by Alex Chuang

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival/Facebook

Catta Chou is the curator of the Taiwan International Labor Film Festival. On October 12, 2018, she was interviewed by New Bloom’s Alex Chuang regarding this year’s festival and the festival’s history. The Taiwan International Labor Film Festival will be held from October 20th to October 28th.

Alex Chuang: Could talk about how you were introduced to social movement organizing? Did you begin in college or before that?

Catta Chou: Well, I would have to say that I was very normal in high school, but after I entered into university, I joined the student club—the Black Ditch. We call it a yixing shetuan (異議性社團), meaning that people who talk about issues that are not normal or mainstream.

With the student club, they focused on things like property rights, they talk about Marxism, they talk about evictions by the government, they talk about environmental issues, they talk about labor issues, and etc. So these kinds of clubs are very different from the regular student clubs in which people just play guitar, have fun, have events. It’s more like an abnormal student club.

Anyway, I think getting into university makes me feel like the world is not is good as I thought. When I was in junior high, my mom is always telling me—if you study, you will have a good life. It was very simple and normal, but it seemed that when I get to university and I joined the student club, I found out that…this world sucks. Like really sucks! It triggered me to want to participate more.

Catta Chou. Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Catta Chou. Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

So when I was at university, our club did a lot of things on campus. We demanded the school abolish curfew for the female dormitory, as there was a curfew for the female dormitory but not the male dormitory.

Then there were events like—our university wanted to demolish the sports area and demolish the dormitories to build a hospital. The hospital was for the surrounding area—the community—but it wasn’t for the students. And when students already don’t have enough places to stay but they’re demolishing all these dormitories, this doesn’t make sense. So we did a lot of those kinds of things on the campus. That’s how it started. And then after I graduated I continued to participate.

AC: Could you discuss the history of the establishment of the festival? Who have been involved in organizing it, and has the group of people organizing the festival changed throughout the years as well?

CC: Around 2010 and 2011, there were a couple of events about high technology workers who were committing suicide or being busted—union busted—in that industry. This kind of thing was happening both in Taiwan and also China.

So me, some of the friends from this club, and friends’ friends from other clubs and universities became a part of a group called Cold Blooded High Tech Youth (高科技冷血青年). It was a very small, minor group of young people highly concerned about the working conditions of workers in the high technology industry—making cell phones, laptops, that kind of stuff.

During that time, a Canadian union worker came and asked a member of Cold Blooded High Tech Youth if we wanted to do a labor film festival in Taiwan, because they were doing one in Canada as well as in the United States and England—this was the Canadian Labour International Film Festival. They had a network that reached many places.

So those who were working on this first film festival got the films from the Canadian Labour International Film Festival, who told them it would be free to use these films for a film festival in Taiwan. Then the Taiwan group simply did the subtitles, organized a place to screen the film, and that’s it. This was from 2011 to 2012.

AC: I see. If the idea and initial content were actually given to the Taiwanese organizers by the Canadian union members involved in a film festival. How did they know to contact you all, that is, how was the initial contact made?

CC: They actually contacted Lennon Wang. He was the former president of this organization, Youth Labor Union 95. At the time, he was working at a bank and was the general secretary of a bank union. Right now he is working at SPA, the Serve People Association. In Taoyuan they are doing migrant workers work.

He called himself an “international labor union activist.” He had a lot of contacts from different places and he also went to international meetings for union members, so he knows a lot of people.

AC: What was Youth Labor Union 95 about?

CC: It started from around 2004-2006. There were a group of young students who were very concerned about youth working rights, so they started from the minimum wage issues, especially those regarding hourly wage—because most young people get hourly wages. So they started from that, demanding 95 NTD per hour. Right now the minimum wage is 140 NTD per hour, so you can tell this movement already has a long history by now.

AC: And was this also in the tech industry?

