Reflections by an American Participant in the Executive Yuan Occupation

by Bolao

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: 王顥中

Bolao (伯勞) is the pseudonym of an American of Taiwanese descent living in Taipei. Through a strange set of circumstances, though an American by birth and upbringing, he was involved in the attempt invade and occupy the Executive Yuan, Taiwan’s executive branch of government. The following is his investigation into and personal account of the Executive Yuan and Legislative Yuan occupation, both of which he was a participant in.

The Legislative Yuan

WITH THIS ESSAY, I want to focus on with the Executive Yuan occupation. Within the annals of Taiwanese history, the Legislative Yuan occupation will be remembered for eternity. The Executive Yuan occupation, I’m not so sure—because immediately thereafter, efforts were made to bury it, even from those who had participated in it. As for me, I intend to perform an excavation to bear witness to this truth to the world. Yet the Legislative Yuan was the beginning. So it’s a natural starting point.

Executive Yuan, March 23rd. Film: T.Y.

The night of March 18nd, 2014, I participated in the attempted Legislative Yuan occupation because I had spent the previous five months intersecting student groups involved in social movements of various sorts, particularly around the anti-nuclear movement. I had been since high school on the Left and, moreover, an activist. It was something like automatic instinct for me to seek out social movements and attempt to embed myself within them. Truth be told, though I was from Taiwan in some sense, Taiwan wasn’t even the first East Asian country I had done this with.

I turned up around half past midnight that night. It was exciting, certainly, to be a part of that history. The strangely farcical series of events which led to me participating in the attempts to occupy not one, but two branches of government of a country I wasn’t even from began with a college student group I had been hanging around with for several months.

I had begun intersecting this group when I encountered a rather English-competent student activist at a weekly anti-nuclear protest during a point at which my own Mandarin conversational, if not listening, ability was rather woe begotten, then started slowly inching in upon her and activist friends in my attempt to push my way into getting to know Taipei social activism. So I ended up forcing my way into her group of friends as the strange, pseudo-foreigner that was attached to them. It was like that for awhile during the period in which the anti-nuclear movement was the big thing in Taipei social activism.

The Legislative Yuan occupation I was present for because I had heard about it through Facebook. The girl I had met was one of the first occupiers within the Legislative Yuan and, actually, she ended up being one of the activists who stayed through the entirety of the occupation. When the occupation went down and I found out through the Facebook posts of people I knew what was going on, I recall debating to myself whether the occupation would last through morning. After hearing that she was in the Legislative Yuan, I was worried, and I noticed more and more of our friends were arriving on site. I decided to jump into a taxi and head to the Legislative Yuan.

I stayed until morning. As the crowd began to force its way into the courtyard of Legislative Yuan, I was always hanging out around near the back of the crowd as it became more and more brazen as the night went on. I was a foreigner, after all. I needed to keep open a escape route. If I was arrested, that would be the last I would ever see of Taiwan. Hell. I didn’t know what exactly would happen to me if I—an American, would be arrested in this strange set of circumstances. I imagine it’d play out like that American who tried to meet Aung San Suu Kyi when she was under house arrest so many years ago, swimming across a lake to make it to her home and claiming that it was a mission given to him by God when apprehended by Burmese police.

Night of the Legislative Yuan occupation. Photo credit: Bolao

Night of the Legislative Yuan occupation. Photo credit: Bolao

Well, nothing happened to me that night. I eventually left around morning, because between all the attempts to force the police out of the Legislative Yuan building as a whole so that the occupiers could control the entirety of the building rather than just the legislative chamber, none seemed to be successful.

I guess I was right to leave then, since for the entirety of the occupation, there was no point at which the occupiers ever controlled the entirety of the Legislative Yuan building. Too afraid of arrest, I never went into the Legislative Yuan, much to my regret in the present.

That was the first time I came away with a grasp of the dimensions of Taiwanese civil society. Encountering, chatting with, and then sitting across from one of my student activist friends from the group I had been hanging out with on Jinan Road around when I arrived, I found that one of my NYC-based Japanese activist friends had shared a post regarding the Legislative Yuan occupation that had been translated into some dozens of languages. When I looked to see who she had shared it from, I saw that the person who she had shared it from knew the person I was sitting across from.

