by Symin Chan and Brian Hioe

語言:

English /// 中文

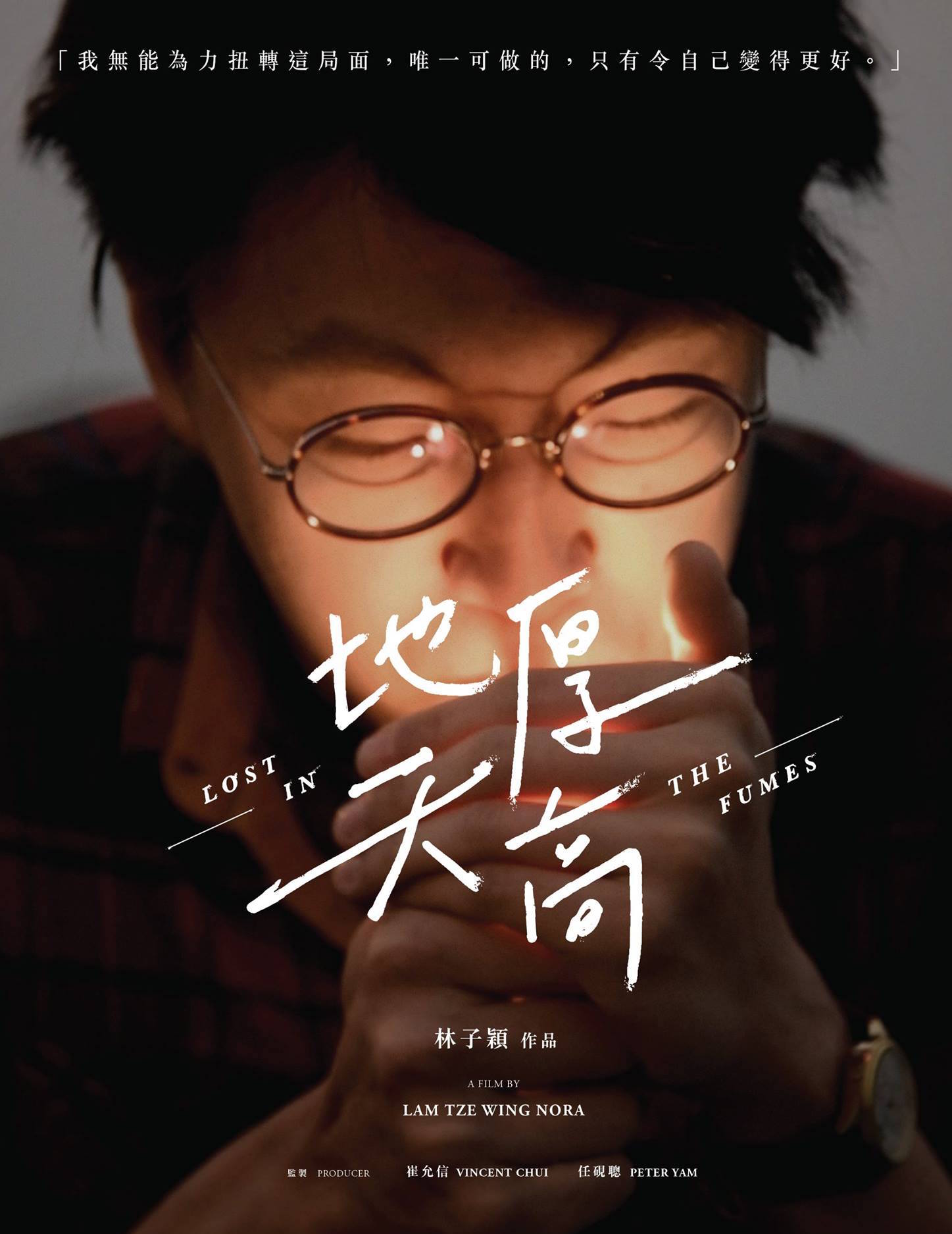

Photo Credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Translator: Brian Hioe

Nora Lam is most recently the director of Lost in the Fumes, a documentary about Hong Kong localist Edward Leung. Lam has also worked on films including directing Midnight in Mong Kok and co-directing Road Not Taken.

