by Gabriel Ernst

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Matt Crampton/Flickr/CC

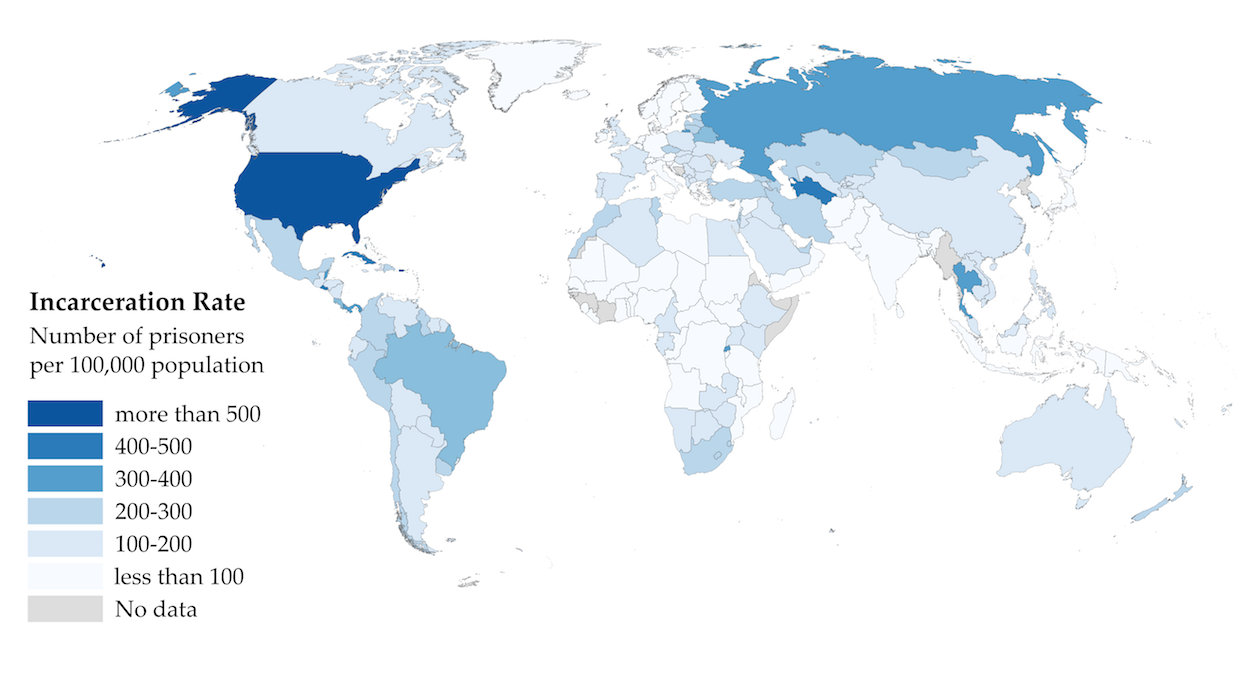

THAILAND IS NOT widely known as a carceral state, but with the world’s fourth-highest incarceration rate, it is one of the easiest places in the world to end up in prison. Ranking above it are the United States, Honduras, and Turkmenistan. Notably, Thailand also holds the title of having the highest rate of female prisoners. According to World Prison Relief, the current total prison population stands at 354,905.

Conditions for those in prison in Thailand are extremely poor, with 143 of 144 of Thai prisons reporting overcrowding. Due to this overcrowding, those who find themselves inside suffer from terrible conditions, with meager food rations, space shortages, and inadequate facilities. The carceral food budget is ฿49 (1.60USD) per day, which is capped at a prison population of 190,200. But the real prison population being near double that, as a result of which almost all inmates go without proper food.

Mass incarceration rates globally. Photo credit: Jannick88/WikiCommons/CC

Mass incarceration rates globally. Photo credit: Jannick88/WikiCommons/CC

According to the Thai Department of Corrections, more than half of those incarcerated are there for an “offense against narcotics law”. However, some reports put the percentage is closer to 70% or 80%. A government spokesperson even recognized the policy failures leading to this in 2016, stating that “The world has lost the war on drugs, not only [in] Thailand” and that “We have clear numbers that drug use has increased over the past three years. Another indicator is that there are more prisoners.”

