by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

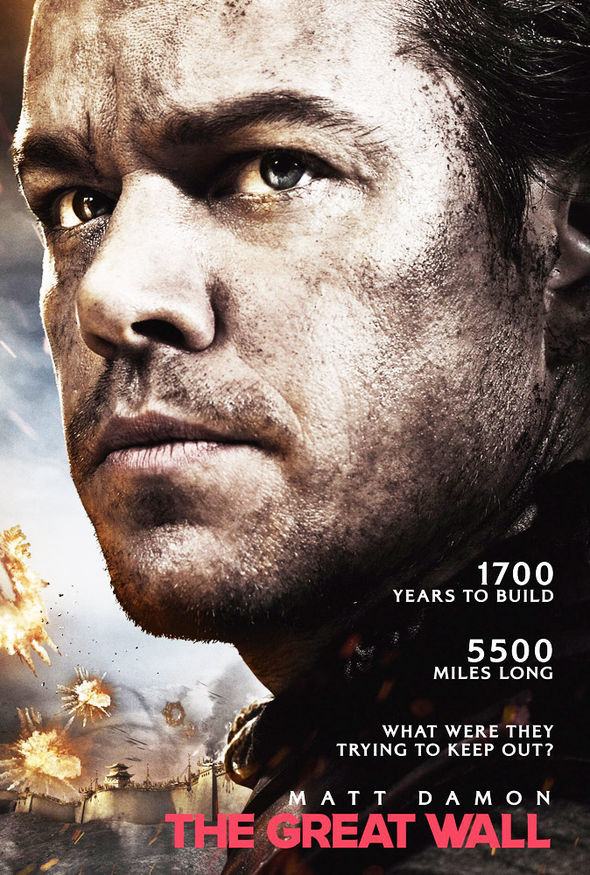

Photo Credit: The Great Wall

AFTER THE “whitewashing” controversy over The Great Wall starring Matt Damon, although it has not yet hit the American shores in which the majority of the backlash against the film was concentrated, the film is finally out. As such, we might critically reflect on the controversy now that the film has been released and can be judged on its own terms.

Namely, controversy previously broke out last year after the release of early trailers of the film, with some seeing the casting of Matt Damon in a role that seemed as if it should go to Asian actors a sign of Hollywood “whitewashing”—the casting of white actors in roles that logically should go to Asians or other people of color. Recent examples include Disney considering casting a white actor in the role of Mulan and the casting of Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi in the live-action adaption Ghost in the Shell, despite that the character should logically be Japanese seeing as the original is set in Japan.

As the film depicts China’s Great Wall as a bulwark against supernatural monsters, in the film’s trailers, Matt Damon seemed to play a character who was part of the Chinese military, which in the movie’s setting built the Great Wall as a rampart against these monsters. Obviously it seems like a logical inconsistency to have a white character play such an individual, who should be Chinese, particularly as Damon was the lead of the movie. And so, after a series of Tweets against the film by Fresh Off The Boat actress Constance Wu, a number of Asian-Americans reacted against the film, seeing it in line with Hollywood whitewashing.

What will Asian-Americans make of the film now that it is out? One wonders. Firstly, it is debatable whether this is a “whitewashed” film to begin with, The Great Wall’s trailer having rather inaccurately depicted the plot of the film. Secondly, the reactions of the Chinese government to the film strongly suggest that “whitewashing” in this film does not come from Hollywood, but from Chinese film executives themselves, a claim supported by reports in Chinese media.

White characters noticeably loom larger than Asian characters even in Chinese promotional materials for The Great Wall. Photo credit: The Great Wall

White characters noticeably loom larger than Asian characters even in Chinese promotional materials for The Great Wall. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Thirdly, on the basis of the film’s content, the racial dynamics of the film are demonstrably more complex than simply “whitewashing,” pointing to the fact that anything resembling “whitewashing” probably came from the Chinese film producers of the film. Asians “whitewashing” themselves is a more complex problem than “whitewashing” occurring at the hands of white, Hollywood film executives.

For example, what will Asian-Americans make of the fact that all white characters are depicted in the film as corrupt and individualistically selfish, given the foundations of western culture based on personal interest above all else, versus Chinese morality as founded upon devotion to the nation and the common interest—but that no Chinese characters have any subjective interiority and that it is only these western characters which have any semblance of interiority or character development at all within the film? These complex, underlying dynamics are what makes the film worth examining.