I posted on her Facebook wall, “I’m here in front of this thing right now, believe it or not. How does your friend know mine? Small world.” I was, of course, surprised when she responded and informed me that it was a viral post, which had had close to 9,500 likes, 15,000 something shares, and had been translated into over thirty languages—and here I was sitting across from the person who had written the post. What had I stumbled into? I recall asking myself that at the time.

I learned later that Taiwan had the highest Facebook penetration of anywhere in the world. 60% of the population on Facebook. Perhaps uniquely of anywhere in the world, these kinds of phenomena were, in fact, far from strange in Taiwan. For all the skepticism I had harbored over the years towards those who made so much of social media in social movements, well, here was facing a case in point.

Maybe an hour later, I later found myself that night surveying the courtyard of the Legislative Yuan, climbing onto the wall surrounding it, while this same friend stood on top of a news van with a megaphone, issuing directions to those who were trying to force down the front gate. And since the first of my activist friends in Taiwan had been inside to begin with along with another one of our mutual friends—and I knew this from Facebook—I was struck by what an impressive cast of people, almost all younger than me, that I had stumbled upon.

I recall a sense of thrill mixed with fear for much of that night. I was recorded directly on security camera while standing on the gate of the Legislative Yuan. While climbing on top of the courtyard wall outside of the Legislative Yuan in order to get a better view of within, I noticed a security camera directly facing me, with a protest banner somebody had hung underneath it.

I raised up the protest banner to cover up the camera, but for months afterwards, I agonized over whether my face had been recorded on camera and whether, with the fears then that the Taiwanese government was using facial recognition software to nab protestors, that I would be arrested and deported on the basis of my image being recorded on camera in that moment.

Though my connections with Taiwanese activists, particularly student activists, had already been strong before, it was probably after that night that I became “one of them”. They had seen that I was willing to take the same risks they were, after all. And well, without getting too much into it for risk of revealing who I am, it’s probably not incorrect the entire course of my life shifted from then on out. I had been involved in social movements and activism for a long time, but my fights were different from then on out.

Courtyard of the Legislative Yuan during the night of the initial occupation. Photo credit: Bolao

Courtyard of the Legislative Yuan during the night of the initial occupation. Photo credit: Bolao

I had other misadventures, variously worth reporting on or not worth reporting on. I encountered my friend inside the Legislative Yuan only once during the occupation, when I ran into her in front of the entrance to the Legislative Yuan.

Without going into details, I regret a great deal the ensuing series of events which came to my knowing little detail about the inside of the Legislative Yuan or even learning about my friend’s experiences, though I have only myself to blame for that in more than one respect, but I’m fairly confident that with the amount of photographers, writers, and filmmakers inside the Legislative Yuan, the Legislative Yuan occupation is well documented enough for Taiwanese history. Maybe not for Anglophone accounts of Taiwanese history, which are generally quite poor to begins with.

Whereas English media is concerned, there were those who reported on the Legislative Yuan, but even then certain details were left out. For one, that supposed Black Island Youth Liberation Front spokesmen Lin Fei-fan and Chen Wei-ting weren’t even members of the actual Black Island Youth Liberation Front members to begin with, but were student activists of some notoriety from the anti-media monopoly movement. The leader of the Black Island Youth Liberation Front was and always had been Wei Yang and the organization had been formed implicitly for the purposes of opposing the CSSTA trade bill. It was only after the media latched onto the notion of the Black Island Youth Liberation Front being the group in control of the occupation that Lin Fei-fan, Chen Wei-ting, and others became part of the “extended” Black Island Youth Liberation Front.

Likewise, while pro-KMT news sources reported on the occupation being a mess on the inside, and pro-Taiwan media insisted upon the internal discipline of the students in maintaining the cleanliness of the legislative chambers, to my understanding, the first floor of the Legislative Yuan was a mess for some time until the Black Island Youth Liberation Front came in and enforced order.

Again, this is the truth, and I think it bears telling, not hiding. Who really cares about the chamber of the Legislative Yuan getting messed up when the fate of Taiwan is at stake?「小 case」, as they say here. Even I don’t think certain details need revealing in the present, for example, that which might lead to arrest of student activists. But I am devoted to letting the truth speak for itself. It’s the only way things will change in a society as socially repressed as Taiwan often strikes me as being.

