Hou’s Flight From Politics Into Aesthetics

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English /// 中文

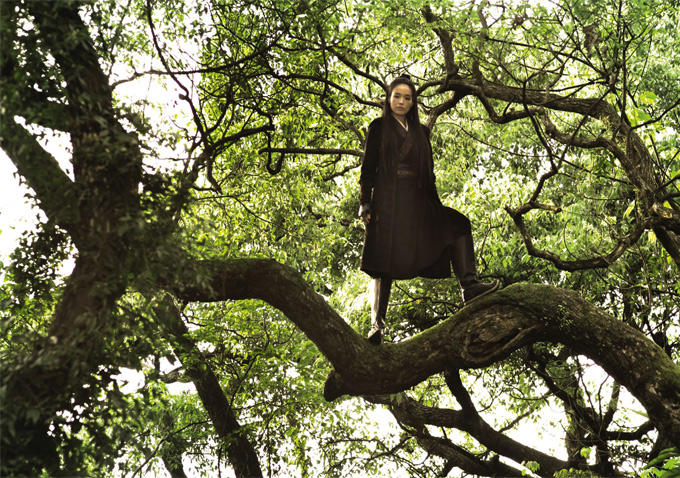

Photo Credit: The Assassin

The Aspiration of “Chinese” Filmmaking Towards Art Film

HOU HSIAO-HSIEN’S The Assassin has been hailed in predictably familiar terms to those who have been attentive to the reception of Sinophone film for past years. Certainly, the film is beautifully shot. And this would be what reviews have largely praised; that is, the beautiful and “lavish” nature of the film’s visuals.

If critics have pointed to how The Assassin is decidedly a very slow film, therein lay the film’s aspiration towards the art film. The Assassin is not an easy film to enter into. That may be the point. The film is almost designed to be viewed as an art film. But if the film is also hailed as a martial arts film in the “Chinese” mold, we might note how the film partakes of the “low culture” of the “Chinese” martial arts film—perhaps all the better to find commercial success.

For some time now has China desired to win the status of “high culture” in order to mark that with its political and economic rise, so, too, has China been able to match the standards of western artistic production. So would it be that a Chinese winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature was long desired. It was disappointing to China that Chinese novelist Gao Xingjian, who had led a life in voluntary exile after the Tiananmen Square Massacre and naturalized to French citizenship, would in fact become the first “Chinese” to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2000. As a result, China would be more unequivocal in celebrating Mo Yan’s winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012.

Hou at the Cannes Film Festival. Photo credit: Yahoo

Hou at the Cannes Film Festival. Photo credit: Yahoo

It would be such that in the domain of film, the “Fifth Generation Filmmakers,” including Zhang Yimou (who adapted Mo Yan’s Red Sorghum to film), Chen Kaige, and Tian Zhuangzhuang, have produced film almost deliberately aimed at garnering awards on the film festival circuit—as “art films.” The work of Zhang, Chen, and Tian alike for the most part share the characteristics of being slow-paced and aesthetically opulent. Through the awards garnered on the film festival circuit by the fifth-generation filmmakers would China prove that its film belongs not solely to the realm of “low culture,” as in the martial arts film which are quite often thought of as traditional Chinese filmmaking. The reception of “fifth-generation filmmakers” would, too, be along the lines of western auteur theory, with the notion that a director is the “author” of a film. We can generally see an analogous phenomenon with the reception of The Assassin and its being fêted on the international film festival circuit, winning no less than the Best Director Award for Hou at the Cannes Film Festival, and winning the awards for Best Director and Best Feature Film at the Golden Horse Awards.

But we might question, is The Assassin really a Chinese film? The film was Taiwan’s submission to the Academy Awards for the category of Best Foreign Film, not China’s. Although most definitely set in and filmed in China, the film’s director, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, is Taiwanese. However, any western viewers probably will perceive the film as quintessentially Chinese in nature. And it would be that the majority of the film’s funding seems to have come from Chinese sources. If critics to date have been too willing to take the film at face value, as only art for it’s own sake, we might point to these geopolitical, socioeconomic, and ideological elements undergirding the film.

A “Chinese” Film or “Taiwanese” Film?: “Sinophone” Film Taken Only As “Chinese” Film

FOR ALL THE perceptions about Chinese film, is it really that such film is actually Sinophone film and not actually Chinese, per se? To begin with, much of what is viewed as “Chinese” film actually falls under questionable bounds. If directors like Hou or Wong Kar-Wai are hailed by western audiences as “Chinese” filmmakers, as hailing from Taiwan and Hong Kong respectively, we might question how much they are truly Chinese when they are from territories which have been cut off from mainland China for much of or all of the 20th century.