Why I Felt Compelled To Argue Against Other Asian-Americans About The Great Wall “Whitewashing” Controversy

FEELING COMPELLED to respond to what as I saw as my fellow Asian-Americans badly misunderstanding something at time of the “whitewashing” controversy, I argued contrarily to many Asian-Americans. My view was that many Asian-Americans had gotten it wrong. As the film was a Chinese-American co-production, I speculatively thought “whitewashing” in this film didn’t come from just evil white Hollywood executives, but quite likely from Chinese film executives, who featured Matt Damon as a white Hollywood actor in the film in order to give the film greater international appeal. I also saw the film as not an expression of Hollywood, but as an expression of the Chinese government’s attempt to strengthen Chinese soft power abroad. The Chinese state currently seeks to use film as a way to increase China’s ability to influence global politics by extending its cultural reach abroad, and Chinese film companies oftentimes have close ties with the state.

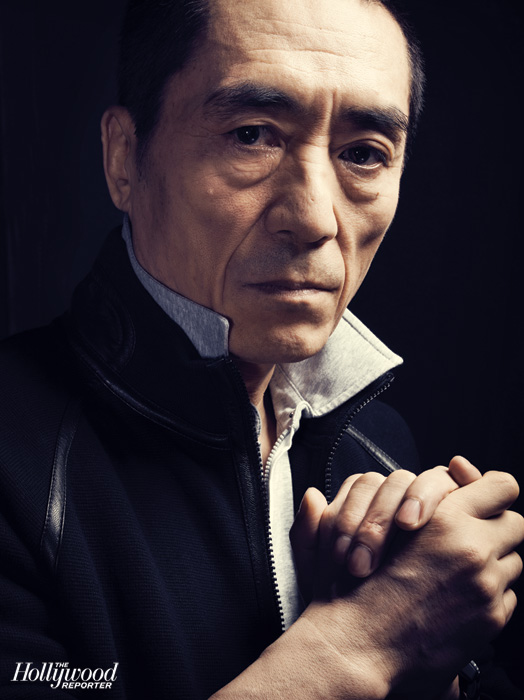

The Great Wall’s director Zhang Yimou, for example, has since 2008 been heavily embedded in Chinese cultural propaganda efforts. After becoming one of the most famous directors in the world as an art film director in past decades, Zhang’s film productions have become increasingly propagandistic. After directing the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a pivotal event in China’s efforts to demonstrate its ascendancy to the western world in the last decade, Zhang is oftentimes trotted out to direct the ceremonies of international events crucial for China’s international prestige, such as the ceremonies of international government summits.

Given the regulations that the Chinese government places upon all cultural production within its borders, it is unthinkable that a film on the scale of The Great Wall would not have some government involvement. The Great Wall is the most expensive film ever shot in China, with a budget of over $150 million USD.

2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremonies. Photo credit: Tim Hipps/FMWRC Public Affairs/CC

2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremonies. Photo credit: Tim Hipps/FMWRC Public Affairs/CC

And we would do well to keep in mind that even apart from financial motives, China’s wealthy sometimes feel it to be a mission to improve the status of their nation abroad. This is understandable, perhaps, for the wealthy of any nation, who may see themselves in a position to increase the standing of their home country.

But sometimes the Chinese state relies quite directly on its wealthy even in military efforts. We can see this, for example, in that China’s first aircraft carrier was actually first purchased by an independent businessman who decided that it was his patriotic mission to give China its first aircraft carrier and then “donated” the ship to China after he bought it. This vessel, the Liaoning, is the same vessel currently provoking international tension in the Taiwan Straits, sending panic throughout the Asia-Pacific.

Indeed, there certainly seem to be a nationalist dimension to the efforts of Alibaba’s Jack Ma to acquire one of Hollywood’s “Big Six” studios or to Dalian Wanda chairman Wang Jianlin’s drive to invest billions in all six of the “Big Six” studios. Wang is China’s richest man. Dalian Wanda owns Legendary, which though an America company, produced The Great Wall. Both Ma and Wang are individuals with close ties to the Chinese state. In general, one cannot expect major Chinese businessmen in the film industry or other industries not to have ties with the Chinese state, and apart from personal patriotic motives, benefitting the soft power aims of the state is one way to improve one’s relation with the state for future business enterprises.

