Eastern Taiwan Developmentalism, Settler Colonial Governance, and the Dispossession of Katratripulr Lands

by Yu Chen Chuang and Chia-Shen Tsai

語言:

English

Photo Credit: 潘立傑 LiChieh Pan/Flickr/CC

IN 2016, when the Taitung County government announced they were stopping construction of a baseball court on the Zhiben wetlands—the traditional territory of the Katratripulr tribe of the Beinan Indigenous people—the tribe did not anticipate that they would split into factions during their next fight against a new construction project on their land. In the four years since, the Katratripulr people and environmentalist groups such as Society of Wilderness and Taitung Wild Bird Association have gathered in front of the Executive Yuan in Taipei twice in protest of the most recent construction controversy. In contrast to previous construction projects in Zhiben that have been blocked by protestors since the 1980s—including an amusement park, a golf course, and the aforementioned baseball court—the most recent construction controversy concerns an ostensibly “environmentally friendly” green energy facility: a solar farm.

The construction controversy intertwines concerns around ecological conservation, energy transition, and Indigenous sovereignty. In light of the Tsai administration’s energy transition goal of building 20GW of solar energy capacity by 2025, the PV firm has promoted the solar farm construction project with the discourse of “mitigating carbon emission.” The environmentalists, however, have expressed concerns over preserving the ecological diversity of the Zhiben wetlands. This tension reflects a growing trend since the 2010s of environmentalist groups having to navigate between the urgency of sustainable energy transition and conflicts with other environmentalist causes like conservation, such as in the most recent Datan Reef controversy.

While we acknowledge this tension between energy transition and ecological conservation, we contend that the Zhiben solar farm controversy is best analyzed from the perspective of county-level developmentalism and infringements upon Indigenous sovereignty. In this article, we demonstrate how the history of settler colonialism in Taiwan and the developmentalism of the Taitung County government’s public-private partnership deals combine to produce the controversy surrounding the Zhiben solar farm project. By doing so, we draw attention to the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous land in the broader context of the unfinished project of transitional justice for Indigenous peoples in Taiwan.

