Comparing and Contrasting the Two Movements

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Brian Hioe

This is part two of a two part article about the recent occupation of the Ministry of Education which ended two days ago. Part one focuses upon the responses of politicians and political forces to the Ministry of Education and part two will serve as a compare and contrast between this year’s occupation and last year’s Sunflower Movement.

LOOKING BACK we can maybe say that in some way that the textbook protests which have rocked Taiwan in the past week occurred in the shadow of last year’s Sunflower Movement. Though I think it true to say that the movement eventually developed its own identity as distinct from the Sunflower Movement, this was true from the beginning, where the original plan to surround the Ministry of Education which was publicly announced by activists several months in advance was called a “Second Sunflower Movement.”

With the end of the occupation, if we are to look back on the movement, was it really a second Sunflower Movement? Certainly, it is true that the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement was never as large, and the political crisis it expressed was not as all-encompassing of society. But we might venture a compare and contrast of the two movements.

What Was the Sunflower Movement About and What Was the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement About?

THERE IS IN some sense truth to the claim the Sunflower Movement and Anti-Textbook Revision Movement were about the same thing, namely, the KMT government’s continued attempts to bring Taiwan closer to China in disregard of the views of the Taiwanese people. Where both issues concerned the undemocratic and untransparent means by which the KMT pushed through policies aimed at bringing Taiwan closer to China, this is where both movements were referred to as movement against “black box” policies. With the Sunflower Movement, this was the “black box” trade agreement of the CSSTA signed with China and with the Anti-Textbook Revision movement, this was with the planned textbook revisions which would teach a Sinocentric view of history to Taiwanese.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

However, if last year’s “black box” CSSTA directly concerned the relation to China—as well Taiwan’s incomplete democratic transition with the lingering authoritarianism of the KMT—the textbook issue this year did not have this external factor of the relation to China. At stake was once again the question of identity, in regards to that Taiwanese do not identify as part of China, but there was no direct connection to China in regards to the issue that set off the movement. The CSSTA involved the KMT, but that also was a trade bill signed directly for China. In comparison, the textbook issue was a purely domestic one.

Arguably, the CSSTA trade agreement or textbook issues were largely hotbed issues for the Taiwanese public because of this shared, central question of the KMT’s continued attempts to forcibly bring Taiwan closer to China. There are many such issues which could set off controversy, but it just so happened that it was these two that did. But, of course, it was that the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement was set off by the suicide of Lin Kuanhua, leading to an explosion of grief and outrage about what was a longer standing issue.

Was the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement Attempting to Mimic the Sunflower Movement in Terms of Organization?

WHAT THE Anti-Textbook Revision Movement shared, most obviously, with the Sunflower Movement was the preferred tactic of occupation. Actually, that the past week’s occupation came out of the longer Anti-Textbook Revision campaign had led to some divides between the largely college age participants of the Sunflower Movement and the high school student participants of the Anti-Textbook Revision campaign. Participants of the Sunflower Movement were critical of what they saw as the fixation of high school students on recreating the conditions of the Sunflower Movement when they themselves did not see the movement as wholly successful on the basis of the tactics adopted. So, then, were original Sunflower Movement participants dismissive of the aim of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement to become a “Second Sunflower Movement.”

Indeed, Ministry of Education occupiers only ever occupied the courtyard of the Ministry of Education and never managed to occupy the building. But before the successful occupation of the Ministry of Education courtyard which occurred on July 30th as a spontaneous outburst of outrage over the death of Lin Kuanhua, there were several attempts at building occupation, including the one which took place on July 23rd in which occupiers got into the Ministry of Education building and made it as far as the office of the Minister of Education, Lin being the first of those who got inside the office to be arrested.