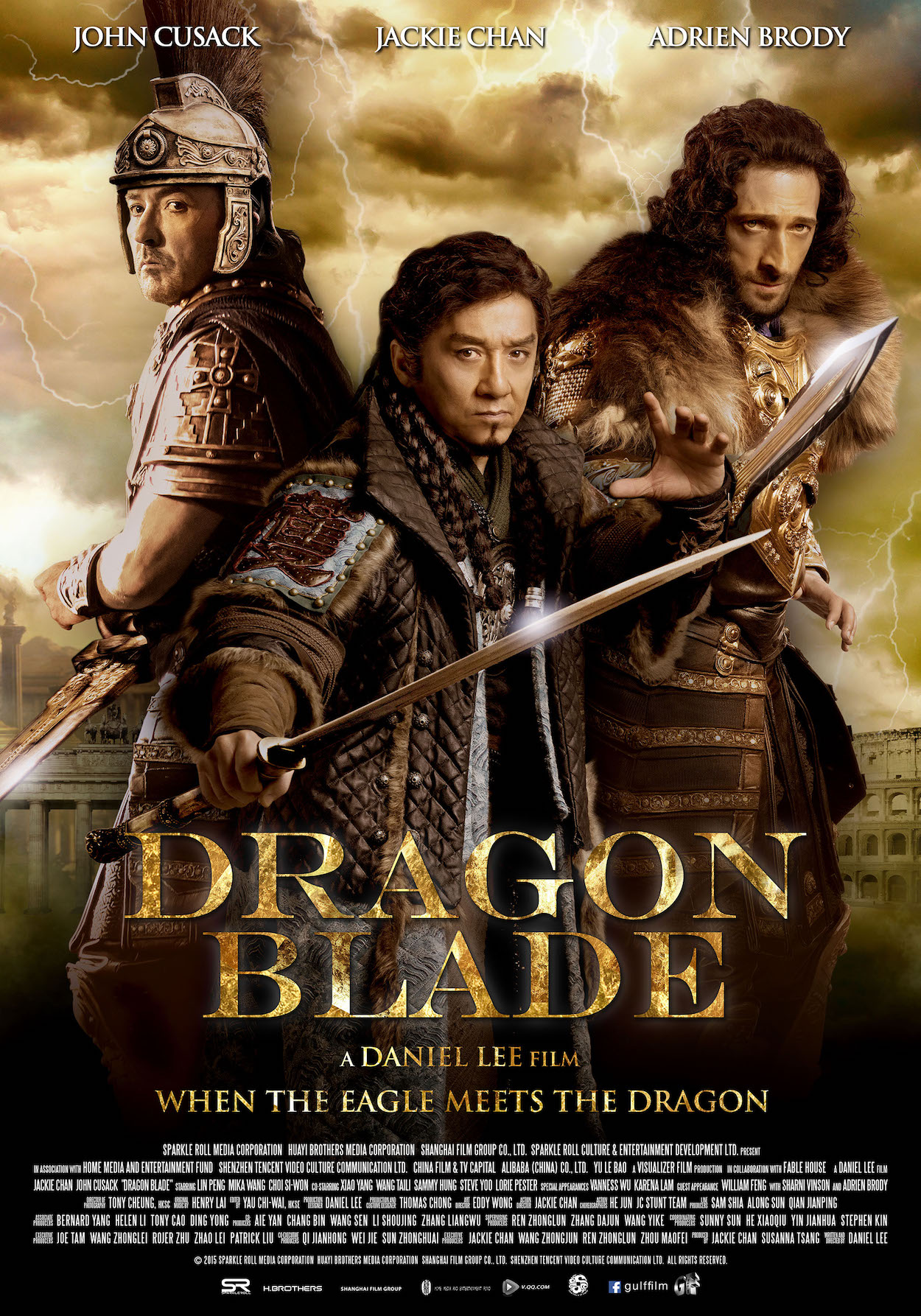

Thus, making Matt Damon the star of The Great Wall would not be so different from Hollywood’s attempts to break into the Chinese market by including Chinese actors in their films, oftentimes featuring actors famous in Asia but unknown in the West in incredibly minor roles, a phenomenon referred to as “flower vaseing” in contemporary Chinese slang. A recent movie which does this is recent Star Wars film Rogue One, which includes Donnie Yen and Wen Jiang in prominent roles, despite that the latter is almost entirely unknown in the West. Analogously, in recent years, we have seen a spate of films similar to The Great Wall, such as Dragon Blade and Outcast, which are similar in that they are all set in ancient China and thus spotlight Chinese antiquity in all its grandeur—but feature famous western actors in bizarrely central roles, in apparent effort to give the film international appeal. These constitute a sub-genre of contemporary Chinese film in themselves.

