by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Ghost in the Shell

“In the near future—corporate networks reach out to the stars. Electrons and light flow throughout the universe. The advance of computerisation, however, has not yet wiped out nations and ethnic groups.”

SO READS THE opening text of Mamoru Oshii’s original 1995 Ghost in the Shell animation. But this point seems to have escaped the 2017 Hollywood live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell directed by Rupert Sanders. In the last year, the movie has provoked massive outrage over its casting of Scarlett Johansson as the lead role of the film, the Major, who has been the protagonist of all iterations of the Ghost in the Shell franchise.

This was a move Asian-Americans and others criticized as “whitewashing” with the view that the role of the Major, a Japanese character in the original, should have gone to an Asian actor rather than a white one. Making matters worse were reports that the film’s producers were exploring ways to make Scarlett Johansson’s features appear more Asian-looking for the film. And so, rather ironically, it seems like the producers of the live action adaptation have rather failed to get a point which the original movie obliquely posits within the first frame for its far-flung future setting. No, we do not live in a society in which a white actor can be cast in a role which should go to an Asian actor and this will pass by without remark. In fact, irony of ironies, outrage over the matter primarily took place on the Internet.

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

The poor box office performance of the 2017 live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell can rightly be attributed to Asian-American outrage over the film’s whitewashing. Namely, the film is in fact a highly competent Hollywood production. One would have actually expected it to have done well in the box office and, in fact, pleased many of the fans of the original franchise, had it not drawn such controversy over “whitewashing” in its casting. If, unsurprisingly, it removes anything in the way of the artistry and philosophical depth which was present in the anime and manga forms of Ghost in the Shell, as with Akira and many other iconic anime released in America in the 1990s, one generally suspects that many fans of the original Ghost in the Shell anime were less interested in the franchise’s highly intellectual philosophical underpinnings than in its stylized action scenes and exotic Asian setting.

And so Asian-Americans are not giving themselves too much credit in suggesting that the whitewashing controversy was what led to Ghost in the Shell’s poor performance in theaters. Nevertheless, what the live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell ultimately illustrates is the almost comic degree to which Hollywood has failed to grapple with the controversy regarding whitewashing. What seem like possible attempts to address criticisms of whitewashing in the film, in fact, only reinforce accusations of whitewashing to an unbelievable level of ludicrousness. One even finds oneself wondering, how is it possible that Hollywood could be so blind about racial issues in 2017?

A Competent Hollywood Production And One Which Likely Would Have Been Commercially Successful, If Not For The Whitewashing Controversy

WHAT STRIKES as impressive about Hollywood’s adaptation of Ghost in the Shell is its beautiful imagery and excellent special effects, respectable soundtrack, and the many visual references to different iterations of the franchise it manages to stuff into two hours. All in all, for a Hollywood film, it is not a badly produced film, and one really would expect it to perform well at the box office if not for its run at the theaters being marred by controversy.

Of course, Ghost in the Shell was never a Hollywood action franchise to begin with. What is lost in the adaptation is any semblance of deeper philosophical thought present in the film, television series, and manga iterations of the franchise. The artistic use of ambiguity in the two Ghost in the Shell films directed by Mamoru Oshii which the live action adaptation primarily draws from is also wholly erased.

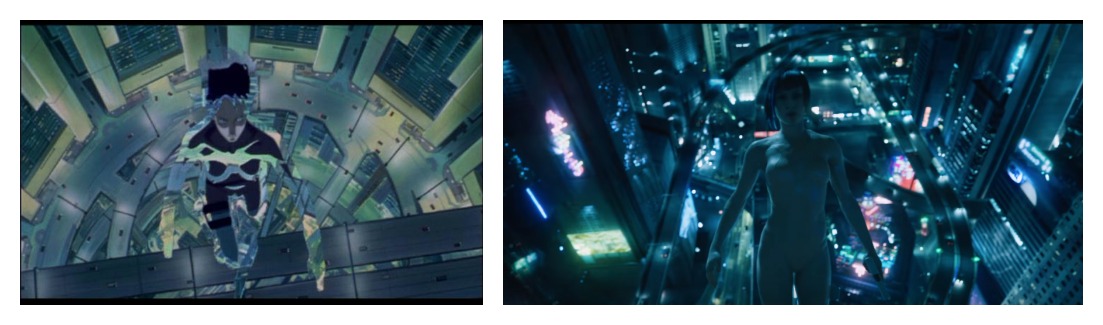

Visual comparison between the famous “jump scene” in the 1995 Ghost in the Shell animated film (left) and the live action adaptation (right)

