by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

CONCERNS THAT Taiwan could face an imminent Chinese invasion have been stoked by recent comments by Admiral Philip Davidson and Admiral John Aquilino, the outgoing and incoming heads of the US Indo Pacific Command respectively.

Comments by Davidson and Aquilino were made in the context of two separate Congressional hearings, with comments by Davidson made during a budget review for the US Indo Pacific Command, and by Aquilino during a confirmation hearing for assuming the command of the US Indo Pacific. Davidson claimed that China could invade Taiwan within six years, while Aquilino stated that the threat to Taiwan from China is “closer than most think” and that the annexation of Taiwan was China’s “No. 1 priority,” claiming that China saw it as a matter of “national rejuvenation.”

Admiral Philip S. Davidson. Photo credit: US Embassy Canada/Public Domain

Admiral Philip S. Davidson. Photo credit: US Embassy Canada/Public Domain

However, to begin with, comments by Davidson and Aquilino need to be taken with a grain of salt. First, during a budget review, it is improbable that Davidson would downplay the threat to Taiwan. Emphasizing the threat would be a way to ensure that the US Indo Pacific Command is granted a higher budget and more operational authority. Moreover, in examining Davidson and Aquilino’s responses, one notes the similarity of their responses. Both were questioned on the Taiwan issue by the same Republican senators known for their hawkish views on China, such as Tom Cotton, and were likely playing to their audience.

In fact, one could scarcely imagine a scenario in which Davidson and Aquilino would downplay the threat to Taiwan posed by China in the Asia Pacific. To claim otherwise would be to annul the institutional raison d’etre of the US Indo Pacific Command.

Though unlikely, if Davidson and Aquilino had any Taiwanese audience in mind for their comments, comments by the two military officials may have been aimed at trying to pressure Taiwan into increasing military spending. The US has long claimed that Taiwan does not spend enough on military spending .

That being said, one notes that it was only until very recently that the US saw fit to transfer sensitive military technologies such as used in submarines. Bemoaning Taiwan’s lack of military spending, claiming that the US should scarcely be obligated to defend Taiwan when Taiwan was not doing enough to defend itself—and then refusing to transfer key technologies that could significantly alter the strategic calculus of a Chinese invasion—strikes as a form of blaming Taiwan while also refusing to take any action on the matter. Ironically enough, the US has partly justified such inaction by citing the possibility that technology transferred to Taiwan could fall into Chinese hands, then proved reluctant to transfer technology that could deter a Chinese invasion.

But, either way, a Chinese invasion is not going to occur in the short-term future. If there has been much fear-mongering as of late about China being willing to conduct an invasion of Taiwan once the necessary conditions are met, such conditions are not going to be met anytime soon and may not be met for decades. Imminent apocalypse scenarios are hardly warranted and prove counterproductive.

The Shandong, China’s second aircraft carrier. Photo credit: Tyg728/WikiCommons/CC

The Shandong, China’s second aircraft carrier. Photo credit: Tyg728/WikiCommons/CC

First, one notes that if China intended to invade Taiwan, this would be known in advance; it would be very difficult to hide the movements of Chinese troops massing in coastal regions in preparation for an invasion from detection by satellite imagery. It is unlikely there would not be some form of international response during that window of time, nor that the Taiwanese government would simply wait with its arms folded during that period for an invasion to take place.

Second, China lacks the basic lift capacity to transport sufficient troops to Taiwan in order to conduct an invasion and long-term occupation. China is working to develop this capacity, but some experts do not believe that this is a pressing priority for China at present. Regardless, it is not coincidence that China’s own timeline for an invasion of Taiwan is to retake Taiwan by 2049, with a gap of several decades allowing adequate hypothetical time to build such capacity.

Third, China would suffer enormous geopolitical and socioeconomic consequences from an invasion of Taiwan. Regardless of advances in Chinese technology over the past decades, when it comes to naval invasion, military science favors the defender; the estimates of the number of dead range from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands, some suggest that an invasion of Taiwan would likely be the largest naval invasion since D-Day, and it would involve the mobilization of hundreds of thousands of troops on both sides. In this, Taiwan is aided by its geography, due to the limited amount of beaches in Taiwan large enough to allow for a naval landing, and because of the yearly window for weather conditions allowing for an invasion being small. [1]

Likewise, an invasion would precipitate an economic crisis for both the Chinese and Taiwanese economies, which are already deeply interlinked. Given the size of the Taiwanese economy, just the Taiwanese economy going into crisis would have a catastrophic worldwide impact on par with or larger than the Greek economic crisis of 2009, much less both the Chinese and Taiwanese economies going into crisis at the same time. The Chinese economy was already slowing before COVID-19 struck.

