by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Hong Kong National Party/Facebook

THE ANNOUNCEMENT yesterday by the Hong Kong government of the banning of the Hong Kong National Party (HKNP) should surprise few. Namely, the Hong Kong government had previously intimated in July that it would move to crack down on the pro-independence party by opening a period for public comment by the party to defend why it should not be banned.

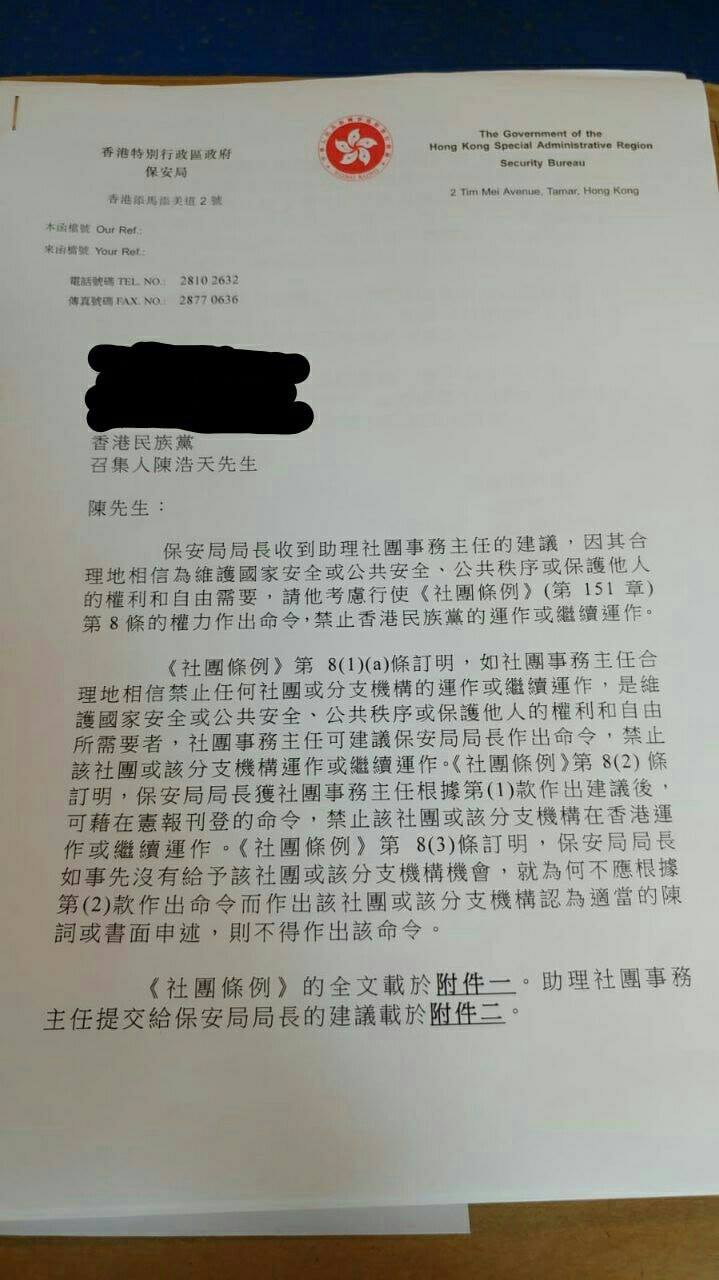

First page of the letter received by the Hong Kong National Party announcing the planned ban but giving the Hong Kong National Party a period of time to respond and justify its existence. Photo credit: Hong Kong National Party/Facebook

First page of the letter received by the Hong Kong National Party announcing the planned ban but giving the Hong Kong National Party a period of time to respond and justify its existence. Photo credit: Hong Kong National Party/Facebook

Although the HKNP did submit comments to argue as to why it should not be banned, the ban would come in the form of a short statement in the government’s official gazette. For its part, the HKNP attempted to use news of the impending ban to raise awareness of increasing political restrictions in Hong Kong, with party convener Andy Chan giving a speech at the Hong Kong Foreign Press Correspondent’s Club in August in which he urged other countries, such as the United States, to take actions against actions by the Hong Kong and Chinese governments. Unsurprisingly, the Hong Kong government and pro-Beijing groups in Hong Kong were highly condemning of the Hong Kong Foreign Press Correspondent’s Club for allowing Chan a platform to speak.

As such, the banning of the party marks the further deterioration of political freedoms in Hong Kong after previous actions by the government to prevent pro-independence candidates for running for office or to invalidate the electoral victories of pro-independence candidates after they had taken office. However, the move by the Hong Kong government still opens up a number of questions as to what steps the Hong Kong government will take next, acting as Beijing’s proxy in Hong Kong.

For one, it is a question as to whether the Hong Kong government will move to ban further political parties or organizations which oppose Beijing’s rule from afar over Hong Kong. This could expand to include banning political parties and groups which have not adopted rhetoric as radical as the HKNP in calling outright for Hong Kong independence, but which protest Beijing’s actions deteriorating of Hong Kong sovereignty nonetheless, such as Joshua Wong’s Demosisto party.

Rally by the Hong Kong National Party. Photo credit: Hong Kong National Party/Facebook

Rally by the Hong Kong National Party. Photo credit: Hong Kong National Party/Facebook

At the very least, the banning of the HKNP gives a taste of how Beijing will frame other political bans in the future. This can be observed in attempts to claim that the HKNP was a violent, radical, separatist party and that banning the party is merely for the sake of protecting public security, rather than as a means of cracking down on political dissent. While as primarily a student group, the HKNP was by no means as dangerous as Beijing claims, there is no doubt that future bans of other political groups—even more moderate ones—will be justified similarly.

Nevertheless, it remains to be seen as to what actions Beijing will take against the HKNP in the near future, such as whether Beijing intends to go the full measure of arresting HKNP members. The ban stipulates that HKNP members continuing to congregate could be arrested for up to three years, but it still remains an open question as to whether the Hong Kong government would take the full measure of such actions.

Such arrests would not be surprising, given arrests of other pro-independence activists by the Hong Kong government in the past year. The most famous of these arrests would be the arrest of prominent localist Edward Leung, formerly the spokesman of the pro-independence Hong Kong Indigenous, on charges of rioting and his current jail sentence of six years in prison, but there are a number of lesser-known examples, including incidences of Hong Kong localist youth activists having fled Hong Kong.

Yet if the Hong Kong government does pursue such arrests, this will certainly set a precedent for how it handles other political groups in Hong Kong. Likewise, all this goes to show that constitutional rights in Hong Kong have long ceased to exist and that these prove no defense against political repression by the Chinese government.

Photo credit: Hong Kong National Party

Photo credit: Hong Kong National Party

In the meantime, it proves highly likely that actions by Beijing will actually give further credence to the idea of Hong Kong independence rather than contribute to it’s being stamped out as a political ideology in Hong Kong. After all, the notion of Hong Kong independence is actually fairly new in Hong Kong, having been only a minor force in even outbreaks of resistance to Beijing in the past, such as the Umbrella Movement, and the HKNP is actually rather small in number.

But unprecedented political actions by the Hong Kong government against pro-independence groups prove that Beijing takes pro-Hong Kong independence activists seriously as a threat. And this may give the idea of Hong Kong independence more credibility as a political ideology going forward.