by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Huang Rong-zan

Why Demand Transitional Justice?

WHY THE NEED for transitional justice in Taiwan, anyway? Is it not that Taiwan is already “post-authoritarian”? Certainly, that would be what much of western commentary regarding Taiwan assumes, that Taiwan is unequivocally “post-authoritarian”. But the paradoxes of so-called Taiwanese democracy are many and the crimes of the authoritarian period have not been settled.

Taiwan is a country where, after all, the standing president, Ma Ying-Jeou, is an individual who actually opposed the opening up of direct elections for choosing the president of the nation during democratization in the 1990s. During past elections in January, no less than the former head of the Government Information Office responsible for government censorship during the martial law period, James Soong, would run as a presidential candidate. Indeed, in the case of notorious “White Wolf” Chang An-Lo, we even saw in elections in January 2016 actual murderers responsible for killing dissidents at the behest of the KMT running for legislature.

How, then, is Taiwan “post-authoritarian”? It actually seems at times that the claim that Taiwan is “post-authoritarian” is a way to smooth over the crimes of the authoritarian period and pretend that outstanding issues of injustice have already been resolved. So, then, does the claim that Taiwan is already “post-authoritarian” become a convenient excuse for the guilty parties of the authoritarian period to continue to participate in politics.

If “transitional justice” is the attempt to resolve past crimes of an authoritarian period during the transition from authoritarian period to a post-authoritarian period, the idea would be that Taiwan is not truly post-authoritarian. Rather, the suggestion would be that Taiwan is still in its process of political transition and not out of that transition yet.

Not Exactly Out of Political Transition?

FOLLOWING THE terms dictated by democratization theory, various attempts have been made to point out a specific moment in history after which Taiwan became “post-authoritarian” and achieved a stable, functioning democracy. Various historical points which have been offered up as historical moment in which Taiwan transitioned to a full democracy. This includes the first DPP presidency in which Chen Shui-Bian assumed presidency as the first non-KMT president and then the transition of power from DPP back to KMT with the defeat of the DPP in 2008 and 2012 presidential elections.

Such peaceful transitions of power were seen as indicating that Taiwan had fulfilled the criteria for a democracy, having thrown weight of its authoritarian past. Now, the recent victory of Tsai Ing-Wen and the transition of presidential power from KMT back to DPP is asserted as being yet another benchmark for Taiwanese democracy, indicating something about the completion of Taiwanese democracy.

But how many transitions of power are needed exactly before Taiwan is to have achieved this longed for Platonic ideal, “post-authoritarian democracy”? To begin with, if it only were so easy that one could point to a specific moment in time and decide everything before it to have been “authoritarian” and everything after it to be “post-authoritarian.” Moreover, using transitions in presidency as indicator of a transition in political power privileges the office of the presidency above all other forms of political office.

After all, there was never any point at which the DPP controlled the legislature up until 2016 legislative elections. It also remains that the KMT has unofficial strongholds within branches of government, from the central government to local schools, by way of informal, personalist networks based on personal relation as well as interest-based networks founded upon the ability of the KMT to reward supporters.

We also find that political transitions in power are not as stable as they appear retrospectively. Tensions have been raised recently by the possibility of sudden shifts in foreign policy Ma may undertake in the last months of his term, as we see in his sudden Itu Aba island visit. Ma has openly declared that he refuses to be a “caretaker” up until the time Tsai Ing-Wen takes office, seeing himself as an active president who still has several months remaining in his term. This has led some to even call for Ma being removed from office through impeachment procedures to ensure a smooth transition to power to Tsai, though among those who call for Ma’s impeachment, there is also an element of hoping that this would be political retribution against Ma.

What Would Transitional Justice in Taiwan Mean?

WHAT WOULD transitional justice in Taiwan mean, then? Transitional justice is a term which has been used in other post-authoritarian contexts in which large-scale violations of human rights took place, such as in cases of ethnic cleansing. Transitional justice has been used as a guiding concept for justice proceedings in post-Nazi Germany and post-authoritarian Argentina, for example.