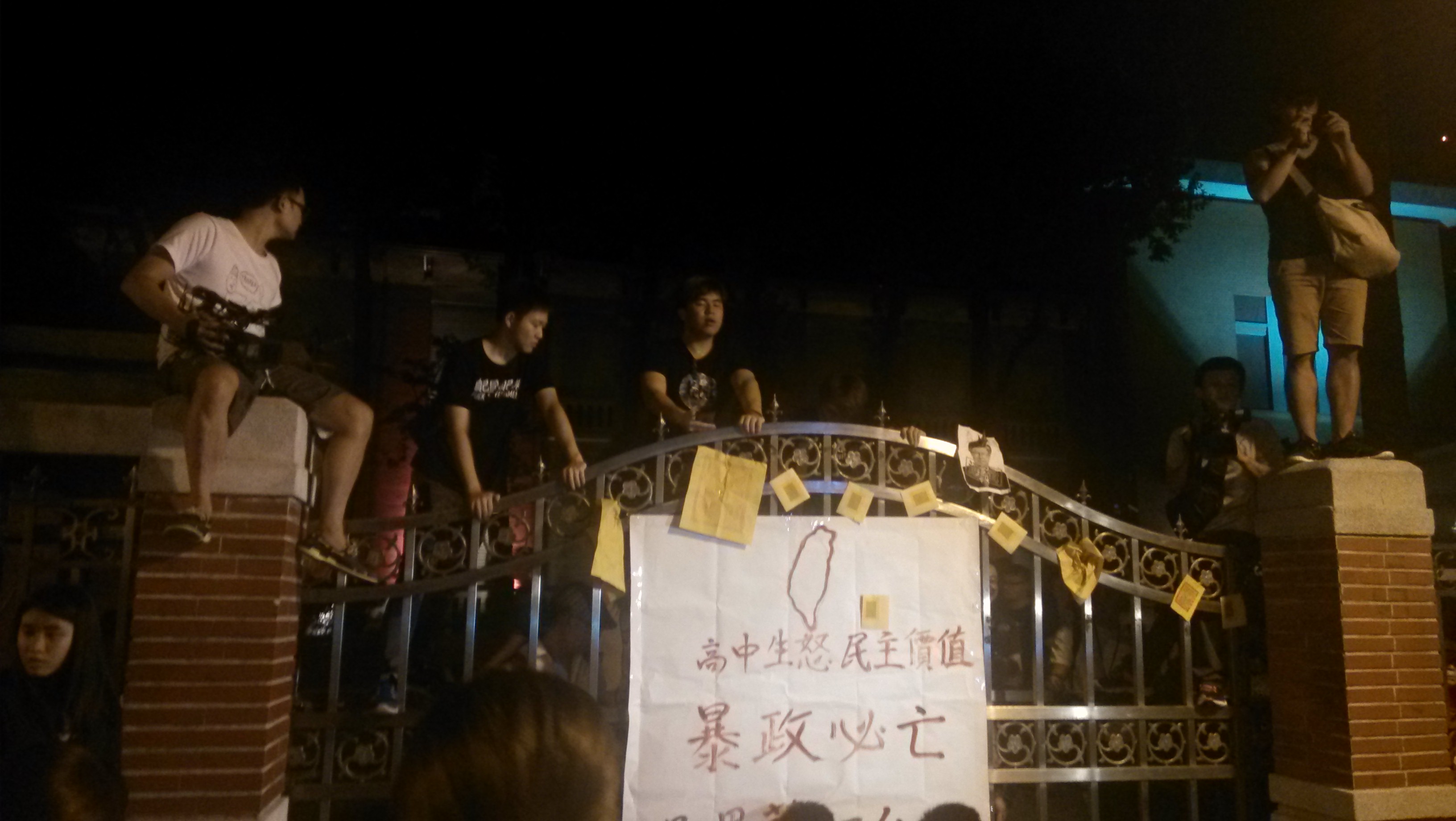

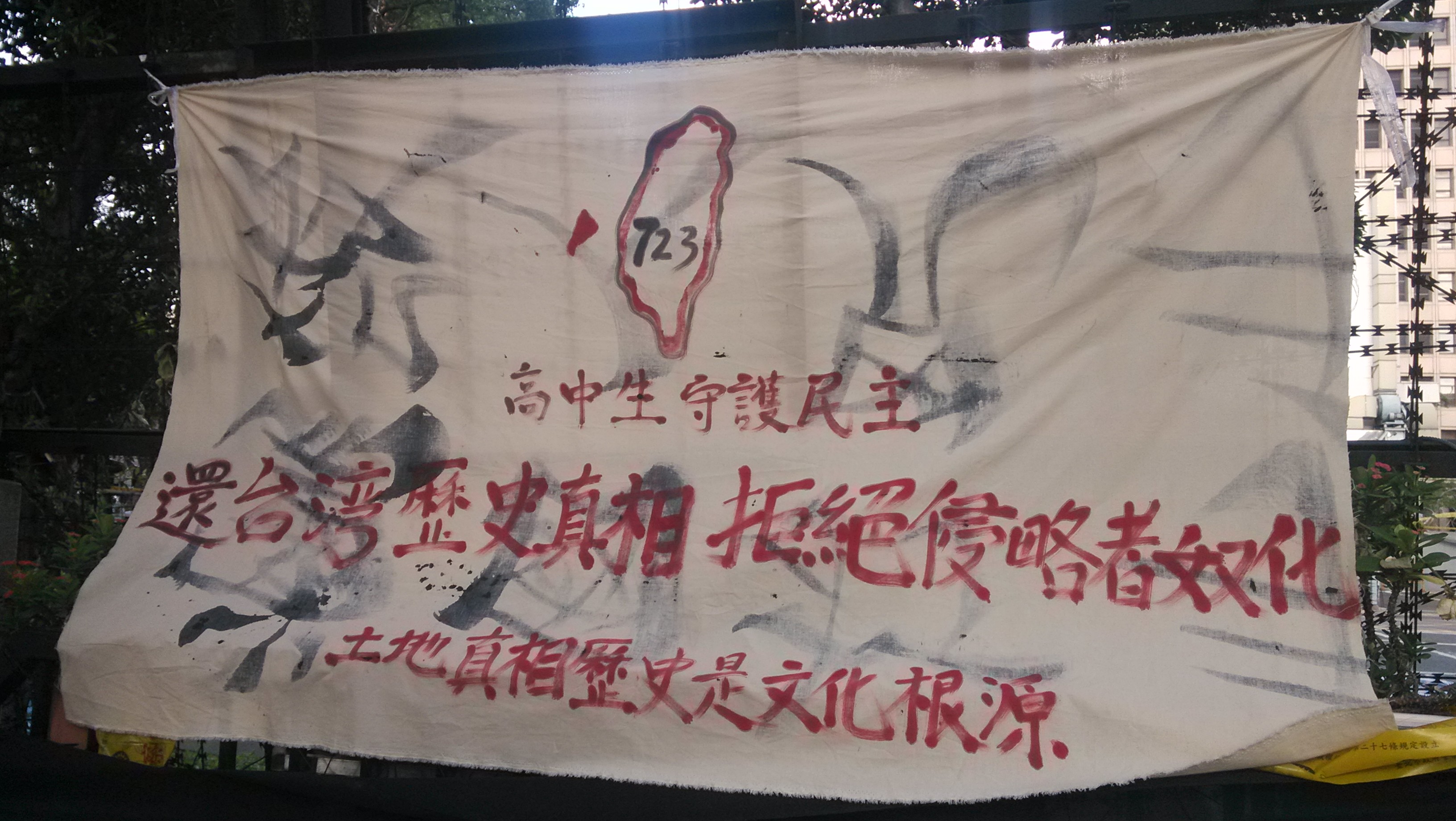

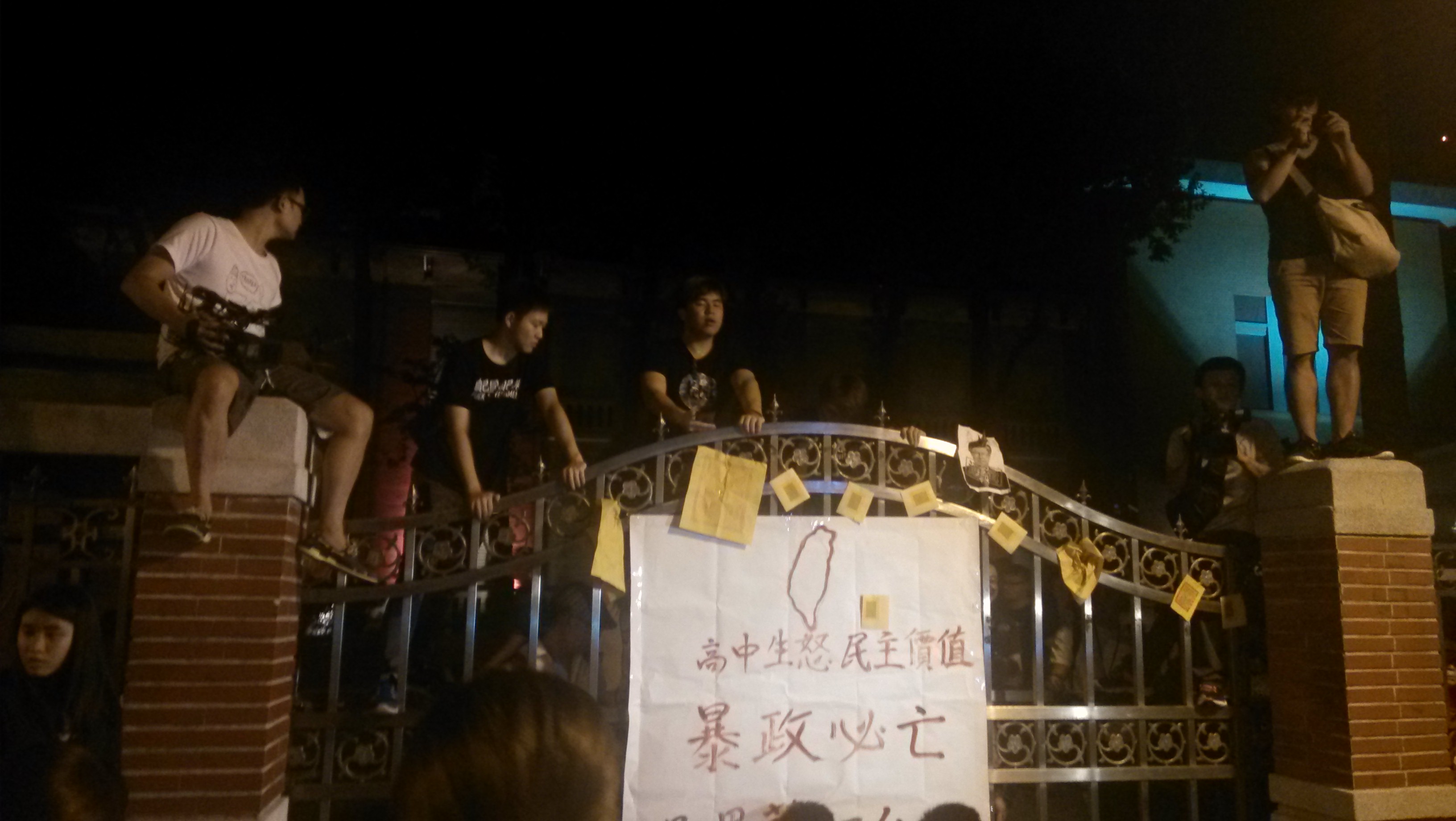

Students on top of the front gate of the Legislative Yuan on July 30th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Students on top of the front gate of the Legislative Yuan on July 30th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

And actually the occupation of the Ministry of Education courtyard was preceded by a brief moment in which several individuals got into the Legislative Yuan and a crowd overran the front gate of the Legislative Yuan, before the crowd moved to the Ministry of Education and it later forced down the razor wire fences outside of the Ministry of Education. Though I unable to confirm, from what I am told, the several individuals who got into the Legislative Yuan would seem to have actually gotten away and later joined the crowd outside of the Ministry of Education.

But, of course, there was much which was familiar about the occupation of the Ministry of Education courtyard. As during the Sunflower Movement, a large, self-organized encampment formed to sustain the occupation, with tents, refreshments, and artworks which sprang up to decorate the space inhabited by the movement. Though never as large as that of the Sunflower Movement, given that the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement was never as all-encompassing of society, the parallels were uncanny—this even moreso because the architectural layout of the Ministry of Education courtyard was nearly identical to that of the Legislative Yuan courtyard. As with last year, during the encampment, a phalanx of riot police blocked off the entrance to the Ministry of Education building or the entrance to the Legislative Yuan, and another phalanx of police was positioned on the side to guard a side door of the building.