The following interview was conducted on May 9th by New Bloom editors Brian Hioe and Symin Chan during a visit by Lam to Taiwan.

From Journalism to Documentary Filmmaking

Symin Chan: What do you choose to use a documentary film as your means of participating in this movement? You may have, for example, began as a social movement participant yourself.

How do you regard your own role? Have you ever felt that you should put down your camera and participate with them during the movement? Or did you feel that you should record these things in an objective manner?

Nora Lam: I think that this is quite related to my background. It’s correct that, a long time ago, I went to social movements as a participant. But that was when I was younger, such as in my later years of middle school or high school. That year, it was the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square incident in 2009. Many Hong Kong peoples went there to support that.

My family didn’t pay too much attention such issues. I was an obedient student while in school, although I wanted to go. I only began to actively participate later on. The Tiananmen Square commemoration in Hong Kong mostly consists of sitting down and participating. As a sixteen-year-old, it was quite a large thing. I also went to the July 1st commemoration, to look around.

Looking back now, I would realize that I did, actually, in some sense participate on the surface level. But I feel that I didn’t know too much about those issues then, that I just wanted to go.

I think that I only began to truly understand social movements in my freshman year of college, when I participated in the campus television network at Hong Kong University. I was a reporter. That had a large influence.

Photo credit: Ming-Siou Tsai

Photo credit: Ming-Siou Tsai

I had grown up in an isolated environment and, as a reporter that year, I had the opportunity to deepen my understanding of society. To go onto the streets, to get to know people, to see things firsthand that I had only seen on television before, to record, to edit the film, to write report on what had happened. I think that opened my eyes a great deal. In the past, I might have simply felt that walking in the middle or in the back of a protest might count as a form of participating.

It was in 2014 that I was a campus reporter, and what students paid attention to was the student movements of that year. That was the year of the Umbrella Movement. So I had the opportunity to get to know student leaders then, such as heads of student associations, or others.

I had the opportunity to get to know people I had previously only been able to see on television or in the news. I came to understand how they planned and organized protests and to see how this movement started from zero and developed. What problems that the movement might have internally and externally, as well as what distinctions they made in their judgments. Because many of my friends were participating in social movements, as a result of which I heard about events that took place.

So my participating began as a journalist, apart from participating in Tiananmen Square commemorations when younger. Now, I no longer record news, and I rarely make documentaries regarding political issues in these past few years.

It’s only in these past few years that I have begun to participate again as a regular “participant,” then. It’s quite interesting, because I had forgotten what it feels like. In the past, when i was in front, I was always holding a camera, and I would always have to stand in the front, watching how the police were behaving, or how leaders were organizing actions.

In that way, to respond to your question, I didn’t begin as a participant. I was very clear about what I wanted to do as a journalist,

But when I started, there were some times that were hard to endure. Such as during the Umbrella Movement or during the movement events before the Umbrella Movement that many people participated in, seeing as my classmates were there, and I might see them being dragged away by the police or hit. This was hard to endure, because we were all the same age, and it was quite strange for me to be standing there, watching, while they were being hit.

Yet I never felt conflicted about being there. I had to confront this reality, of filming there. I decided endure this difficulty.

SC: You felt that as someone documenting things, you had to endure this.

NL: Yes. Also, as a journalist or documentary filmmaker, I found that I enjoyed filming and editing.

My interest in my current career began from filming or photographing as a journalist and reporter. For example, during the Umbrella Movement, I also was taking photos as a journalist. When in front of the action, I sometimes felt very excited when the police fired tear gas, because the scene was very photogenic. I had a feeling that I was recording history. Or that the photo was composed well.

Or sometimes, as a journalist, when many people were discussing my report, I would also feel elated. But I knew that this feeling of elation was the result of other people’s suffering.

News is a very contradictory thing. The worse a piece of news is, the larger it is. As a journalist, or as a documentary filmmaker, the more tragic story you are filming, the more successful you are.

I felt that this was contradictory starting out and I still feel this way now. I have to admit that I have benefitted from this. That I have gotten things I want out of this. Such as opportunities to film.

