Could The Rise of South Asia Lead To A New Direction In Taiwanese Foreign Policy?

by Garrett Dee

語言:

English

Photo Credit: McKay Savage/Flickr

AT A DIPLOMATIC conference conducted by the DPP four months before the Taiwanese presidential elections, then-presidential candidate Tsai outlined her vision for the evolution of Taiwanese foreign policy under a DPP administration. Highlighting the democratic nature of countries such as Japan and the United States with whom Taiwan already enjoys a close relationship, Tsai made overtures to strengthening the partnership between these nations and Taiwan in her statement. Additionally, Tsai mentioned the necessity of building a stronger partnership with European nations, particularly in the energy and agriculture sectors. One of the biggest takeaways of the speech, though, was Tsai’s mention of a “New Southbound Policy”, a successor to the previous Southbound Policy which had governed the flow of capital from Taiwan into Southeast Asia. Citing Taiwan’s need to “diversify [its] economic and trade ties”, Tsai made mention that this New Southbound Policy would extend to governing Taiwan’s relationship with India, which she noted as being poised to become one of the world’s largest economies in the near future.

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-Wen Facebook page

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-Wen Facebook page

On the surface, it would appear that Taiwan and India share very little in common; although their governments both espouse democratic principles and invest heavily in the technology and telecommunications industries, they come from vastly different cultural and linguistic backgrounds and have not had a particularly long or noteworthy period of friendship or exchange. Like most countries who have significant trade relations with the People’s Republic of China, India does not formally recognize the legitimacy of the government of Taiwan. Where they share a critical mutual interest, however, is in their stated intentions to develop a more Asia-centric economic model moving into the future: India with its recent “Act East” policy and Taiwan with the “New Southbound Policy”. Additionally, both nations have long-standing grievances with the PRC and a vested interest in containing China’s imperialistic aggression in the Asia-Pacific region.

Recent trends in the balance of power in Asia seem to show India reascending to a more prominent role in the region after a period of stalled growth and underperformance. This reassertion of a strong Indian presence in the region comes at a time when China’s own rise seems fraught with complications, particularly those related to recent stock market troubles and underperforming growth rates. Though this heralded surge in Indian regional power may be marred by a number of serious complications such as high rates of poverty and environmental degradation, the addition of India to a potential Asian bloc (as I have mentioned in previous writing) would bring much greater weight to this hypothetical partnership of nations. As the PRC seeks to consolidate its already large influence in the region through policies such as its “nine-dashed-line” and financial institutions like the AIIB, nations like Taiwan and Japan that are more than slightly wary of a Chinese-dominated Asia should look to India as a potential major ally, one large enough to potentially counterbalance China’s strong attempts at gaining regional hegemony.

A Renaissance on the Subcontinent?