Indeed, before contemplating a Chinese invasion, the Chinese government would have to be able to shrug off the tremendous blow to its political legitimacy from tens of thousands of casualties, after having not fought a war in over forty years. One observes how divisive an issue several thousand casualties from the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars was for American domestic politics; an invasion of Taiwan would result in losses many times that in magnitude, much less the human cost that would come in subsequent years from what would likely be armed resistance in Taiwan. As attested to by the 2014 Sunflower Movement or other mass protest movements, even if the military draft in Taiwan is often seen as inadequate training, resistance is more likely to occur than not; it does not require advanced military training to create improvised explosive devices or for guerilla tactics to take place. Armed resistance occurred during the KMT martial law period, including incidents of arson, bombings, and assassinations, and this is likely to occur under a Chinese occupation, as well.

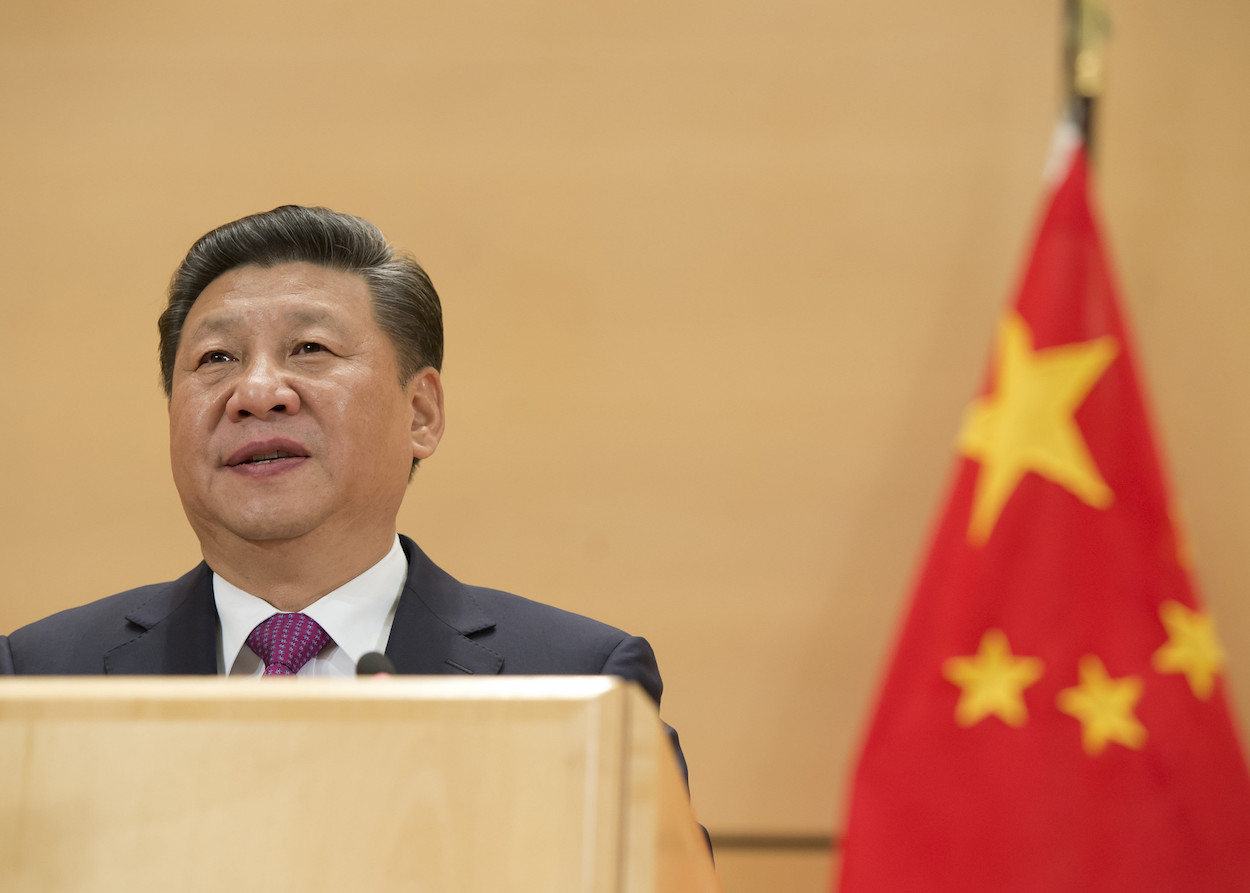

Chinese president Xi Jinping. Photo credit: UN Geneva/Flickr/CC

Chinese president Xi Jinping. Photo credit: UN Geneva/Flickr/CC

As such, in addition to the blow to credibility from significant loss of life from mounting an invasion of Taiwan, the Chinese government would simultaneously have to weather the blow to credibility from economic catastrophe. It is not likely that the Chinese government would be able to handle both crises at once anytime soon.

Consequently, the only scenario under which the Chinese government would conduct an invasion of Taiwan in the short-term future would be if it is fundamentally politically irrational. Having undone the term limits that a Chinese president can serve, but not achieved lifetime rule, one may be tempted to see Xi Jinping as willing to precipitate such a crisis in order to justify a power grab. But the gamble seems too great—Xi is more likely to use unrest in Hong Kong or Xinjiang as the political crises he will use to justify a gradual expansion of power, rather than a risky invasion of Taiwan that the blowback from which could result in his deposition from power.