Talking with a friend, I once compared this, jokingly, to the blood-soaked mantou in Lu Xun’s short story, “Medicine.” That I have gotten benefits from other people’s pain. Sometimes it’s hard to stomach. I sometimes hate that I am doing this kind of work, but there’s no other way.

I commented this to a friend this when I was showing them different accessory stories in Taipei and how nice they were, that I had the opportunity to travel to Taipei because of my film. That I have had these opportunities. While on the other hand, Edward Leung is already in jail.

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Brian Hioe: For you then, what do you find meaningful about being a journalist or documentary filmmaker?

NL: I think both journalism and making documentary films have about the same meaning to me. What I prefer to do is to tell stories. Why i wanted to film Edward Leung is because, from the standpoint of storytelling, this is a good story. That people should hear this story.

I studied literature when i was younger, in middle school and high school, and I studied comparative literature in college. From the standpoint of looking at it as a text, I felt this was quite worthwhile, which was why I wanted to do this. But news is different. You think, “This is newsworthy, this is something that people should know.”

For example, when I filmed Edward Leung’s struggles with depression, this is not newsworthy. Or filming Edward Leung playing sports is not newsworthy. As a journalist, I would not feel that this is worth documenting. Some of my journalist friends felt disappointed after watching my film, because they might have wanted to see an analysis of the localists, or of Hong Kong independence. They felt less interested that it was focused on an individual’s personal feelings.

Yet I felt that my story, in terms of character and emotion, was worthwhile. There was a conflict between filming things with news value and what I wanted to focus on in filming him, such him talking about enjoying playing the guitar and wanting to be a singer-songwriter, or things like that. I also did film him explaining his views on localism, but I didn’t put that into the film, because I felt that this was not related to the subject of my film.

Consequently, from the point of view of news making, the film does not have news value, but if I want to focus on a character and that means my film does not have news value, I think it has to be that way.

SC: So in terms of later works, would you want to work on fiction, then?

NL: I am currently working on scripts now. I just finished another documentary, but it is also character-focused. It’s not a very political approach.

Edward Leung

BH: How did you begin filming Edward Leung?

SC: Likewise, was there anything in the filmmaking process which was different than what you expected? Why did you pick Edward Leung in particular?

NL: I’m a very instinctual person. I had a sense of affinity to him. Almost like encountering someone you are chasing after–not in love though, but in seeking a subject for a documentary. [Laughs]

In first half of 2016, I had finished my first full-length documentary, Road Not Taken. After that, I had a lot of time, so I was thinking about what I should film for my next documentary. At that time, the Mong Kok incident took place. Edward Leung had just become well known then by standing for election. He was also at Hong Kong University and many of my friends around me supported him, and acted as his volunteer staff. I thought that this was quite interesting, so I went to take a look.

I was there at Mong Kok as well, so that left a deep impression on me. One night, I went to one of his campaign rallies. I was originally just curious, but I felt quite moved. That wasn’t because of his political views particularly, but because he was very passionate.

It was like a May Day concert or something. When he was at the height of his popularity in Hong Kong, people looked at him as though he were a rock star. That whatever he did became very famous.

I felt that the atmosphere there that day was very worth recording. He could move people. So I wanted to film this. As a result, Edward Leung naturally became the first person I wanted to film.

I originally thought of trying to find several people to compare and contrast them, but as gradually got to know Edward Leung and got to know his story, his unhappiness in participating in politics, his conflicts, and his dreams, I thought that this was enough to support a full-length documentary. It was a very smooth road towards this. There wasn’t very much planning.

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

SC: Was there anything that you did not expect while you were filming him?

NL: My first impression of him was that he was like a rock star. That was in February. I went and talked it over with him in March and April. Very quickly, he told me that he wasn’t someone who knew what he wanted to do, that was welcomed everywhere, that internally, he felt very lost and confused. He also told me that he wasn’t too happy to be participating in politics. That was quite shocking to me.

Because when he told me this, that was at the height of his popularity. From my prior understanding of politics, it was very surprising for me to see that he was unhappy despite being so popular. The first time I discovered this side of him, it was very different from what I expected. I had thought of him previously as being a very passionate person. Yet he showed me his more depressed side. It was also quite shocking that the government did not allow him to run. In 2016, everyone thought he would win.