Film poster. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Film poster. Photo credit: The Great Wall

And it would also be a status symbol for a Chinese film to feature a well-known Hollywood actor such as Matt Damon. With the political and economic rise of China, racial dynamics in China often are such that association with white people are a sign of status for many Chinese—that is, a sign of global cosmopolitanism as tied to economic power. For example, in China there exist services to “rent out” white people to attend events as a status symbol.

As such, I saw The Great Wall as reflective of racial dynamics within China, not America, and the sociopolitical peculiarities of China as a nation. Therefore, The Great Wall could not be blithely seen as an example of Hollywood whitewashing, but had to be treated as a more complex phenomenon. As the film was not out at the time, I could not make any final judgements, but my knowledge of contemporary Chinese film production and my sense of racial dynamics in China suggested that this was not simply a case of Hollywood whitewashing.

Backlash I Received From Other Asian-Americans

PERHAPS UNSURPRISINGLY, many Asian-Americans took offense to my claims. I did not deny that “whitewashing” exists, nor that it is a problem, just that The Great Wall was not necessarily an example of it. Some bristled at my suggestion that “whitewashing” could come from anyone other than Hollywood executives. Particularly, some did not like my suggestion that Asian-Americans were projecting American racial dynamics onto Asia or, in this case, China.

My view is generally that Asian-Americans sometimes actually attempt to return many of the world’s racial problems back to America, because the majority of their life experience is in America and not Asia. And so Asian-Americans can sometimes be quite America-centric in how they look at racial problems in Asia or across the world. For example, if whitewashing is purely a problem which originates from evil white Hollywood executives, that returns the problem to being purely an American problem—something within their cultural standards of reference as individuals who have spent most if not all of their lives in America. Ironically, the claim that whitewashing was purely a problem from Hollywood also robs Asians of any sense of agency—only white people can be the movers of the world in any way, apparently.

Yet as my claims troubled the senses of identity of some Asian-Americans, they provoked backlash against me. Some accused me of being a self-hating Asian-American. Or, seeing as I do not have an recognizably “Asian” first or last name, they assumed that I was a white person trying to tell Asians what to do.

Zhang Yimou. Photo credit: Hollywood Reporter

Zhang Yimou. Photo credit: Hollywood Reporter

Likewise, I commented that Asian-Americans do not necessarily understand Asia and its social dynamics simply by virtue of Asian descent without having lived there and without speaking and reading the language fluently. I was therefore accused of seeing myself as better than other Asian-Americans, for thinking that I knew more than they. Nevertheless, more than one of my Asian-American interlocutors in fact did not actually know who Zhang Yimou was, thinking he was only some no-name Chinese hack hired by Hollywood to put a Chinese name on the film—despite the fact that he is perhaps the most famous Chinese filmmaker alive today. Frankly, I can only find that incredibly disappointing about my fellow Asian-Americans.

Attempts By Chinese State Media To Defend The Film Indicative Of The Film’s Importance To China

WHILE MY CLAIMS about The Great Wall’s film production were actually speculative at the time, after watching the film and noting responses to the film within China by the Chinese government after it was released, I generally view myself as vindicated in my claims. Notably, the Chinese government has seen fit to jump onto the Asian-American bandwagon of railing against “whitewashing” in the past, as expressed in state-run media publications as the Global Times or People’s Daily.

The Chinese party-state perceives American cultural hegemony as dominant in the world and it seeks to chip away at that to try and attain a similar position of global influence. Claims by the Chinese government that America contains hidden racism, as seen in Hollywood “whitewashing”, is a certainly one way to undermine the legitimacy of the claimed universality of American cultural productions. And so, the Chinese government is fond of attempting to co-opt Asian-American criticisms of the American culture industry for “whitewashing”. This also serve to mask the widespread, systematic ethnic discrimination that Chinese government perpetuates within its borders by relativizing Chinese standards and American standards.