Police in front of the Ministry of Education entrance. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Police in front of the Ministry of Education entrance. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

However, as reflective of the lesser amount of participants and perhaps as well the relative inexperience of high school activists compared to college activists, the division of labor in the movement was not as sophisticated as the Sunflower Movement, in which teams emerged to organizing the cleaning of the encampment around the Legislative Yuan, to handle distribution of supplies, or to handle media. In particular, we point to where the media strategies of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement were never as sophisticated as those of the Sunflower Movement.

After all, during the Sunflower Movement, a translation group with numerous linguistic subdivisions was formed to distribute information about the movement to international media by way of translation. We did not see anything so sophisticated this time around. There was, in fact, at times a disinterest among participants in speaking to media, even when it was international media. And though we can also point to the lesser number of participants or the absence of any singular leader figures in the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement as Chen Wei-Ting or Lin Fei-Fan of last year’s Sunflower Movement, certainly this disinterest in seeking media coverage was a factor in why there were less media coverage of the movement and why international coverage was lacking.

Public Discourse in the Anti Textbook Revision Movement and Sunflower Movement

AS WITH THE Sunflower Movement, part of where the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement sought and won over public approbation was because of the privileged role of students in Taiwanese society, in which students are viewed as morally pure and arbiters of innocence, in some sense. We saw this most prominently, perhaps, in regards to the public confrontation between student occupiers and Minister of Education Wu Se-Hwa, during which student occupiers broke down in tears publicly and this was captured on camera and circulated through the media. But on the flip side of this discourse was when students became condemned by public morality and were seen as unruly, socially disruptive troublemakers.

Within protest discourse itself, we see much the same between the movements, for example, where they targeted a central figure upon which all the woes of the movement were blamed. In the case of the Sunflower Movement, this was usually President Ma Ying-Jeou, but also Jiang Yi-Huah after the attempted Executive Yuan occupation. With the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement, the targeted individual was Minister of Education Wu Se-Hwa, who was blamed as having incited the death of Lin Kuanhua, in part for pursuing charges against Lin and adding to the pressure which led Lin to take his own life. This, of course, draws parallel to how Jiang Yi-Huah was referred to as an attempted murderer for condoning the police crackdown on would-be Executive Yuan occupiers. In both cases a singular figure was pointed out for blame, as though they alone were responsible for everything.

Protest signs at the encampment. Note the caricature of Wu Se-Hwa on the left. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Protest signs at the encampment. Note the caricature of Wu Se-Hwa on the left. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

However, where the present movement may have been clearer in the message it presented of itself in public discourse than last year’s Sunflower Movement was the clear and concrete demands made by the movement: first, to withdraw the planned textbook changes and, second, for Wu to resign. In the end, neither demand was fully met, Wu still remaining in power, and the textbooks being sent back to the Ministry of Education for review but a special legislative session not being called about the issue, as students had hoped.

Nevertheless, apart from that the impending typhoon due to approach on August 7th added to the justifications for eventual withdrawal, the inchoate nature of the Sunflower Movement led it to drag on some close to two weeks after it’s high point, with no grounds for deciding what conditions would sufficient for withdrawal would be because of the lack of concretized demands from the movement itself. Even if largely accidental in this way, the exit strategy of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement was cleaner because of the clearer demands made from the get-go.

The Relation of Students to Politicians, Police, and Other Authority Figures, Between Both Movements

PERHAPS REFLECTIVE of the changes in Taiwanese society which have taken place since after the Sunflower Movement, it is interesting to note that many of those who had participated in the Sunflower Movement as activists would visit the Legislative Yuan encampment as sympathetic politicians. This is indicative of the entrance of Taiwanese civil society into politics since the Sunflower Movement.

However, as compared to last year, the DPP had a decidedly more muted presence in the movement, where last year it showed up in force and established a base camp on the side of the Legislative Yuan. Presidential candidate Tsai Ing-Wen made a late night visit to the encampment shortly after midnight on August 3rd but this was not a highly publicized event. It may be that the DPP is focusing its energies on the upcoming 2016 presidential election and participating in another social movement would be distracting of or discrediting to its election aims. The DPP was, of course, accused last year by conservative forces of society of orchestrating the Sunflower Movement through inciting youth.