I originally thought that politicians would become fake over time. That for the sake of glamorous things, they would forget their original values. I talked about this with him, before he participated in elections. “If you get into LegCo, do you think that you will change?” He said, “ I think that I will, because right now, I am already changing.” This is all in the movie.

So I said that, “Okay, I will film you becoming a–in Cantonese, we call it a ‘zing-gwan’ (政棍). I film this process of you starting of from being very naive and pure, then becoming rotten.” And he was like, “Sure! Film this.”

Then he was DQ-ed and not allowed to participate in elections. The government took away his opportunity to become a “zing-gwan.” [Laughs] For a few weeks, it was quite chaotic. When I am filming, I am used to planning this very thoroughly, that in the first week I’ll film this, that in the second week, I’ll film this, that on the day of elections in September, I’ll film this. But then my story suddenly changed.

Edward even mentioned that during a television interview. He mentioned that someone was making a documentary on him participating in elections, but that now he was unable to participate in elections, so that this person was unsure of how to keep filming. [Laughs[

BH: I recall that he said once that if he ever changed, he should be forced out of office.

SC: In the process of filming, how did you get to know in Edward Leung? In the film, he discusses a lot of his personal views and feelings. Or other political participants along with him.

NL: I think it’s quite ironic. A lot of journalists have asked me this before, that they wonder why he would have faith in me, or why he would say so many things so directly, or would be so blunt. I started to film him in June 2016. He knew what my last work was, because I invited him to a screening of mine, and asked him afterwards if I could film him.

He was quite popular then. Hong Kong Indigenous offered to hold screenings of my film, afterwards, so we held a screening for my film. Many people came to watch, but not to watch my film, instead to see him and Ray Wong Toi-yeung, these two stars. I remember that night, my friend said that my dress was very beautiful. I remember that I had worn the same dress two years earlier to go to a screening organized by Edward Leung.

An audience member asked me an interesting question, because my previous was about how two of my classmates at Hong Kong University confronted the failure of the Umbrella Movement and what they did after. One of them later became famous, because he became head of the student association at Hong Kong University and he had some conflict with the school administration. So when you know these two people for such a long time, what kind of changes take place in your relation with them?

Edward Leung was there at that screening, as were these two previous main characters of my film. I said that I’ve known my friend, who was head of the student association, for very long. I knew that he was very simple before he became involved in politics, who would be joking around or talking about girls, or talk about things like that.

That year, he became very famous, and there was a lot of pressure, because the school hated him very much. And so in those years, he became very restrained. He would be less happy and he couldn’t talk as freely. I knew this, because I had been filming him. Before, he was very open. Then, you would have to chat with him about some non-topics for fifteen minutes before he’d relax, and tell you what he was thinking.

That night, Edward Leung called me–before, I didn’t feel that he especially went out of his way to let me film, that sometimes he could be hard to contact, and he usually just responded to my messages by text, and he didn’t call me–he called me and said, “Hey Nora, when I heard you talking about the main character of your last film, I felt quite moved. Because that’s what happened to me as well.”

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

I think that sense of trust began from there, that he felt that there was someone who didn’t just pay attention to what took place on the surface, but looked deeper inside, and that because I could understand my other friend, I could understand him as well.

Edward is quite a sincere person. In the beginning, it was hard to gain his trust. And he said things quite bluntly to anyone, not just me. I said that other journalists as well. And right now he is in jail, so I can say anything I want. Maybe when he is out and you ask him, he’ll say instead, “Nora was actually quite annoying!” [Laughs]

SC: Hopefully we’ll have the opportunity to ask him in person sometime.

The Challenges of Filming

SC: What challenges did you face while filming?

NL: This is a boring answer, but I have to say, the toughest issues for me were technical issues and funding. In Hong Kong, it is very difficult to make creative works. Hong Kong is a highly commercialized city. Everything is very expensive. And Hong Kong parents don’t like you to do things which don’t make you much money. My mother and father are quite traditional Hong Kong people. It’s a very middle class society.