The Zhiben Wetlands and Indigenous Land Dispossession

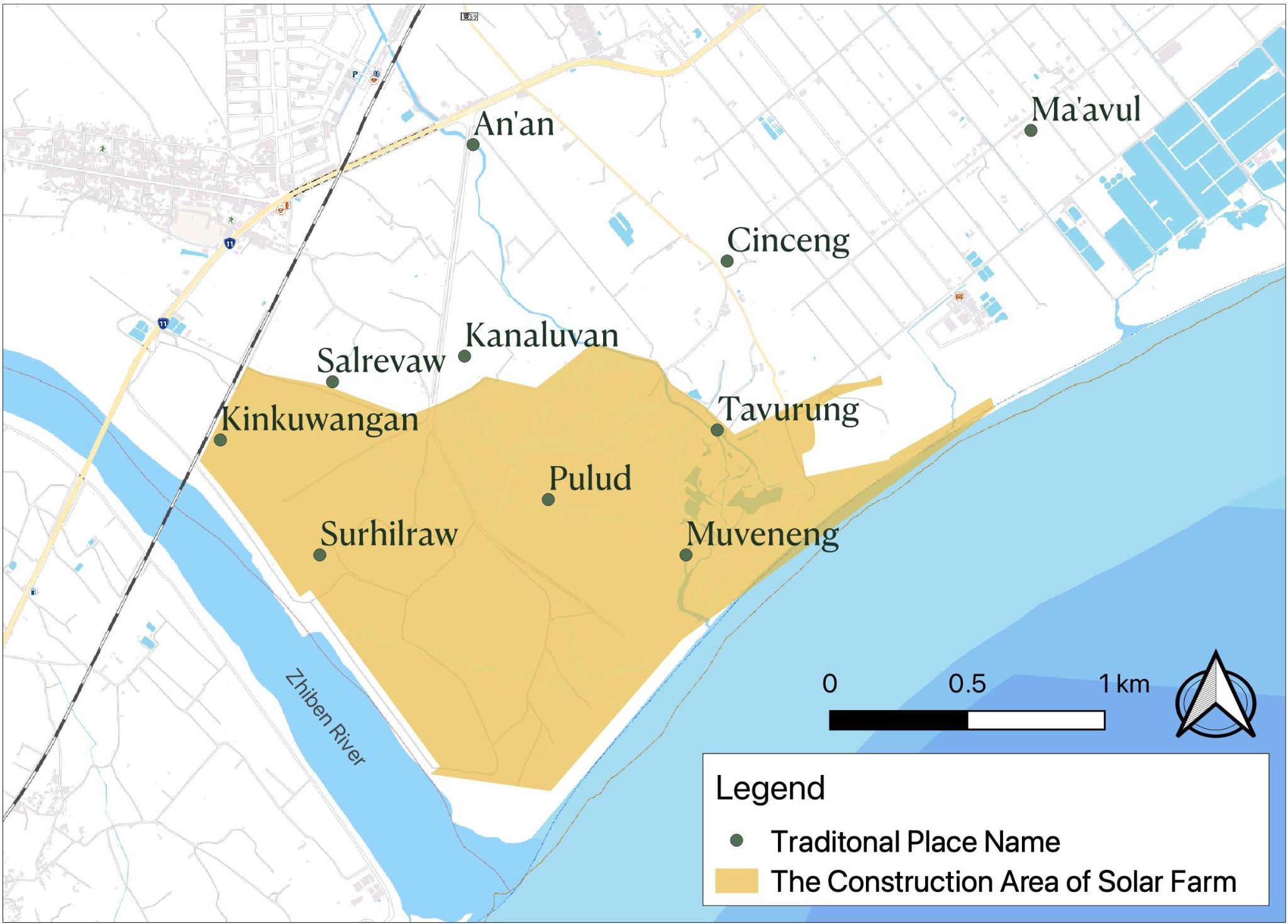

THE ANCESTORS OF the Katratripulr tribe have lived in the area known today as the Zhiben wetlands since at least the 17th century. According to cultural and historical research initiated by Katratripulr tribal members in 2014, place names throughout the Zhiben wetlands originate from the Katratripulr (see Figure 1). For instance, the Pakaruku family clan has lived in Kanaluvan—which means ‘marshland’ in the Beinan language (卑南語)—since the 17th century. The Katratripulr also named some places after the surrounding natural environment: for example, Muveneng means ‘the place where water gathers’, Tavurung means ‘downstream of the river’, and Pulud means ‘riverland’. In addition, Katratripulr peoples named some places after specific activities, such as Surhilraw, which means ‘the area for fish-catching’.

Traditional place names such as these represent the living experiences and memories of the Katratripulr people. According to Katratripulr oral history, a Dutch colonizer shot a Formosan sambar deer and frightened the tribe at Kinkuwangan, which means ‘the place where the shot rang out’. Katratripulr elders today still remember when they lived on their ancestral lands before they were forcibly removed by a Taitung County development project in 1985. These displaced elders used to herd cattle at Muveneng, catch fish at Surhilraw, and cultivate millet at Pulud.

Figure 1: Traditional Place Names of the Katratripulr Ancestral Lands in Zhiben. Source: 《心知地名:Katratripulr 卡大地布部落文史紀錄》

Figure 1: Traditional Place Names of the Katratripulr Ancestral Lands in Zhiben. Source: 《心知地名:Katratripulr 卡大地布部落文史紀錄》

The Zhiben solar panel controversy comes as no surprise given that the Taitung County government has repeatedly recruited private sector investments for various development projects, such as the Meili Wan hotel resort, along the eastern coastline. Furthermore, the majority of lands along the east coast are the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples whose ancestors lived in the area long before encountering settler colonizers in the 17th century. While Taitung County technically owns most of the Zhiben wetlands, the Taitung government does not have the right to develop this land in any way it chooses. To understand why this is so, we must take into consideration the colonial history of Indigenous land dispossession that led to the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples such as the Katratripulr tribe becoming public lands owned by settler colonial governments such as in Taitung County.