Visual comparison between the famous “jump scene” in the 1995 Ghost in the Shell animated film (left) and the live action adaptation (right)

To the film’s credit, references abound in the live action adaptation to not only all versions of the franchise, but to Oshii’s storied career. The first Ghost in the Shell animated film is the most iconic and most highly recognizable iteration of the franchise. Moments from the first film are replicated such as the jump from a high-rise building by the Major while cloaked in thermo-optic camouflage or the climactic battle with a robotic tank near the end of the film. The visual language of second Ghost in the Shell film and its baroque depiction of a neon lit Internet in orange tones seems to be the primary reference point of the Internet in the live action adaptation. Scenes from both the first and second Ghost in the Shell animated films are recreated shot by shot, as well as some settings, such as Aramaki’s office

Plot elements are drawn liberally from not only the film, but also the Stand Alone Complex television series, with the use of Kuze. Another character visually references the second Ghost in the Shell animated film’s character Haraway. Surprisingly, visual references to even the most recent Ghost in the Shell OVA series, Arise, appear with regard to the style of motorcycle that the Major is seen riding in the film.

And references to Oshii’s oeuvre appear in the inclusion of Oshii’s signature basset hound—even named Gabriel, after the director’s real-life basset hound—and visual references to as obscure entries in Oshii’s catalogue as his forgotten masterpiece, the 2001 live-action Polish-Japanese co-production, Avalon, which some have suggested is in a way Oshii’s own attempt at a live-action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. Nevertheless, that the live action Ghost in the Shell can in some cases replicate imagery directly taken from the original does not merely evidence attention to detail, but are also a testament to the staying power of the visual imagery of the original Ghost in the Shell over two decades on.

It is a rather strange element that the live action adaptation backs away entirely from Kenji Kawai’s iconic, haunting soundtrack, using Kawai’s theme only as a leitmotif for the ending credits in, bizarrely enough, a Steve Aoki remix. The film also backs away from the heavy employment of the montage and atmospheric music characteristic of Oshii films, instead relying on intrusive and loud Hollywood special effects. But though verging from the source material, the soundtrack is not a bad one, if sounding a bit more like Blade Runner’s soundtrack than like Ghost in the Shell’s soundtrack.

Comparison between the cityscape between the 1995 Ghost in the Shell animated film (left) and the live action version (right). The 1995 animated film notably features a much more realistic urban landscape, whereas the live action film draws heavily from the depiction of San Francisco in Blade Runner

Comparison between the cityscape between the 1995 Ghost in the Shell animated film (left) and the live action version (right). The 1995 animated film notably features a much more realistic urban landscape, whereas the live action film draws heavily from the depiction of San Francisco in Blade Runner

The setting of the live action film is based on Hong Kong. The original animated film’s setting shows its heavy influences by Hong Kong’s urban aesthetics. Yet the aesthetics of the Hong Kong-esque setting in the live action adaptation seem much more drawn from Blade Runner, in fact, rather than the urban landscape of any version of Ghost in the Shell.

Stylistically, the film is also a largely a linear narrative with a straightforward beginning, middle, and end, whereas Oshii’s stylistics orient strongly towards drawing the viewer’s interest in at the start of the film by beginning in media res and then dosing the viewer with a large amount of exposition all at once. Notably, the live action adaptation also operates at the “macro-level” in that it attempts a rather complete exploration of its setting, while Oshii’s two animated Ghost in the Shell films are content to pose themselves as “micro-level” stories set at the ground level in a larger setting which is never fully explained.

But, again, one generally suspects that many fans of the original anime were less interested in the franchise’s highly intellectual philosophical underpinnings than in its stylized action scenes and exotic Asian setting. So one generally suspects that the live action would have been well-received by many if not marred by controversy. Overall, the film is a quite firmly a competent Hollywood production.