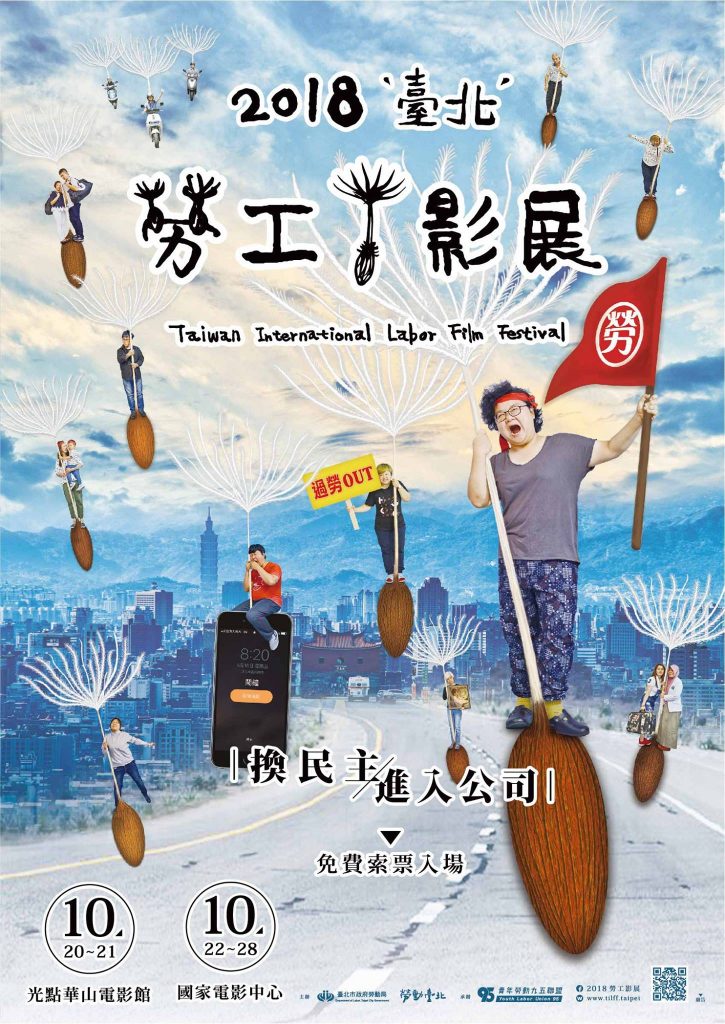

Poster for the film festival. Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Poster for the film festival. Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

CC: Not exactly. The Youth Labor Union was more about the service industry, because most young people go to restaurants to work. But the High Tech Cold Blooded Youth people, a couple of them were helping the union from a specific factory that was providing touch panels for HTC. A group of workers in the factory wanted to have a union, but before they got the union established, they started to get fired. Some of our friends who were helping the workers invited us together as a group to help the unions fight to get their rights back.

AC: The Cold Blooded Youth group was working in conjunction with the Youth Labor 95? Was there a relationship between these groups?

CC: In a way, they overlap with each other. I was a member of Youth Labor Union 95, but at the same time, I was also a part of the Cold Blooded Youth. It was like a network. The reason why I joined the Youth Labor Union is also because of networking. It started when some of the YLU95 came to our student club to talk about what they’re doing and invited us to join their project with other student clubs from different universities. And during our club’s summer camp and winter camp, we would come together from our different universities and talk about what we were doing and if there was anything we could do together.

AC: What was distinct about each groups’ mission or goal?

CC: I think Youth Labor Union had kind of a mission—like we wanted to talk about young people working. Cold Blooded was more like a temporary group, especially for the high-tech industry workers, because during that year—2010—there were so many things happening in Taiwan and also in China. People were starting to talk about the fact that “Apple is actually a sweatshop,” and that kind of stuff.

AC: So how did the film festival come out of this network?

CC: At the time, Cold Blooded Youth was doing a lot of actions and campaigns and protests. For example, we would go to the Apple store and HTC’s headquarters to protest. But it seems that the company doesn’t really care. So we wanted to shift discussion to talk more about the globalized sweatshop chain. But it’s really hard for students to talk about that kind of big theory—for example, how commodities come from Cambodia to China and then to Taiwan. So we were thinking, maybe we can use other ways to get people involved.

It was also about that time that Lennon, who was a part of Youth Labor Union 95, went to some other conferences and he met the Canadian union guys. They knew that in Taiwan, compared to other countries, the history of unions is pretty short and we need a lot of resources. So the Canadian people just said, “If you want to use the film, you can use the film.”

After he made the connection with the Canadian film festival people, Lennon brought up the idea to one of the members of High Tech Cold Blooded Youth, saying “hey, I think you guys should try this,” and so a member from Cold Blooded Youth eventually decided to put it into action.

AC: How do you feel like the film festival has transformed from its starting point till now?

CC: We started in 2011, and that was a very tiny international film festival. We started from Taipei and went around Taiwan to six to eight cities doing screenings.