But the People’s Daily took the opposite tack with The Great Wall. Actually, seeing as the film was poorly received within Chinese borders, the People’s Daily lashed out heavy-handedly at Chinese moviegoers and film review websites for giving The Great Wall low ratings. Why? Because such reviews were damaging the Chinese domestic film industry and, in this way, failed to be sufficiently patriotic. As The Great Wall is the most expensive production in Chinese film history, you can bet the Chinese party-state has a lot bet on it in efforts to make Chinese film better known internationally, again, as a form of soft power.

Film still. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

Film still. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

I originally saw links between Legendary Films and Chinese production companies as a sign that the film production may have still been primarily Chinese in nature, with Legendary possibly brought on in order to give the film American window dressing for much the same reasons Matt Damon was brought on as the film’s lead actor. This seemed to be backed up, again, by attempts by Chinese businessmen with strong ties to the Chinese state such as Jack Ma or Wang Jianlin to acquire Hollywood studios, in particular by the fact that Wang was Legendary’s owner. But so much for insistent claims by Asian-Americans that, while The Great Wall was a coproduction between America and China, that this was still an American film—and not a Chinese one in any way.

Was The Great Wall A Whitewashed Film At All? Were Asian-Americans Too Quick To Judge?

YET NOW THAT the film is now out, we might examine the contents of the film, too. To begin with, was the film “whitewashed” from the outset in its casting of Matt Damon? Actually, that is a good question.

Matt Damon is not cast in the film as a white man playing a role which should go to a Chinese actor. Damon’s role in The Great Wall as a European mercenary who comes to China in what was the European Middle Ages could not be played by a Chinese actor any more than he could play the role of a Chinese mercenary coming to Europe during the same time period.

Perhaps Asian-Americans or others would do well not to jump to conclusions about films before they come out, on the basis of their trailers alone. Or, seeing as the people who produce film trailers are usually not the same people who produce the films themselves, perhaps the people who produce film trailers should just produce more accurate trailers. This fact has already been the doom of more than one action film in the past year.

Matt Damon’s character of “William” in the film. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Matt Damon’s character of “William” in the film. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Would this casting have provoked such outrage from Asian-Americans if not for misperceptions that occurred because of the film’s misleading trailers? One wonders. Again, what we see in The Great Wall is more reminiscent of Hollywood “flower vaseing”, except that western actors have been featured in central roles by individuals who are Chinese film executives—and Chinese film executives themselves sideline Chinese actors in favor of these western actors for what are films that have a propaganda aim for China. Either way, what would be present in The Great Wall is not the simple phenomenon of Hollywood “whitewashing” at the hands of white people but the more complex phenomenon of Chinese “whitewashing” themselves in order to give the The Great Wall international appeal.

And so, we should examine the racial dynamics of the film itself. These are telling about how the film, in fact, represents an odd overlapping of Chinese and Hollywood film production, seeing as the film was in fact a American-Chinese co-production. But the film’s ultimate trajectory seems to have been determined by the Chinese film executives involved in its production.

A Poorly Made Film In All Aspects, Much Less A Zhang Yimou Film

DAMON PLAYS “William,” a European mercenary who travels to China, Conquistador-like, driven by myths of gunpowder during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). William is the film’s protagonist. After encountering Chinese troops fighting off monsters—the true purpose of the Great Wall of China in the film’s story is to keep supernatural monsters out of China—William’s internal struggle is between whether to stay and help his newfound Chinese allies, prompted by romantic interest in Jing Tian’s General Lin of the Great Wall garrison, or steal the gunpowder and flee for his personal interest. This provides the majority of the film’s dramatic momentum.

The insertion of western characters, usually mercenaries, soldiers, or outlaws in pursuit of rumored treasure or fleeing from Europe, is common to the sub-genre of contemporary Chinese film to which The Great Wall belongs. As can also be seen in Dragon Blade and Outcast, this serves as a way to bring European antiquity in contact with Chinese antiquity, with the view that this is representative of a civilizational meeting between “Western civilization” and “Eastern civilization”. But in this sub-genre, the setting must be within China. Due to the nationalist underpinnings of such films, it is a specific point that Chinese landscape must be showcased in a way to impress western viewers with the grandeur of ancient China’s aesthetic splendor. As such, plot-wise, western characters must be brought into China rather than Chinese characters brought into a western setting.