Subsequently, let’s turn to the Executive Yuan occupation. I think that’s what’s really interesting here about this account of mine. Because there were plenty who were present, could, and did comment upon the Legislative Yuan occupation. But as the perhaps one foreigner who attempted to storm the Executive Yuan, these are experiences unique to me. It’d be a waste letting them remain only in my memory.

The Executive Yuan

THE EVENTS THAT transpired five days after the occupation of the Legislative and led me on the night of March 23nd charging the police barrier outside the back door of the Executive Yuan with a number of Taiwanese students are probably even more ridiculous where I, this strange interloper from abroad, was concerned.

Maybe I’m just an idiot with an inability to distinguish between the shapes of buildings, but in light of the similarity in structure between the Legislative Yuan and Executive Yuan, my lack of knowledge of the geography of the area around Shandao Temple at the time, or that I just wasn’t paying attention, I wasn’t totally clear what branch of government I was charging the gate of during that period in time. I actually was not totally sure if it was the back gate of the Legislative Yuan we were charging, in an effort to clear the building for occupiers. But I knew it would be dangerous. I knew that I might come out of it seriously injured, or worse. Yet even then, as we were preparing to charge the Executive Yuan, I would be one of the only human beings in history who had gone through what I had gone through—or at least, certainly, the only American to do so.

The courtyard of the Executive Yuan on March 23rd. Photo credit: 李忠憲

The courtyard of the Executive Yuan on March 23rd. Photo credit: 李忠憲

And so I found myself charging down the executive branch of government of a country I wasn’t even from. Had this been America, certainly, charging down the White House would have gotten me shot to death. Without being too hyperbolic, in a revolution, there certainly are times in which you have to decide when you have to decide whether its worth sacrificing your life at that moment in time within the the span of a few seconds. Maybe the problem with the Sunflower Movement is that it did not become the Sunflower Revolution, but still. I came out alright. I recall being surprised that I hadn’t even been scratched—even after having charged a police barrier.

It began with the student group which I had been hanging out with for the last several months or, we might as well say, had adopted me as their foreigner member. The president of that group, L.R., had wanted to attend a discussion on tactics and strategy at Cafe Philo within their Facebook group. I figured I would attend.

Another member, Q.L. cut in that point in the discussion, citing the need to attend another event on a college campus near the Shandao Temple area. It wasn’t very clear what that other event was, but she kept pushing the point, stating that it was absolutely necessary to attend this event, not the tactical discussion. She managed to convince the rest of the group into. So I showed up, thinking it was a protest or some other general demonstration and met up with the ten to fifteen people of our circle of friends.

I won’t name the location we met up at. There’s little point to hide it at this point, actually, since everyone knows it, but I still want to err on the safe side. Let’s just say it was a location on a college campus near the Legislative Yuan that had been put together by a group of students to serve as an off-site staging ground for actions a few days after the occupation. Anyone who had a student ID—even an international student like I myself with an international student ID (though I usually had people to vouch for me, if need be)—was allowed in. You can bet there’s no way that there weren’t undercover police there.

HONESTLY, EVEN AT THIS POINT, I’m not sure who exactly the planners of the attempted Executive Yuan occupation were. Well, I have some idea, actually, and I know where to look. But I also think it’s probably a good idea that until this is all dead history, that their names remain in the dark. A number of them are not willing to speak at present, though I certainly tried to seek them out, because this remains controversial just within Taiwanese activist circles. Many activists still do not think that the attempt to seize the Executive Yuan pending the Ma administration’s lack of response following the Legislative Yuan occupation as a way to force a response was justified.

What I can tell you is that the majority of the participants in the Executive Yuan did not know of the plan beforehand. Everything was kept under wraps. The person who had called all of us there did not know the plan until several hours beforehand either, I found out later. The majority of the people there in the staging ground did know beforehand, for most had been pulled there through friend groups and networks. A lot was done through person-to-person contact and through deliberately cryptic communication on social media. We know organizers’ phones were being tapped, to say the least.

Photo credit: 323行政院反服貿公民

Photo credit: 323行政院反服貿公民

This secrecy was, of course, also a matter of controversy. For the record, though, I don’t think this was unjustified. Sometimes you’ve just got to do what you’ve got to do. That’s what being an activist calls for sometimes—much less being a revolutionary.