But it was really small. Like we would do it in a coffee shop and it would be only 30 people or less. But we still did it. And after that in 2013, we also did an “Iron Horse Film Festival.” It was more an independent film festival about abnormal issues, like the anti-nuclear movement, neoliberalism, labor issues, evictions, that kind of thing. It was a very independent film festival. It has a long history, the Iron Horse Film Festival. In 2013, I was invited to join the group because they wanted to start up again. But then it stopped. It didn’t come back again.

Anyway, this experience made me think that film is actually a very good tool to talk to people with. Because they are forced to sit in there and look at the screen. And after they finish the film they might have a lot of questions or feedback, and so you can trigger them to have the motivation to learn more about this issue. This is also why I think the labor film festival is so important.

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Movies are usually entertainment, so you can just sit back and enjoy the stories. But labor films could either be a documentary about what really happened, or they could also be fiction. But the fiction could also be really inspiring.

But anyway, it’s something to get people to start talking about these issues. And I think it was important to make labor into a film festival theme. We already have “Women Make Waves”—it’s a film festival in Taipei about women’s issues. We also have documentary film festivals and the Taipei Film Festival, so we had a lot of film festivals with different themes. But we didn’t really have a labor film festival. That meant labor was not something people wanted to or were talking about. So when we made this a big event about labor issues, people start to think, “Oh this is something that we could talk about in our lives.”

AC: After the first few years, were there any big changes that were made to the festival? How did the festival then compare to now?

CC: In the recent years, from 2016 to 2018, I would say we are very lucky, partly because the commissioner of the Department of Labor of Taipei City Government is one of our people—she’s a unionist. She was working for one of the NGOs in Taipei, so she knows what we are doing and she trusts us.

The very first year, I already had all the films and the themes that I want to do, the only thing that I need is the funding. Then the Taipei City Government Labor Department came to us and said that this year they don’t want to do events they’ve done in previous years; instead, they want to have a labor film festival. So I was like, “Okay, I’ve already got a list and everything for you guys, I just need money.”

Then last year, because the government thought the first year of the labor film festival was really good, they also wanted to do the same thing. But last year I started to work at an environmental protection group, so I had a full-time job and I couldn’t really do the whole thing. But I still wanted to do the film festival, so I invited one of the friends I met during the Iron Horse Film Festival, and she became the curator. She did the events and made the theme. So last year was also very successful, luckily.

AC: How do you feel like this year’s festival is distinct from the past two years?

CC: The past two years we were talking about pinpointing what’s wrong with society. The first year we talked about the working poor and the working poor youth especially, and last year we were talking about overwork.

Every year we try to put in some of the positive parts, like telling people you should start a union, you should start to speak up, you should start to learn about your rights, those kinds of things. But for me, it seems that forming a union is not the only solution. At least after these two years, I’ve been thinking that there shouldn’t be only one solution. It shouldn’t be only about forming unions.

Starting from this year, I started to think about how can we really change the struggle for workers? And then I do some research and I found out that cooperatives are very popular in many western countries—but not in Taiwan. I wanted to dig up more. So I went on to do research on the cooperative laws in Taiwan and the history of other countries, like with Mondragon in Spain, or examples from the United States, England, and other places. I found out that the point is actually not the form of the organization—it could be a union, it could be cooperation, it could be a corporation, it could be anything—the point is that everyone has to have the ability to participate in the organization.

To put simply, it is cooperative work. In this cooperation, it’s one person one vote. That’s what’s fair. But in most of the companies or in most organizations, it’s not like that. So it’s not about the form of the organization, but whether you have the rights to participate. This is also why this year the topic is “Let Democracy into the Company.”

The union is also one of the ways to participate in the company. ‘Cause you have the voices of a lot of people from the collective who are able to talk to the company and demand fairer working conditions, pay, etc. It’s a way to achieve democracy—or to at least a way to participate in the company.

But it’s not the only way to do that. In one of the films, it says that usually when we think about employment, it’s usually money employing people to work. But can’t we have it the opposite way, with workers employing the money to work for them? ‘Cause when you are working for the money, that means money can decide what you can do or what you cannot do. But if you make it the opposite way—workers being able to employ their money—then workers have the rights to decide what their money can do.

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

AC: How do you think this film festival is especially relevant within the context of current labor issues or the current status of labor moments in Taiwan? What about globally?

CC: I think for Taiwan, these three years, I’ve been trying to provide some of the materials for people to start imagining. Because the union history in Taiwan is really, really short. It’s super short compared to other countries. A lot of times we can’t really imagine what can workers do, or what can unions do.