But if one normally expects visual splendor from a Zhang Yimou film, this is poorly done. The film’s visual effects and design choices fail to truly impress. The “tao tie” monsters which attack the Great Wall and the tawdry green blood they bleed particularly jump out as poor visual effects.

Shanshui-like scenery in the film. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Shanshui-like scenery in the film. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Some uses of the Great Wall as a siege weapon are innovative. And as with the attempt to feature Chinese “landscape”, attempts in the film are made to feature scenery reminiscent of Chinese artwork, such as shanshui paintings, a sky filled with kongming lanterns, and China’s vast deserts.

Yet these simply come off as CGI, rather than genuinely beautiful landscape, in the way of, say, another recent Sinophone film as Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s The Assassin and its meticulous, masterful use of actual Chinese landscape. The Assassin, which some critics have deemed to be one of the most beautiful films ever made, was notably shot on a $14 million USD budget as compared to The Great Wall’s $150 million USD budget.

The effects in The Great Wall are all too artificial in nature. Few will think that this is a true representation of Chinese landscape. With the sheer amount of poor, wastefully expensive CGI, one is vaguely reminded of a Michael Bay film, except instead of explosions (though one has plenty of those as well), one has attempts at depicting Chinese landscapes. One is struck by the degree to which the film is evocative of a “nouveau riche” mentality that pumping money into the budget for visual effects and CGI automatically means creating beautiful and visually attractive imagery.

An example of female costumes in the film. Film still. Photo credit: The Great Wall

An example of female costumes in the film. Film still. Photo credit: The Great Wall

And where The Assassin and past Zhang films such as Hero ($31 million USD budget), House of Flying Daggers ($12 million USD budget) and Curse Of The Golden Flower ($45 million USD budget) had beautifully designed, ornate costumes as representative of aestheticized Chinese antiquity, the costumes of the Great Wall garrison troops do not impress. One is vaguely reminded of playing real-time strategy games with different troop units in the 1990s, really, with the different troops stationed along the Great Wall receiving a different color: Silver for the commands, black for the foot soldiers, red for the archers—and blue for the female spear-wielding dragoons that acrobatically dive from the Great Wall to fight the monsters as they scale the wall, wearing skintight “armor” intended to show off their figures as they gyrate through the air acrobatically. Though thankfully we avoid anything on the level of skimpy ‘80s “bikini armor,” some shots directly focus on their breasts. All of the female characters in the film belong to this class of female dragoons, including General Lin, who begins as one of these dragoons before being promoted to general of the Great Wall garrison.

Hilariously enough, plot-wise, the presence of female spear-wielding dragoon is justified as suggesting Song dynasty China was a more gender-egalitarian society than the West, despite the fact that foot binding became popular in the Song. And we may note if past Zhang films have featured “mass ornament”-like human displays as a sign of China’s military might, this was always presented with a degree of moral ambiguity. Here, however, we see Zhang simply glorifying the Chinese military “mass ornament”, without any hint of authoritarian undertones to this. In line with the film’s militaristic underpinnings, almost any character which is not a soldier is depicted in a negative light, as in the depiction of corrupt and effete Song dynasty court officials.

With some of the costumes, one is vaguely reminded of 1990s anime Ronin Warriors. Photo credit: The Great Wall

With some of the costumes, one is vaguely reminded of 1990s anime Ronin Warriors. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Regardless, with past Zhang films, whether with the details of the background or costumes, it was generally masterful subtlety which lured in viewers into an aestheticized vision of Chinese antiquity. But, despite the large budget, the film’s attempt to hammer visual splendor into the viewer comes across as cheap and inauthentic. Some shots of the film in fact just come off as poor cinematography, as seen in an early scene in which one of the monsters is knocked off of a cliff which previously had not been introduced as a visual element in the shot. And so, it seems that we can neither expect a coherent plot, consistent filmmaking technique, or even at least visual aesthetic splendor from Zhang Yimou as a directot anymore.

