by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

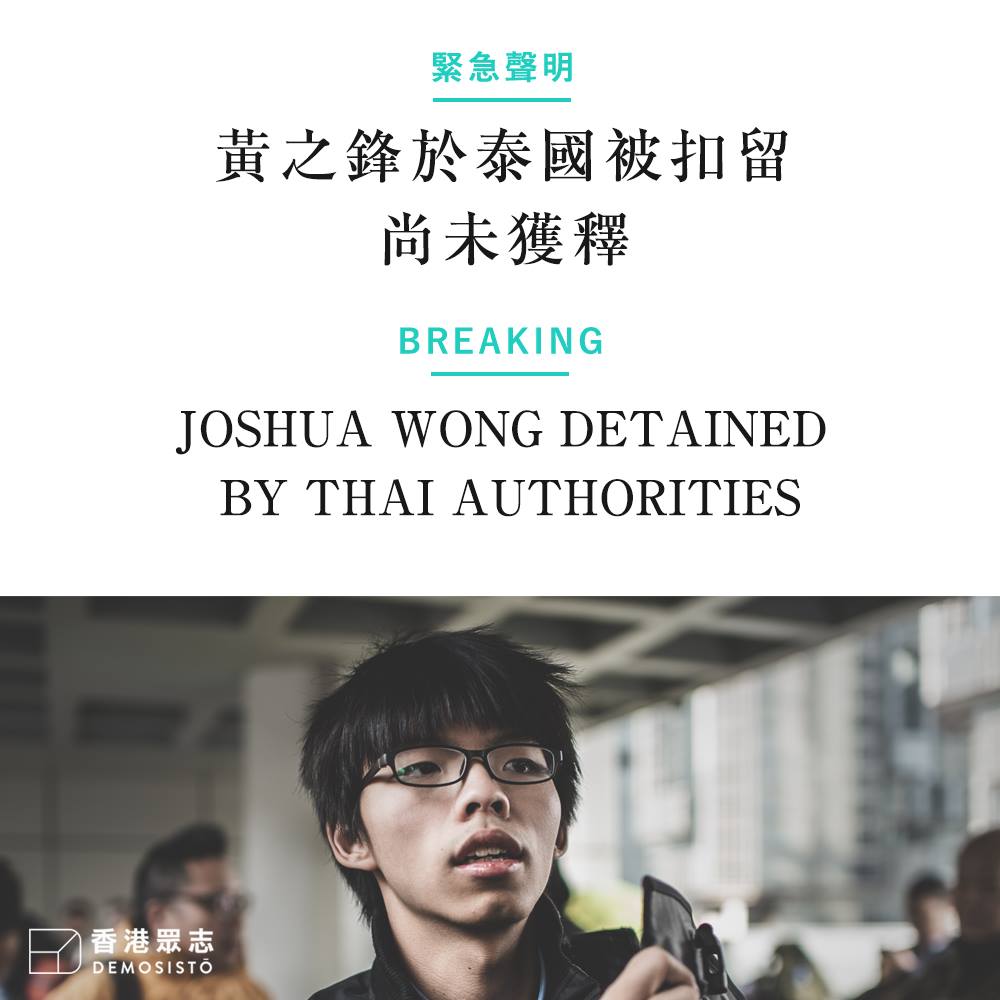

Photo Credit: Demosistō

THE DETENTION of Joshua Wong at an airport in Thailand for over twelve hours on Wednesday has provoked shock and anger. The request for Wong’s deportation came from Chinese authorities, something Thailand has waffled between admitting and denying.

Wong was detained at Suvarnabhumi Airport, having originally been slated to give a talk at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok about his experiences as a pro-democracy activist. The talk was part of a series of events supposed to commemorate the 1976 Thammasat University massacre, when Thai security forces and far-right paramilitary forces massacred student activists demonstrating against military dictatorship. Notably, Thailand is currently ruled by a military junta which took power in 2014, suggesting that in addition to wishing to please China, Thai authorities may have their own interests in cracking down on commemorations of the massacre.