AT THE STAGING GROUND, which had about three hundred people on site, we were split up into five man cells, which were to exchange phone numbers. We also all wrote down our phone numbers in order that we could be registered into a mass texting system. We also left our stuff there. You can’t charge a police barrier carrying a heavy backpack, after all.

There were three different teams, one which was to charge the front door of the Executive Yuan, one which was to charge the side door, and one which was to charge the back door. Each team was approximately fifty people, each of which had a designated leader. I and the rest of our group was part of the back door team. After preparations were complete, we split up. We were to meet at a designated site near the back door of the Executive Yuan in order to charge at 7:25. We split up and went for food after that, though if memory serves we just got convenience store food. Can’t fight on any empty stomach, no? But I recall just buying a piece of bread, because I anticipated having to run, and I didn’t want to feel sick. I wasn’t sure why, since this seemed logical to me, but everyone else seemed to find that funny.

We gathered at our designated site, which was a street corner maybe two hundred, three hundred feet from the back door. We were the first to arrive. Q.L., who had called us all there, made us all huddle along the corner of the wall, so our presence would be less visible to the police outside the backdoor. But as we did so, I noticed a large bus, full of riot police, drive by.

As we were huddled on the side of the wall, I ended up talking to B.T., another member of the group, as he and some others were talking about whether the police knew about our plans or not.

“What do you think are the actual chances for us succeeding here?” I asked him. Well, obviously I no longer remember my exact words. “You saw that, right?” I said, referring to the bus.

“Probably not a lot. Maybe we’ll all be arrested in a short while,” he said. I was impressed by how calm he was, saying that.

“There’s no way the police didn’t know about the staging ground,” I said.

“Through monitoring social media or e-mail?”

“Undercover police,” I said. “I don’t know about the Internet, but there’s no way there weren’t undercover police in that place. Anyone with a student ID was let in.”

WHY HAD I NOT backed out of this? I had been wondering throughout the set of circumstances. I had been caught up on the moment. There was no way to get out of this. Even citing that I was a foreigner who might be at risk of deportation I would have lost a great deal of face, I felt. And I realized that I was caught up in something genuinely interesting, no matter the risks.

I looked and saw L.R., the president of our group, pacing. Somebody had asked him when we would know when to charge and he was making a phone call to make sure. He got off the phone. “Somebody will come here and tell us when to charge.”

I don’t know how much time passed after that. During these kinds of things, the flow of time seems to dilate. I even had to check with others afterwards to make sure that someone had, in fact, ordered us to charge, that is, the leader of the back door team. I never saw who it was.

「警察!後退!警察!後退!」。 Film: T.Y.

Suddenly we were in the streets, running. A few dozen students in the streets. Deportation was the least of my worries now. I was surprised by how light I felt, running in the streets then, sprinting with all my might. And then we were all pressing against the police with their riot shields, as all of us were thrust up against the police, trying to push them back. The rest is all a flash in my memory.

「警察!後退!警察!後退!」

I was stuck somewhere in the middle. The left flank was collapsing relatively, it looked like the people on the left were going to be crushed. I began screaming out: “To the left! We need more people on the left!”

“We kept pushing, but I noticed that the police weren’t budging.” Film: T.Y.

I don’t think anyone ever heard me. The automatic gate began shutting, but I was too far in the back of the crowd except to register the sight of the gate itself, only the noise of it shutting. I was suddenly pushed up against yet another member of our group I had never really talked to before, side-by-side, trying to force back the police, others pushing against our backs and us pushing against the backs of those ahead of us. Though I did not notice at the time, I would later here that several people were injured when the automatic gate closed on them, though I don’t know how badly.

We kept pushing, but I noticed that the police weren’t budging. I slackened my effort somewhat then, maybe. Reviewing the video taken by our friend T.Y., who was pushed out of the initial charge early on and then decided to take video when he couldn’t insert himself back into the charge, it clearly wasn’t just me. There seemed to be several waves in which we as a group were slackening in our efforts to push back the police because of that it seemed to be no use, then renewing our efforts.

“It seemed without warning that the police were suddenly behind us.” Film: T.Y.