And the film’s conclusion, with the killing of the “queen” of the monsters by William and Lin working together seems rushed, without any proper sense of dramatic tension leading up to it. Seeing as the conclusion has an abrupt shift in setting from the Great Wall to the imperial capital of the Song, Bianliang, this second setting of Bianliang seems underdeveloped as compared to the Great Wall. Probably another large-scale battle scene, set in the urban spaces of Bianliang instead of set on the ramparts of the Great Wall, would have made for a more proper sense of pacing and development for the film’s final act, as compared to the relatively brief scenes of Bianliang troops fighting off the monsters unsuccessfully and the protagonists fighting their way through the city before William and Lin are successful in killing the queen. But maybe they already spent too much on CGI and ran out of budget?

Juxtapositions Between East and West Within the Film

WE WOULD DO well to note that three western characters which appear in The Great Wall are all individuals who have ventured into China in search of black powder. It is suggested through exchanges between William and Lin that the two differ because of the differences between their respective cultures.

William is motivated by self-interest and greed, in the belief that finding gunpowder and bringing it to Europe will make him rich. William is a mercenary, loyal to no country, having fought for many countries. He is even willing to turn on allies without hesitation if they become a burden, since all friendships are for him conditional on how they benefit him, embracing a “survival of the fittest” mentality. It is suggested that this is a feature common to all westerners, because of their culture. Westerners are, in fact, quite directly compared to the “tao tie” supernatural monsters that besiege the Great Wall, which are said in the film to be a punishment sent down from the heavens to punish human greed.

Jing Tian’s character of General Lin. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Jing Tian’s character of General Lin. Photo credit: The Great Wall

On the other hand, Lin is motivated by patriotism and ties of kinship with her fellow soldiers and countrymen. Lin values “xinren” (信任), or trust in her fellow countrymen, and as a soldier in defense of China, she is willing to sacrifice herself for the greater good without hesitation. As the film takes pains to drive home, this makes her heroic.

William’s eventual coming over to the Chinese side and being willing to take risks for the sake of the greater good is his primary mode of character development in the film. On the other hand, Lin and other Chinese characters have no character development at all. All of them remain as static characters with self-sacrificing ideals to be strived towards, but which have no interiority, development, or personal flaws themselves.

Of the sub-genre of contemporary Chinese film it belongs to, The Great Wall is unique in that the central plot relationship between western and Chinese protagonists is romantic in nature. On the other hand, the film Dragon Blade merely centers on a homosocial male friendship between Jackie Chan’s Huo An and John Cusack’s Lucius, a Chinese and Roman general, respectively.

Obviously, by the time the film concludes, William has fully come over to Lin’s side and this represents the completion of his character development. Films in which the central Romantic tension between male and female protagonists from different cultures in which the male protagonist ultimately comes over to the cultural viewpoint of the female protagonist are nothing new (and such films can only be about the male protagonist coming over to the viewpoint of the female protagonist). In fact, due to this plot structure, The Great Wall shares much resemblance with the Dancing With Wolves, Pocahontas, or Avatar type of narrative where a westerner learns to shed his western, material trappings after coming in contact with Native Americans or blue alien Na’vi.

Yet we might say such films are, of course, produced out of white guilt, more than anything else. With The Great Wall, the aspect of the film which is Chinese propaganda is to demonstrate the superiority of Chinese culture over western culture. These are the contradictions of the type of film The Great Wall belongs to, seeing as they feature western actors in central roles, and sometimes sideline and “flower vase” Chinese actors in what are actually Chinese films.

Film still. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Film still. Photo credit: The Great Wall

But we may importantly note the strong element of mutual cultural stereotyping present here. William represents a Chinese stereotype of materialistic, individualistic western culture. On the other hand, Lin represents a stereotype westerners often have about Chinese, but that Chinese also often have about themselves—which is that, in contrast to the West, Chinese are group-oriented, self-sacrificing, and found their society not based on individual interest but on the collective interest.

Again, this probably returns to the nature of the film as a American-Chinese co-production (for example, in that the script was written by Hollywood script writers but the director was Zhang Yimou), in which the cultural stereotypes of westerners about Chinese and about themselves (perhaps with an element of white guilt in the latter) are merged into the cultural stereotypes of Chinese about westerners and about themselves. This is probably the most fascinating thing about the film. However, as it is a strong intent of the film to display the aesthetic grandeurs of ancient China to an international (read: western) audience, there is a large degree of apparent Orientalism present in the film’s depiction of its Chinese characters as moral exemplars, as most visible in the scene in which Lin explains the values of “xinren” (trust) which all Chinese apparently abide by. But Orientalism and self-Orientalism are not so easy to parse out in a film such as The Great Wall.