Tone Deaf Attempts To Avoid Racial Controversy in The Live Action Adaptation

AND SO AS the source of much controversy, we might hone in on the issue of race in the live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. In particular, the film evidences the strong possibility of late changes made to the film in order to address accusations of “whitewashing”. What this evidences is that, no, Hollywood does not still get whitewashing and that this problem is even worse than anyone imagined.

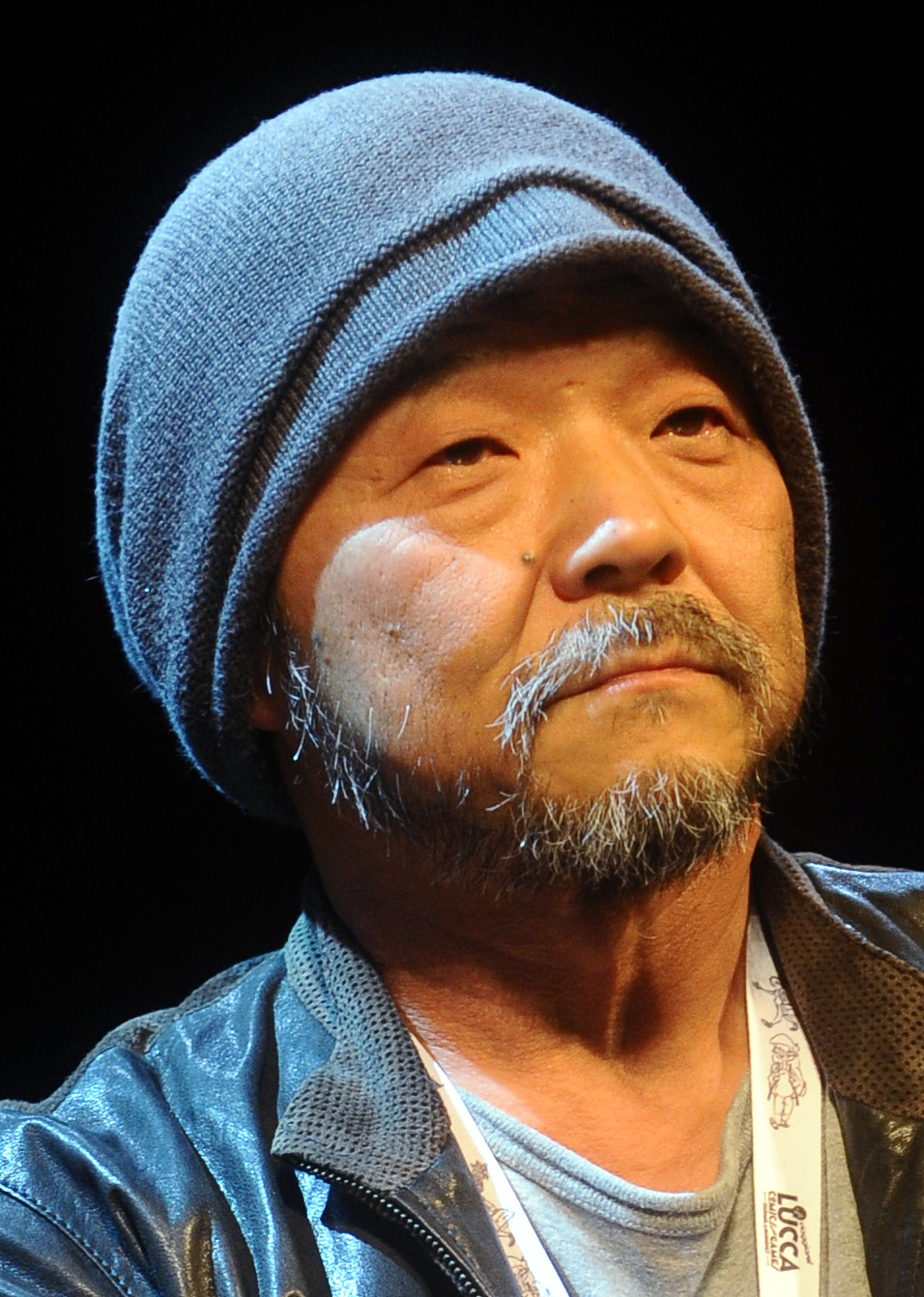

Following accusations, Hollywood has been evasive about the issue throughout. Hollywood at times has seen fit to trot out original director Mamoru Oshii himself to defend the live action adaptation against charges of whitewashing. Obviously Oshii is an Asian man, but Oshii has been less than critical of the Hollywood adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, commenting that he felt Johansson’s casting was apt, and that he felt the controversy was overblown. Yet it is not too surprising that Oshii might not jump onboard with criticisms of Ghost in the Shell on the basis of its whitewashing. Racial dynamics in Asia are not the same as racial dynamics in America. It is not too surprising that the problem might fly by Oshii, as a result.

