by Garrett Dee

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Star Trek: Beyond

THE ISSUE OF the misrepresentation of people of Asian descent in Hollywood came to even larger mainstream attention earlier this year as a result of the crude, stereotypical jokes utilized by hosts Chris Rock and Sacha Baron Cohen at this year’s Academy Awards ceremony. Despite the fact that this year’s Oscars had already come under intense criticism as a result of its lack of diversity (all of the nominees for Best Actor and Best Actress this year were white actors), the presenters of the night thought it appropriate to use unwitting Asian children as human props in an effort to make a distasteful joke that stereotypically caricatured them as alternatively accountants or child laborers. The use of the “Asians-as-nerds” trope has been a running gag in Hollywood for years and has gone mostly unnoticed as a display of open racism in the American film industry; it would seem that most audiences seem to buy too much into the model minority myth to believe that Asian-American actors would be anything but “in on the joke” as well.

The poor taste of the humor was not lost on those members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences of Asian descent, two dozen of whom sent an open letter to the academy demanding an apology for the night’s events. Amongst those signatory to the letter were famed Taiwanese director Ang Lee (李安), himself a two time Academy Award winner, and Japanese-American actor and activist George Takei. Academy chief executive Dawn Hudson responded with an underwhelming, curt letter which sounded more like an automatically-generated response than a sincere apology for allowing such a blatantly racist comedic set to pass through the censors and make its way onto one of the most-viewed awards shows in the United States. The controversy over the #OscarsSoWhite debacle serves as a backdrop to make the slight even more egregious, as the entire night was already deeply shrouded by the institutionalized racism of the Hollywood film industry. The entire event sent a message that racism against persons of Asian descent is not yet collectively considered to be of the same severity as racism against other POC groups.

New Faces Advocating for Better Representation of Asian Men and Women in Film

IN SPITE OF these sorts of setbacks, there does remain reason to hope that the prevailing notions governing these sorts of problematic film practices will start being chipped away. Famed for her portrayal of the matron of the Huang family in ABC’s sitcom Fresh Off the Boat, based of the memoirs of Taiwanese-American author and TV personality Eddy Huang, Taiwanese-American actress Constance Wu has emerged as a strong advocate for better representation of people in Asian descent in Hollywood and an outspoken critic against the erasure of their stories. The actress has been quite up front and vocal in her criticisms of the way that Asian stories in mainstream entertainment are often pigeonholed to a limited collection of worn-out tropes. She bemoans the lack of opportunity that actors of Asian descent face in casting processes where the character is slated for a person with a white face, as well as the casting of white actors in roles that would have been more fittingly portrayed by a person of color. Following her excoriation of the exploration of CGI technology aimed at making actress Scarlett Johansson appear more Asian in the film reboot of the popular Japanese manga Ghost in the Shell as modern day yellowface, Wu recently posted a scathing opinion to her Twitter account of the casting of Matt Damon as a hero who saves China from invading dragons in the upcoming Great Wall film. In the case of that film, itself a joint Chinese-American production under the auspices of the Chinese Wanda group and not a Hollywood venture, this is an example of how pervasive these sorts of attitudes can be even in the Asian film world.

Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi (left) and Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One (right). Both roles were originally written as Asian, but cast white actors. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell and Dr. Strange

Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi (left) and Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One (right). Both roles were originally written as Asian, but cast white actors. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell and Dr. Strange

Wu is not the only one remarking about the ubiquity of casting white actors in these sorts of roles, though, and fans have put forth strong backlash against the decisions to cast white actors in roles originally written as Asian in Ghost in the Shell as well as other popular franchises such as Dr. Strange and Avatar: The Last Airbender. In each case the rationale behind the casting was given as a belief that actors of Asian descent would not be able to draw as large of an audience as bigger name white actors. While there may be a kernel of truth to the idea that audiences will display a greater willingness to shell out their paychecks on movie tickets when the movie in question features a well-known international star, this is certainly not an infallible cinematic principle written in proverbial stone, as evidenced by last year’s major box office flop Gods of Egypt in which the pantheon of Egyptian gods was reimagined as a cast of mostly white actors to dismal effect. As Wu herself point outs, even if their films turn out to be box offices crashes, actors of color should be given the same opportunity to crash as any other practitioner of the craft.

