The past three months of protest across East Asia

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Brian Hioe

WHILE AS USUAL the western world pays little attention, it would seem that Asia is in the streets these days. Three months have passed since Taiwan’s Sunflower movement sought to address issues of Taiwanese internal democracy and Taiwanese sovereignty vis-a-vis China, with the storming of the Taiwanese Legislative Yuan for the first time in the nation’s history. With the revival of Hong Kong’s Occupy Central in new form, sovereignty issues regarding mainland China and questions of democracy have generally taken center stage whereas Chinese speaking countries and territories on China’s periphery are concerned. Less discussed in connection with Taiwan and Hong Kong is the recent Article 9 controversy in Japan against the repeal of Japan’s Article 9, which in the past few days has seen the largest mobilizations in Japan since the height of the post-Fukushima anti-nuclear movement two years ago.

In regards to these disparate protest movements, among the various activist communities spread across East Asia, there has been a shared sense of a solidarity between the different social movements that have sprung up in Asia during the past several months. For Hong Kong and Taiwan, it is easy to see why; after all, Hong Kong and Taiwan both face is the very direct threat to internal democracy coming from China. For Taiwan, Hong Kong represents a possible future that it would like to avoid, and for Hong Kong, Taiwan’s Sunflower movement certainly offered an inspirational show of resistance to China.

But, indeed, though Japan is not a part of the Sinosphere, to the extent that the present author has longstanding connections to Tokyo-based activist networks, there was much interest from Japanese activists and organizers in particularly the Taiwanese Sunflower movement. Though the protest of over 40,000 in Tokyo against the repeal of Japan’s Article 9, a post-World War II constitution article which bans the waging of war outside its borders by Japan, would not seem to be immediately connected to Taiwan and Hong Kong, activists from both Taiwan and Hong Kong nonetheless took interest in what was happening in Japan. For activists in popular movements resisting authoritarian regimes of government, there was a sense of kinship, whereas the repeal of Article 9 was militated for by far-right Japanese ultra-nationalists and stirred up a widespread popular outcry from the Japanese public at large, especially after the self-immolation of a Japanese man in his 50s or 60s in Shinjuku in protest of Japan’s “return to fascism”.

So, then, is there a general shared sense of mutuality between social movements in Asia, founded on a sense of shared sympathy and maybe a vague sense of a shared enterprise. What we might seek to do at present is to point to the deeper, structural causes behind why three protest movements would emerge in Asia in roughly the same timeframe. Because in the author’s estimation, the problems addressed by all three movements stand little chance of resolution without a transnational or international politics across Asia. What lurks behind all three movements is the same specter which has haunted East Asia for close to seventy years: the specter of the Cold War. Or, more precisely, agitation over an increasingly aggressive China and the geopolitical strivings of China and America in East Asia which persist to this day.

IT IS NOT PARTICULARLY NECESSARY to point out to what extent China’s foreign policy encroaches upon Taiwan, in regards to China’s claims to Taiwan, and the threat of Chinese annexation of Taiwan through military means—or economic, as in the case of the CSSTA trade bill that was opposed by the Sunflower movement. Likewise, as since the British ceding of Hong Kong to China, Hong Kong has stood in uncertain relation to China as possessing a more democratic form of governance than China by legacy of British colonialism, but now having become a territory of China.

And as China seeks to increase its influence in the region, it likely views resolving what it considers to be internal matters as necessary for future external growth, to the extent that it views the Chinese speaking countries on its periphery as subject to its central authority. Despite passing through a period of purported Communism and some undefined form of capitalism characterized by a strong, authoritarian state retaining its central economic planning capacities, the notion of China as defined in civilizational terms remains a rationale for justifying Chinese authority over other Chinese speaking nations and territories in East Asia even when their history has been separated from that of mainland China, in some cases, for close to or over a hundred years, that is, for most of Asian modern history.

Nevertheless, when we turn towards considering Japan, we might contemplate the forces behind the repeal of Article 9. An integral part of the Japanese constitution after World War II, Article 9 restricted Japan from waging war, as a result of which, while Japan possessed a militarily advanced “Self-Defense Force,” Japan was forbidden from waging war even in order to counter threats. While the repeal of Article 9 is driven by right-wing conservatives that long for a return to a dreamed golden age of Japanese imperial power, one might also turn towards considering the rationale by which the need for Article 9’s repeal is justified. That is, to counter increasingly proactive Chinese territorial aggression by Japanese hawks and rightists, Chinese territorial aggression justifying increased Japanese use of force.