It’s hard to get funding for this kind of project. But I was very fortunate to meet one of the current producers for the film in the process of making it. He sponsored me.

Likewise, although I had several years of experience filming before this film, many things were new for me. There were many technical issues and because my friends were all comparative literature students, as well as because Hong Kong University doesn’t have a filmmaking program, oftentimes I would find myself looking up “How-to” tutorials on Google.

Lost in the Fumes had technical issues, as well as budget issues. But sometimes I feel quite proud of the fact that I learned these things on my own. That I didn’t learn from school or use preexistent connections I had.

These are issues on the production side. On the personal level, I think it is hard to decide on the direction of a documentary. And you are using other people’s stories, but it was that I felt this story was worth telling, that of Edward Leung.

However, from the point of view of other supporters of mine, they may not always feel it is worth telling, or if I go in a different direction than they had hoped, it feels a bit like I tricked them, or that I took advantage of their faith to do what I wanted to do.

And for this to be seen may not be so good. If Edward Leung were to eventually become a politician, that this film might actually have a negative impact on him. They might have seen me as a friend, but I also may look at them differently.

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Like you are interviewing me now, but you’re not just chatting me just to be friendly either. 30% or 40% of your brain might be thinking about the interview, such as how you should write about this, or how I should edit this film, to use this line of dialogue or not to use this line of dialogue.

You think about these practical issues in interacting with people. It’s not so simple. This may be why next, I want to do a film with a plot, to let me have some time to think about how to confront this issue. There would be actors in such a film.

But there aren’t actors in a documentary. I still need some time to think about the relation between the lens and people. While having not completely figured this out, I am already

Taiwan and Hong Kong

SC: Do you see similar circumstances between Taiwan and China? We also wanted to ask if you have seen documentary films regarding Taiwanese social movements and if you have any views on them.

Taiwan seems to have many people that film social movements, but there are many documentary films about the Umbrella Movement, while there are far fewer films about the Sunflower Movement.

NL: I am not too familiar with Taiwan’s filmmaking environment, although I have seen The Sun Is Not Far. That was a long time ago though, so I don’t remember it too clearly.

Regarding comparisons between Taiwan and Hong Kong, that’s a tough question. It’s one for academia, I think. I did pay attention during the movement, but I can’t understand the entire situation. We felt quite moved when everyone charged into the Legislative Yuan, everyone was watching livestreams or news reports.

A lot of Hong Kong people were saying that you were all quite brave. And there was talk about whether something similar could occur in Hong Kong. Two months later, a group of social movement participants tried to charge into the Legislative Council to oppose development in the New Territories. They wanted to charge into the Legislative Council.

The LegCo meets every Friday. They were successful in charging inside then and I was there filming. Everyone was wondering if it would become as successful as the Sunflower Movement in establishing an occupation.

But not many people participated and police violence was heavy. For some weeks after, people tried to rally people to charge the LegCo, but they were not successful. It was a group called the Oppose the New Territories Development Association.

That was in June and July. Then in September, the Umbrella Movement took place. And I thought that it was quite amazing, seeing as while we may not have been successful charging into the Legislative Council, we charged the streets instead. So I think the Sunflower Movement may have been a very good example for us in terms of what the people could do.

This notion may have come from there. Benny Tai and others also proposed Occupy Central and things like that. To occupy a government building using the strength of young people, a key part of the state apparatus, and to force it to make changes, for me, that concept didn’t come from Benny Tai or Occupy Central, but from the Sunflower Movement.

During the Umbrella Movement I was young, I was 18 or 19. I didn’t understand many things. But in these past few years, I see many friends studying history, After the failure of the Umbrella Movement, many people felt disoriented, they all wanted to do some things to change themselves. Many pursued further education. To read things to do with democracy theory or democratization, in many cases drawn from Taiwan.

That wasn’t in official courses usually, just reading things on your own. Hong Kong university students also like to invite scholars from Taiwan to Hong Kong to discuss personal identification or how to establish an independent country.

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

In reading through Taiwanese history, it feels to me as though what happened in Taiwan in the 1970s or 1980s, the White Terror, may be what will take place afterwards in Hong Kong. That generation of Taiwanese also confronted many difficulties, with a need to flee the police, during the martial law period.