Mamoru Oshii. Photo credit: Niccolò Caranti/CC

Mamoru Oshii. Photo credit: Niccolò Caranti/CC

Nonetheless, regarding broader questions about adaptation, we may note that setting of the original Ghost in the Shell is always Japan and all characters are presumably Japanese. Even if the setting draws greatly from locations outside Japan, such as Hong Kong or China, and in the iterations of the franchise as the original 1995 Ghost in the Shell animation, Motoko Kusanagi sometimes has non-Asian features such as blue eyes, there is never any real suggestion that the characters are not Japanese despite that they might have some seemingly non-Asian features.

Anime characters oftentimes have distinctively non-Asian features, despite the fact that there is no implication that they are not Japanese or not Asian. Sailor Moon may be the most famous example of this phenomenon, as while uniformly depicted as being a Japanese schoolgirl, she clearly has blonde hair and blue eyes. This use of non-Asian features in the depiction of Asian characters generally is primarily for the sake of greater variation among character designs, to make characters more easily recognizable from each other than if they all had black hair and brown eyes. Some have attempted to defend the film in line with this commonplace practice in anime, but one does well to remember that the visual language of live-action films and animation are not the same by nature of the intrinsic differences between the two mediums and so this is no real defense.

Unsurprisingly, some have also used Ghost in the Shell’s setting as a defense of the movie, since its futuristic setting could mean that it may take place in some “post-racial” version of Japan. The live action adaptation is ambiguous about which country it takes place in, although this would be a country with a “prime minister” instead of a president, much like Japan. A number of characters are clearly Asian, particularly with Togusa played by Chin Han and Aramaki played by “Beat” Takeshi Kitano. And the government security agency which the protagonists are part of, Section 9, is depicted as multi-ethnic in nature, drawing on the multi-ethnic societies which are a trope of cyberpunk, as seen in everything from William Gibson’s Neuromancer to Blade Runner or The Matrix trilogy. Seeing as Kitano’s Aramaki, the head of Section 9, speaks only in Japanese but apparently this is understood by all other characters, the implication may be that most characters understand Japanese.

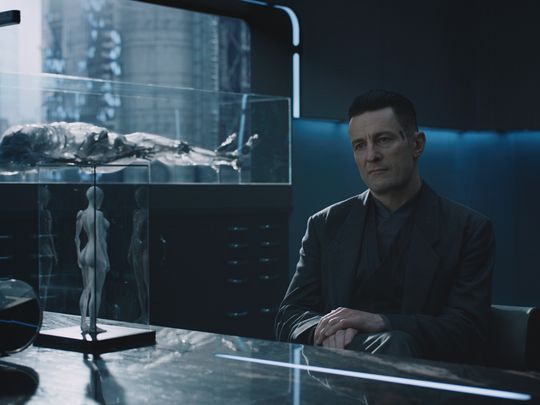

Depiction of a robotic geisha in the second Ghost in the Shell animated film (left) as compared to the live action adaptation (right). The live action depiction is notably more Orientalist

Depiction of a robotic geisha in the second Ghost in the Shell animated film (left) as compared to the live action adaptation (right). The live action depiction is notably more Orientalist

However, one strongly suspects that the casting of the film and the depiction of its setting as a multi-ethnic or vaguely post-racial was meant to allay criticism, seeing as the “whitewashing” controversy broke out early in the film’s production after the announcement of Johansson’s casting. Reports on earlier versions of the script suggest a more clearly American setting was considered. Either way, the genre of cyberpunk inflicts American anxiety about the rise of Asian economic powers in the 1980s and 1990s, as embodied in the fear that Asia would “take over the world”. This is a way in which the cyberpunk genre is not entirely unproblematic and oftentimes contains elements of Orientalism in its depictions of Asia, if it also contains a strong transnational aspiration at times.