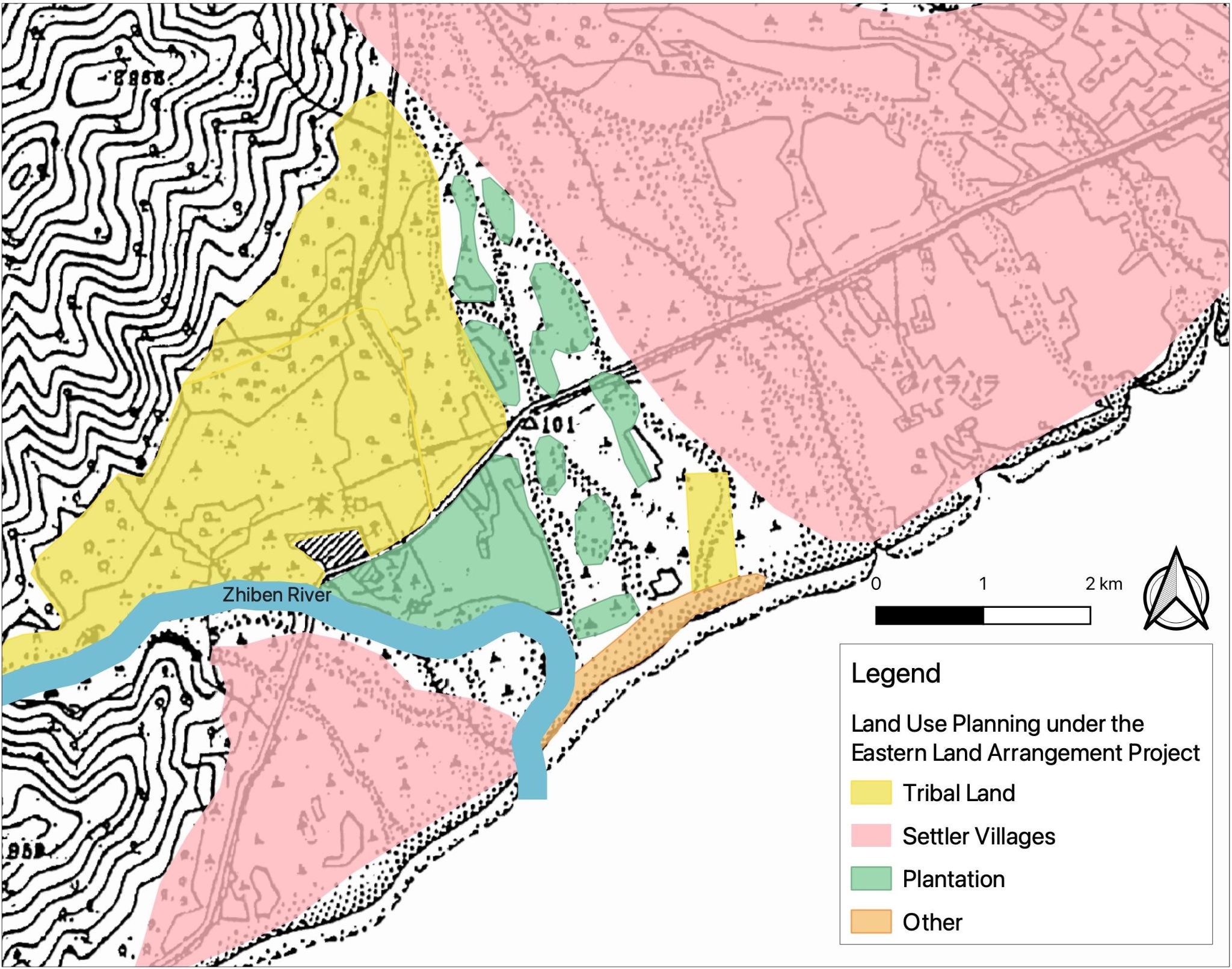

The story of Indigenous land dispossession in current day Taitung can be traced back to 1910—since the prior settler colonial regimes of the Dutch, Spanish, Ming, and Qing never initiated island-wide control—when the Japanese colonial government started to expand its rule into eastern Taiwan. The colonial government regarded the sparsely populated lands in eastern Taiwan as a perfect area to build settler villages for Japanese people and establish commercial plantations to plant highly profitable agricultural goods such as sugarcane, ramie, tea plant, and quinine. Hence, from 1910 to 1925, the government implemented the “Eastern Land Arrangement Project” (東部土地整理事業), which restricted the living area and land use of Indigenous peoples so that the colonial government could control a more extensive swath of arable land in eastern Taiwan. Japanese land investigation officials demarcated the boundaries of each tribe based on the principle that every household could obtain 3.6 hectares, what the colonial government deemed as the minimum amount of land needed for subsistence.

Figure 2: Land-use planning under the Eastern Land Arrangement Project. Source: 臺東花蓮港兩廳管內土地整理ニ關シ決議ノ件

Figure 2: Land-use planning under the Eastern Land Arrangement Project. Source: 臺東花蓮港兩廳管內土地整理ニ關シ決議ノ件

Through the Eastern Land Arrangement Project, the colonial government not only relocated and constricted Indigenous peoples’ living areas, but also reoriented Indigenous peoples’ mode of subsistence from slash-and-burn agriculture and hunting to sedentary farming. Furthermore, the colonial government not only took control of Indigenous land and established settler villages and commercial plantations, they even sold some of this land to Japanese capitalists. In 1910, the area known today as Zhiben wetlands was demarcated as a plantation area owned by the Japanese colonial government. After 1945 under the Republic of China regime, the Taitung County government took control of the majority of the Zhiben wetlands, which were later targeted for profitable development in the 1980s.

Taitung County’s Elusive Development Dream