Here we find a twisted form of symmetry. Whereas Chinese territorial aggression is motivated by the political imaginary of an ahistorical civilizational China, whose claim to Sinosphere nations and territories is justified under civilizational auspices, future Japanese territorial aggression, like past Japanese aggression, would be justified on the basis of Japanese civilizational supremacy as bringing enlightenment to other East Asian peoples. Because while Japanese imperial dreams of “Pan-Asianism” are long dead and buried, what remains is the notion of an ahistorical Japanese civilizational supremacy which, of course, finds a twisted parallel in notions of similarly ahistorical Chinese civilizational supremacy.

Occupy Central in Hong Kong. Photo credit: South China Morning Post

Occupy Central in Hong Kong. Photo credit: South China Morning Post

But where one might merely decry the logic of ethnocentrism or essentialist cultural supremacy or merely view Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan alike as up in arms over fear of China, here we must turn towards evaluating the origin of the contemporary arrangement of powers in East Asia. Whereas during the era of the Cold War, China was largely viewed by western powers as a Communist nation in alliance with the Soviet Union, largely ignoring the Sino-Soviet split after 1956, the East Asian capitalist nations are and have always been largely shaped by American power in the region.

ONE MUST REMEMBER which nation it was it was that instituted Article 9 to begin with in order to keep Japanese military power in check after World War II, even as Article 9 later would become a point of pride for many Japanese as a symbol of a pacifistic national renunciation of war. Similarly, one must remember which nation it was that propped up Taiwan’s claims to be actually legitimate China for so many years in order to counter Communist China, even as the KMT’s actions during the Taiwanese martial law period flagrantly contravened claims that Taiwan was a bulwark of democracy against undemocratic, Communist China.

It was, of course, the United States. While American response to the Taiwanese Sunflower movement or Hong Kong’s Occupy Central have been limpid, except for the same usual, rhetorical gestures towards “democracy,” whatever that means exactly, it is by no means that America is not paying attention to East Asia at present. Hardly. Though one cannot expect omniscience from American foreign policymakers either, whereas Asia is a significantly determining sector of the world, one can count on America’s eyes to be set on maintaining what it views as the regional stability for the sake of maintaining what it views as overall global stability. Yet as always, America will attempt to keep its stances as ambiguous as possible for the sake of strategic indeterminacy—so as to keep America’s potential enemies in the dark about what potential American action might look like in order that America’s move set is maximized and its “enemies” are unable to determine future moves.

Anti-nuclear protest in Tokyo, Japan in July 2012. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Anti-nuclear protest in Tokyo, Japan in July 2012. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Because though America might now be shifting to a more aggressive foreign policy in East Asia aimed at keeping China’s growing power in check, the so-called “Asia Pivot” that would apparently be the crown jewel of the Obama administration’s foreign policy achievements in East Asial as Japan is a longstanding client state of America at whose behest, then, it is the US to whom it be that a repeal of Article 9 would be beneficial. Obviously, the relation of the Japanese ultra-nationalist rightists drumming for the repeal of Article 9 to America is ambiguous, but through the twisted logic by which those most visibly anti-American are often those most dependent upon American backing for their continued existence, there would seem to be little other short-term option for Japanese ultra-nationalists but to draw closer to America in order to sustain or spearhead an increase in Japanese regional power. And so does America find itself once again backing questionable far-right wing forces in East Asia for the sake of its larger vision of regional stability, as with Taiwan and Japan alike after World War II?