But one can observe an egregious amount of Orientalism in the live action adaptation’s depiction of Ghost in the Shell’s setting. The two original Ghost in the Shell anime films, particularly the second film, engage in the exoticization of traditional Japanese tradition within aspects of the film’s setting. As part of the film’s broader thematics, this is for the sake of depicting a futuristic world which paradoxically continues to bear the strong traces of pre-modern tradition, rather than one in which technology has completely wiped away tradition as one might expect. Yet the live action adaptation seems only interested in mining Orientalist imagery for visual shock value. Unlike the original Ghost in the Shell films, there is no engagement with authentic aspects of traditional Japanese culture, such as the use of archaic Japanese in the soundtrack.

The Asian characters of the film are either minor in nature or their depiction is tainted by Orientalism. Chin Han’s Togusa in fact largely avoids the problem of Orientalism, seeing as the character speaks fluent English and is depicted as a regular member of Section 9, but he does not see much screen time. But we may note that Takeshi Kitano, who only speaks in Japanese throughout the film, is depicted in a clearly Orientalist manner. In iterations of the Ghost in the Shell franchise, one oftentimes observes intellectually sharp repartee in dialogue between the Major, Section 9’s field leader, and Aramaki. However, here, Aramaki comes off as a stiff and flat character and he primarily seems to be treated as an “Asian wise man” in his interactions with the Major, before abruptly unveiling yakuza-like fighting skills near the film’s conclusion in a manner referencing Kitano’s career as an actor and director. But instead of serving as a tribute to Kitano, the effect is Orientalist and quite kitschy, at that.

Takeshi Kitano as Aramaki. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Takeshi Kitano as Aramaki. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Nevertheless, the most jarring aspect of the film where racial issues are concerned comes from the climactic revelations of the film. The Major, in the live action adaptation “Major Mira Killian” rather than “Major Motoko Kusanagi,” was originally Asian before her original body was destroyed by Hanka Industries, then converted into a cyborg body and implanted with false memories. “Motoko” is posed as her original name, whereas her name after conversion to a cyborg is “Mira Killian.” “Motoko” is originally Japanese, but becomes white after being converted to a cyborg. The same is true of the film’s initial antagonist, Kuze, a victim of this same process also apparently once Asian.

This plot element seems to have been the film’s attempt to confront or justify the whitewashing controversy head on. And, honestly, though this is not at all what the Ghost in the Shell franchise is about, as some commentators have suggested, a film about racial transformation through cyborg body reconstruction could be an interesting film that engages with a number of contemporary issues.

Yet as a way to address the “whitewashing” controversy, this is completely tone deaf. What producers seemingly failed to realize was that this plot element would draw uncomfortable parallels, seeing as the charge that the live action Ghost in the Shell’s producers sought to kill the original film and whitewash it into a more easily palatable form by way of casting In this plot element, the film’s producers also draw easy parallels between themselves and the film’s villains, Hanka Industries.

Scarlett Johansson as the Major. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Scarlett Johansson as the Major. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

What did the producers think, that by giving the Major what is in some sense an “Asian-American” background in this way, this would be enough to allay criticism? Would Asian-Americans actually feel themselves represented on screen through this white character played by Scarlett Johansson? Or that by adding an element of self-incrimination, this would get them off the hook? As far as one can extrapolate, this seems to be what the film’s producers may have thought. Seeing as the scandal about whitewashing broke out early in the film’s production after the announcement of Scarlett Johansson’s casting as the Major, very likely, this plot element was introduced as a response to criticisms of whitewashing.

But that the film’s producers failed to grasp that the problematic aspects of this plot element would only make worse charges of whitewashing. This fact is evidence enough that Hollywood still has not truly understood the issue at hand. Frankly, one finds oneself rather beyond words at this completely tone-deaf and insensitive attempt to resolve the controversy.

Straying From Ghost in the Shell’s Cyberpunk Dystopia in the Setting

BY VIRTUE OF being a Hollywood film, any artistic ambiguity, open philosophical question, or complex plot element has to be reduced to the most simple of terms in the live action adaptation, which strays from its source material.