It seemed without warning that the police were suddenly behind us. I’m told this was only five minutes after our charge had begun, but time itself seemed not to be a factor at that point. Looking at the video, there’s no surprise at all to that the police under siege at the gate would call for reinforcements.

I ended up being ejected from the center of the crowd. I assumed a look of not really understanding what I was doing, a policeman shoved me aside, and I ended up in the surrounding crowd of bystanders who had gathered since the beginning of the charge. With the number of people around the protest site every night at that point in time, our charge had attracted attention from crowd. As some of the surrounding bystanders were also students, I blended in.

Shortly after I had been forced out of the crowd, Z.S., a member of the group I was pretty friendly with, was also forced out. I pulled her towards me. According to T.Y., who was observing on the side at this point, still filming, 6-10 people were pushed out around this time, though this number is hard to judge because of the number of surrounding bystanders.

I remember being frozen in shock for several moments as, now, between Z.S. and myself, we were caught, alone, while a throng of police had surrounded the rest of our friends. We were cut off from our friends and I had no way of knowing what had happened to them. Had they been beaten up by the police, were they okay, were they hurt? Those were the kind of thoughts that ran through my head.

“Lie down! Lie down! Lie down!” shouted Z.S. at me. A number of the students that like us had been forced out, were lying down on the ground front of the riot police having surrounded our compatriots. Shrewd thinking, whoever it was had thought of the idea.

I lay down next to her, linking arms with Z.S. on my left and a girl who laid down next to us on my right who I wasn’t acquainted with. In the tension of the moment, Z.S. began crying, leaving me unsure of what to say for quite some time, but while the tension of the moment did not fade, we eventually returned to a jocular atmosphere.

From then on, it was a waiting game. I’m honestly not sure how long we were waiting there. I think more than an hour. With us lying down on the ground, the riot police, now having formed a ring around our friends, had arranged themselves back-to-back so that policemen were facing both outwards—towards the gathering crowd—with their riot shields but also inwards towards our friends. But they couldn’t leave, because they would have to trample us to get out. And because we had been so quick as to block off their path of escape, this made it possible for a growing crowd to prevent the police from leaving altogether. The resulting standoff at the back door of the Executive Yuan would last for close to three hours.

The back door of the Executive Yuan. Bolao is the individual lying on the ground furthest to the right in this picture. Photo credit: Set News

The back door of the Executive Yuan. Bolao is the individual lying on the ground furthest to the right in this picture. Photo credit: Set News

We weren’t on the ground for the entirety of the time; eventually people began to trade off places and take shifts. There are some funny stories from around this long period of time.

There’s a story about a male student, a friend of a friend, who ended up grabbing hands with a girl lying down on the ground in front of the police, finding the sound of voice very attractive and her hand very warm, but in the end never getting to see her face.

At one point, an elderly lady who seemed to have a heart condition arrived and insisted on switching with the girl who was on my right in lying on the ground, despite my continually urging her that she not do so because of how evidently poor her health was. She was eventually persuaded to leave.

More than one Taiwan Independence Referendum Alliance turned up during this time, with ladders ready to scale the back door and make their way into the building through windows. At least several managed to get in and for a brief while there was a small scuffle between students trying to protect the TIRA members and the police who were trying to pull down the ladder even as there were people climbing it. Eventually the police seized the ladder.

X.X., another one of our group who wasn’t present in the initial charge showed up around 9 PM, having called our the president, L.R., after hearing about the events and wondering where we all were. Well, L.R. had told her that we were at the back door of the Executive Yuan, but what he hadn’t explained for some reason was that a number of us—including he himself—were surrounded by police and had been stuck there for some hours. I also recall hearing L.R. suddenly screaming at the police, “In the annals of history, it’s you who will go down as the criminals!” as he was being dragged away by the police during the initial charge.

It was a little before ten PM that the police finally broke up their cordon and let our friends go. Apparently, the decision had been made that the situation was becoming too dangerous with the crowd for them to protect their safety. So, in the end, our friends were let off the hook—none of them were arrested. We were lucky as hell. I believe the people surrounded by the police were released in two blocks, with a larger group being released first, and a smaller group of 6-9 people remained entrapped by the blockade for some time longer. The difference in timing between these two releases, I no longer remember, however.