I liked to read these stories, I felt it was quite moving. I wondered, will Hong Kong people one day have the bravery to do things like this? The Hong Kong government currently may not be as bad as the KMT, since it hasn’t killed anyone yet, but it may deteriorate to this situation. Twenty or thirty years from now, Hong Kong could become like during the White Terror.

It was also reading how, up to from one hundred years ago, Taiwanese were colonized, but gradually found their own sense of self-identification. To protest for the sake of their own country, nation, and people. As a result, at present, there seems to be a better situation. There’s democracy, there’s a legislature, there’s free press, and freedom of expression, This may be a good aim. But only after how many years can it become like this?

A few weeks ago, Initium Media published a report. I’m not sure if it’s true or not, but it was that nearly 70% of Taiwanese were willing to fight against China to defend their country in the event of a Chinese invasion. This may not be the case in Hong Kong. If Hong Kong were to fight with China, many people would run immediately.

So I think Taiwan is a good example on many of these issues. I know that Taiwan has many social issues, but as an outsider, I only see Taiwan’s good side. I think this may be so more generally for Hong Kong.

The Current Filmmaking Situation in Hong Kong and Comparisons to Taiwan

SC: You have mentioned that you have no ruled out fictional films and that you hope to try this in the future, what I want to ask is, do you worry that your current work will affect whether you are able to make films in the future? Have other filmmakers in Hong Kong been influenced by the political circumstances of Hong Kong? Does this affect freedom of expression?

NL: I didn’t get to discussing theaters earlier. We weren’t able to find theaters willing to show the film. It’s a pity. Because I don’t focus on his background, or his political views, I focus on him as an individual.

There are few screenings in Hong Kong. Even if we look to rent ourselves, theaters decide that they won’t accept this money.

In theory, there’s no law in Hong Kong saying that you can’t do this. I am skeptical whether the higher-ups of theater companies would pay attention to their theaters are showing small films that nobody has ever heard of. I believe that it is primarily middle-level individuals who are afraid that their bosses may get upset who self-censor, when their bosses may simply never notice. I believe that this is the present. Where the government hasn’t directly carried out any form of action, people carry it out themselves.

The last British colonial governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten said one that he didn’t fear that Hong Kong’s freedoms would be taken away, but that Hong Kong’s freedoms would, in the hands of small group of people, gradually deteriorate. It’s gradually become like this. It’s quite frustrating.

In making this film, I wanted to see how this story could move the largest amount of people, as far as possible. Commercial film theaters are a very good venue for this. But there’s no way to do this currently.

As for the future, I haven’t thought too much about the future. Because I am working on other projects, which are pretty good opportunities to learn. In the future, if I want to make a very commercial film, I wouldn’t be interested in that. My next project is smaller-scale, so I’m not too worried. But afterwards, I am unsure. A few years later, I don’t know, it’s also hard to say what may happen in China.

I haven’t thought too much about this, but I believe that Lost in the Fumes has given me many new opportunities, including allowing me to do some larger projects, or to get to know some very talented people and to learn from them. Some people warn me to be careful, to not say so much, or to not film this kind of film, but I don’t think too much about it. If I had start filming love stories, for example, many people produce love stories, and it may not be so good.

The things that I have now come from my subject material, it is hard to say where I have lost opportunities because of my work.

But if you ask me in a few years, when I have been rejected by many film companies, maybe I’ll give you a different answer. [Laughs] But this is what I would have to say right now on May 10th, 2018.

SC: I don’t know if you know about Taiwan’s film situation, but many film industry people–much more with fictional movies and their actors and directors–because Taiwan’s market has become smaller, they will go to China.

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

NL: This is also the case with Hong Kong.

SC: But many Taiwanese actors or directors are forced or force themselves to say that they are Chinese.

NL: I’ve also heard of this.

SC: I would like to know if Hong Kong has many such circumstances. Or whether this is something that people in the Hong Kong film industry are concerned about.

NL: I think there is. However, many talented directors or actors from Hong Kong already went to China. And I think that many did this on their own. I don’t think they’ve taken to cracking down as much.

