by Daniel Yo-Ling

語言:

English

Photo courtesy of MIYF

This article is the third and final piece in a series covering the work of the Mixed Indigenous Youth Forum Working Group. Please also see the first and second articles of this series.

“The two Constitutional Court rulings on the Status Act for Indigenous Peoples have brought about new discussions and challenges. In the past, we have had to struggle to choose one side on a dividing line; today, we have the opportunity to break free from this dividing line, redraw new boundaries, and reject how others have drawn boundaries for us. This time around, it’s our turn to decide.”

––BUNUN WRITER and activist Talum Ispalidav concludes in the final paragraph of his introductory article written for and published in the Mixed Indigenous Youth Forum Working Group‘s (MIYF) national forum handbook. The two Constitutional Court rulings refer to the April 1st and October 28th rulings that, respectively, deemed Article 4, Clause 2 and Article 2, Clause 2 of the Status Act for Indigenous Peoples unconstitutional.

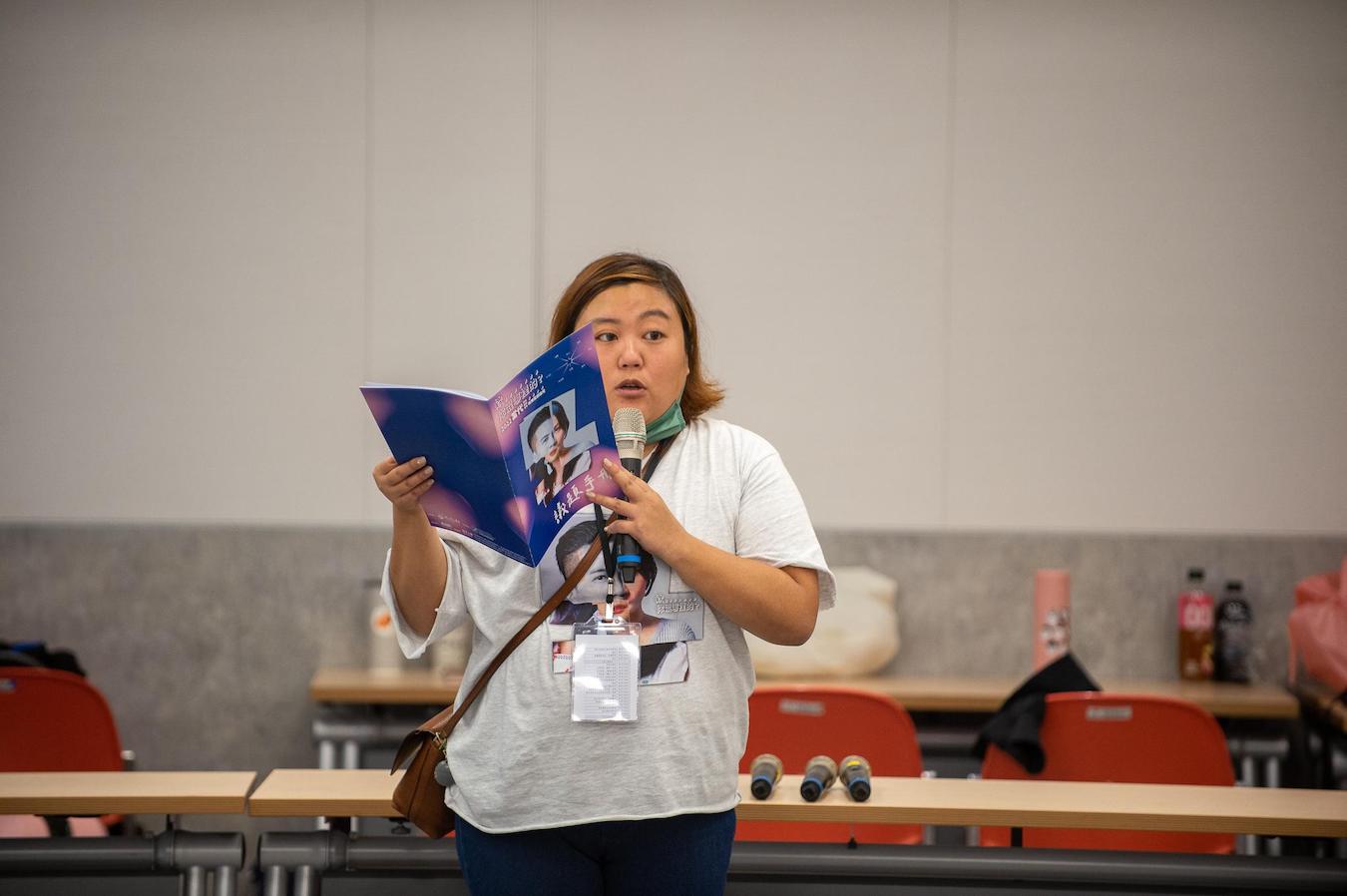

Photo of Savungaz Valincinan explaining the contents of the national forum handbook and giving opening remarks. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of Savungaz Valincinan explaining the contents of the national forum handbook and giving opening remarks. Photo courtesy of MIYF

These two rulings challenge the use of the Indigenous parent’s Han surname in Indigenous-Han families as the basis for Indigenous legal status and the exclusion of Pingpu Indigenous peoples from Indigenous legal recognition and rights, respectively requiring that legal amendments be made within two (in the case of Article 4, Clause 2) and three (in the case of Article 2, Clause 2) years. With the table set for major legal changes in the coming years, civil discourse surrounding how existing laws should be amended to recognize and accommodate the full diversity of Indigenous peoples in contemporary Taiwan has never been more crucial.

Photo of forum participants as they introduce themselves to each other. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants as they introduce themselves to each other. Photo courtesy of MIYF

