by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Lgh_9/Pexels/CC

THE NEED FOR labor protections for couriers and deliverers in Taiwan has become widely discussed in the past week. Namely, a large public reaction has ensued after two deaths of deliverers in traffic accidents and the death of a pedestrian struck by a deliverer.

The first death, of 29-year-old Foodpanda deliveryman surnamed Ma, took place last Thursday after his scooter collided with a truck driven by a 25-year-old man surnamed Tseng. The second death, that of a 20-year-old Uber Eats deliveryman surnamed Huang, took place Sunday after his scooter was hit by a car. A related incident was the death of a 70-year-old pedestrian surnamed Luo after being struck by the scooter of a 30-year-old Lalamove deliverer surnamed Zhou.

Photo credit: shoplocks/Flickr/CC

Photo credit: shoplocks/Flickr/CC

Much public discourse regarding the three deaths has focused upon the fact that online delivery services such as Foodpanda, Uber Eats, and Lalamove do not provide insurance, hazard compensation, or occupational injury benefits for their workers. Workers are instead defined as contractors, which excludes them from the provisions of the Labor Standards Act.

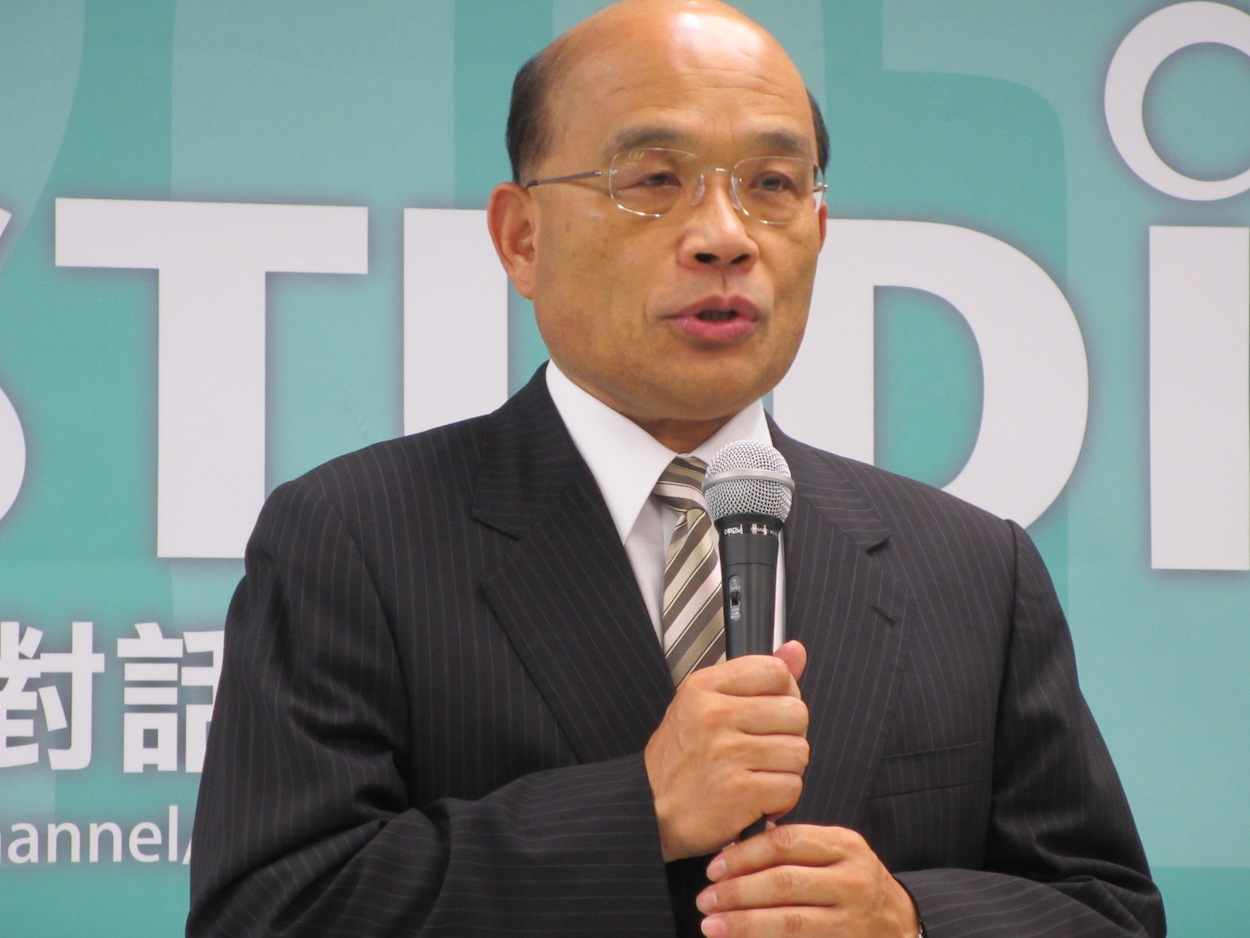

As a result, a number of politicians have been critical of the three companies, including Premier Su Tseng-chang, Financial Supervisory Commission chair Wellington Koo, DPP Taichung legislator Huang Kuo-shu, DPP Taipei city councilor Hsu Shu-hua, and NPP Taoyuan legislative candidate Lin Chia-wei. After being ordered to do so by Su, the Ministry of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration conducted inspections of Foodpanda and Uber Eats last week.

That being said, Foodpanda and Uber Eats have both stated that they do not intend to revise their labor regulations in order to make workers formal employees, rather than contractors. This may not be surprising, particularly given Uber and similar companies’ willingness to shrug off government regulation in order to maintain its business model, this done in the name of “disruptive innovation”. Foodpanda and Uber Eats both claim that the Labor Standards Act does not suit their business model.

