this date infected more than 2.2 million people worldwide. Chinese officials claim that the epidemic is under control, but their statistical standards are still being questioned. Many politicians have suggested that there is another hidden story.

Since March, China has repeatedly dismissed claims that the COVID-19 virus originated from Wuhan. Beijing continues to push back against claims of virus origin when confronted by Washington and in November 2020, China started to “push a narrative via state media that the virus existed abroad before it was discovered late last year in the central city of Wuhan, where it was traced to a seafood market”.

“Going into Battle” by Zhang Yong-hai

“Going into Battle” by Zhang Yong-hai

Adding to this never-ending drama is the continuous refusal by China to allow World Health Organization experts to investigate the origin of the coronavirus in the city of Wuhan. The WHO team of international experts were only granted permission to enter Wuhan on January 14, 2020, nearly a year after the coronavirus outbreak. Even after the team has returned from China, there continue to be disputes about the report by the investigation.

This is a critical issue for museums and historians in China, as they face “a government of denial”. The case of Chinese museums collecting COVID-19 related objects is one that demonstrates how museums easily fall prey to playing the role in disciplinary power and disciplinary society. Museum narrative matters, and in the case of collecting pandemic-related materials, it is not simply about collecting personal stories and individual actions. How we tell the narrative affects the way we use exhibits to educate the public of historical and systemic issues of epidemic diseases; and affects the way we take action to inform public policy. This is a dire problem for historians and museum communities around the world, as they are trying to piece together different evidence and stories to document a major global pandemic.

Museums need to correct and diversify the collection at the same time to be sure that they show the continuity of this kind of experience over time in a nation’s history. Museums have not historically done a good job of representing that diversity. Marginalized communities that are very hard hit by the crisis (in this case, the pandemic) are often lost in museum narratives. It is important to document various stories and experiences and not fall prey into finding a scapegoat, or create a heroic narrative for a crisis.

Government Apparatus for Rewriting History

BUILDING ON Marx’s theory of the state, Louis Althusser, in his paper “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation)”, pointed out that the state uses both “the repressive state apparatuses” and “the ideological state apparatuses” to control its people. The former includes the police, army, courts, prisons, while the latter includes ideology of religion, education, and culture. The latter reappears under “the ideology of governance, or the ideology of the ‘ruling class’ ”. Museums, falling into the category of the second apparatus, or as coined by Homi Bhabha, transform the national space into “the pedagogical memory” and “the performative memory”. They, together create a “unified” and “linear” national narrative discourse and structure consolidated by a disciplinary memory

The Chinese government has also realized the power of evoking nationalism, and in some instances alternative regional history, through cultural systems. In recent years, we see the CCP making use of its old and new museums to forge national discourses among its citizens as well as those with Chinese ancestry overseas.

Photo credit: CCTV.com

Photo credit: CCTV.com

One apparent example is the Diaoyu Dao Museum of China, recently opened early in October 2020. The Chinese state media Xinhua News Agency issued a press release today stating that the “Digital Museum of Diaoyu Islands in China” is officially being launched to help claim its sovereignty over the Diaoyu Islands. The museum consists of a lobby and three exhibition halls. The exhibits include historical pictures, film materials, documentary materials, legal documents, physical simulations, various models, animated stories, news reports and scholars’ writings, etc., showing that “according to the Chinese law and history the sovereignty of the Diaoyu Islands belongs to the People’s Republic of China”.

This case, like the pandemic exhibitions mentioned above, skillfully replacing historical truth for sentiments of nationalism and solidarity, demonstrates that museums are often instrumentalized for nationalist means—especially in an authoritarian country where multiple voices and opinions are forbidden.