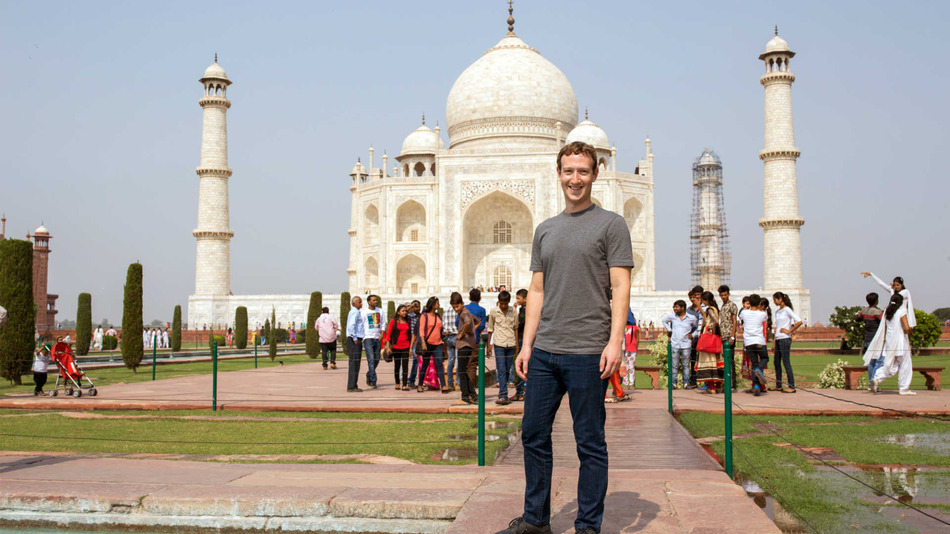

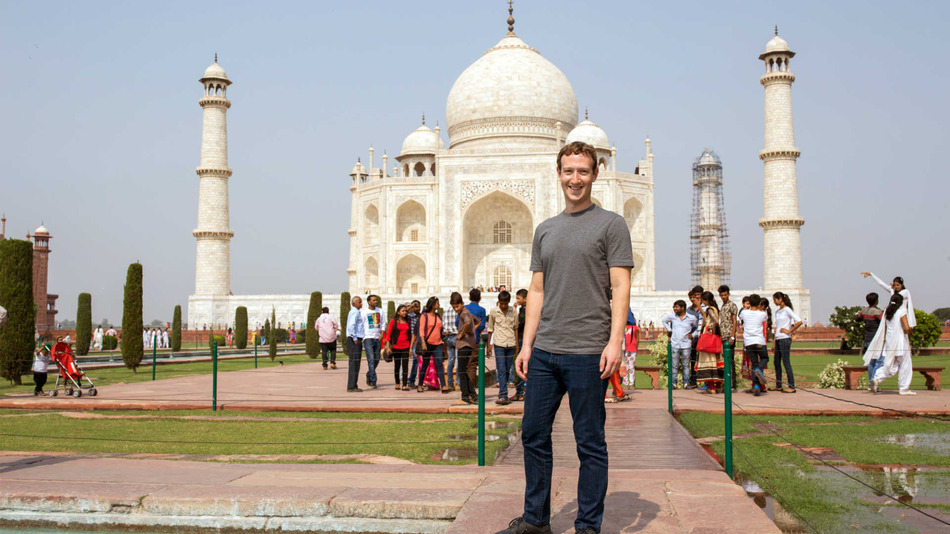

FOR ITS PART, India seems determined to follow its own trajectory of development rather than import a wholesale foreign economic model. An example of this is the recent snafu over Facebook’s proposed “Free Basics” plan in India, which the company heavily marketed as an innocuous plan to provide more than 600,000 Indian villages with broadband internet connection, but which was struck down by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India on the basis of violating the principles of net neutrality. The plan, though ambitious in its scope, would have provided unlimited access to a limited Internet, one in which Facebook would hold the position of arbiter in deciding which services would be prioritized over others. That India chose to reject this path of quick development as dictated by a powerful American corporation, opting instead for a trajectory toward broader connectivity in which it retained complete control, signifies its intention to break from the model adopted by many developing nations, in which modernization and westernization are accepted as inseparable concepts.

Mark Zuckerberg during a visit to India. Photo credit: Facebook

Mark Zuckerberg during a visit to India. Photo credit: Facebook

As one of the most widely recognized figureheads of the push of American influence in dictating the outcome of global development, Mark Zuckerberg’s reaction of incredulity that India would reject what he asserted as a benevolent plan to modernize and improve their country should come as no surprise. His delusion, however, is shared by much of the Western world when it comes to the idea of global development and economic activity. It has always been assumed that developing countries will be nothing but grateful to their Western benefactors for an influx of investment and new technology, regardless of at what cost these come to the sovereignty the nation’s people would realistically retain over the long-term development of their own societies. One cannot help but wonder at that Zuckerberg is truly surprised a nation held under the thrall of a repressive Western regime for the the better part of a century would resist an attempt by a wealthy American company to impose upon it an economic model in which it was at best a minority shareholder, but more than likely a mere observer.

It is not only in the area of economic policy that India has chosen to forgo allowing the United States to lead the way in its development; the nation has also shown a strong disposition to carve out its own dominant position in the security architecture of the region without assistance from the Western powers. Having completed a large scale fleet review in which over 50 nations participated as observers, the Indian Navy seeks to reassert its presence in regional waters, a move which may come in response to increasingly aggressive Chinese territorial expansion into these same seas. However, despite the fact that the United States Navy undertook a controversial Freedom of Navigation exercise in these same waters mere months ago, the India Navy dispersed any rumors that it would be partnering with the United States in this area by announcing that it would not be undertaking joint navigation exercises with the US fleet.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo credit: Wikicommons

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo credit: Wikicommons

This assertion of a nationalistic India power should not come as a surprise given the governing philosophy of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the leader of the conservative Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party who ascended to the Indian prime ministry with an overwhelming majority of the vote in 2014. Modi himself remains a controversial figure internationally, having been denied entry to both the United States and the United Kingdom following his alleged role in the anti-Muslim riots that accord in the Indian state of Gujarat in 2002, during we he was serving as the chief minister of the state. His role in the assertion of Hindu nationalism in the world’s largest democracy certainly cannot be denied, and his government has come under fire for its actions in suppressing protests and social movements, including its most recent movement against the student-led Leftist protests that occurred this February at the prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University. However, despite a number of setbacks incurred by the ineffectiveness of his party’s governance, Nehru has strongly advocated for a more advantageous position for India on the international stage, and has guided his nation to act more confidently in seeking its long-overdue status among the great powers, a status which seems more closely than ever within its grasp.