For example, part of the strength of the Ghost in the Shell franchise in worldbuilding is that it has always taken its cyberpunk setting as a given, in which most humans have cybernetic enhancements to their brains in order to connect to an omnipresent Internet and may have other bodily enhancements. Yet, few humans have full-body cybernetic augmentation on the scale of the Major, who is always depicted as a character who has a primarily human brain but an entirely mechanical body. The live action adaptation steers sharply away from this, in having the Major be the first human with an entirely mechanical body apart from a human brain, It suggests that the development of cyborg enhancements and an omnipresent Internet which can be neurally linked to humans is a recent development. Likely, Hollywood producers viewed this setting as requiring too much work on the part of the viewer to grasp easily because of its distance from contemporary reality and so sought to revert the overall parameters of Ghost in the Shell’s setting closer to present-day reality.

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Due to the franchise’s cyberpunk-inspired ethos, the setting of the different versions of the franchise have at times verged on the dystopian. if not outright dystopia, a degree of high moral ambiguity stemming from the film’s setting has always been present in the protagonists’ actions, who are always members of the clandestine government security agency known as “Section 9”.

Cyberpunk tropes oftentimes pose shadowy entanglements between the government and powerful corporations as a ubiquitous feature of near-future societies, suggested as the logical outcome of trends which one can observe in present-day society. This can be seen as a form of social critique deeply embedded within the genre. In Oshii’s original film adaptations of Ghost in the Shell, Section 9’s actions were always portrayed as part of corrupt, messy political maneuvering, although later television and OVA adaptations of Ghost in the Shell verge on portraying Section 9 as a group of incorruptible government agents who always act for what is right on the basis of unbreakable convictions as the live action adaptation does.

But going along with cyberpunk tropes, the live action film’s primary antagonist is the president of Hanka Industries, the powerful corporation which produced the Major’s cyborg body. But the film evidences an uncomfortableness with the sharpness of cyberpunk’s social critique of state-corporate ties. The film’s conflict is resolved in part through Section 9 head Aramaki interceding with the prime minister about Hanka’s actions, never mind that previously the film had suggested that part of why Hanka was allowed to break laws with impunity close ties with the corporatist state. So the state comes in at the end of the movie to resolve any and all remaining conflicts.

Peter Ferdinando as Cutter, the antagonist of the live action Ghost in the Shell. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Peter Ferdinando as Cutter, the antagonist of the live action Ghost in the Shell. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Indeed, this seems to contravene the spirit of the 1995 original. Perhaps unsurprisingly given Oshii’s coming-of-age in the wake of World War II and background in the leftist student movements of the 1960s, Mamoru Oshii’s work has the recurrent undertone of constant preoccupation with the possibility of unaccountable state actors, particularly in the fear of right-wing coups by the military or state security agencies.

The Dumbing Down Of Ghost in the Shell’s Intellectual Themes And A Betrayal Of The Spirit Of The Original

WITH THE dumbing down of the Ghost in the Shell franchise’s complex intellectual themes, however, the live action Ghost in the Shell outright betrays the original.

We can see this in that there is almost no ambiguity in the plot of the live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. The 1995 original has the Major raise the possibility that her brain might be one recycled in a new cybernetic body, with her memories of the past being false in nature. The live action adaptation takes this possibility and runs with this, making it the concrete backstory of the Major. An iconic scene drawn from the first film of a garbage truck driver implanted and manipulated through false memories is depicted as though this were a simple case of mind control, rather than the more sophisticated and threatening possibility of memory implantation and personality manipulation.

In the same vein, the death of Kuze at the conclusion of the second season of Stand Alone Complex is ambiguous in nature. With Kuze stating to the Major that “I’ll be going ahead.” It is ambiguous as to whether Kuze is speaking of life and death, or going ahead with his plan of uploading his mind into the Internet to achieve a form of immortality. On the other hand, the live action adaptation is quite clear about its version of Kuze uploading his mind to the Internet before the physical destruction of his brain. Likewise, in the original, the Major is depicted as willing to discard her physical body in the event of its destruction if it means some form of survival on the Internet. In some versions of the story, the Major does abandon her physical body for existence solely on the Internet. Whereas in the live action adaptation, the Major is depicted as apparently committed to her physical body at all costs, even if it means death.