Those who advocate transitional justice in Taiwan likely do so in part to raise Taiwan’s profile as a context in which large-scale violations of human rights took place. This would be by placing Taiwan alongside more famous nations as Germany or Argentina in which past crimes during an authoritarian period were addressed through the framework of transitional justice. The past crimes of the KMT during 38 years of martial law in Taiwan, the longest in world history, in need of redress would be the 228 Massacre that occurred after the KMT came to Taiwan, the mass killing of political dissidents during the White Terror, which left 20,000 to 30,000 dead, and other incidents of the KMT’s persecution, torture, and murder of dissidents through use of secret police.

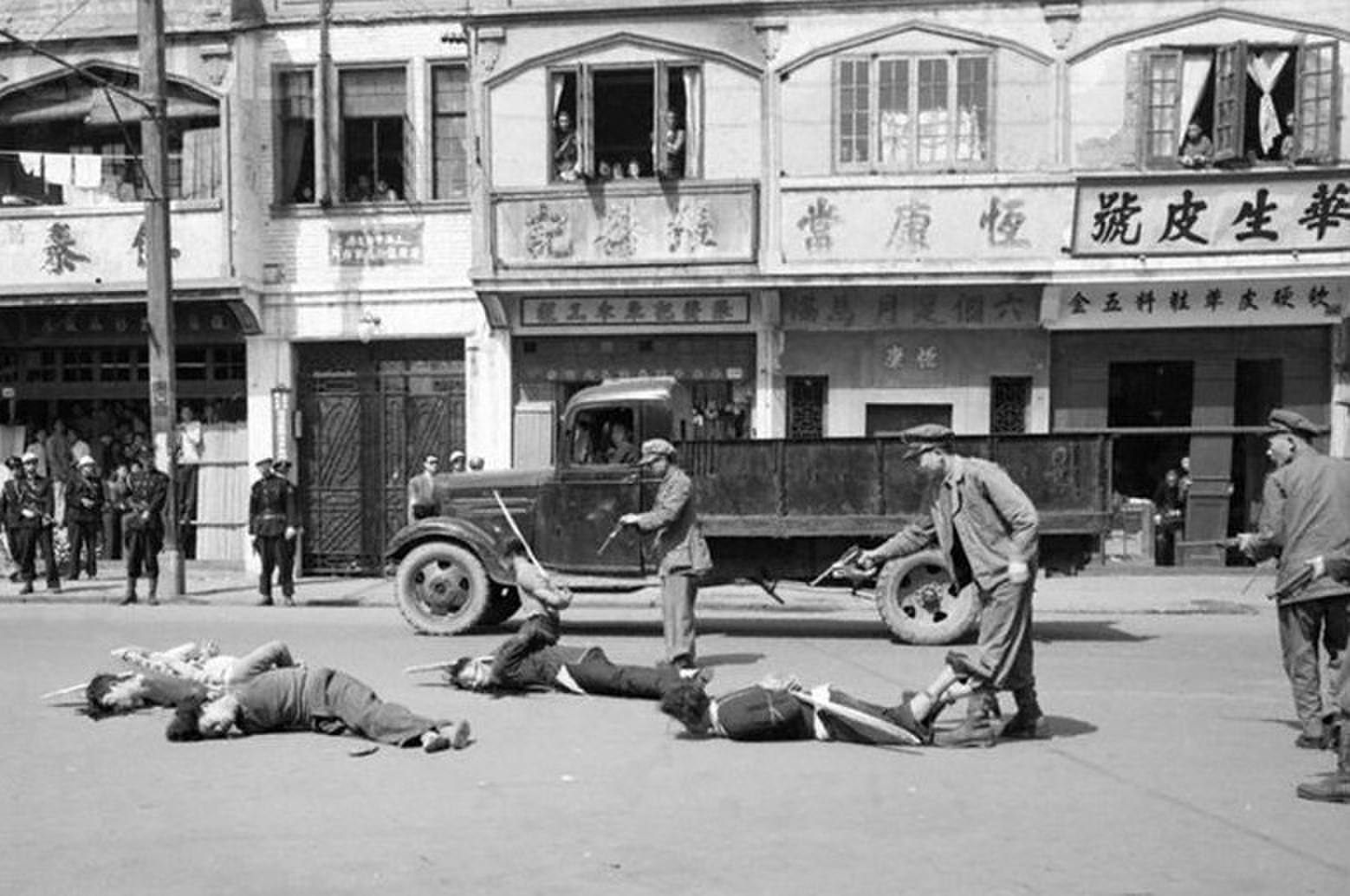

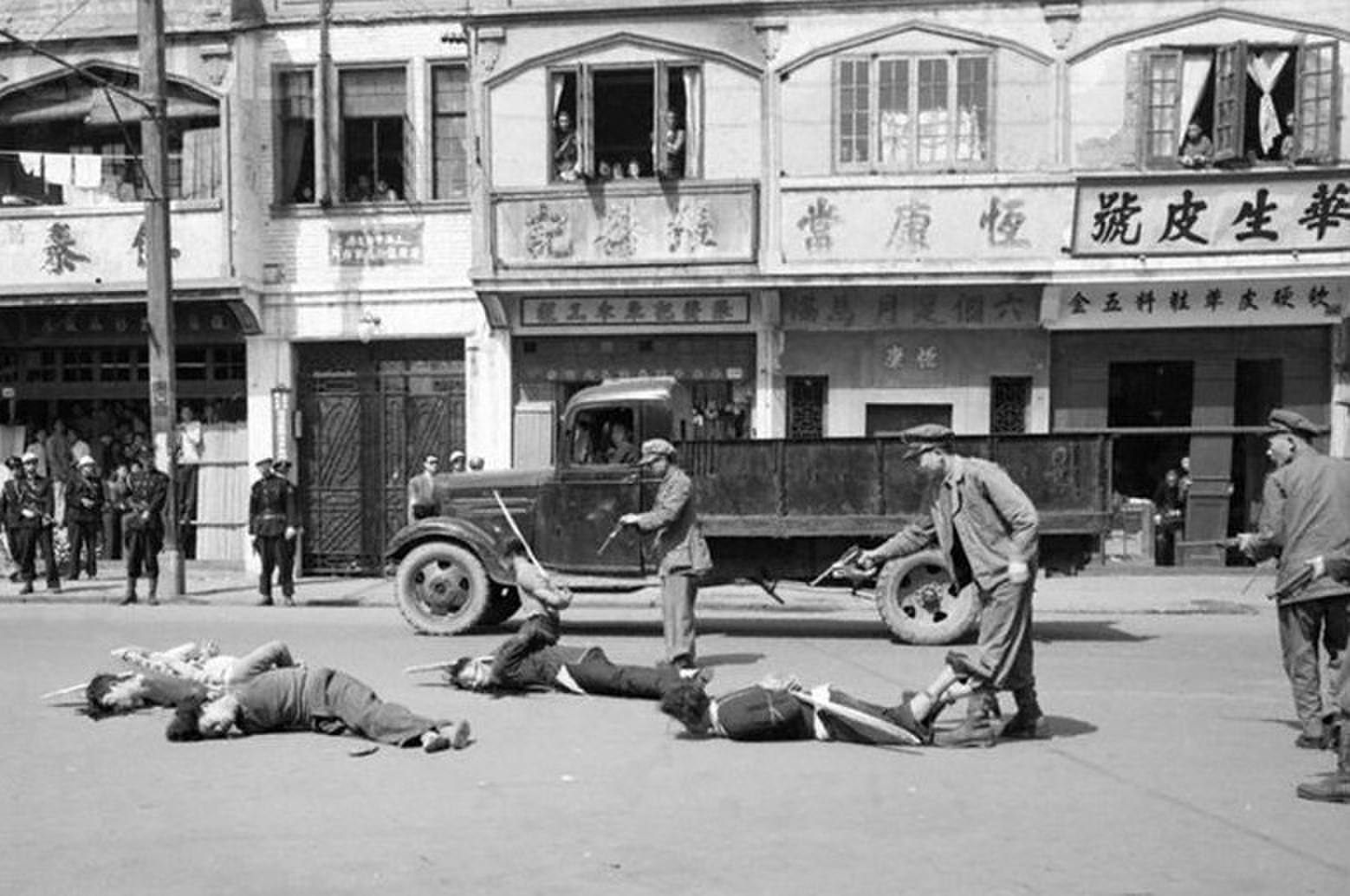

Likely because of its resemblance to the woodcut memorializing 228, “The Terrible Inspection” by Huang Rong-zan, the following image of killings likely in Shanghai was widely circulated as a picture of 228 after being featured in a documentary by SET TV

