by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Free Chinese Feminists/Facebook

THE #METOO campaign has exploded across the Chinese Internet in the past month. This was prompted by an outpouring of anger regarding a twenty-year-old sexual assault case involving university student Gao Yan, who killed herself in 1998 following an alleged rape by university professor Shen Yang. The case took place when Gao was a nineteen-year-old sophomore studying literature at Peking University and when Shen was forty years old. In particular, Gao’s former classmates claim that Shen dated and had sexual relationships with other students during this time and that Shen subsequently spread rumors about Gao, claiming that she had seduced him.

Anger spread rapidly across the Chinese Internet following remembrances posted by friends of Gao commemorating the twenty year anniversary of her death on Tomb Sweeping Day this year, when Chinese traditionally commemorate the dead.

Anger against Shen Yang, with Gao’s story being shared millions of times online, eventually led Nanjing University, where Shen currently teaches, to terminate Shen’s contract. Shen has been condemned by a number of universities and Peking University has vowed to do more about sexual harassment in the future. An open letter calling attention to the issue of sexual harassment has also been signed by professors from over 30 university and students and alumni from 50 universities. Shen, however, continues to defend himself, claiming that Gao was mentally ill, having remained quite vocal on the issue through the years.

Photo of Gao Yan when she was alive

Photo of Gao Yan when she was alive

Another former student of Shen’s, Xu Hongyun, has also come forward to allege sexual assault by Shen when considering Shen for her Ph. D advisor, stating that this contributed to her decision not to pursue further graduate studies. This was, however, deleted by state censors. A document has also emerged purporting to be Peking University’s report on Gao’s suicide, stating that Shen was not guilty for Gao’s death, claiming that Gao was mentally ill, and ordering Shen to only make an apology.

Li Youyou, one of Gao’s friends who posted a widely circulated essay commemorating Gao, has stated that four other victims of sexual assault by Shen have approached her. Current Peking University students have organized to call on the administration to make the full matters of the case public, following an essay published by a current Peking University student, Deng Yuhao, which has led to confrontations between Peking University students and administrators.

This is not the first time in past months that anger from Chinese netizens has called for action against Chinese academics guilty of past incidents of sexual assault. In January, outrage broke out following an essay posted online by Luo Xixi, a former Beihang University student, alleging an attempted rape by her former advisor, Chen Xiaowu. This led to a number of online petitions, including a petition signed started by a professor at Wuhan University, Xu Kaibin, which 50 academics from 30 universities signed, and a petition urging Fudan University to adopt anti-sexual harassment policies which gained 300 signatories before being deleted. Preceding this, in 2014, 256 professors signed a petition urging universities to adopt sexual harassment policies.

In particular, sexual harassment policies have been slow to catch on in China. Although the Chinese government has touted gender equality going back to the Mao period, actually existing social conditions make it clear that patriarchy remains deeply entrenched in China. The concept of sexual harassment has been slow to be introduced into law, the term sexual harassment only being introduced into law in 2005 but remaining vague in terms of definition after China’s first sexual harassment case was dismissed in 2001.