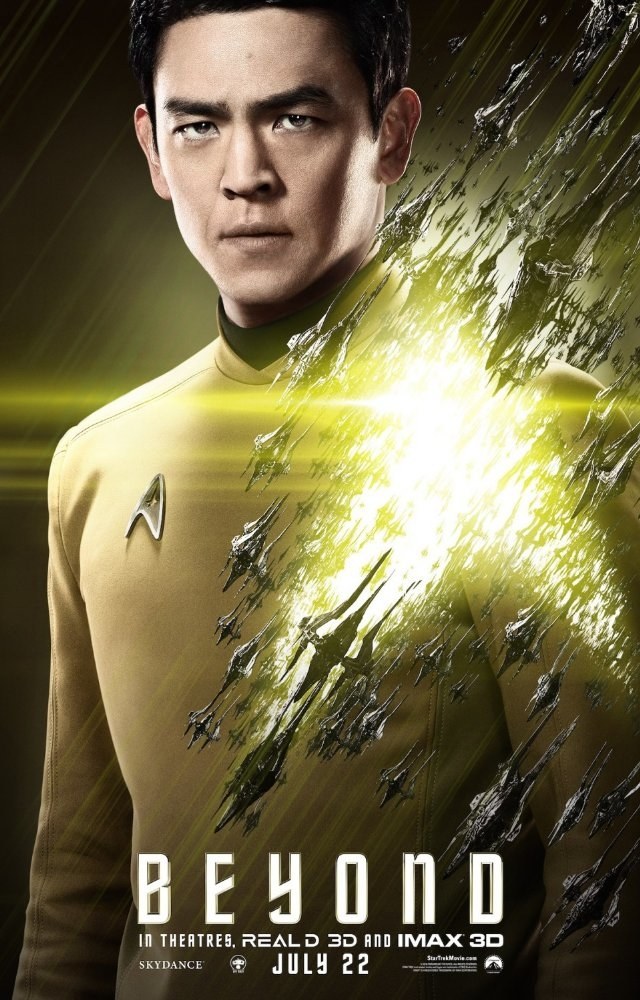

On the other hand, it seems that it doesn’t require direction from above to get audiences to notice the lack of actors of Asian descent in meaningful film and TV roles. A viral campaign styling itself #StarringJohnCho recently emerged centered around Korean-American actor John Cho, who is currently considered one of the most well-recognized Asian-American male actors in Hollywood (a similar campaign, #StarringConstanceWu, arose around Wu shortly after). The campaign, whose purpose was to point out the lack of Asian-American male leading roles (especially those involving a romantic partner), superimposed Cho’s face onto the body of the male lead on the posters of popular films in an effort to highlight the lack of such roles in the actual film industry.

Like Wu, Cho has spoken frankly about race and his struggle with discrimination as an actor of Asian descent in the US film industry, and his own difficulties with finding roles that portray his characters in a fully human light. Cho had already broken ground in his portrayal of the leading-man romantic role opposite a white leading actress in the prematurely-cancelled ABC series Selfie, though he also admits that he experienced racism during the production of the series. Whereas Asian women on screen are often fetishized and portrayed in a dull, exaggeratedly-sexual context, Asian men face the opposite problem of being aggressively desexualized and made undesirable to the point where onscreen Asian male sexuality is viewed as almost taboo, particularly when the pairing is with a woman of a different race. One is reminded of the awkwardly platonic embrace between Jet Li and Aaliyah at the end of the 2000 action flick Romeo Must Die, originally written as a kiss which was then removed when audiences expressed their discomfort at seeing an Asian male portrayed in a romantic capacity.