Disregard for the law by Uber and similar companies has true whether in Taiwan or many other parts of the world, with Uber continually shrugging off government fines in order to keep operating and, in fact, designing its app in order to mislead efforts by law enforcement to crack down on its continued operations. In that way, Uber and similar companies have sometimes successfully forced national governments to the negotiating table by simply refusing to stop operating.

On the other hand, while discussion has primarily centered around the lack of insurance of deliverers and couriers, less discussion has focused on the fact that Foodpanda, Uber Eats, and Lalamove set strict time quotas on workers for efficiency, such as requiring that deliveries be made within fifteen minutes despite that couriers may receive orders every six minutes. As such, workers do not take breaks in order to meet their quotas, leading to accidents caused by exhaustion. On the other hand, a thirty-minute break is mandated every four hours under the Labor Standards Act.

Despite taking such risks, the company sometimes takes much of the pay for deliveries, such as taking up to 30% of the delivery order. As the deliverers or couriers who have had accidents to date were all young people, one notes that the so-called “gig economy” simply serves as a means to exploit the young and underprivileged by way of forms of precarious labor.

It also proves ironic that Su and other members of the Tsai administration have responded to the issues flagged by these recent incidents by suggesting bringing contract workers from services as Foodpanda, Uber Eats, and Lalamove under the auspices of the Labor Standards Act is how to resolve the issue.

Premier Su Tseng-chang. Photo credit: VOA/Public Domain

Premier Su Tseng-chang. Photo credit: VOA/Public Domain

Moreover, workers in many industries are already excluded from the provisions of the Labor Standards Act. This has historically been justified by the claim that the Labor Standards Act does not suit the specific needs of those industries. Nowhere is this truer than of workers in the transportation industry, whether that be with regards to bus drivers, airline workers as pilots, ground staff, and flight attendants, truck drivers, and train and MTR workers.

Exemption from the Labor Standards Act is used to justify forcing workers in such industries into overwork and exhaustion—in spite of that this proves dangerous for pedestrians, passengers, and workers themselves. Talk of bringing contract deliverers under the provisions of the Labor Standards Act fails to get at the heart of a much larger issue, then.