Much of these arrests originate from the 2003 crackdown on drug use enacted by then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The 1997 Asian financial crash saw a huge drop in employment, which over the next few years led to an unsurprising rise in drug use. The crackdown saw far lengthier sentences for drug users and a mass police mobilization geared towards violent arrests and drug seizures, which one inquiry found led to over 2,800 extra-judicial killings in just three months.

Other than the legalization of medicinal marijuana earlier in 2019, there has been little to no reform of the criminal justice system’s treatment of narcotics since 2003. While the crackdown itself has ended, its architecture remains, with police activity still primarily focused on drug arrests and courts handing out lengthy sentences for relatively minor offenses. For example, possession of cannabis, even after its medical legalization, can result in as much as a 15-year prison sentence.

Outside of the prison walls, the burden of mass incarceration and the war on drugs is borne by the bottom of society. Bribes are commonplace in Thailand for minor violations such as small drug possession and driving infractions. Bribes and bail fees start as low as ฿200 (6.50 USD) for a minor driving violation but can be extremely costly for drugs charges, reaching as much as ฿40,000 (1,300 USD) to avoid prison time. If you can’t afford the cost, jail is the only option.

The effect this has on working-class families is brutal. Many are left without parents for extended stretches of time, going without the emotional and caregiving support—not to mention the financial support—of an earner in the family.

Photo credit: Sodacan/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Sodacan/WikiCommons/CC

Abortion is still illegal in Thailand and those in the lower classes can’t afford to go abroad or pay for illegal operations, hence the birth rate among the young and poor in the kingdom is relatively high. This coupled with a lack of labor protections, the absence of a welfare state and the mass incarceration rate makes life as a young working-class person extremely precarious. According to the United Nations Population Fund, the majority of Thai children in orphanages will still have both living parents, but they “may be unable to care for them due to poverty, imprisonment, or other reasons, such as teen pregnancy.”

Kay, now age 25, was 9 years old when his grandmother went to prison on drug charges, upon which she still maintains her innocence. “I was shocked, I felt confused because I didn’t understand why she had to go. For me she was the nicest person, it didn’t make sense.”

Kay states, “I visited her twice, I met her in the visiting room and we talked a little bit. It felt normal for me, since I was so young, sitting between the bars with my grandmother. She looked kind of happy, but I realize now it’s probably because she was seeing me.” Thailand’s prisons hold the largest incarceration rate of female inmates in the world. This raises questions about why so many women are targeted relative to other countries, what the police are looking for that leads them to arrest so many women. One assumes it has something to do with the large sex work industry; however, a lack of public data leaves these questions unanswered.

Six years after his grandmother was imprisoned, Kay’s father was arrested and sentenced for financial crimes. “Again I was shocked, I remember crying for my father, I knew that he would go in for over 2 years. When you’re a teenager that’s a long time. I was never able to visit him, because his prison was on the other side of the country.”

With such a high incarceration rate, for working-class people there is little stigma in having a family member in prison. “At that time I didn’t tell anyone. But it wasn’t because I was embarrassed about my social status. I didn’t care. I had other friends whose family went to jail it was normal. I didn’t feel like sharing, I was just sad […]”

Kay continues, “I’m still sad about it. Sad for my family members. I know that they had a difficult time in jail. In some places, it’s just so normal to go to jail, the worst thing is the money you will lose to get them out. It’s more of a frustration than an embarrassment.“

Photo credit: PXHere/Public Domain

Photo credit: PXHere/Public Domain

Upon release from prison, former inmates face immense difficulty reintegrating into society, dealing with the social stigma, adjusting their mindset to the outside world and finding gainful employment is no easy task after long stretches inside. This is by no means unique to Thailand but underscores the detrimental effects of confinement after release. Suicide is relatively common for people when they get out of jail after serving long sentences, as they come out with no friends, no job, no money, no prospects and very little support.

Numerous studies have proven that harsher prison conditions increases recidivism rates. The rate for first-time offenders in Thailand for 2016 was a staggering 73%. The Thai prison system clearly is not working and is a drain both financially and on the social structure in the Kingdom. While a number of reforms have been promised over the past 2 decades, a turbulent era of coups and failed elections has led to governance which can be described as shaky at best.

During the 2019 election, correctional system reform was notably absent from the discourse. The chances for any real kind of reform alleviating the suffering of the working class looks highly unlikely in the foreseeable future. Until then it is they who will bear the brunt of this carceral state, both inside and outside of jail walls.