We were called back to the staging crowd by text message. The text wasn’t clear, but it just said to return, and was a mass text that went out to all of the participants in that night’s actions. Some of us actually ran back, thinking it was an emergency. The rest of us walked back, found that there was no real emergency, and no real plan except a general call to regroup. We decided that we wanted to see the front of the Executive Yuan, so we went back.

I had to corroborate the story with someone who had been on-site in front of the Executive Yuan later, directing traffic, but who hadn’t actually been part of the charge itself. The charge in front of the Executive Yuan had succeeded in breaking through the barbed wire police barriers in front of the Executive Yuan, some climbing over by placing towels on top of them, and then eventually forcing apart one of the barriers.

Members of the front door team had managed to get in around 8:30, spilling into the second floor, to the extent that it became a problem that too many people were trying to surge in and many of the protestors that had been hanging around the general Shandao Temple area were now in the Executive Yuan courtyard. We ourselves had seen one of these occupiers at the back door around 9:30, when he became visible through a window to much fanfare. When we were in the courtyard of the Executive Yuan it was just past 10:30 and police were blocking off the entrance to the Executive Yuan, but the courtyard was full of a mix of protestors and members of the police attempting to get protestors out, though not yet using force. It was only later that protestors would try to force their way past these police into the Executive Yuan once again and the use of police violence began.

It looked like something more like a war zone than an attempted occupation. To make it in and out as a group, we had to link arms and weave through the wreckage of barbed wire barriers. I remember seeing some banners that had been thrown up, but, again, it looked more like a war zone than an occupation. But seeing as there wasn’t anything we could really do, we went back to the staging ground.