On November 19th and 20th, MIYF hosted a two-day national forum in Banqiao to discuss the future of Indigenous status and recognition in Taiwan in light of this year’s two Constitutional Court rulings. MIYF organizer Savungaz Valincinan explained during the forum’s opening remarks that one of the reasons for organizing these forums was to provide a space for the voices and opinions of young Indigenous people who support the Constitutional Court rulings to be heard, and also for these people to engage in civil discourse around transitional justice and Indigenous legal reform. The national forum gathered together over 50 attendees from a variety of backgrounds including: people with Indigenous-Han family backgrounds, people with family backgrounds from multiple Indigenous groups, Pingpu Indigenous people, Indigenous people who grew up in Indigenous communities and those who grew up in non-Indigenous urban areas, as well as Indigenous people who have Indigenous legal status and those who do not.

Histories of Settler Colonial Division, Categorization, and Adjudication

AFTER A ROUND of introductions and opening remarks, Director of the Association for Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Policy Yapasuyongu Akuyana gave a lecture on the history of Indigenous legal status in Taiwan since the Japanese colonial period. Starting in 1906, the Japanese colonial administration officially adopted the previous Qing Dynasty’s distinction between “raw” (生) and “cooked” (熟) aboriginals as racial markers through the establishment of their household registration system. When Taiwan was ceded to the Republic of China in 1945, the then Taiwan Provincial Government used “high mountain aboriginals” (高山族) to singularly classify all Indigenous peoples that were previously recorded as “raw aboriginals” in the Japanese era household registration system. The classification of “high mountain aboriginals” was changed to “mountain compatriots” (山地同胞) in 1947 and was further clarified in 1954 with the passage of the Taiwan Province Mountain Status Identification Standard (台灣省山地身分認定標準).