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Indeed, to hammer a multidimensional plot into a linear and straightforward one, the live action adaptation sees the need to introduce characters completely absent from the original Ghost in the Shell such as Cutter, the president of Hanka Industries, and Doctor Ouelet, the doctor responsible for the creation Major’s cybernetic body. In no other adaptation is there as clear, direct antagonists as Cutter, apparently responsible for every one of Hanka Industries’ wrongdoings. Furthermore, in no other version of Ghost in the Shell does the Major have a single responsible “creator”, with other iterations of the franchise positing the Major’s cyborg body as the creation of various anonymous technicians, rather than any singular individual. Again, this returns to the film’s setting, in that the futuristic setting is taken as a given and its dystopian elements are highly anonymous and naturalized in nature. There is hardly the need to give evil some human face.

The film’s simplification extends to the film’s overall philosophical trajectory, which is where the live action adaptation betrays the spirit of the original work most of all. The film concludes with the Major reaffirming that despite her cyborg enhancements, the essential core of her being remains human. This essentialist humanism and moralism is something which the franchise has steered sharply away from. A large part of the franchise’s sophistication derives from its rejection of any banal essentialism about what constitutes the borders of the human, given the prominent theme of not only humans becoming part-machine, but machines seeking to become human present in all versions of the Ghost in the Shell franchise beyond the live action adaptation. We can see this in characters as the Puppet Master of the 1995 film or the Tachikomas of the Stand Alone Complex television series.

On the other hand, the live action film draws stark borders between machine and man in a manner belying anxiety about the implications of the themes which the original grappled with. With its lack of any non-human characters, the live action adaptation is marked by fundamental anxiety about technology in place of an exploration of technology’s limits and potentials in simultaneously perverting and expanding the boundaries of what it means to be human, and its final affirmation is of a banal essentialist humanity.

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

In regards to the dumbing down of these themes, one sometimes wonders if the film’s producers thought they were adapting RoboCop rather than Ghost in the Shell. A Hollywood adaptation necessarily entails simplification and condensation of the original source material and, in this, it cannot please everybody. However, with the live action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, it was not only a failure to engage with the original themes but a complete betrayal of its spirit. And so, rather predictably, the live action adaptation fails to capture any of its intellectual and philosophical complexity or its provocativeness.

A Simplification Of Ghost In The Shell’s Female Protagonist In A Heavily Sexualized Depiction

AS PART OF this simplification and reduction of Ghost in the Shell’s themes to banal, essentialist humanism, the Major is given the backstory of having had a family and having converted into a cyborg by Hanka after being kidnapped, whereas all past versions have always depicted the Major as an isolated individual with no family, as bound up with the overall alienation and anonymity present in the cyberpunk setting. In general, the heavily cyborgized members of Section 9 are depicted as having no family, while new recruit Togusa is usually depicted as the only member of Section 9 with a mostly unmodified body and a family. The Major’s depth of character from grappling with questions about the self which she cannot answer are totally erased from the live action adaptation.

As the Ghost in the Shell franchise is heavily oriented around the character development of its protagonist, the Major, her character is drastically simplified for the live action film. Indeed, the character of the Major in Oshii’sfilms is highly transgressive in nature, but this has to be sharply toned down for the live action adaptation in line with its essentialist humanism, particularly with regard to the Major as a female character. For one, the franchise is not unproblematic in regards to the fact that the Major is a heavily sexualized character in the original Masamune Shirow manga. As a result, this extends to the Oshii adaptation, as a characteristic of the original text which Oshii seemingly felt he had to include in order to be faithful to the original manga.