A common theme in both Wu and Cho’s takedowns of common Hollywood casting practices is the lack of character depth given to Asian roles in films meant for mainstream audiences. In lamenting that until recently, normally human experiences like doing taxes or picking out Halloween costumes have been considered as exclusively white experiences, Wu points out the ugly effects that essentialism has on storytelling techniques in Hollywood. While white characters are given meaningful, evocative roles that allow them to traverse the depths of the human experience on screen, actors of Asian descent are usually tied to stories considered to have some kind of essentially Asian theme to them, despite the fact that many of these stories are in fact based more on stereotype than on actual Asian-American narratives. The fact that Long Duk Dong of Sixteen Candles infamy or Ken Jeong’s turn as Mr. Chow in the Hangover series are among the most memorable Asian performances in popular US consciousness is testament to the dismal lack of authenticity in roles given to Asian-American actors.

Sulu’s Sexuality and Opening a Dialogue for the Future of Gay Asian Visibility

CHO REACHES peak visibility in his most recent turn as Commander Sulu in the popular film reboot of the much beloved Star Trek series, the latest installation of which, Star Trek: Beyond, was released last month. The original TV show itself was know for being boundary-pushing on issues of race, casting an African-American actress and Japanese-American actor in lead roles at a time when US audiences were unaccustomed to viewing multiracial casts. Gene Roddenberry, creator of the original series, intentionally steered away from tokenism in the portrayal of Sulu’s character despite heavy misgivings at the time about casting an Asian actor in a lead role, and actor George Takei was known for heavily lobbying the writers on behalf of a more prominent role for his character. The end result of this effort culminated in an iconic Asian television character fondly remembered by fans for his fencing swordplay and sense of adventure whose role expanded steadily throughout the show’s decades-long run, at one point taking over command of the crew while William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy’s respective characters were indisposed.