Photo of Yapasuyongu Akuyana during his talk. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of Yapasuyongu Akuyana during his talk. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Yapasuyongu Akuyana went on to explain that the KMT regime at the time did not consider the existence of Indigenous peoples who were formerly registered as “cooked aboriginals” during the Japanese colonial period. It wasn’t until 1956 with the passage of the Taiwan Province Lowland Mountain Compatriot Identification Standard (台灣省平地山胞認定標準) that the KMT created the distinction of “highland mountain compatriots” (山地山胞) and “lowland mountain compatriots” (平地山胞) to address this oversight. “Lowland mountain compatriots” included only “cooked aboriginals” whose household registration during the Japanese colonial period was in the “plains administrative regions “(平地行政區)” and who also went to register as “lowland mountain compatriots” during registration windows in 1956, 1957, 1959, and 1963.

Indigenous peoples who failed to register were considered to have ‘voluntarily forfeited’ their Indigenous status, thought it is important to note that notification of these registration drives were not widely successful (partly due to the fact that they were made exclusively in Mandarin) and some groups may not have registered due to fear of racial discrimination or other repercussions resulting from a legal categorization that is not “human.” The Indigenous peoples who did not register as “lowland mountain compatriots” during these windows were considered “plains peoples” (平地人) without Indigenous legal status and are the Pingpu groups fighting for Indigenous recognition today.

Photo of participants listening to Yapasuyongu Akuyana’s talk. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of participants listening to Yapasuyongu Akuyana’s talk. Photo courtesy of MIYF

The distinction between “highland” and “lowland” mountain compatriots are now referred to as “mountain Indigenous peoples” (山地原住民) and “plains Indigenous peoples” (平地原住民) in Taiwan’s Status Act for Indigenous Peoples. Currently, fourteen of the recognized Indigenous ethnic groups in Taiwan have members who are registered as “mountain Indigenous peoples” and “plains Indigenous peoples,” with only the Hla’alua and Kanakanavu having members who are exclusively registered as “mountain Indigenous people.” These statistics indicate how the “mountain” and “plains” distinction is an arbitrary convenience of colonial administration that does not substantively reflect an actual difference amongst Indigenous peoples in Taiwan. Furthermore, people with Indigenous legal status in Taiwan are limited to voting for Indigenous candidates who share the same “mountain” or “plains” registration as them.

Later on in the forum, Savungaz Valincinan had attendees participate in a social experiment activity where participants stood on one side of the room depending on whether or not they agreed with a given statement. Participants were asked whether they thought the existing legal distinction between “mountain” and “plains” Indigenous peoples in Taiwan was appropriate. Almost all of the participants gathered together on the “disagree” side of the room.

Who is Indigenous? What is Indigeneity? Who Gets to Decide?

THE MAJORITY of the two day forums centered on group discussions around four main themes regarding: Indigenous legal status, cultural heritage, access to government resources based on Indigenous legal status, and transitional justice for Indigenous peoples. Conversations across these four themes inevitably blended into each other, as each of these issues are interwoven.

Photo of forum participants discussing the relationship between Indigenous identity and Indigenous legal status. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants discussing the relationship between Indigenous identity and Indigenous legal status. Photo courtesy of MIYF

The discussion around Indigenous legal status primarily centered around what kind of status requirements could be the most accommodating in place of the current Han surname basis. A range of views were expressed, such as requiring some form of traditional Indigenous name or even language tests to only requiring proof of direct Indigenous heritage. One participant even suggested the possibility of claiming Indigenous status based on a relatives’ Indigenous legal status in the event that one’s direct family line for some reason did not have Indigenous legal status. Others brought up the importance of some form of cultural participation, either through practices such as tattooing or attending their tribe’s festivals.

Another point that was brought up throughout the discussions was the importance of recognizing that some urban Indigenous peoples might not have had opportunities for cultural participation, Indigenous language acquisition, or even have a substantive relationship with their family’s tribal community of origin; hence, it is important to keep these factors in mind when considering which Indigenous legal status requirements are established. Some participants also shared their dissatisfaction over the current system’s inability to accommodate Indigenous people of multiple Indigenous backgrounds and expressed their hope that future frameworks for Indigenous legal status would be able to accommodate multiple Indigenous group registrations.