After being detained by Thai authorities, Wong eventually boarded a flight back to Hong Kong. During the twelve hours he was detained Wong was not allowed to communicate with anyone, including his parents, lawyers, or members of the political party he founded, Demosistō. Wong’s detention led Demosistō to issue a public statement once they were notified of the situation by Netiwit Chotipatpaisal, who was originally supposed to meet Wong at the airport. Chotipatpaisal is himself a noted student activist in Thailand as the founder of a student group demonstrating against state-mandated patriotic education, a similar background to Wong.

Flyer calling attention to Wong’s disappearance put out by Demosistō. Photo credit: Demosistō

Flyer calling attention to Wong’s disappearance put out by Demosistō. Photo credit: Demosistō

Demosistō also organized a demonstration outside the Thai embassy on Tuesday afternoon, though by that time Wong had already boarded a flight back to Hong Kong, arriving later that afternoon. Other participants in the demonstration include the League of Social Democrats, People Power, Socialist Action, Defense of HK Freedom, and legislators Eddie Chu and Lau Siu Lai. It is to be questioned whether Wong’s eventually being released was a product of public pressure after Demosistō put the word out about Wong’s detention. It is possible that there were originally other plans for Wong.

Indeed, Wong has stated that he feared being “disappeared” and becoming another Gui Minhai. Gui was one of the five booksellers who sold books critical of Chinese leaders who kidnapped by Chinese security forces in 2015. In particular, Gui was kidnapped by Chinese security forces while in Thailand, something which was unlikely to have happened without the cooperation of Thai authorities. Wong’s detention at the behest of Thai authorities seems to confirm this interpretation of Gui’s kidnapping, signaling the willing cooperation of the Thai government with the Chinese government when it comes to handling dissidents against China visiting Thailand.

Wong was similarly refused entry to neighboring Malaysia in 2015, though he was not detained the way he was in Thailand, and Wong’s being denied entrance to Malaysia may have been because Malaysian authorities feared damaging ties with China—not because China had requested it. Though like the Chinese party-state, the Thai military government is also not exactly the most progressive government where human rights are concerned, Wong’s detention occurred in spite of the fact that such a detention would have inevitably provoked a great deal of international outrage. This suggests that the Thai government was willing to risk international outrage in order to please China. As such, it seems that Wong’s detention is yet another sign of China’s growing influence over Thailand and other countries in the Asia Pacific. There have been criticisms from within Thailand as well, however.

Photo of Wong taken after his release. Photo credit: Joshua Wong

Photo of Wong taken after his release. Photo credit: Joshua Wong

Yet with growing influence by China over countries in the Asia-Pacific, this raises the specter of Chinese extraterritorial detentions, with China beginning to apply its laws to those it considers it citizens when they are abroad—even if they are not strictly Chinese citizens. Gui Minhai, for example, was a Swedish and not Chinese citizen at the time of his arrest, Chinese law mandating that Chinese citizens must forfeit their Chinese citizenship in order to gain foreign citizenship. Residents of Hong Kong oftentimes are Chinese citizens, but in recent times, there have also been reports of China treating Canadian citizens of Chinese descent as though they were Chinese citizens.

Perhaps Wong’s detention indicates there will increasingly brazen actions by China regarding individuals it considers its citizens. For example, in Taiwan, it has been suggested that China could begin to pressure countries to treat Taiwanese abroad as though they were Chinese citizens. Individuals advocating “separatism”, such as Taiwanese independence activists, can be persecuted for treason under Chinese law. What if China begins to prosecute Taiwanese independence advocates traveling outside of Taiwan for treason and deports them to China, with the cooperation of the countries they are traveling in?

Such scenarios are hypothetical. Countries as Thailand which already share with China a record of poor human rights and are ruled by authoritarian governments are probably more likely to cooperate with China regarding extraterritorial detentions. This would be because such regimes have less to lose from international condemnation, already being known for a poor human rights record. But it remains to be seen whether Joshua Wong’s detention in Thailand marks the beginning of something new.