by Garrett Dee

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Front Cover

Ray Yeung is a director of Hong Kong origin whose films touch upon the lives of queer Asian men and issues related to coming out and cultural expectations. His latest film Front Cover centers around the character of Ryan (played by Jake Choi), a gay Chinese-American living in New York working as a celebrity stylist. Although Ryan is ashamed of his Chinese heritage and does everything he can to distance himself from it, this changes when he is assigned to work with Ning (played by James Chen), a handsome celebrity from Beijing doing a photo shoot in New York who is later revealed to be closeted. Over the course of of few days, a strong attraction develops between the men which forces them both to confront their buried insecurities surrounding culture and sexuality at personal cost to them both.

I spoke with Ray about his motivations for crafting this film and what he hopes audiences will take away from these characters’ stories. This is the first of a series of interviews on the film with the director and the lead actors. The film has won awards at several international film festivals and will be showing next at Angelika Pop-Up in Washington D.C. starting Friday, September 30, 2016 (showtimes can be found here). The film will be showing in Taipei at the Taipei Queer International Film Festival on October 22 and 30.

Garrett Dee: First of all congratulations on everything, you’ve gotten quite a few accolades on this film. Did you expect that going in?

Ray Yeung: Well, I think you always approach a project like an athlete going into a match; that is, you always expect to win, right? So there’s always an element of that, but basically I just have a list of things I want to achieve and most of them I achieved with this film.

GD: Could you go ahead and tell me about that list, what were some of things you wanted to achieve?

RY: I really wanted Strand—our US distribution company—to be our distributor. I’ve always wanted to work with them and I think they always have great films on their catalog. They approached us and said they were interested in distributing the film, so that was a big thing for us. Another one is the Hong Kong distribution company Edko, which is another company that has always been on my dream list of companies to distribute a film, so it was exciting to work with them.

GD: The film has already shown at several film festivals around the world. How has that experience been?

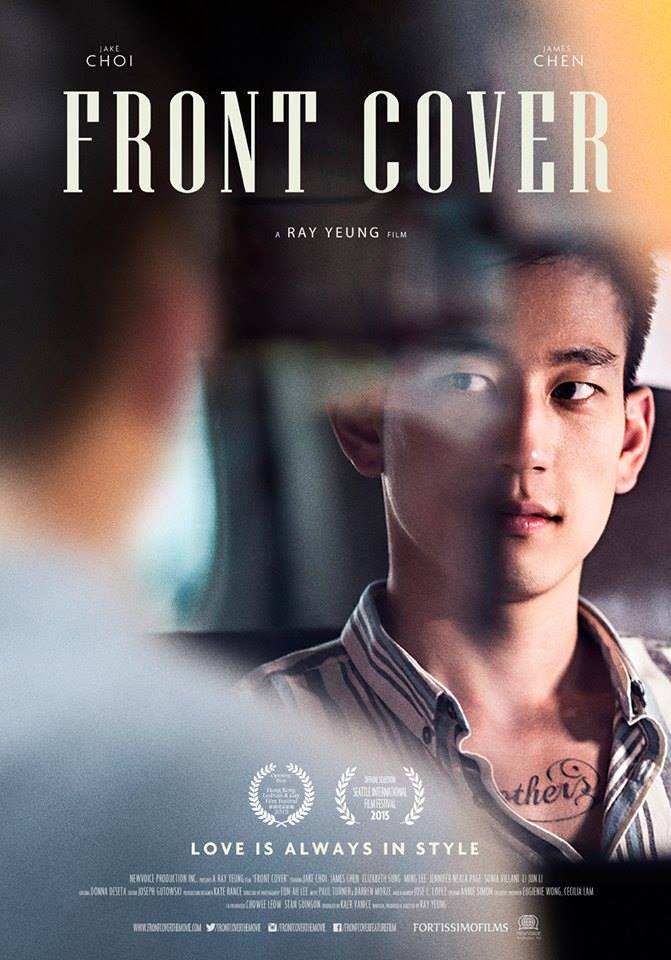

Film poster

Film poster

RY: Film festivals are always very good, and we have been invited to many film festivals. I think the main thing for me is the audience, and the most important thing is afterwards a lot of the audience members come up to me, and a lot of them are people from China who had moved to another country, and they say it was really the first time that they actually could hear people talk like them and have that kind of experience that they have had. That was very touching for me.

In fact, recently in Vancouver there was this boy who came up to me and he said he wasn’t out to his mother yet, but when he eventually comes out to her he hopes that she will say the same things the mother in the movie says. As he was saying that he started tearing up and it’s just very amazing that you can touch all these different people.