Ko’s visit to the Ministry of Education encampment on the last day of the occupation, on August 6th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Ko’s visit to the Ministry of Education encampment on the last day of the occupation, on August 6th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Actually if Taipei mayor is now the decidedly more sympathetic Ko Wen-Je, who was largely put into power by Taiwanese civil society, the actions of police against occupiers was restrained by Ko’s influence. Ko’s control over police was hardly absolute and he at least claimed to be unable to prevent the actions of police which took place on July 23rd during the first invasion attempt of the Ministry of Education. But Ko promised to restrain police in the future and this may have been a reason why there was minimized direct conflict between police and protestors on the night of July 30th when the Ministry of Education courtyard was occupied. Even as police raised the three warning flags which would be raised before a forcible eviction after protestors tore down the razor wire walls surrounding the Ministry of Education, they did not actually take action against protestors.

Ko’s influence can also be seen in that police moved in to forcibly disperse former gangster and pro-China politician White Wolf Chang An-Lo and his supporters when he showed up with several hundred of his supporters and hosted a rally near the Ministry of Education. However, central government may have still been willing to take action independent of Ko; for example, when a water cannon truck registered to central government was spotted behind the Ministry of Education building, with water pipes hooked up in preparation for possible use.

The Relation of Sunflower Movement Participants and Anti-Textbook Revision Movement Participants

APART FROM THAT the organizers of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement were largely younger high school students who may have not participated in last year’s college student dominated Sunflower Movement, notably Sunflower Movement activists kept out of the way of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement. Even if last year’s Sunflower Movement participants often did participate in demonstrations and actions—I recall running into Chen Wei-Ting during the first night of the Ministry of Education occupation at close to 3 AM, for example. Never mind that the night of the Ministry of Education occupation on July 30th was the only occasion which had brought together the individuals I had participated in 318, 324, and 330 actions with in the year which had passed since since.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

But this was often on an individual basis. Groups which had been formed by Sunflower Movement activists as Taiwan March or the Black Island Youth Front largely kept out of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement even as members participated on an individual basis, making way for a host of lesser known, younger high school groups. As already mentioned, political parties which had been formed out of Taiwanese civil society had speakers at the rallies, but we might also note the large number of Free Taiwan Party and New Power Party members on-site at the occupation encampment, although more the former than the latter.

However, going forward, if the present movement was a movement of high schoolers rising up just as last year was the movement of college students rising up, what is next? The movement of middle schoolers? That seems unlikely. Where a visible split had developed between college students and high schoolers during the Anti-Textbook Revision campaign before the start of the Ministry of Education occupation concerning tactics, organization styles, and end goals, this is yet to be resolved. Perhaps the challenge of the future, then, will be for Sunflower Movement and Anti-Textbook Revision Movement activists to find some way of finding common ground for cooperation.

What Now?

IN FACE OF the exhaustion which set in to Taiwanese civil society after the Sunflower Movement and which has not fully faded in the present—maybe another factor behind the smaller size of the Anti-Textbook Revision Movement—one would normally expect a movement like this to come ten years after the Sunflower Movement, not scarcely a year later. Certainly, although we can expect various mini-protests to sprout up about different issues in the lead up to 2016 elections, some exhaustion will set after the end of the occupation.

The question then is that to address Taiwan’s continued democratic crisis, will it be necessary for Taiwan’s young to rise up every year? If so, that would actually minimize the efficacy of protest, because the Taiwanese public would probably get tired of young people forever raising a fuss about such issues year after year and conservative discourse about students being unruly disrupters of social order would set in.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The fight is far from finished. In truth, the present textbook controversy is not totally settled despite the promises that have been won from the government—indeed, not even last year’s question of free trade agreements is settled, as we can see with the outbreak of protests because of the Ma administration’s desire for Taiwan to apply to the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, for example. In similar vein to that the Sunflower Movement apparently did not teach the Ma administration to drop the issue of trade agreements signed with China, whether through textbooks or otherwise, there may be continued attempts made by the KMT to install a more Sinocentric education in the future. So protest can and likely will occur. But where do solutions lie?