It is, of course both ironic then, that so many Taiwanese of general Left-liberal to moderate political orientation find themselves cheering on Japanese protestors opposed to the repeal of Japan’s Article 9 to the degree that many mitigate for measures such as the addition of Taiwan to the Asia Pivot in order to counter growing Chinese aggression. After all, resurgent Japanese militarism and a stronger Japanese role in the Asia Pivot may be the force necessary to counter growing Chinese power in the region, even if, of course, there may be longer term blowback. Yet, from the standpoint of balance-of-power realpolitik in foreign affairs, this is the logical move to counteract China—even if it means backing questionable, pseudo-fascistic Japanese politics. One wonders how Hong Kong, of course, now permanently wedded to China, will cope, but for Taiwan, this would certainly be the “rational” foreign policy move through such a lens of consideration. One can even speculate as to an international politics between Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China in some form founded upon agitation over Chinese power.

Indeed, this makes sense. China is economically powerfully, militarily powerful, has political pull in the region, and cultural recognizability. By contrast, Taiwan is economically strong relatively speaking, lacks military power, has weak political pull through its general lack of national recognition, and lacks cultural recognizability—one must only consider the rapid extent to which Occupy Central recently became more internationally known than the Sunflower movement through Hong Kong’s relative cultural fame relative to Taiwan. Hong Kong is also economically significant relative to its surrounding region, has zero military power, has weak global political influence of its own, but cultural pull. And, finally, Japan is economically powerful, militarily powerful if not having been strait-jacketed for so many decades, has actually rather weak international political influence, but possesses cultural significance. To the extent that Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan (and, for that matter, Korea) alike pale in the comparison to the mammoth nature of China, it would be to the benefit of all to geopolitically align under American auspices to counter China, whereas no other force in the region could probably unite them given the rocky history between these countries territories in the past.