First of all, it’s great that there are so many people out there who have that same kind of experience that I had. On the other hand, my coming out was a long time ago. We come to the present and there are still so many people with so many issues, even with people who have come out and have issues about being Asian in the gay scene still today. You know, there is still a lot of discrimination within the gay scene itself. With all those issues, I think it just touches on a lot of people, that they didn’t feel like they had a voice or people that represented them. Being able to talk to people like that is a very good experience.

GD: These are characters that people can really relate to and can see representing their own lives. For you where do these characters come from?

RY: The character Ryan is partly closer to me because I grew up in Hong Kong and then I was sent to study in an English boarding school. I was in a school outside of London where all the other students were white and I was the only Asian kid. There was a lot of discrimination going on. I was only 13, and people would call me names and make Chinese music noises on a daily basis when they saw me in the halls.

So as a kid, what you do in order to fit in is to try to distance yourself from anything that is remotely Chinese. I would start lying to them and saying things like, “Well, actually we don’t really eat rice at home, that’s just a fallacy, it’s not really true” or “In Hong Kong, no one really rides bicycles. That’s in China and Hong Kong is actually British, not Chinese”. So I came up with all these things to try to blend in.

And then later on, after I came out, I went out in the gay scene where being Asian is not really seen as attractive. You know, the gay male sex symbol is always a tall muscular white guy with blonde hair and blue eyes, and we are nothing like that. Asian male beauty isn’t really considered, even nowadays. So it was tough, how can you really have any sense of confidence when you don’t really see your kind of image being represented anywhere?

Once again, for me to fit in was to not hang out with any Asian gay boys. I remember, you could go into a gay club and there would be a lot of Asians in the corner and we would joke “Oh, let’s not go near the paddy field”. There was that kind of thing so that you were apart from them. And of course, the only thing to do was to date a white guy, that would make you feel like less of an outsider; that was your ticket to be in the mainstream gay scene.

So with all those kinds of things I thought, “Wow, that would be really interesting to have a character with that kind of background and belief and put him in a situation where he meets someone from China, which is a very different place now from what it used to be.” The character Ryan, his family are old immigrants so he’s been completely Westernized, but the new immigrants from China they come to the West with a lot more confidence because they have the money, the power, the whole world is new to them. They think they can buy half of the world now. And so for Ryan to meet someone like that I thought would be very interesting, to see that interaction between them.

GD: So like you said, Ryan is based mostly on your own personal experiences, and maybe the personal experiences of people you know. Where then does the character Ning come from?

RY: Well, I mean it’s really on the other side of Ryan where I see that character, almost as a mirror opposite of Ryan. Ryan is ashamed of his heritage but is very proud of being gay, so it’s almost like the flip side of the coin to have someone who is very proud of his heritage, but who is really in the closet and to see how they influence each other. And of course, I know a few people who are in the industry who are gay and they don’t really want to let anybody know because they feel that as soon as people know about them then their career is gone. The few people who I know who actually have come out in Hong Kong, their career has really hit a certain stage, and they feel like they have already gained a certain success. So for them to come out, it’s okay because they feel that they’ve already hit the peak of their career. But for people who are struggling, who are still trying to be an action hero or romantic lead, being gay is difficult. It’s particularly difficult in China, though even in Hong Kong it’s still difficult.

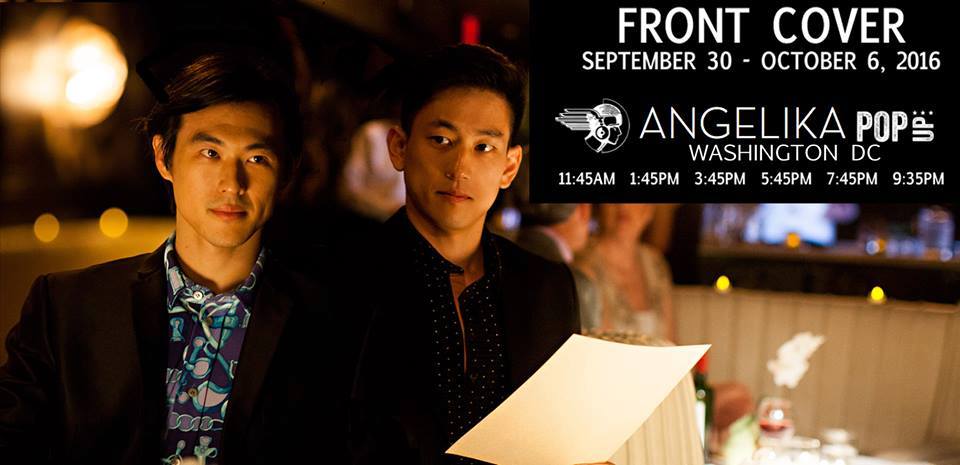

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

GD: You decided to set the film in New York. Why did you choose a Western setting instead of a Chinese one?

