by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: The Edge of Night/Facebook

THE EDGE OF NIGHT proves a deft, enthralling depiction of a crucial moment in the Sunflower Movement—the attempted occupation of the Executive Yuan that took place on the night of March 23rd and early morning hours of March 24th, 2014. [Full disclosure: The author of this review was a participant in the attempted occupation].

While the attempt to storm and occupy the Executive Yuan was an attempt to escalate the movement, as well as an expression of dissatisfaction with the leadership group of the occupation in control of the Legislative Yuan, the event proved controversial. Many members of the public reacted badly against what they saw as the Sunflower Movement overstepping its bounds in trying to occupy a second branch of government.

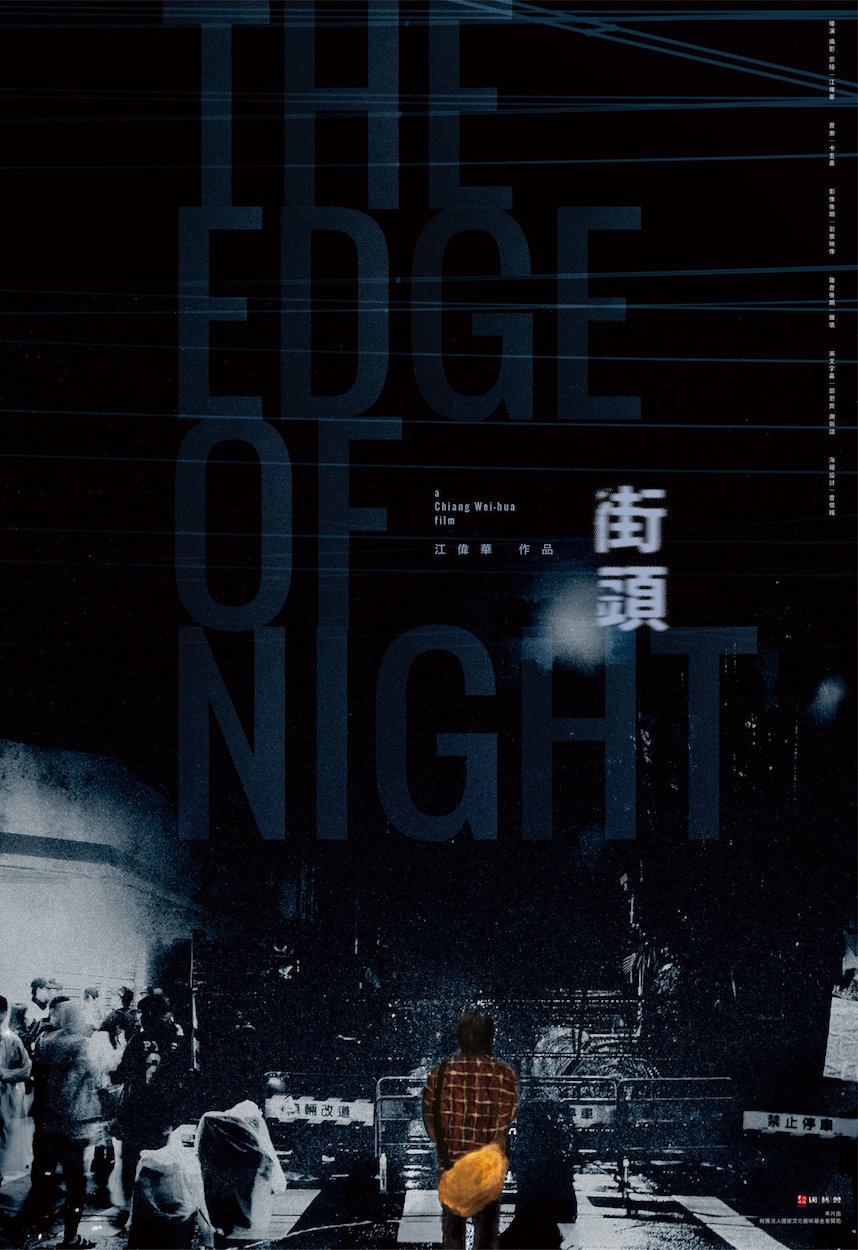

Film poster. Photo credit: The Edge of Night/Facebook

Film poster. Photo credit: The Edge of Night/Facebook

However, further controversial proved the use of police violence against would-be Executive Yuan occupiers, which some deemed to be the most severe use of police force in Taiwan since the martial law period. It is highly likely that the police force used against Executive Yuan occupiers was, in the long run, something that drew a great deal more public attention to the Sunflower Movement, building up towards the demonstration of 500,000 individuals on Taipei city streets that took place on March 30th, 2014.

The Edge of Night, then, focuses on the planners of the attempted Executive Yuan occupation, following how they became part of the NTU Department of Social Sciences command center group and felt increasingly dissatisfied with how the occupation within the Legislative Yuan was proceeding. The film follows the events that led them to plan the Executive Yuan occupation, while also highlighting the conflicted feelings of the planners of the occupation, their personal lives, and how by the time the Sunflower Movement ended, they felt largely marginalized from the events.

Chiang Wei-hua, who directed the film, also directed the 2010 documentary The Right Thing, which focused on the organizers of the 2008 Wild Strawberry Movement that was a predecessor movement to the Sunflower Movement. Key figures of the Sunflower Movement first became politically active in the course of the Wild Strawberry Movement and Chiang benefits from the long years of trust he has built up with his subjects.

In this, the editing of the film truly shines, Chiang smoothly cutting between six years of activism as he profiles some of his subjects, with footage of the Wild Strawberry Movement, protests regarding land evictions in Dapu, Miaoli, the Anti-Media Monopoly Movement, and other protests. To this extent, Chiang was also allowed access into key decision-making meetings regarding the planned Executive Yuan occupation, making his film a rare public record of decisions that later became an object of much controversy among activists. This footage shows many of his subjects at their most unguarded.

Photo credit: The Edge of Night/Facebook

Photo credit: The Edge of Night/Facebook

The film includes a panoramic view of the 23 days of the Sunflower Movement as a whole, but as a film which primarily focuses on the Executive Yuan incident, Chiang ably builds up narrative tension until it explodes in the course of the events later known as “324”. The depiction of “324” is striking, particularly for those who participated in the action and experienced the police violence that took place that night. Yet the film’s maturity is clearly visible in that the film, in fact, deliberately excludes an extended focus on events already too much in the public eye, rather than exaggerating their visual spectacle.

But the film’s depiction of its subject truly shines with regards to how it spotlights the actions of its main subjects after 324, including some of its subjects who later ran for office or visited Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. Indeed, two of Chiang’s subjects, Jiho Chang and Huang Shou-da, are now both DPP city councilors, and though the film does not follow either into their eventually successful election bids, the film highlights the political afterlives of the Sunflower Movement in a way rarely focused on to date.

This would be how the film benefits from being a film released five years after the movement, rather one released earlier. Likewise, this is how the film ultimately proves not a film simply about the Sunflower Movement, but a film about its subjects—a group of young people that sacrificed much for a cause that they believed in and had to reckon with the consequences of their actions for years afterward.