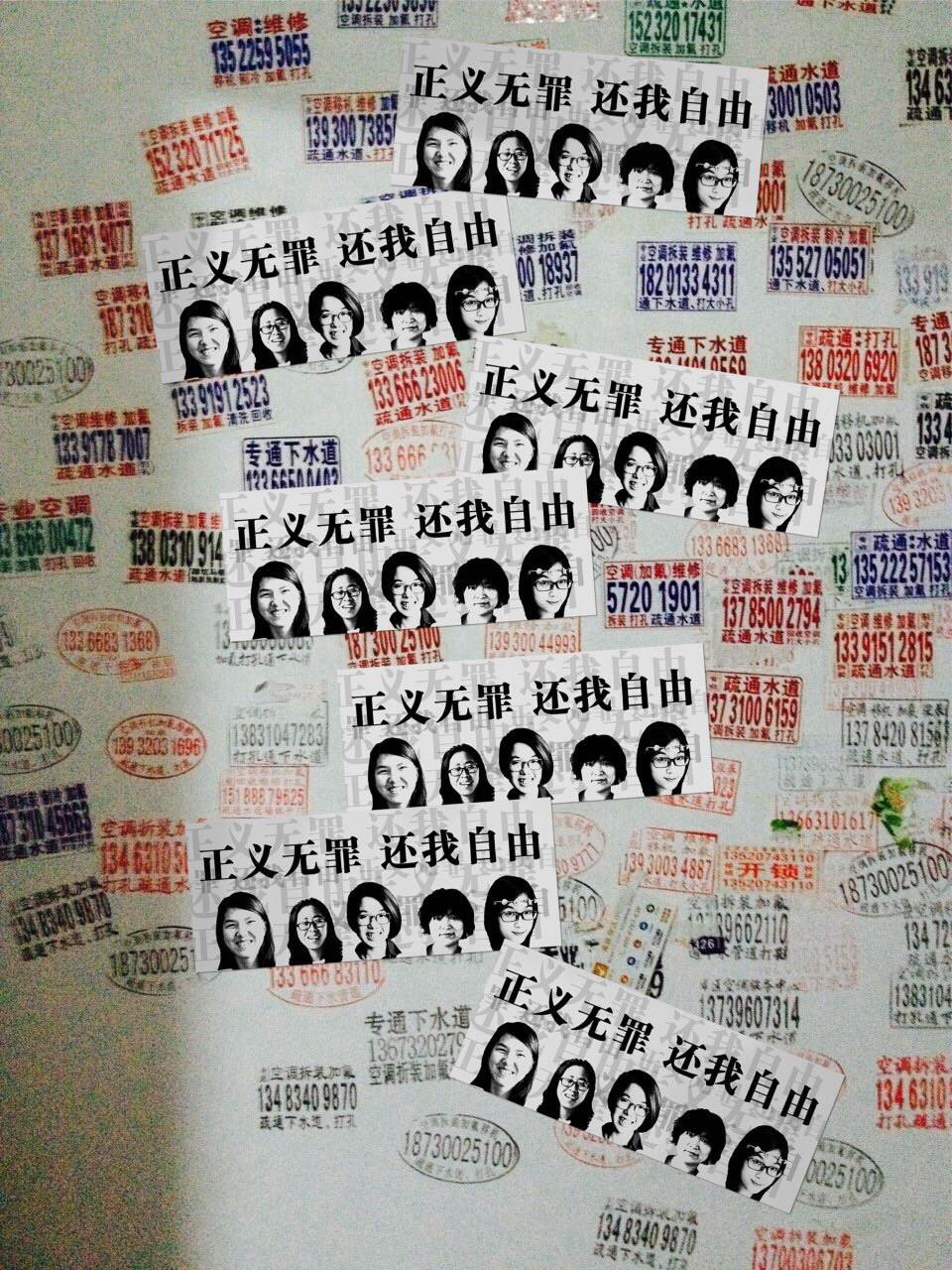

Posters calling for the release of the Feminist Five in 2015. Photo credit: Free Chinese Feminists/Facebook

Posters calling for the release of the Feminist Five in 2015. Photo credit: Free Chinese Feminists/Facebook

Similarly, the authorities have frequently reacted against anti-sexual harassment campaigns. Last year, during the wave of outrage following Luo Xixi’s online essay, students that organized against sexual harassment were called in for disciplining by their universities in at least ten cases. Action taken against anti-sexual harassment activists would be an ongoing issue. China’s most famous case of anti-sexual harassment activists being punished would be the “Feminist Five”, who were arrested by Chinese authorities in 2015 for an anti-sexual harassment campaign on public transportation. A similar incident would occur in Guangzhou with feminist activist Zhang Leilei attempting to crowdfund an anti-sexual harassment campaign before she was eventually asked to leave Guangzhou by local authorities.

What is unique about current outrage is how much of it is centered through online campaigns. Taking inspiration from the #MeToo phenonenon in the West, Chinese victims of sexual harassment and assault are now taking to the Internet to share their stories. Give that authorities are rapidly taking down stories of sexual harassment for fear that this will lead to social unrest, sometimes this employs codewords to get around censoring algorithms, sharing screenshots of articles to make it more difficult for text-based censorship, or using networks of websites with the expectation of their being taken down. Dozens of stories are posted daily on the website, “Walls and Books”, for example.

Although Chinese state-run media has sometimes acknowledged the problem, as seen in sympathetic editorials earlier this year in state-run media outlets. At other times, state-run media has seen fit to deny in a nationalistic manner that sexual harassment is a problem which occurs in China, claiming that this only takes place within the West. And Internet censorship of stories of sexual harassment and assault shared online has been ongoing. Attempts have also been made by Chinese authorities to crack down on Chinese feminist media outlets this year, including the closure of China’s largest feminist website, Feminist Voices, the likely cause being for reporting on the Women’s March in the United States. Adding insult to injury, this closure took place on International Women’s Day this year.

Namely, the Chinese state fears dissent and social unrest in any form, including from outrage over sexual harassment and assaults in universities. After all, while outrage has remained confined to universities, seen as privileged bastions of learning in China, the possibility for outrage to expand in scope is large. Misogynistic attitudes remain entrenched in society, as observed in social criticism against unmarried “leftover women” and demeaning views about “leftover women” expressed by state-run women’s organizations in the past.

Photo credit: Free Chinese Feminists/Facebook

Photo credit: Free Chinese Feminists/Facebook

Online anger against Chinese government actions has broken out in several notable incidents in the past year. Outrage has taken place regarding mass evictions of migrant workers in Beijing and a sexual molestation scandal involving a kindergarten with ties to military officials, for example. And while these were individuals issues that were not directly critical of the Chinese government writ large, the wave of shock following moves by Chinese president Xi Jinping towards lifting the term limits that a Chinese president can serve, led to campaigns criticizing Xi to break out among overseas Chinese students.

Whatever the restrictions that the Chinese government may seek to impose on Chinese netizens’ access to the outside world, China is sufficiently connected to the international world through the Internet that online campaigns such as the #MeToo movement reverberate in China. However, the Chinese government generally reacts badly against any form of social unrest. Because of its partial inspiration from the western phenomenon of #MeToo, the Chinese government, for example, may construe the present campaign in connection with western attempts to undermine China, much as it did western support for the Feminist Five.

As such, how the Chinese government reacts to the wave of anger regarding deep-rooted problems of sexual assault going forward remains to be seen. And it remains to be seen whether netizens will eventually have to move activity online off of the Internet and move towards real-world actions. Netizens simply continue to post articles at a rate faster than the Chinese government can censor, but the trend shows no sign of stopping and outrage shows no sign of abating, at least for the time being. Has the genie has finally been let out of the bottle.