Some Hong Kong actors and directors are unable to work in China now, such as Denise Ho, Anthony Wong Yiu Ming, Chapman To, and other very talented individuals, for being very outspoken. China has decided that these talented actors or singers can’t work there.

I don’t know if they will inspect all of the actors and directors that go to work in China in the same way in the immediate future. So far it may be the ones who are the most outspoken. Yet they also become popular in Hong Kong for being so outspoken and people hire them to film commercials. If they film those, maybe they don’t need to go to China.

But right now it’s not every movie star or television star in Hong Kong that goes to China. Going to China can be frustrating too. However, I think the circumstances you are talking about may arrive in Hong Kong one day.

SC: That is quite interesting, because it feels more pessimistic in Hong Kong politically, because Chinese pressure is harsher and Taiwan has more political freedoms.

But in the film industry, Taiwan’s film industry might actually have more Chinese pressure than Hong Kong at present. This is quite an interesting comparison. Every Taiwanese movie which hopes to enter the mainland market must pass through this currently.

NL: I’m not sure why either. What you say is quite interesting. It could be that Hong Kong films entered into Taiwan earlier, as well as into China. Many Hong Kong actors left to make films in China very early on. They are already very well known in China and probably don’t fear too much for Hong Kong films being crowded out by China too much.

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

Photo credit: Lost in the Fumes/Facebook

SC: So it may be a product of that Hong Kong people may have had earlier contact with the Chinese market. I see.

What are your next projects? Where do you hope for your film to be shown next?

NL: I’m working on a short script. Outside of politics or documentaries, I’m not particularly afraid of political repression or anything else, but I’m working on new material.

SC: Do you plan on showing Lost in the Fumes at other locations?

NL: I’ve also applied to other film festivals, but have not had news yet. We will continue to screen in Hong Kong as well, in independent cinemas or arthouse theaters.

Reception of the Film

SC: What kind of responses have there been from people who have seen your responses in Hong Kong? Because, as mentioned by you in past interviews, there may be those who think that you are glorifying Edward Leung, while you have stated that you are actually filming some of his negative sides. You’ve also mentioned that many theaters refuse to show this film.

On the other hand, what have responses been in Taiwan and the international world?

NL: I quite like to hear what the audience has to say. But, seeing as I have origins in comparative literature, I quite believe a theoretical point of view that comparative literature students learn in their first year, which is Barthes’ death of the author. I won’t say towards any viewer of the film whether their views are correct, are incorrect, or what my views are.

So I can understand why they would view me as glorifying Edward Leung, or won’t say that this is not the right interpretation, except to just say that this was not my aim. But I accept and respect this point of view. When you spend time to analyze or reflect on my film, I already feel satisfied.

After my film came out, there were many responses, some positive and some negative. Regarding comments on it technically, or regarding editing, I feel quite grateful. But what leads me to feel more moved is that–well, it’s very cheesy to say, but because audience members felt moved, I also felt moved. Because I worked on the movie for a long time. One or two years. I spent a long time with Edward Leung and working on the film.

However, unlike me, when an audience member sees the film, it’s their first time seeing it. For them to experience what I experienced for a year, or to understand the message I want to give them, this is very encouraging for me, particularly as I am working on other things which give me a lot of pressure in these past few months. So I think that this movie can connect people.

Edward Leung is a very particular person in Hong Kong. Few people will, like him, be condemned to ten years in prison, threaten the government like that, or stand for the cause of Hong Kong independence.

In the course of Edward Leung’s indecision, he had a dream, and in the process of pursuing this, he came to understand that the world is very dark, and that dream was shattered. Or perhaps we can see it as him gradually understanding the realities of society, that he came to gradually discover that society is very dark, or that human fate is very dark. How does he react to that?

That’s what I was thinking. I think that this would be my response to those who criticize it on the basis of political views. You don’t have to agree with Edward Leung’s views, but you can still experience this. I think that an audience member with no relation to Edward Leung, who may hate him very much, may be able to see that they are similar to Edward Leung in some ways, that we’re all people with ideals. To create this kind of connection would be very satisfying to me.