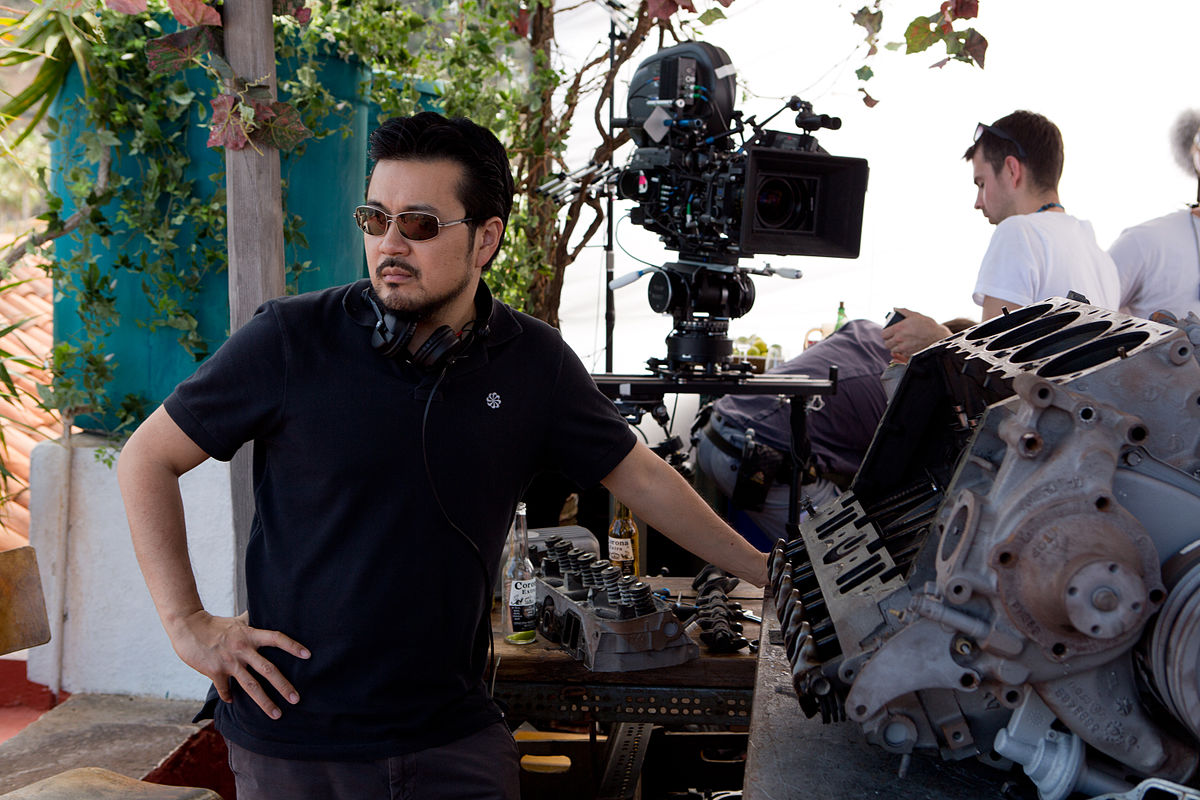

It is the decision of the production team of the latest Star Trek movie to reimagine the newest iteration of the Sulu character has having a husband that has opened the door to a larger and more mainstream discussion on intersectionality and both Asian and LGBTQ visibility in popular cinema. The decision was made as a tribute to Takei, who portrayed the character as heterosexual whilst remaining a closeted actor during the production of the original series. The final decision was communicated to Cho directly from the film’s Taiwanese-American director Justin Lin (林詣彬), and early on in the production Cho specifically requested that the role of Sulu’s husband be portrayed by an Asian actor in a deliberate attempt to personify a romantic relationship between two Asian men, rarely acknowledged either on the silver screen or (as Cho duly notes) in the mainstream US LGBTQ community, in a film assured to reach a huge worldwide audience.

Justin Lin. Photo credit: Joshua Henson/WikiCommons

Justin Lin. Photo credit: Joshua Henson/WikiCommons

The feminization of Asian men in popular culture is particularly troublesome for gay men of Asian descent, who already deal with the heterosexist notion that gay men are inherently feminine and have little value in a society dominated by masculinity. Cho himself betrayed a bit of this style of thinking in his concern that his role would spark backlash in the Asian-American community as continuing the idea that Asian men are fundamentally effeminate, though he later stated that he had come to terms with these doubts and embraced the character’s sexuality.

In the same manner that a young John Cho growing up the son of a Korean immigrant in Houston was admittedly inspired to be an actor through seeing George Takei light up his TV screen, his work in this film has the potential to influence young gay men of Asian descent who currently lack much in the way of role models. Though films like Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet (喜宴), or the more recent Taiwanese-produced Baby Steps (滿月酒), which is set partially in the US, offer up a realistic take on their respective gay Asian characters, they still focus heavily on familial coming out issues and portray the Asian male lead as looking to white America for their ultimate source of self-acceptance. For those of Asian descent growing up gay in the United States like comedian Joel Kim Booster (whose insightful and humorous take on identity can be found here), meaningful representations of their intersecting identities can be nearly impossible to find and being gay can sometimes seem like an exclusively white experience, as Takei himself has admitted was the case during his years as an actor in Los Angeles. Seeing a gay Asian character who isn’t constantly dealing with overwhelming shame and cultural conflict starring in a traditionally masculine action hero role sends a different sort of message.

Justin Cho as Sulu. Photo credit: Star Trek Beyond

Justin Cho as Sulu. Photo credit: Star Trek Beyond

A common plot device utilized in a large number of action films which feature the imminent threat of some world-ending catastrophe is to have the stakes humanized by leaving one of the main casts’ loved ones squarely in the crossfires of the impending Armageddon. The fact that in Star Trek: Beyond this emotional crux of the film is realized with the Asian husband and daughter of an Asian male action star is a step in the right direction for greater authenticity in the representation of LGBTQ Asians and people of Asian descent in general. It would be superb for these roles to be expanded to the point where they could headline future films themselves instead of remaining supporting characters. One can hope that the casting of John Cho—himself the center of an online viral campaign to cast more Asian men in leading roles—in this part means that we are moving beyond the point where actors of Asian descent in Hollywood can only portray math whizzes, ancient kung fu masters, or tiger moms to the point where they can be swashbuckling gay space captains or Melrose Place-loving suburban housewives or just anything else any other actor gets to be.