RY: Well, first of all I wanted to film it in a Western setting because I wanted to play with that old immigrant and new immigrant dynamic. I think that New York is an interesting place to be because it represents so much of the American Dream. It’s such a big range in such a small place. For example, Ryan’s parents come from Chinatown, which is only five minutes away from Fifth Avenue, but it’s a completely different world. No one ever says anything good about Chinatown unless it’s about the food. It’s always negative connotations about the people and the environment.

So for that journey, which is so packed into one place, I wanted to put the character of Ryan—who grew up in Chinatown but his dream is to be on Fifth Avenue—in that kind of setting. I think that just represents so much of not only the American dream but almost every immigrant’s dream, which is really just to climb up the ladder. Also, I wanted to get the character Ning out of China so that he would have a chance to really experience something different. It would have been really hard to get him to open up the way in a place like China where he was already well known.

GD: What were some of the biggest difficulties you encountered while making this film?

RY: The thing is, actually making a movie is not that difficult. It’s difficult in the sense of casting because you basically have to see everybody. None of that actors that I met was it just a matter of looking at their resume and thinking they could do it because you’ve seen their body of work. Most of them didn’t have any experience, or their experiences were as waiters, gangsters, or whatever. The casting took a long time because very rarely do they have the chance to get a role that is three-dimensional as Asian actors, so you have that hurdle in finding the right people.

A lot of times with an indie movie you can get a famous actor to come in and do a cameo in order to help to give the movie a little bit more visibility. Of course, there are hardly any Asian actors who are famous, so it’s really hard to get any help there. There are really only one or two people out there who have a name. If you’re an independent white filmmaker like some of my friends, they are able to get at least some kind of TV star to be in it because the pool is so much bigger.

GD: So what was it like to decide upon these two actors [Jake Choi and James Chen]?

RY: With Jake, the guy who plays Ryan, he just came in and there was just something about him. He’s very natural in the way he does a scene; it comes across like he’s not doing a scene at all, but he’s just talking to you instead. He’s not actually gay, but he had worked in a gay bar for many years as a barman so that’s how he kind of got to know the kind of character we were looking for.

James was completely different, he went to Yale and when he came in he was very flexible. He has a lot of technique and so I was considering casting him as either Ryan or Ning because he was so versatile. We put them and a list of other actors together and just tried the chemistry, and in the end it was just that James and Jake’s chemistry was the most authentic and most genuine, so therefore we decided to go ahead with those two as the main leads.

GD: You know at the heart of this film, despite the fact that it’s about two people who share a heritage, it’s also a romantic story between two people of different cultures. Do you feel like your own thoughts on cultural differences are expressed in the differences between the two?

RY: Yes, I think it is reflected. Partly because, growing up in Hong Kong, you are already in a cross-cultural environment. We are of Chinese descent but it was a British colony, so we were educated in an English way. At the same time, our families still retain a lot of the Chinese traditions. We are constantly having this contrast of different cultures, so it really represents my self. I was educated in the West, but yet I came back to Hong Kong for holidays and immediately I would change. I would be jumping from in England being very British and then go back to Hong Kong and be very Chinese, so all of that was always happening in my life anyway. I think all of that goes into this movie, and part of that, with the Ning character, part of the Chinese and the Ryan is part of the me in the West. It’s kind of like a contrast and a conflict.

GD: You mention China being very different now from what it was in the past. There’s a line in the film where Ning says to Ryan that he wants to represent the “new China.” What does the “new China” mean to you?

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

RY: The movie has actually been shown in China, mainly through the US embassy, which has picked up the film and done some private screenings. And all the people who come, a lot of them are very open about it. They are no different from people who have been educated in the West or anything like that. Taken, those people who would go to the US embassy are quite Westernized anyway. But, in general, a lot of ordinary people who live in the cities are quite open to this kind of thing.

It’s only when they get together and they want to make changes that it scares the people in control who are not wanting any changes and still wanting control of things. That is when the issues start. The mainland Chinese government is quite happy to let people do whatever they want to do to a certain extent, but when that starts becoming a force starts demanding some kind of change, that is the point at which they want to stop it. They just don’t want anything to be more popular.