IN THE 1980S, when Taiwan was still under KMT authoritarian rule, Taitung County started renting public-owned land to private citizens under 20 to 50 year leasing contracts as a way to supplement the county government’s funds. In 1985, the first piece of Katatripulr ancestral lands was leased into private hands using a “Build-Operate-Transfer” (BOT) agreement—a public-private partnership that involves contracting private companies to build and operate large public infrastructure projects for a set term before transfering the infrastructure into public ownership.

A roadside ad at Zhiben for “Oriental Disneyland” in 1994. Photo Credit: 柯金源

A roadside ad at Zhiben for “Oriental Disneyland” in 1994. Photo Credit: 柯金源

Widely used in Taiwan since the 80s, neoliberal BOT agreements are used to reduce the burden of large projects on the government’s infrastructure budget by enlisting private capital. In July of 1985, the Taitung County government leased over 285 hectares of wetlands to Jay Tee Ler Limited Company to build and operate “Oriental Disneyland Amusement Park” (東方狄斯耐樂園) for a lease term of 50 years. While the Oriental Disneyland construction project eventually fell through due to land ownership disputes between different levels of government, residents’ access to the land was restricted throughout the lease negotiation process, which led to waste accumulation and the land falling into disarray.

BOT construction projects were proposed on Katratripulr ancestral lands again in 1999 and 2016 for, respectively, a golf course and a baseball court. The 1999 golf course project was stopped by joint protests from the Taitung Wild Bird Association and the Katratripulr tribe. Failing to learn anything from the 1999 protests, the Taitung County government did not even inform the Katratripulr tribe of their construction plans in 2016. Outrageously, the Katritripulr tribe first learned of the baseball court construction project when they saw the groundbreaking ceremony on television, adding further insult to the historical trauma of settler seizure of Indigenous land and indifference to Indigenous sovereignty.

Between 2010 and 2017, another outrageous infringement of Indigenous sovereignty took place near the Zhiben wetlands. Katratripul ancestral graves are located near the Provincial Highway No.11. The county government decided to build parks for citizens along this highway and hence told the Katratripulr tribe to disinter and relocate their ancestors to county-administered public graveyards.

