by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Phil Whitehouse/WikiCommons/CC

AS WITH OTHER recent national referendums in Catalonia and Iraqi Kurdistan, are there any other lessons which can be derived from the referendum on gay marriage that was recently held in Australia for referendum reform in Taiwan? 12.7 million Australians participated in the referendum, some 79.5% of Australians eligible to vote, and a clear majority of 61.6% of Australians voted in favor of legalizing gay marriage. The referendum was non-official, but organized by the government. Australia previously had civil partnerships, but the vote was on realizing full marriage equality.

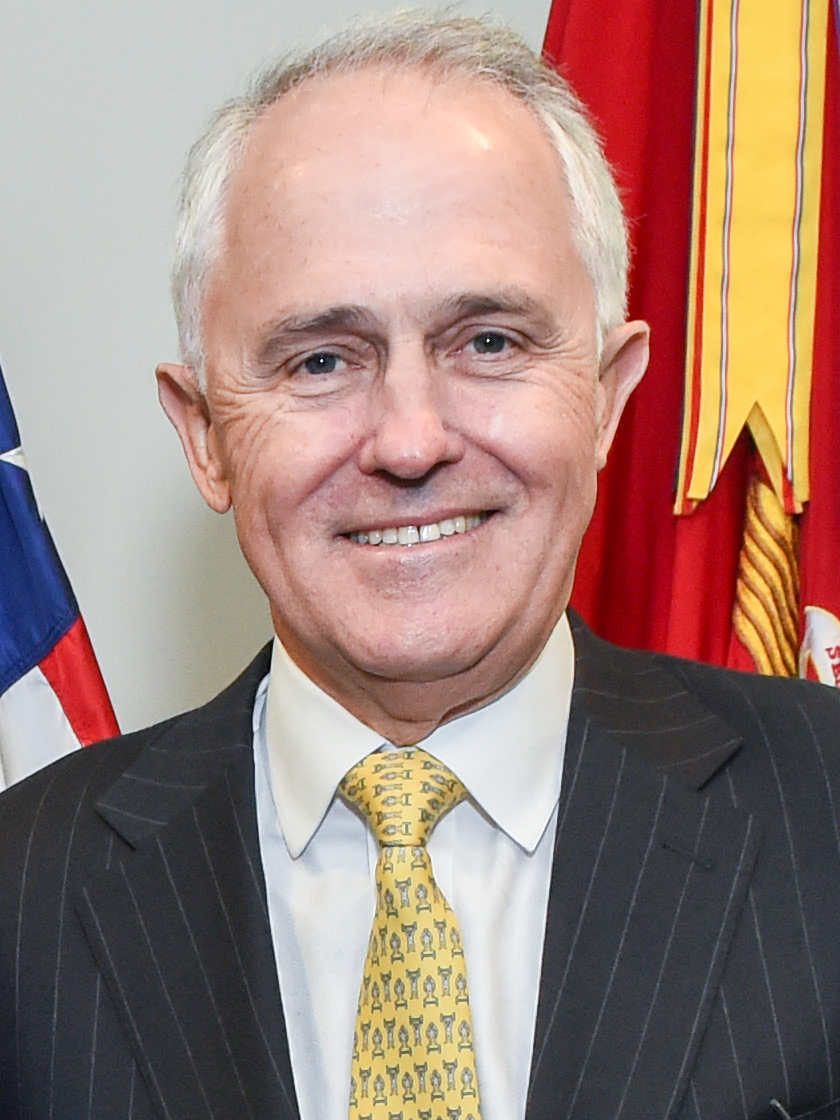

First, for Taiwanese who seek to juxtapose Australia as planning on speedily taking action on the issue following the referendum to currently tarrying by government officials reluctant to legalize gay marriage despite the historic ruling by the Council of Grand Justices that same-sex marriage must be legalized within two years in May, this is not the case. But the referendum does offer comparisons to Taiwan nonetheless in this regard. Namely, much as Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-Wen is hampered from legalizing gay marriage by the Christian wing of her party, the referendum on gay marriage was pushed for by current Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull as a delaying tactic to placate the far-right wing of his party.

Malcolm Turnbull. Photo credit: Department of Defense

Malcolm Turnbull. Photo credit: Department of Defense

As such, the referendum in Australia was actually criticized by some LGBTQ groups as a waste of resources and an attempt to evade the issue by Turnbull, despite the fact that it was clear beforehand that gay marriage enjoys majority support in Australia. But this raises the possibility of referendum being used in Taiwan by the government as a delaying tactic, as a way to claim the need to seek consensus on issues which have already been settled.

One saw similarly with the Greek referendum in 2015 on the issue of bailouts from the European Union, in which the left-wing Syriza party called for a referendum on the issues that it had more or less been elected to power on the basis of because of a hesitancy to follow through with this platform. This was an early sign of Syriza’s eventual accommodation to conservative political forces. One can easily imagine referendum in Taiwan being used as a delaying tactic by the DPP or another government to avoid confronting key issues, rather than as a means of settling longstanding issues such as Taiwanese independence or nuclear power in Taiwan. Indeed, probably with such aims, we do well to remember a referendum on the issue of same-sex marriage was actually called for by opponents of gay marriage in Taiwan, who likely hoped to at least delay the legalizing of gay marriage or that there would not be a consensus on the issue.

It remains an open question whether any hypothetical referendum in Taiwan on long-standing issues such as gay marriage, nuclear power, or gay marriage would attract international attention. This can be observed in the international attention which the Catalan referendum received but the lack of international attention which the referendum in Iraqi Kurdistan received by comparison, likely because the former took place in a western context and the latter in a non-western context.

But with the international attention that the referendum on gay marriage in Australia has received, this also shows the power of referendums, even legally non-binding ones, if they have enough votes from society that they can clearly illustrate the views of a majority of society. This might be difficult in Taiwan, seeing as it is difficult for any referendum not organized by the government to include the majority of society, and despite being legally non-binding, the Australian referendum was organized by the government. However, this shows the possible benefits of referendum nonetheless.

Nevertheless, it might still be an uphill struggle for an independence referendum in Taiwan to succeed nonetheless. The vast majority of independence referendums are not successful, even if this has become commonly established as a tactic for nation-states seeking independence or recognition. Successful examples in which a nation-state was able to achieve independence after holding a referendum in the past several decades were probably successful moreso due to geopolitical circumstances, such as with the collapse of the Soviet Union or the breakup of Yugoslavia, or the direct aid of international bodies such as the United Nations in holding a referendum and maintaining its legitimacy. In such cases, referendum may not have been the driver for successful independence, seeing as referendum is sometimes thought of as a way to permanently settle the issue of independence in Taiwan, but merely something which contributed to it.