Photo of Bauké Dai’i during the national forum. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of Bauké Dai’i during the national forum. Photo courtesy of MIYF

There was also much discussion on how to ensure the recognition of Pingpu Indigenous groups who are not recognized as Indigenous by the government and thus are not subject to legal rights and protections. Currently, since Pingpu groups do not have Indigenous status, they are not covered by Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples Basic Law. Regarding the government’s proposal to create a third “Pingpu Indigenous peoples” category alongside the existing “mountain” and “plains” Indigenous peoples framework, some participants shared that they thought the entire “mountain” and “plains” classification system should be abolished rather than consolidated with a third “Pingpu” category. One Makatau participant expressed their discomfort with the term “Pingpu,” which is a term of convenience created by the Japanese and later taken up by the ROC. With regards to cultural heritage, this same Makatau participant shared that their clothing and festival traditions are still intact, echoing MIYF organizer Bauké Dai’i’s remarks about Kaxabu language and customs. Hence, the notion of Pingpu Indigenous peoples as being completely “sinicized” is false.

Photo of forum participants discussing the relationship between Indigenous legal status and cultural heritage. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants discussing the relationship between Indigenous legal status and cultural heritage. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Discussion around Indigenous cultural heritage emphasized that “culture” includes much more than just language. Weaving and beading practices, Indigenous foodways, botanical knowledge, cosmologies and rituals, in addition to language, are just some of the aspects that constitute the complex and dynamic coherence that is ‘culture’.

Many participants concluded that, in light of a fuller understanding of Indigenous cultural heritage and practices, the idea of linking Indigenous legal status or access to government resources reserved for Indigenous peoples with an Indigenous language proficiency exam is preposterous. Furthermore, one participant brought attention to the fact that language proficiency examinations tend to homogenize the linguistic diversity of Indigenous languages for the sake of standardized cultural transmission, citing the example of the Isbukun dialect of the Bunun language dominating the other four dialects of Bunun currently spoken in terms of teaching and testing materials.

Another participant also brought up the example of Amis traditional clothing originally being black but being forced by the Japanese to red because it was more “festive” and thus tourism-friendly to draw attention to the fact that culture is always changing and adapting. Given the inherent difficulties of standardizing a singular notion of “cultural heritage” for the sake of establishing it as a requirement for Indigenous legal status, discussions tended to return back to family descent as the best way to adjudicate Indigenous status.

Photo of forum participants discussing Indigenous legal status and access to government resources. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants discussing Indigenous legal status and access to government resources. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Regarding access to government resources set aside for people with Indigenous legal status, the national forum handbook explains that the current legal opinion expressed by the Constitutional Court justices tends towards finding a way to separately explore the issues of Indigenous legal status and government resources set aside for Indigenous peoples. Accordingly, many participants discussed their experiences with and thoughts on access to government resources.

Some participants expressed the idea that the framework of Indigenous reserve land arises from a logic of private property that is foreign to Indigenous groups, citing the example of how a significant number of Tao people have not registered their reserve land parcels because they operate off of different understandings of land as collectively shared. These logics of private property and individual ownership rights were considered to be a major factor behind recent demands that Indigenous reserve land be made available to Han people for purchasing and selling. Participants noted that such ludicrous demands arise from a fundamental misunderstanding of Indigenous reserve land, educational subsidies, affirmative action measures, and other forms of government resources made available to Indigenous peoples as a form of government assistance (補助) rather than an issue of reparations (補償) tied to Indigenous transitional justice. One participant noted that even financially well-off Indigenous people still bear the historical trauma of settler colonialism.