Figure 3: There were at least 18 developing BOT plans using public owned land in Taitung between 1985-2010. Source: Taiwan Public Television Service

Figure 3: There were at least 18 developing BOT plans using public owned land in Taitung between 1985-2010. Source: Taiwan Public Television Service

The county government’s demand provoked outrage and protest amongst the tribe between 2010 and 2017. Then in 2017, the county government redesigned the park so as to include Katratripulr ancestral graves in a memorial section. This case is important not only because it prompted the Katratripul tribe to mobilize in opposition, but more importantly because it led the tribe to conduct research about their own history and draw out the boundaries of their traditional territories.

The Katratripulr tribe has been unified against all of these past projects; but in the most recent solar farm controversy, the tribe has faced multiple internal schisms.

The Zhiben Solar Farm Controversy and Indigenous Governance

WHEN THE SOLAR farm project was initially proposed in 2017, it would have been the largest solar farm across Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea, spanning 226 hectares. Sheng-Li energy firm, a subsidiary company of Vena Energy, won the BOT bid and committed to acquiring the Katratripulr tribe’s consent as a prerequisite to starting construction. While the construction project passed by a 187-173 vote in 2018, the procedure resulting in this vote contained many flaws, such as the legitimacy of the county government holding the vote in the first place, the inclusion of a non-tribal Indigenous village into the vote, and the unlawful admission of proxy votes. In light of these procedural issues, three Katratripulr family clan leaders—Mafaliu, Pakaruku and Ruvaniaw—filed a lawsuit to nullify the 2018 vote and suspend construction. The permit from the competent agency will not be granted until the final adjudication is reached.

The internal conflict caused by the Zhiben wetlands solar farm project within the Katratripulr tribe reflects the difficulties and challenges of fully implementing Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples Basic Law, which stipulates that governments and private parties “shall consult and obtain consent by Indigenous peoples or tribes, even their participation, and share benefits with Indigenous people” when engaging in development projects on Indigenous lands.

In 2016, the Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP) enacted “The Regulation of the Consultation to Obtain Indigenous Tribes’ Participation and Consent” (諮商取得原住民部落同意參與辦法) to regulate the procedure for implementing Indigenous peoples’ consultation and consent (C&C) rights. The CIP Regulation states that if an Indigenous tribe fails to hold the C&C procedure within two months of a project’s proposal, the county government may initiate the consult and consent procedure themselves.

Because Sheng-Li first approached the Katratripulr tribal council to obtain their consent for the construction project after it had signed the construction contract with the Taitung County government—effectively leaving no space for Indigenous peoples to negotiate the terms of the solar farm project—the council refused to engage in the C&C process and asked the county government to withdraw its contract with Sheng-Li and restart the development project with a consultation procedure that fully respects the autonomy and wishes of the Katratripulr tribe.

Despite this initial refusal from the Katratripulr tribal council, in 2018 the county government executed the C&C procedure on the tribe’s behalf by initiating the vote on whether to approve the solar farm. Taitung County was technically within the bounds of the CIP Regulation when it initiated the C&C procedure, though as the protests indicate, these regulations paradoxically constrain the Karatripulr tribe’s ability to exercise Indigenous sovereignty by granting Taitung County the ability to bypass actual collaborative consultation and negotiation.

In addition to these procedural flaws on when and with whom to initiate the C&C process, the CIP’s problematic Regulation also reflects the tensions between settler governmental structures and Indigenous governance. To facilitate the practicality of executing the C&C procedure under the existing administrative bureaucracy, the CIP defines “tribal members” through the state’s civil registration system. To be more specific, local governments have the authority to determine which tribes are affected by a given development project and thus eligible to engage in the C&C process.

