by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

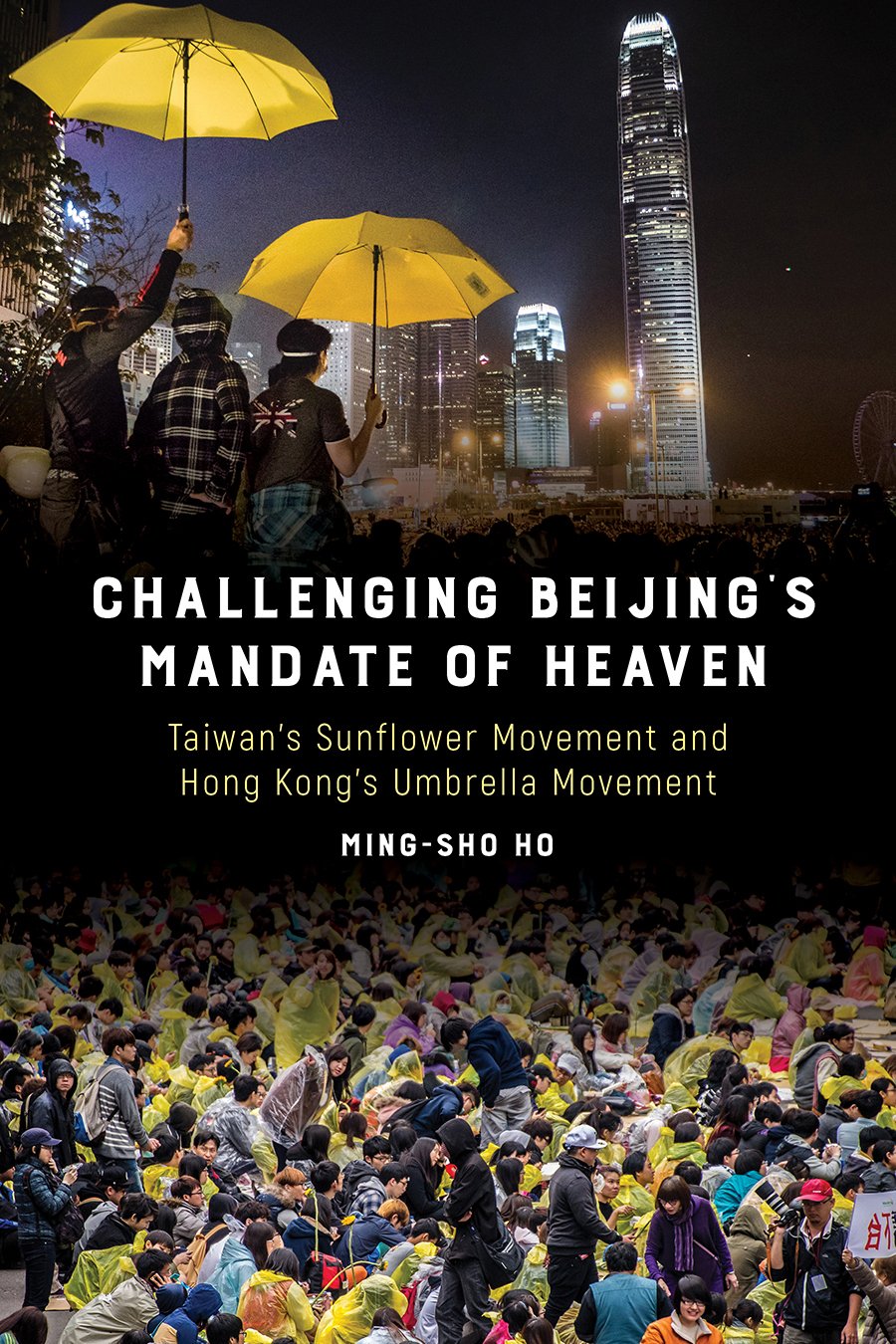

Photo Credit: Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven

HO MING-SHO’S Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement proves a significant English monograph comparing and contrasting the Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement. Ho ultimately paints a picture of two movements that diverged paths, while also accounting for their structural similarities and similar timeframes. At the same time, Ho is seeking to address larger questions regarding structure versus personal agency, with regards to what determines the outcome of social movements as well as what leads to splits within social movements, while also seeking to account for hard to quantify subjective factors.

Cover of Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement

Cover of Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement

Ho benefits in his analysis from his wide-ranging interviews with both Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement actors. Indeed, given Ho’s proximity to participants in the Sunflower Movement, Ho benefits strongly from his in-depth knowledge of the decision-making processes of key figures of the Sunflower Movement, including both student activists, NGO members, and academics. There likely does not exist in English any more succinct account of the course of the Sunflower Movement, its key events, and the turns and twists of the movement which led to the movement’s various political outcomes. Ho’s interviews on the Hong Kong side also prove extensive, including many key figures of the Umbrella Movement.

Likewise, a strength of Ho’s work is its ability to describe and draw out many of the political contradictions present in the movement. This includes Ho’s argument that the leadership within the Legislative Yuan, in fact, benefited from the police cordon that cut them off from the outside world because this also blocked off challenges to their authority. Or that even members of the leadership within the Legislative Yuan felt uncomfortable regarding the centralization of authority within the movement in their hands, in a manner resembling the oversight of executive power they opposed.

Nevertheless, the most interesting thread which emerges from Ho’s work is with regards to where the Umbrella Movement and Sunflower Movement diverge. In Ho’s account, the Umbrella Movement took place under conditions in which social movement and NGO actors had greater preparation and resources available, but the eventual outcome of the movement was arguably less successful than the Sunflower Movement. This would be as a result of a number of causes, including the greater trust which existed between Sunflower Movement student activists, NGO groups, or political parties, and the greater experience possessed by many Sunflower Movement student activists relative to Umbrella Movement activists.

To this extent, Ho’s account of the Umbrella Movement spiraling out of control of its original leaders—whether that be in the form of student activists or the three leaders of Occupy Central with Peace and Love—also seems to suggest that while both movements were far from leaderless movements, the Sunflower Movement’s greater success may have been because it did not become a decentralized, spontaneous movement. As such, Ho’s view of both movements challenges the romantic view of popular movements as successful because they are decentralized, by virtue of the wisdom of the masses or as organized through social media, instead suggesting that social movement leadership plays a key role in movement outcomes.

The occupied Legislative Yuan during the Sunflower Movement. Photo credit: VOA

The occupied Legislative Yuan during the Sunflower Movement. Photo credit: VOA

In analyzing both movements together, apart from the fact that they were both opposed to Chinese influence in some form, Ho also points to some of the structural, perhaps cultural points of comparison between both Hong Kong and Taiwan. As Ho points out, both were radical movements in conservative societies and took place in societies in which students were valuated as morally pure social forces. Although touched on briefly, one also imagines that one could suggest that a temporal point of comparison could also be useful, seeing as the Umbrella Movement marked Hong Kong beginning to grapple with certain issues that Taiwan has grappled with for decades, and that this may also be a starting point for some of the differences between the two.

All in all, Challenging Beijing’s Mandate proves essential reading for those interested in a deeper understanding of the Sunflower Movement and Umbrella Movement, particularly the former. Despite being primarily an academic book, the text still remains accessible and it is a source of information available little else in the English language.