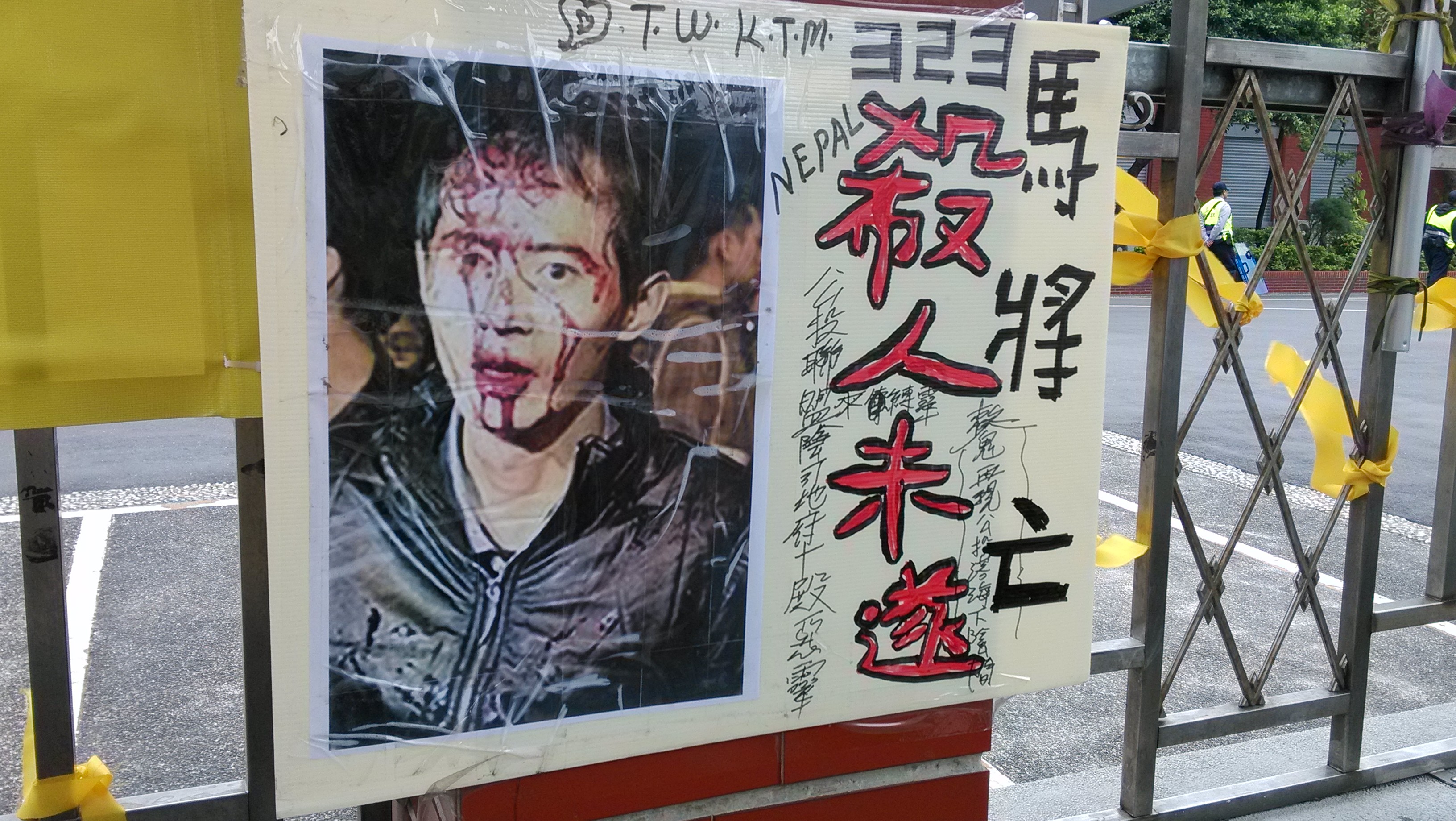

THE POLICE VIOLENCE and the use of water cannons that the night is remembered for began at half past midnight. At that time, I and the others were discussing the night’s events in the staging ground, but it was me who first noticed the notifications on Facebook about police violence when that now infamous picture of the man with a bloodied face began circulating on Facebook. I’ll probably never forget what L.R. said immediately afterwards:

“Well, it looks like the monster which hasn’t shown its face in twenty years has returned.” Photo credit: 王顥中

“Well, it looks like the monster which hasn’t shown its face in twenty years has returned.” Photo credit: 王顥中

“Well, it looks like the monster which hasn’t shown its face in twenty years has returned.”

We waited around for some time to keep track of ongoing developments, contemplated going to the site of the Executive Yuan itself, and tensefully debated whether going there would have any actual effect on changing the course of events except getting ourselves hurt. But as there wasn’t much to do, we broke up, vowed to keep in contact, and to plan future actions. I took a taxi home.

I WENT BACK the afternoon of next day. Strangely, one of the first people I encountered was old man with a shock of white hair in the background of the iconic photo of the man bleeding from his face, who was for some reason still standing in the same place he was standing during the preceding night. But I was struck, appalled, by how empty it was around the occupation site.

One of the reasons I hadn’t gone to the Executive Yuan site after the use of police violence began was because I agreed that I would not have any ability to change the course of events and very probably, after all the risk I had gone through that night without getting injured somehow, I would have just been asking to be beat up. I recall chatting on Facebook with one of my New York City activist friends while idling at the staging ground, saying something like, “Yeah, police violence has begun, it looks like the occupiers at the Executive Yuan are being evicted. But rest assured, there will be tons of people on the streets tomorrow.” That was me evaluating Taiwan by American standards. Of course, it didn’t happen.

Front gate of the Legislative Yuan, several weeks after the attempted Executive Yuan occupation attempt. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Front gate of the Legislative Yuan, several weeks after the attempted Executive Yuan occupation attempt. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

What, of course, shocked me more was the public reaction thereafter. While in truth, the amount of violence which had taken place at the Executive Yuan the previous night is comparable to the amount of violence by used by American police against protestors at, say, G8 summits every year, this was probably still the largest concerted use of police force since the Martial Law era. Yet public reaction had sided with the police.

The echo chamber of those clamoring online was a frightening thing to behold. The protestors had deserved it! And I would even see online commentators praising the actions of police, blow-by-blow, as they lashed out against protestors with batons, fired tear gas, or blasted them with water cannons. How horrifying it was, to see such joy in violence! And against students, young people, traditionally held to have a “pure” role in Taiwanese society to the extent that the Sunflower Movement student participants took on dimensions of martyrdom! This was apparently the inverse side of that, that students could apparently be beaten with impunity, and it was the man on the other side with the baton was the one to be praised.

IT IS A QUESTION as to whether the Executive Yuan occupation was a success or failure. What it did manage to do was to attract the attention of international media in a way that the initial Legislative Yuan occupation hadn’t. Since it’s blood which draws the attention of media, of course.