Many audience members have said to me that after watching this film, they felt very moved, and were thinking about fate, dreams, and ideals, and these kinds of things. I don’t expect that audience members will have any agreement, say, with Hong Kong independence or localism after watching the film, but many audience members said to me that they felt they understood something more about human nature after watching the film.

Photo credit: Ming-Siou Tsai

Photo credit: Ming-Siou Tsai

SC: Something I am curious about is why you would want to describe this from the point of view of a regular person. Because usually in addressing these kind of highly charged political issues, such as Hong Kong independence or social movements, whether in terms of a fictional movie or a documentary film, people usually first look into things from the standpoint of the “event.” But why did you decide to proceed from the point of view of an individual person? Did this come from your interest in telling stories, or your studies in literature?

NL: I think it might be related. Like I said earlier, a moment in which I felt a great deal of affinity was when he called me and said that, “I feel the way like you talked about.” I think that because Edward Leung could move me, he could move my audience members.

My instincts told me that he probably would not say this to other journalists, or that in other circumstances, he might not say this. That if I don’t focus on this, nobody would know about this. It made me feel it was worth recording.

On another point, if I talked about Hong Kong independence or other political matters, my own position would necessarily become part of my film. But when you take such a small, limited approach, you can only move part of the audience. That part of the audience may have already supported Hong Kong independence, or had a deep understanding of politics, and it may make them happy to see that in a film, but I believe that that is less meaningful.

I believe that those with different political views, who may not like Edward Leung, only if they are willing to watch the film, then then this is more descriptive Edward Leung–not only in terms of his views–and that this adds to the ability of the film to resonate. If I filmed a movie very focused on his political ideals, then in Taiwan or the international world, they might not know Hong Kong’s political background very well and might not be able to understand this film. But filming him play the guitar or talking about his dreams, or discussing his dreams, can connect with ordinary people.

I also think that in terms of my work, I began from a very political, topic-based approach as a journalist. My first short film was about the Umbrella Movement. I gradually started to develop interest in an people and how they related to individual issues. My previous film also begins from the point of view of an individual then towards Hong Kong’s larger events, regarding two young students confronting the changing circumstances of social movements. Then by the time of Lost in the Fumes, I was more focused on individuals, only looking at an individual, examining his interiority, and how he confronts the world.

Many people in Hong Kong claim that this is a deliberate means of depoliticizing the film. I can understand why they would say this. When editing, I also deliberately removed when Edward discusses Hong Kong’s political circumstances. I think that this is unrelated to the focus of my film.

But why does Edward Leung have to confront these circumstances? Why is he so passionate? Ultimately it is because of politics. Even if in Hong Kong, I watch romance movies, or crime movies, behind that is politics. Society is politics.

Conclusion

SC: In closing, what would you say to not only Taiwanese readers, but international readers?

NL: I know that Edward Leung is lesser known outside of Hong Kong, such as how Joshua Wong is known. I hope that people can, through this movie, come to know what is taking place in Hong Kong.

Photo credit: Ming-Siou Tsai

Photo credit: Ming-Siou Tsai

Hong Kong is a wealthy city from outside appearances, but there are fewer people who actually live in Hong Kong. However, Hong Kong’s young people are not the glamorous people you see in television dramas or in movies, but regular people pursuing their ideals and dreams. With the disruption of their ideals and dreams, this is the environment in which they are trying to understand their future.

I hope my movie can represent 2018 and the stories of young people in contemporary Hong Kong. Much news reporting on Hong Kong is out of touch with events and is not truly very representative of Hong Kong. Indeed, I very much like Hong Kong films from the 1970s and 1980s, such an an Autumn’s Tale or Comrades: A Love Story, which are not directly about politics and may be very commercial, but engage with historical changes. We may need this kind of movie in the mainstream to discuss Hong Kong in 2018, as well.

Symin Chan (詹斯閔) is a major in philosophy in NTU, working hard to be a writer. She hopes to reveal the real images of Taiwan.

Brian Hioe (丘琦欣) was one of the founding editors of New Bloom. He is a freelance writer on social movements and politics, and occasional translator.