Likely because of its resemblance to the woodcut memorializing 228, “The Terrible Inspection” by Huang Rong-zan, the following image of killings likely in Shanghai was widely circulated as a picture of 228 after being featured in a documentary by SET TV

In many ways, it remains to be worked out in more concrete terms what transitional justice would mean in Taiwan. As it is a characteristic of transitional justice proceedings to call for truth tribunals and the payment of reparations, this would likely be a part of what transitional justice would entail in Taiwan.

In many ways, it remains to be worked out in more concrete terms what transitional justice would mean in Taiwan. As it is a characteristic of transitional justice proceedings to call for truth tribunals and the payment of reparations, this would likely be a part of what transitional justice would entail in Taiwan.

Certainly, there have already been reparations paid to 228 victims, but part of the continued call for transitional justice in Taiwan is because there still remains much which is opaque about the past crimes of the KMT during the martial law period. To use two famous examples, no explanation has yet emerged for the death of dissidents as Chen Wen-chen, for example, whose bruised and beaten corpse was discovered on the campus of National Taiwan University. Or in regards to the unsolved killing of Lin Yi-Hsiung’s mother and two daughters in the Lin family home when the Lin family home was under 24/7 surveillance by police at that time.

Of course, in these cases, the secret police of the Taiwan Garrison Command is the obvious culprit. But no official explanation has been given. There are many other, less publicized cases in which there is even less known. As we see with the plethora of KMT politicians culpable of past misdeeds that are still running around, it remains that few of the culprits of past crimes committed in Taiwan have not been held to account and many remain politically active.

Potential Roadblocks for Transitional Justice?

NEW THIRD parties that emerged from post-Sunflower movement civil society have been among those calling most proactively asserting the need for transitional justice in Taiwan, in particular, the New Power Party which now holds five seats in legislature. Yet there are roadblocks which would probably impede future calls for transitional justice.

In light of that much of the international world and, indeed, much of Taiwanese society does truly believe Taiwan to be post-authoritarian and democratic, trying to hold to task politically active KMT politicians who were responsible for crimes during the authoritarian period may be seen as political retribution.

Attempting to bring about legal proceedings against KMT politicians, for example, would be seen as political revenge against the KMT by the DPP or pan-Green political actors. This would be seen as continuing the cycle of hatred between political parties in Taiwan by which, for example, the KMT could jail former DPP president Chen Shui-Bian on charges of corruption but the DPP would do no different than the KMT in seeking revenge upon the KMT once in office.

Actually, this may be a future source of division between new, third parties and the DPP, seeing as new parties may push for transitional justice quite assertively but, wary of the accusation that it just desires political revenge against the KMT, the DPP may take a more cautious line. We see this already in the divided reactions regarding Chiang Kai-Shek and Sun Yat-Sen statues and portraits across Taiwan.

In this way, Taiwan is caught between the uneven overlap of its present and the authoritarian past that it has not quite overcome. How, then, will the crimes of the authoritarian period find resolution? What will it take for Taiwan to truly transition to a post-authoritarian democracy? This is what remains to be worked out. And ultimately, it may take more than electoral politics for there to be any satisfactory solution.

Likely because of its resemblance to the woodcut memorializing 228, “The Terrible Inspection” by Huang Rong-zan, the following image of killings likely in Shanghai was widely circulated as a picture of 228 after being featured in a documentary by SET TV

Likely because of its resemblance to the woodcut memorializing 228, “The Terrible Inspection” by Huang Rong-zan, the following image of killings likely in Shanghai was widely circulated as a picture of 228 after being featured in a documentary by SET TV