But even within activists themselves, the events of that night remain controversial. When I was talking to protestors around the Legislative Yuan site two or three days later, asking them how they felt about the Executive Yuan occupation, most of them stated their disapproval, and that police were justified. Why?

“Because it wasn’t our space,” said one man I asked, shaking his head.

I felt like throwing up my arms in frustration! What a vague, pointless answer! Even some of the people I knew within the Legislative Yuan disapproved of it.

Apparently within the standards of morality, it was deemed illegitimate that the Executive Yuan was premeditated, whereas the Legislative Yuan occupation was apparently spontaneous—although in fact, I have to doubt that it truly was. It may have, in fact, been lucky that the Legislative Yuan occupation and the attempted Executive Yuan occupation became disentangled in the media, so that the Legislative Yuan occupation and the Sunflower Movement did not become discredited in the eyes of the public.

Despite the general valorization of the Sunflower Movement by the public in the present, this remains so. Almost nobody I involved in the Executive Yuan occupation attempt that I did not know personally was willing to speak to me for this article. Moreover, I will just freely admit there are things I know of that I am not reporting on, because apart from the standing legal trials of individuals I do not want to see harm come to, that this is still controversial and potentially damaging to future organization requires I play dumb and deaf whereas certain things are concerned. I can understand that, but there were other things I did not want to turn a blind eye to.

One need only look at the current Jiang Yi-Huah trial to see that the issue of the violence used that night hasn’t just faded away into nowhere. But I also feel as though the events of that night are being slowly buried. There is much I just can’t confirm, because my picture is just too incomplete. For example, a Taipei Times article published that night claimed that three of the five yuans had been occupied for the first time in Taiwanese history, that is, including the Control Yuan. I recall hearing an announcement that a group of Indigenous students had occupied the Control Yuan sometime during the night in the staging ground.

Yet I never heard anything about the Control Yuan occupation afterwards. Eventually a story emerged of fifty Indigenous students that became confused and went to the Control Yuan, rather than the Executive Yuan, maybe in the same way that some movie star went to the C.K.S. Memorial rather than the Legislative Yuan during the night of the initial occupation. But whatever happened to them? I could never find out, there was certainly nothing about fifty Indigenous students being arrested in the news, Chinese or English.

Hell. It was difficult enough sorting out the accounts between the three different teams that attempted to charge the Executive Yuan. Although most visible was the front door charge, the incident at the back door also made it into the news. I even recall seeing pictures of myself lying on the ground in front of police in the news. Yet the existence of the side door team has been nearly forgotten about entirely, there are even participants in the charge that weren’t aware of its existence.

Was the Executive Yuan Occupation Justified? Was it a Failure?

ONE CAN PUSH, but sometimes society at large will be afraid of change. There is something called “fear of freedom.” It is always a struggle against the quotidian, the everyday, the commonplace morality of society. Is the solution, then, to force people to be free? I mean, when you look at the Executive Yuan occupation, half of the people involved had been pulled in, without much in the way of prior knowledge as to the consequences. And the idea with that occupation was to galvanize society writ large, given the impasses of the Ma administration in refusing to respond to the Legislative Yuan occupation and refusing to meet with students.

I don’t know. Honestly, I’ve struggled with this question a long time, personally, and in not just this context. But I will say this: I do think, in some sense, that what we were trying to do that night was heroic. I’m not going to judge as to whether it was justified or not. Without being self-congratulatory, sometimes it requires individual egos willing to go against the tide for any change to happen in society. Perhaps what we need are more of those willing to be enemies of the people, for the sake of the people.

In fact, can we conclude that the Executive Yuan occupation was a failure? I’m not so sure. People are still unwilling to talk about the events of that night. Had the Legislative Yuan occupiers, for example, thrown their weight behind the Executive Yuan as it happened, it probably is not incorrect that that would have led to a discrediting of the Sunflower Movement as a whole. I suspect we were lucky. But we did eventually see a response from the Ma administration, albeit one which remains rather ineffectual, not to mention tone deaf.

Would we have had that without the Executive Yuan occupation attempt? Probably. But that was also the first time major international media were attracted to the Sunflower Movement—attracted by the scent of blood and garbling many of the most basic details about Taiwanese politics—yet nevertheless an accomplishment.