In a way, all of these films—because they are mostly from Western countries or other foreign countries—are actually importing some examples from abroad. When you see them, you know people out there, they’re doing things like this. This is material for people in Taiwan to think about what we can do in Taiwan.

Because a lot of times we are still in that frame—unions can only do this and that, and workers can only join a union or eat yourself, that’s it. We want to break down this frame and say that there are actually a lot of things you can do—you just need to use your imagination. And if you can’t imagine, then the film festival can give you some materials, food for thought.

AC: Is there anything specifically about the content for the films that you think is worth mentioning? Maybe you could pick a certain film that spoke to you the most and talk about it a little.

CC: The opening film is called “Can We Do It Ourselves?”. It discusses whether workers can actually have their own company, rather than having a boss or a board to decide what they can do. For me, that film was really a huge shock, because I never thought about that before.

The film director put out the question, why do we think democracy in politics is good and normal, but we don’t think that democracy in the workplace is normal. So that’s weird. Like, why is that? How can we accept that we have to vote every couple years to decide the president, but we cannot vote or have a say in our workplace? This is something that really shocked me. I had never thought about it before.

I think it’s really important for people to have the mindset that you are not always the one being manipulated by capitalism or by the company—you have your own will and you can do things you want. From my personal experience, many of my friends or people my age think, “This salary is really bad and I want to go somewhere else.” But other companies have the same bad salaries too, so it becomes a vicious cycle and it never ends.

You start from this company but it sucks so you go to the next one. And the next one still sucks so you go to the next, next one. Is it possible for us to actually stand up and change this kind of situation? Or else we are just the same as Japan or Korea, where young people are so desperate they just give up everything, they don’t want to get married, they don’t want to give birth—they don’t want to think about their future because they have no future at all. The film for me is not only food for thought, but it’s also a big push—it sums up something we should start to think about, regarding how we can change these kinds of labor situations.

AC: Is there a way you think viewers can approach watching or thinking about the films this year that are from the west versus films from the Global South/Third World nations?

CC: I have to say that the films I brought in are mostly from the States or Europe or England somewhere, so it is a very western or white-ish point of view. To be honest, I’m not a very artistic person; I don’t really watch a lot of films. For me, I just use these films as a tool to talk about stories and issues.

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

This year we have fifteen films from eleven countries or areas. Trying to be diverse in a way. But still, we have to be honest—it’s mostly western ideology. A couple years ago when I went to Australia, a lot of Australian activist friends were asking, “Do you support Lenin, do you support Marxism?” and I had no idea, because I had never really read this kind of theory, so I didn’t really put myself in any of these categories.

That was a little confusing for me, because it was as if I don’t belong to any of these groups. It made me feel weird when I was in Australia. But when I came back, I found out most people in Taiwan don’t have this ideology in their mind. They only have one thought—to feed yourself today, maybe think about tomorrow, and that’s it. People don’t really think about what they can do or what they should have to do.

So it’s more about imagination. It’s hard to know that there’s any other possibilities to make any change. With the films, I have to admit that it’s a western point of view, but even so, I think it’s a good place for people to start thinking.

This year the non-western films, there’s only three of them. One is about migrant workers in Macau, the other is workers in Japan, and the other is migrant workers in Taiwan.

AC: What was the process of finding films and collaborating with international filmmakers like? Have you found that any of these connections continue into the future?

CC: I, right now, still get emails or messages from film directors we had worked with in 2013 during the Iron Horse Film Festival. So there are some lasting connections. For example, last year we had Shiho, a Japanese film director, come to Taiwan and chat with us, and apart from that we still have a lot of contacts that have built up over the years. Most of the time, though, I make more contact with the labor film organizers than the film directors.

AC: Did you come across any difficulties or hardships while organizing this year?

CC: There’s always a big thing that takes a lot of time—doing the subtitling. Because in most of these western films, they are speaking in English and they talk really really fast.

When you are doing subtitling, one thing is you have to do is match up the speaking, but the other thing is that there is so much context within their speech. Most times, directly translating the words doesn’t really make sense. So every time we do these kinds of new films from other countries, we have to make extra efforts on introducing the background and the context of the film.

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

Photo credit: Taiwan International Labor Film Festival

AC: Lastly, do you have any last words to say to our readers both in Taiwan and also internationally?

CC: If you’re in Taiwan, please do come, and if you’re not in Taiwan, you should organize one in the place where you are.