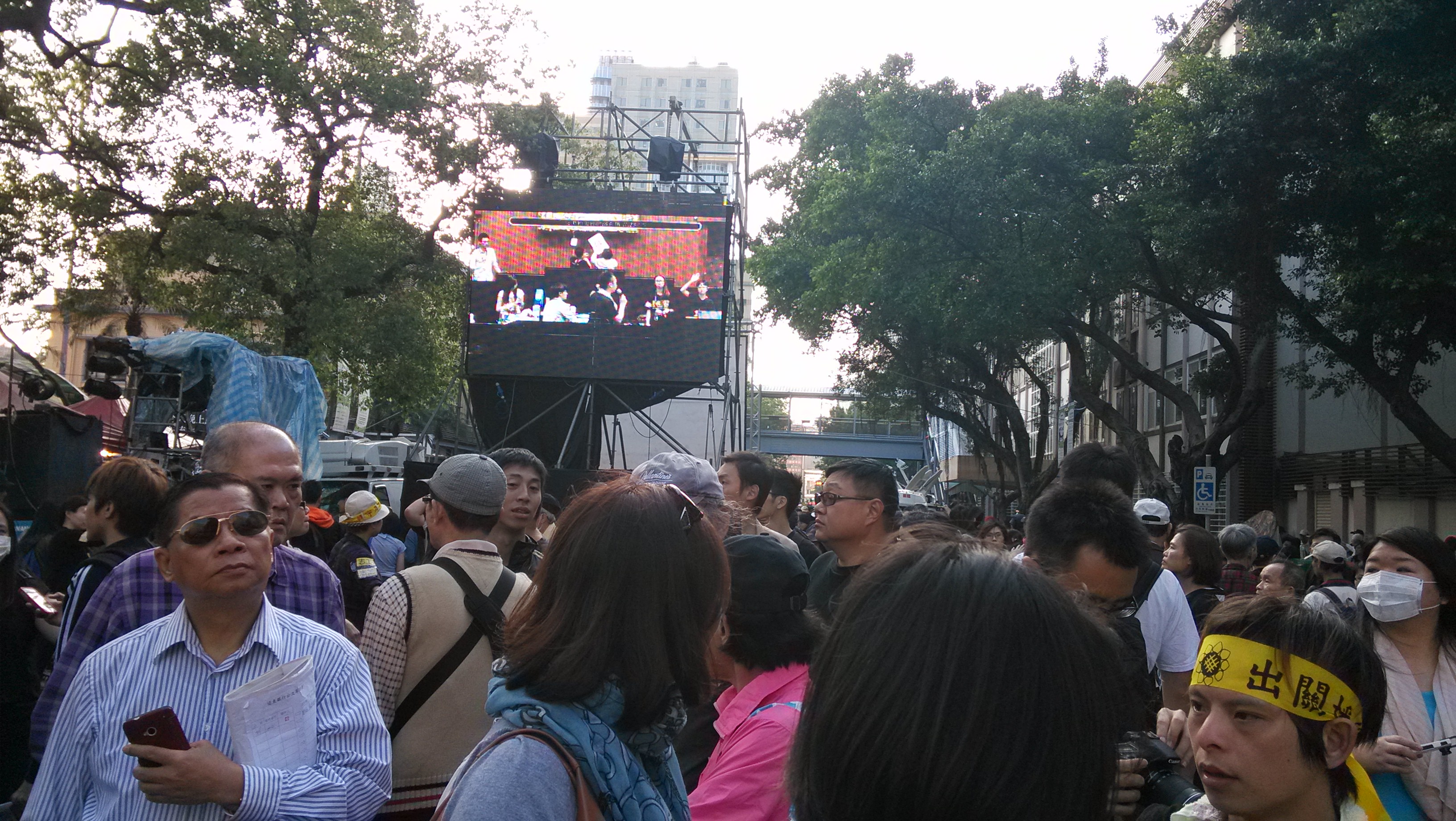

Protestors in the vicinity of the Legislative Yuan. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Protestors in the vicinity of the Legislative Yuan. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Nevertheless, one can also speculate as to the limitations of such a politics to the extent that such a politics will have to take on an anti-China and, of course, traps us within the parameter of regional geopolitics that will then necessarily persist for decades. And so the specter of the Cold War would only retain its grip upon present day reality.

BUT FOR THOSE OF US who have not given way to such cynicism, for those of us whose definition of political action is not limited to purely electoral politics or the military actions of nation-states, let us place our bets upon the possibilities of a transnational politics which can transcend the limitations of such geopolitics.

The point precisely is, of course, that such a politics does not exist in the present. Whereas different activist communities through a vague shared sense of the situation might sympathize with each other, a politics of solidarity and merely offering sympathy across international borders is not enough. A transnational politics must be organized at a fundamental level, of course, the structures to do so just simply do not exist in the present.

Yet, if a transnational politics is to be coalesced out of disparate East Asian territories, what it would be founded on is probably the shared condition of East Asian politics, that is to say, the degree to which the indirect geopolitical conflict of China and America has become an underlying condition of East Asian modernity after World War II. Whereas Hong Kong diverges because of its history of British colonization, Japan and Taiwan share the commonality of having been governed by one-party regimes backed by the US after World War II, a history of authoritarian rule, restrictive, selectively reporting news media backed by corporations, the presence of longstanding, powerful political families within the former ruling party, and the presence of ultra-nationalist far-right elements, often with ties to organized gangsterism, within the political spectrum—even if, of course Japan never saw anything comparable to Taiwanese martial law (although Korean military rule is more closely comparable). But, on the other end, what is shared between Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan alike is the formation of a culture of politically progressive young people participating in activist politics in recent years operating within an environment characterized by a largely apathetic public who passivity is sometimes maintained through an instilled puritanical sense of public morality and respectability. Where Hong Kong differs, that democratization was actually only introduced into Hong Kong in the last ten years of British rule, nevertheless causes it to fit together with Taiwan, Japan, and Korea alike as having only achieved democracy within a relatively short duration of time roughly within the last two decades of contemporary history.

Accordingly, for all its vagaries, it might be, then, that democracy within Asia is what becomes the rallying cry for a future transnationalist or internationalist politics. What remains to be seen is how maximalist or minimalist the call for “democracy”—sometimes a term not much more than an empty signifier upon which almost anything can be projected—ends up being in terms of actual political outcomes. But so is call for mutual discourse, dialogue, and organization among activist communities in Asia a necessity beyond the exchange of mere pleasantries. It is not so hard. We live in the age of the Internet. Whereas language barriers are concerned, English has become something of an international language. And, for one, all these locations are a mere plane flight away—and in a funny coincidence which at least the author thought to be providential, to fly from Taipei to Tokyo or vice versa in fact usually demands a layover in Hong Kong, mimicking the chronological spread of protest events thus far. Yet perhaps the future of Asia depends on the formation of such international networks capable of mobilizing and coordinating across boundaries and borders.