The aforementioned scenario would occur with no intervention from neighboring countries or from the US. While the strength of American commitment to Taiwan is unknown, Japan in particular would face strong pressure to respond, due to its geographic proximity to Taiwan. One notes that Okinawa is geographically closer to Taiwan than it is to the rest of the Japanese archipelago. Key regional shipping routes also pass near Taiwan and would likely necessitate a response from other Asia Pacific countries.

China could potentially seek to mitigate risk by aiming to paralyze responses to an invasion by a decapitation strike aimed at killing the Taiwanese political leadership. However, one does not expect decades of contingency planning to evaporate overnight either. And an unorganized response could still be costly for China.

Otherwise, it has been suggested that China could try to strangle Taiwan slowly through a blockade. But it is unlikely that Taiwan would not respond militarily to a blockade, or that other countries would not respond—possibly even doing so in a manner that falls short of open warfare, through naval action that stops short of opening fire, or cutting off China’s access to necessary resources. Due to the fact that Taiwan has the capacity to hit targets on the Chinese mainland, China would hazard retaliatory strikes through a blockade. Cutting Taiwan off from oil supply would also lead to shortages in China which, too, would be affected by its own blockade or international actions in response to China’s actions; a Chinese blockade would not take place in a vacuum. Neither side could weather a protracted blockade, with Taiwan thought to have around a month of reserves, while China has around 80 days.

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

Much hand-wringing about so-called Taiwanese complacency about China comes from Taiwan’s apparent lack of reaction to increased attempts by China to militarily intimidate Taiwan in the past year. Certainly, complacency is an issue in Taiwan, but in this respect, neither is Taiwan completely helpless. As outlined, structural factors are on Taiwan’s side.

One notes that Chinese psychological warfare tries to drum up the threat of immediate invasion, to project toward the outside world that it might invade Taiwan at any given time—even if its own domestic assessments suggest a longer timeline for annexation, given the 2049 deadline that China has set for itself. China would optimally like to take Taiwan with as little human cost and as little disruption to trade as possible; given Chinese reliance on Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturing for its supply chains at present, China would similarly hope to avoid damage to infrastructure.

This is partly why China would like to obtain Taiwan through electoral means if possible through its proxy, the KMT. But one also notes that civilian resistance against China in the event of an invasion is less likely to happen if Taiwanese view resistance as futile. Military resistance is also unlikely to take place if troops are demoralized and unwilling to fight, with the view that their efforts will be for nought. Some may be tempted to fear-monger in hopes of shaking Taiwan outside of perceived complacency, but this could have precisely the opposite effect.

Much of Taiwan has grown accustomed to constant military threats over past decades, scarcely reacting to significant upticks in Chinese incursions into airspace near Taiwan or naval exercises over the past year as a result.

China’s inability to inspire fear and terror among the Taiwanese population can be attributed to its failure to build a narrative of progressively increasing threats to Taiwan, and how threats to Taiwan from China instead come across as repetitive and mundane. Likewise, China’s military threats are mixed in with a news cycle that quickly redirects attention elsewhere, between constant dashcam footage and stories of the mundane, failing to dominate the media narrative.

It should not be thought that Taiwan is indifferent to the China threat, simply because they do not react to what has by now long since become a recurring news item. In other words, Taiwanese are self-evidently not indifferent to the China threat, noting the electoral defeats suffered by the pro-China KMT in past years during consecutive presidential elections. and the party’s weak standing in domestic politics at present—particularly among young people, with the KMT having less than 9,000 members under 40 as of November last year. It has long been known that independence versus unification is the most salient split in Taiwanese politics and this does not look to set change anytime soon.

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

Photo credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

Such domestic electoral mobilizations against the KMT and pro-China political forces in Taiwan are better seen as illustrating Taiwanese reactions to the threat of China, rather than demeaning, infantilizing views of Taiwanese that see them as apparently failing to grasp the largest threat to their own political freedoms while others do.

And it ultimately may be to Taiwan’s benefit that the population does not constantly live in fear of China, demoralizing the population, but that concerns regarding Chinese threats to Taiwan resurface with regularity every four years. That is, paradoxically enough, this apparent indifference to Chinese military threats may be to Taiwan’s benefit—frustrating efforts by Beijing to psychologically intimidate Taiwan into the view that resistance is futile in a manner that would sap the will to resist—yet this does not illustrate that Taiwanese are not concerned about China either, given contemporary political trends in Taiwan that should be self-evident to any observer.

[1] Ian Easton’s work provides a useful counter-narrative highlighting the severe risks faced by China in mounting an invasion

Ian Easton, The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia, Manchester, UK: Eastbridge Books, 2017.