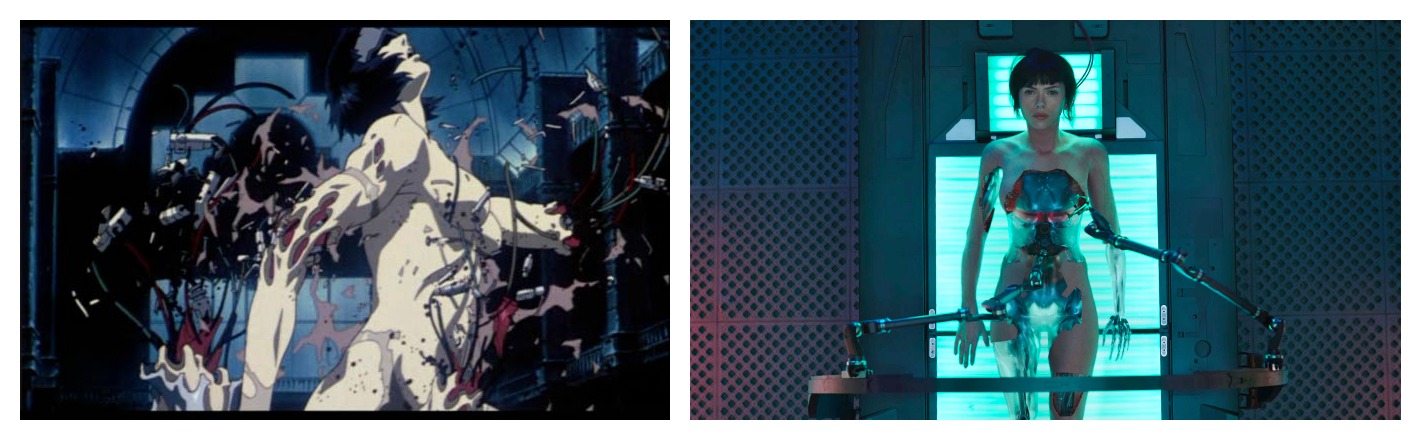

The destruction of the Major’s cyborg body in the 1995 animated Ghost in the Shell (left) versus a scene of the Major’s body being repaired in the live action adaptation (right)

The destruction of the Major’s cyborg body in the 1995 animated Ghost in the Shell (left) versus a scene of the Major’s body being repaired in the live action adaptation (right)

But we can observe the means by which Oshii subverts the sexualization of the Major in the original text during the famous climactic battle between the Major and a robotic tank at the end of the film, in which the Major strains her cybernetic muscles to the extent of mutilating her cyborg body in a highly grotesque manner, revealing the degree to which her female cyborg body is inhuman and radically rupturing apart the fetishistic depiction of female bodies in anime in an almost literal fashion. More generally, Oshii productions are by and large are devoid of the pornographic and misogynistic “fanservice” present in much anime, sometimes verging on strangely asexual depictions of sex. References abound in the 1995 Ghost in the Shell film and its sequel to feminist texts as Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto or early conceptions of the sexualized female cyborg as the 19th century text, Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s Tomorrow’s Eve, which indicate that Oshii is sharply aware of the problematic dimensions of the depiction of Ghost in the Shell’s female protagonist.

However, this never occurs during the live action Ghost in the Shell. Apart from scenes in which Scarlett Johansson’s body is focused upon in a highly sexualized manner, it is a crucial to note that during the climactic tank battle, there is no such destruction of the Major’s cybernetic body. The intactness of the Major’s body after the tank battle, in fact, seems meant to preserve the sex appeal of Johansson’s body, whereas Oshii’s aim seems to be to literally rupture and break apart the sexualization of female bodies in anime. The absence of this scene, an iconic moment of the 1995 film, is very telling about how the film presents the Major as female character always in a sexualized light, and greatly simplifies her character in line with a “Strong Female Protagonist” whose true purpose apart from any window dressing claims at being a strong character is in actuality to always be gazed upon voyeuristically by the audience.

Conclusion

IN CONCLUSION, we may note that live action adaptations of anime have been in the works since the height of anime’s popularity in America in the 1990s but Ghost in the Shell was the first major anime live action adaptation to see fruition after many years in development hell. It will also be a question whether we will see more adaptations in the future, whether such adaptations are similarly reductive of their source material, and what stance Hollywood will take regarding the casting of protagonists who may be Asian in the source material.

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell

One imagines that, rather than push Hollywood to address the racial issues within its films, the failure of Ghost in the Shell at the box office may actually lead Hollywood to back off from adapting non-American properties or movies based on source material in which the protagonist is not white. That remains to be seen. Certainly, corporate executives lashing out at calls for inclusivity and diversity in pop culture as a reason for poor sales in comics or films based on comics, would not be surprising, as we see in a recent scandal following comments by a Marvel Comics blaming poor sales on attempts to diversify the cast of historically white superhero comics. But, in the meantime, as it points to a larger problem in cultural depictions of race, the live action adaptation Ghost in the Shell is worth reflecting on for the negative precedent it sets for future live action adaptations of Asian franchises and future depictions of Asian characters.