Ultimately an Expression of the Concerns of Empire?

YET THE FILM’S ultimate conclusion is that after the protagonists successfully kill the “queen” of the supernatural monsters besieging China, William returns to Europe, leaving Lin behind. Why the unfulfilled romantic conclusion? Perhaps between East and West, never the twain shall meet, if they can come to some degree of mutual understanding?

The conclusion of Dragon Blade is that John Cusack’s Lucius dies, bequeathing Jackie Chan’s Huo An with his status as a Roman centurion and his mission to defeat the evil Tiberius, wiith the integration of Lucius’ surviving Roman troops into the ethnically diverse Chinese peacekeeping force that Huo An leads. The suggestion seems to vaguely be that western power internationally has declined, and so the West (as represented by Rome) should cede its international peacekeeping role to China now. As all the Roman characters are played by Americans and American national iconography sometimes harkens back to Rome, this would seem to be a reference to America’s current role as the “world’s policeman” and the suggestion that America should step back and let China take up such a role. As a bizarre epilogue that is part of the story’s historical frame narrative, the site of the battle between Huo An and Tiberius is later discovered by cosmopolitan Chinese-American archaeologists, as representing the unification of Chinese and western culture or, perhaps more to the point, the integration of China into a vision of the global, cosmopolitan culture currently dominated by the “West”.

Film poster for Dragon Blade. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

Film poster for Dragon Blade. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

The Great Wall also shares with Dragon Blade a historical frame narrative through the story’s claim to be one of the numerous “legends” about the Great Wall in its opening title card. But William states that his purpose in leaving is to return his friend Tovar to Europe. We can see that there is no way for him to be together with Lin, because that would be for him to “possess” her in a way. Rather, he is to keep to his own people, and enforce the proper national boundaries, it seems, in making sure that greedy Europeans as he once was do not venture to China in the hopes of plundering its riches. Indeed, interracial relationships between Chinese and westerners have certainly been something which the Chinese government has warned against in recent times, with the claim that foreigners could be spies.

Yet it seems that even with foreigners who have become “enlightened” through their encounter with Chinese civilization like William, interracial relations are still best kept away from? And that, at best, what such “enlightened” westerners should do is go back home to police the borders between the West and China? That, as China often claims in its international diplomacy, we have our own way and that you should just leave us to do it? This would be China’s so-called policy of “non-interference” in the affairs of other nation-states, never mind that this coexists with claims that China should be allowed to step into the role of the world’s superpower currently occupied by America, as we see in Dragon Blade.

Films as Dragon Blade, Outcast, and The Great Wall are ultimately expressive of different, sometimes conflicting facets of contemporary China’s imperial ambitions. And so, if the film most certainly contains mixed elements of Hollywood and Chinese film production, the ultimate trajectory of the film seems to be drawn from contemporary Chinese nationalism.

Ultimately an Expression of the Anxieties of Empire?

IF THE AIM of The Great Wall was for China to produce a film on par with Hollywood, as the most expensive film production in Chinese film history, it is to be questioned whether China has met its aims. Certainly, the film is one which is incoherent plotwise, badly written, and badly structured, yet no less so than many a Hollywood film. China can now claim it has the ability to produce a film no less incoherent than any Hollywood film. One does, in fact, see a marked improvement in quality from previous efforts as Outcast and Dragon Blade.

Film poster. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Film poster. Photo credit: The Great Wall

But given the film’s enormous budget but its poor performance in China, one is reminded of Adorno’s observation that with all the resources that the culture industry can muster, sometimes it still misfires and does not always succeed in creating hits. Yet so, too, are many Hollywood films incoherent and they do quite well in American box offices.

It is really to be questioned whether the film will meet with success in America and elsewhere. Although the film was poorly received by audiences in China, sometimes films which do poorly in America unexpectedly do quite well in China—and vice-versa. Americans may react badly to the films anti-western undertones. Or perhaps the controversy over “whitewashing” will actually serve as good advertising for the film down the line. And, apart from the question of how the film performs, we shall see as to what reactions are from Americans, Asian-Americans, or other international audiences, “western” or “Asian”.