Viewed from the perspective of this administrative bureaucracy, only people who are registered under the household registration within a specific tribe count as “tribal members.” That is to say, state-recognized tribal membership is entangled with people’s real estate ownership and their status under the civil registration system. The problem with this system of state-centric recognition of tribal membership is that Katratripulr people who have been engaged in tribal affairs but do not live in the tribal area are, under this settler bureaucracy, not eligible to vote in C&C procedures. Meanwhile, non-Katratripulr Indigenous people who own real estate in the Katratripulr traditional territories are eligible to vote. In contrast to the civil registration system and real-estate ownership, the Katratripulr people define membership through traditional lineages and whether or not people are engaged in tribal affairs.

While the protection of Indigenous rights such as the right to consultation and consent is crucial to this case, the more significant issue has to do with navigating tensions between settler governmental structures and Indigenous governance as exemplified in the question of tribal membership. These institutional flaws led to the debatable result of the 2018 solar farm vote, to which certain Katratripulr members raised the following fundamental question: How can settler government institutions be designed and operated in coordination with the various and changing cultures of Indigenous peoples in Taiwan? The answer to this question is still unclear; it remains to be seen how the Taiwanese government will fulfill the promises stipulated in the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law without ignoring or overriding Indigenous peoples’ autonomy and cultural norms around governance.

On May 7th, 2021, Katratripulr tribal members protested outside the Taitung County government building in response to the decision to renew the government’s contract with Sheng-Li energy firm and extend the project’s timeline for completion by another six months. Led by the three Katratripulr family clan leaders previously mentioned above (Mafaliu, Pakaruku and Ruvaniaw), protestors demanded that the government withdraw the solar farm project due to the procedural flaws in the C&C process. On the other hand, tribal members who support the project also gathered there and requested the opposition to respect the result of the vote. Indeed, tribal members have various and at time conflicting visions for how they should engage development projects on their lands.

C&C rights were designed to ensure Indigenous peoples’ participation in and consent over the development of their traditional territories. However, the CIP’s existing regulations over C&C procedures do not adequately facilitate discussion and negotiation amongst Indigenous peoples over intratribal differences and competing visions; instead, these regulations intensify conflicts between different camps, contributing to internal divisions. In the case of the Katratripulr tribe, the so-called “consultation and consent” vote involved voting ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on a construction project proposal that the tribe did not have a hand in drafting or negotiating. Due to a lack of institutional space to discuss and negotiate between different visions of Indigenous development, the Katratripulr tribe did not even have a chance to reach a consensus on the solar farm project before being coerced into a zero-sum, ‘yes’ or ‘no’ vote.

Conclusion

SINCE THE JAPANESE colonial period, various levels of government have implemented construction plans reflecting different imaginaries of development in Eastern Taiwan from settler villages and commercial plantations to coastline resorts and amusement parks—all of which are founded on the constant dispossession of Indigenous land. Although in 2005 the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law was enacted and in 2016 President Tsai apologized to Indigenous peoples on behalf of the ROC government for the historical injustice and mistreatment they have endured, the controversy surrounding the Zhiben solar farm project indicates that realizing Indigenous sovereignty and rights in Taiwan still has a long way to go.

The Zhiben solar farm construction project is still suspended and awaiting final adjudication by the Supreme Administrative Court. Please stay tuned for subsequent updates.

[1] 孟祥瀚(Meng, Hsiang-Han)2003〈日治時期東台灣成廣澳的林業整理與土地調查〉 [The Land Ownership Survey and Forest Arrangement in Ginkongour under the Japanese Rule: The Amis Tribes Case, Eastern Taiwan]。《東台灣研究》 [Journal of Eastern Taiwan Studies] 8: 59-91。

Yu Chen Chuang previously worked in the Subcommittee on Land Claims of the Indigenous Historical and Transitional Justice Committee and is currently a master’s student in planning at the University of Toronto.

Chia-Shen Tsai, born and raised in Taichung, is an apprentice of anthropology and sociology. From rural care to environmental issues, he is fascinated by the gaps between various progressive agendas. He currently works for the environmentalist group Citizen of the Earth, Taiwan.