The Road Less Travelled: Taiwan and India

AN INDIA SEEKING to grow its own sphere of influence in Asia could prove to be a boon for the Tsai administration if it is indeed intent on moving away from a Sino-centric foreign policy. A fellow leader in the tech industry, India presents an increasingly viable alternative to the bulk of trade with China on which the Taiwanese economy currently relies. Despite large Taiwanese companies like Hon Hai having already established a presence on the Indian subcontinent, trade between the two countries in critical sectors like technology and communications pales in comparison to that between Taiwan and China. Though the Indian government is now seeking to actively implement policies that will encourage trade and foreign direct investment into its growing industries, India as a potential bastion of vital regional trade for Taiwan seems to have as of yet remained largely unexplored, with preference over the past decade being given to expanding trade relations with the PRC.

Despite this productiveness on the part of India in seeking out new trade and investment partners, however, trade between Taiwan and India all but stagnated during the years of the Ma administration, with latest figures showing the volume of trade between the two nations contracting in recent years despite an overall growth in Indian economic output. According the data provided by the India-Taipei Association, trade between the two nations consistently dropped during the period between 2013 and 2015, with every single month’s total trade in 2015 failing to reach the level of the same month the previous year, at times dropping by almost a third of the value. The Ma administration’s single-minded focus on expanding trade with China whilst simultaneously refusing to cultivate opportunities elsewhere has left the present Taiwanese economy seriously dependent on Chinese trade and blind to other sources of economic welfare. A smarter investment in alternative trade partners by the Tsai administration could reverse this trend and allow Taiwan more economic independence in the future.

Map of the Sino-Indian border, including disputed territories. Photo credit: Business Insider

Additionally, though it certainly would not show any outright support of Taiwanese independence, India does stand to gain from a regionally-weakened Beijing, who is not only its biggest global competitor in many of the same service and manufacturing industries that India seeks to dominate in the near future, but also more and more of a security threat as it expands its naval presence into the waters upon which India relies for much of its trade and economic livelihood. Despite a warming of relations over the years of rapid Chinese economic development, historical grievances over territorial disputes along the Sino-Indian border, as well as more contemporary issues like the Indian government’s harboring of the Dalai Lama, keep the relationship between the two large nations from reaching a friendly point. Following its stated course of deepening its alliances with regional partners in the Asia Pacific region as guided by its “Act East” policy, India as much to gain much from a partnership with Taiwan that has, until this point, been mostly overshadowed by Taiwan’s dependence on the Chinese economy.

Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

IT IS IMPORTANT to note, however, that this expansion of economic, cultural, and political contact should not serve to merely create wealth for those operating in the corporate and financial sectors of these two countries, and that the governments of the two nations, both long viewed alternatively as either untapped potential consumer markets or cheap manufacturers of goods and services, should work together to form a more sustainable and mutually-beneficial relationship. Tsai emphasized this point in her speech to the DPP, admitting that Taiwan’s previous “Southbound Policy” had focused mostly on Taiwanese investment in Southeast Asia, but that a “New Southbound Policy” would make investment merely one component of a multi-faceted approach that would also strengthen “people-to-people, cultural, educational, and research linkages”.

Furthermore, the Tsai government must be careful in monitoring its own commitment to human rights and questions of equality and fairness, in addition to monitoring the behavior of those with whom it chooses to engage economically and diplomatically. The propensity of the Indian government to aggressively push the concept of the Hindu nation into its governing policies is reminiscent of the Kuomintang’s own attempts to Sinicize Taiwan through protest suppression and textbook revision. Indeed, one could draw parallels between the actions of the Modi government in reaction to the Leftist protests at Jawaharlal Nehru University and those of the Ma administration in retaliation to the student-led Sunflower Movement and the occupation of the Legislative Yuan. The proposed committee to review the viability of the expansion of the Taiwan-India relationship could prove a beneficial first step towards greater freedom in the international community for Taiwan; however, the Tsai government should ensure that it is not leaving the support of one repressive regime for another.

It should also be noted that the forecasts of a continuation of India growth in strength and influence are far from universally positive, and that the Chinese economy’s recent bouts with financial and industrial malaise does not necessarily mean that it is on the verge of collapse. It would be unwise of the Tsai administration to put all of its eggs in one basket, betting completely on the rise of India against China and risking exposure to instability and harm should the projected rise of the Indian subcontinent’s power and influence become unsustainable in the near future.

That being said, it has long been taken for granted in discussions on the subject of Taiwanese foreign policy that the island lies permanently on the spectrum between China and the United States, oscillating between the two large great power nations depending on the balance of power in Asia and the state of the green-blue political divide in the Taiwanese government itself. However, a younger generation of citizens with a stronger belief in a more uniquely Taiwanese identity coupled with a incoming administration seeking a fresh direction politically could mean that the time is right for a more forward-thinking foreign policy, one that moves Taiwan beyond this dichotomous great power game and gives it more options for independent action. India is one among many such options the government would behoove the government to explore.

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-Wen Facebook page

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-Wen Facebook page Mark Zuckerberg during a visit to India. Photo credit: Facebook

Mark Zuckerberg during a visit to India. Photo credit: Facebook Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo credit: Wikicommons

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Photo credit: Wikicommons