Again, the Ning character is quite interesting for me. He’s someone who has a lot of ambition, a lot of dreams, someone who really wants to make a change in this world, or in China at least. And he’s willing to sacrifice his own personal freedom in order to make that change. When someone has that kind of ambition, his own personal happiness may not be the priority. I think when Ning says he wants to represent the “new China”, it’s the ideology of the younger generation, the people who want to make changes.

GD: It’s been the case in the past that a lot of queer film or Asian film in Hollywood have been considered niche films. Those kinds of ideas about who goes to see these kinds of films and what audiences you’re appealing can be limiting. How do you want to get this message out to a large audience?

RY: I think this sort of attention about the underrepresentation of Asians should have happened twenty or thirty years ago. It’s very late now, it should have happened all those years ago when Miss Saigon cast a white guy on Broadway and people were fighting about it. At that time, people thought they were going to change things, but nothing has really happened. There was a little bump but then everything just fell back. I honestly don’t feel like that is something that we can expect other people to give to us. Asian-Americans need to step up and make some noise and just do it, and tell people that we want to be represented and we are going to do work and represent ourselves because, trust me, no one is going to give it to us.

I think Hollywood, it’s just that machine which would never endorse this kind of thing. With a film like this that is both gay and Asian, I’ve seen so many people just tell me don’t do it, it’s not going to work, no one will want to see it except you and your friends. That doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be done, and the only way you can change this is by doing it. If you listen to them, you won’t do it and then it doesn’t go anywhere. If at least you do it, then it exists and hopefully it’s good enough that it will draw more people to come and see it and then it will slowly change it around. But it’s not going to happen tomorrow, I know that.

GD: What has the reception for the film been like in Asia so far?

RY: Well, in Asia, actually we only just started. We did the Lesbian and Gay Film Festival in Hong Kong last year but it was only a couple of screenings, so it will be very interesting what it will be like going forward. We are releasing the movie on October 13. I don’t know how people are going to see it. I think maybe they are going to see it as a gay romantic comedy, but I hope that people will see more than just a love story and something that is interesting.

I think it would be interesting if people do come to see it, particularly for audiences in Hong Kong. In Hong Kong there’s this very anti-China sentiment at the moment, for several reasons, some of which are justified, some maybe not. Don’t forget that this was a British colony, so there was a lot of residue coming from that. A lot of people have a different kind of way of thinking and a lot of fear about China. All of those elements come into play, and I just want people to come and see the movie and ask themselves if sometimes when we don’t like something, is it really that thing that we don’t like or is it an idea that we don’t like? It could be something like a stereotypical image that you don’t like, but if you get to know people or things a little bit more, you will hopefully get to understand them.

I think the movie is all about seeing beyond what the stereotypes are, regardless of whether it’s Hong Kong and China, East and West, etc. It’s all about seeing the universal. A lot the times we judge people too much, and now we are living in an era that is very xenophobic, even more so than before, which is shocking to think. We have been so xenophobic all these years and now we have even topped that, like with Britain leaving Europe and everyone being so scared of Muslims and Trump going around talking about building a wall, and people are actually supporting that. I wonder what’s going on with this world. We are living in a world that is so xenophobic and that’s not the way to go.

Promotional poster. Photo credit: Front Cover

Promotional poster. Photo credit: Front Cover

GD: We haven’t been able to see the film out here in Taipei yet, but it is opening at this year’s Taipei International Queer Film Festival. What are your hopes for the film here?

RY: Taiwan is similar to Hong Kong in many ways; it has been very influenced by American culture. I think Taiwan could see a lot of that East meets West in the film, as I think that Taiwanese guys are quite Americanized. I have many Taiwanese friends and Chinese friends as well, and they are good friends with each other, some are even dating each other. It’s only really when it comes to people in the higher positions that there start to be issues. These things are very important to people who end up working in the government, but maybe not so important to a lot of the people who just want to have more shared experiences.

We are hoping to get a theatrical release in Taipei. It really does depend on the audience’s reaction at the festival. Again, in Hong Kong after the festival last year the reaction was so good that they decided to release it in the theaters. I really feel like a movie needs to be shared. Now we are so used to watching everything on a small screen, but it just can’t replace the feeling of everyone in the same room feeling the same thing as they watch these characters go through their stories on screen. I hope in Taiwan that same thing will happen when audiences see this story.