Photo of forum participants discussing Indigenous transitional justice. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants discussing Indigenous transitional justice. Photo courtesy of MIYF

During discussions on transitional justice, the case of the Amis Tafalong Kakita’an ancestral house reconstruction project in Hualien county was brought up as an example of how transitional justice involves a complex set of negotiations and consensus-building processes that center the desires of contemporary Indigenous peoples in determining what constitutes justice. The reconstruction project, famously documented in anthropologist and filmmaker Hu Tai-li’s documentary Returning Souls (2012), started in 2003 with the request of a group of young Amis from Tafalong to repatriate large wooden pillars from Academia Sinica’s Institute of Ethnology that contained the souls of the Kakita’an family’s ancestors so that they could rebuilt the Kakita’an family’s ancestral house, which was destroyed in 1958 by Typhoon Winnie.

Through a series of negotiations, an agreement was reached to leave the wooden pillars at the Institute of Ethnology for preservation but to return the ancestors’ souls back to Tafalong and carve new wooden pillars in the reconstructed house. In 2004, a pig offering and ritual was performed to transfer the ancestors’ souls back to Tafalong, and in 2006, the Kakita’an ancestral house and newly carved wooden pillars were completed. Forum attendees brought up this case to draw attention to the fact that coming to internal consensus within Indigenous communities requires deliberation and that the outcomes of transitional justice are not pre-set, but rather emerge from these consensus-building processes. Throughout this process, the desires and subjectivity of contemporary Indigenous peoples are paramount, as opposed to some abstract and universal idea of what transitional justice should look like.

Photo of forum participants engaged in group discussion. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants engaged in group discussion. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Discussions around transitional justice also emphasized the importance of rehabilitating Taiwan’s history through the perspective of Indigenous peoples. For instance, such rehabilitation would involve teaching the history of Taiwan’s settlement through Indigenous people’s experiences of settler encroachment, understanding the February 28 massacre as a continuation of settler colonial violence that long precedes KMT rule, and critiquing the Han-centrism of Taiwan nativist literature. These points were emphasized in an attempt to bring to mind the importance of not only developing an Indigenous historical outlook on Taiwan, but to suggest an outcome of transitional justice involving the history of Indigenous peoples in Taiwan becoming the focal point of “Taiwan history” itself rather than just a specialty topic. The implication of this suggestion was that all of Taiwanese society would need to recenter Indigenous peoples in their understanding of the past in order to collectively move towards a future where Indigenous transitional justice can be realized.

The Future of Indigeneity

EXISTING DISCOURSE on legal reform of the Status Act for Indigenous Peoples, which have been dominated by older Indigenous elders and scholars, have tended to conflate broadening Indigenous legal status with diluting government resources. One of the main reasons MIYF organized this series of forums is to make an intervention into civil discourse on Indigenous status and recognition by drawing attention to the experiences and voices of young Indigenous people from a variety of mixed backgrounds. In other words, the MIYF forums have made a much needed intervention in public discourse on the future of Indigeneity in Taiwan by dispelling myths (such as “Indigenous population in explosion” and “sinicized Pingpu groups”) held by those who oppose Status Act reform.

On another level, the MIYF forums have provided a space for young Indigenous people who support Status Act reform to gather together and converse about what specifically they hope for in the future, how the issues of Indigenous status and recognition should be understood, and how the broadest range of Indigenous peoples with diverse backgrounds and identity journeys can be accommodated. As one forum participant shared at the end of the last day, they did not have opportunities when they were younger to share their experiences as a mixed background Indigenous person and discuss how these experiences connect with the need for legal reform. Perhaps the lasting success of the MIYF forums is in providing a space for younger Indigenous people to gather, connect with each other, and engage in the process of consensus-building around what a new system surrounding Indigenous legal status and recognition might look like.

Photo of forum participants engaged in discussion. Photo courtesy of MIYF

Photo of forum participants engaged in discussion. Photo courtesy of MIYF

In the future, MIYF will continue organizing similar forums on contemporary Indigenous issues including and beyond Status Act reform. These spaces will provide a new generation of young Indigenous people with an opportunity to engage in civil discourse and consensus-building around the issues that affect their lives most. Regarding the future of Indigeneity in Taiwan, it’s their turn to decide.