Both filmmakers have with their international success, ventured into film that partakes what is thought of as quintessentially Chinese filmmaking—the wuxia martial arts film. Wong Kar-Wai would, for example, make the wuxia epic Ashes of Time and more recent effort The Grandmaster. The Assassin is Hou’s similar foray. But Hou and Wong have thus ventured from Taiwanese and Hong Kong filmmaking into the terrain of what is thought of as traditionally Chinese film, with their art film spins on the Chinese martial arts film.

This they share with their mainland Chinese counterparts. With success, Zhang Yimou of the “Fifth Generation” would, too, venture into creating art film spins on the Chinese martial arts film with Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004). It is ironic that the next step of those Chinese art film directors who would have apparently proved that Chinese filmmaking is more than just martial arts film, but art film, would next venture into creating film aimed at making film which partakes of the Chinese martial arts film in order to draw international attention, yet nonetheless also aspires to the heady artistic merit of the art film. Zhang’s Hero is in fact a strikingly similar film with not only similar Fifth-Generation aesthetics, but a similar plot and similar political vision undergirding it.

English language film poster for The Assassin

English language film poster for The Assassin

Actually, we might note that the supposedly “Chinese” martial arts film was quite often actually produced in Hong Kong, for example, which was a British possession for most of the 20th century and not part of the territory of the PRC. Hence “Sinophone” may be a better rubric in which to evaluate much of the film which is filmed in a Chinese dialect, keeping in mind that even Mandarin is one of many Chinese dialects, merely the hegemonic dialect and the lingua franca of the PRC.

And if critics of the film have largely simply taken the film as is, can we point to to the significance of the film’s ideological underpinnings? It is interesting to note that Hou Hsiao-Hsien first came to international attention as a quintessentially “Taiwanese” film director, as the director of the first depiction of Taiwan’s White Terror in City of Sadness. In this way, ironically enough, Hou has been thought of as a “quintessentially Taiwanese” director in the international sphere. But we might reconsider after The Assassin.

Indeed, in recent years, with Taiwanese film production being overshadowed by Chinese film production by virtue of the latter’s vast resources compared to the former, Taiwanese film has increasingly become funded by Chinese money. Attendantly, as influenced by the influx of Chinese capital, Taiwanese film have drifted towards plots concerning the question of unification, more often ruling in favor of unification than not. The Assassin is no exception. If personal experience is any measure, it would seem to be that in the weeks prior to the film’s release, there was more advertising for the film in Beijing than in Taipei.

From Resisting the KMT to Becoming a Voice of the Pro-Unification Left

HOU HIMSELF CAME to be thought of as “quintessentially Taiwanese” within international evaluations of Sinophone film because of City of Sadness being the first film to criticize the KMT on the basis of the White Terror. But, actually, Hou’s political reviews are actually more reflective of his affiliation to the pro-unification Left, which was persecuted under the KMT, and participated in the dangwai movement to form a second party outside of the KMT but later split from pro-independence forces. Given that the dangwai movement was largely a united front whose sole basis of consensus was opposition to the KMT, with the question of independence and unification being sidelined on the basis of shared opposition to the KMT, it would be that after the rise of Taiwanese identity after democratization that the pro-unification Left and pro-independence Left would split.

Particularly divisive was DPP president Chen Shui-Bian’s emphasis on benshengren Taiwanese nationalism during his administration. Benshengren are, of course, “native Taiwanese” descended from earlier Han settlers in Taiwan previous to 1949 and constitute some 86% of the population. Hou, himself a waishengren, descended of the 10% of the Taiwanese population which came over from the mainland after 1945, would be a critic of Chen’s benshengren nationalism.

There is very much a point to critiques of the benshengren ethno-nationalism which were leveraged on during the Chen Shui-Bian era as a way of consolidating Taiwanese identity. But given that it is the waishengren composed a socially and economically privileged ruling class during the decades of KMT rule, Hou would find himself complaining about waishengren being disprivileged and deprived of the opportunities with the rise of benshengren to positions of power during the Chen era. Hou would complain about those with different ethnic identifications being shut out of funding where filmmaking is concerned. Yet even if it is true that ethno-nationalism during the Chen era led to the persecution of waishengren, Hou sounds somewhat like white people in the United States whining about loss of privilege being displaced by blacks after the Civil Rights Movement.

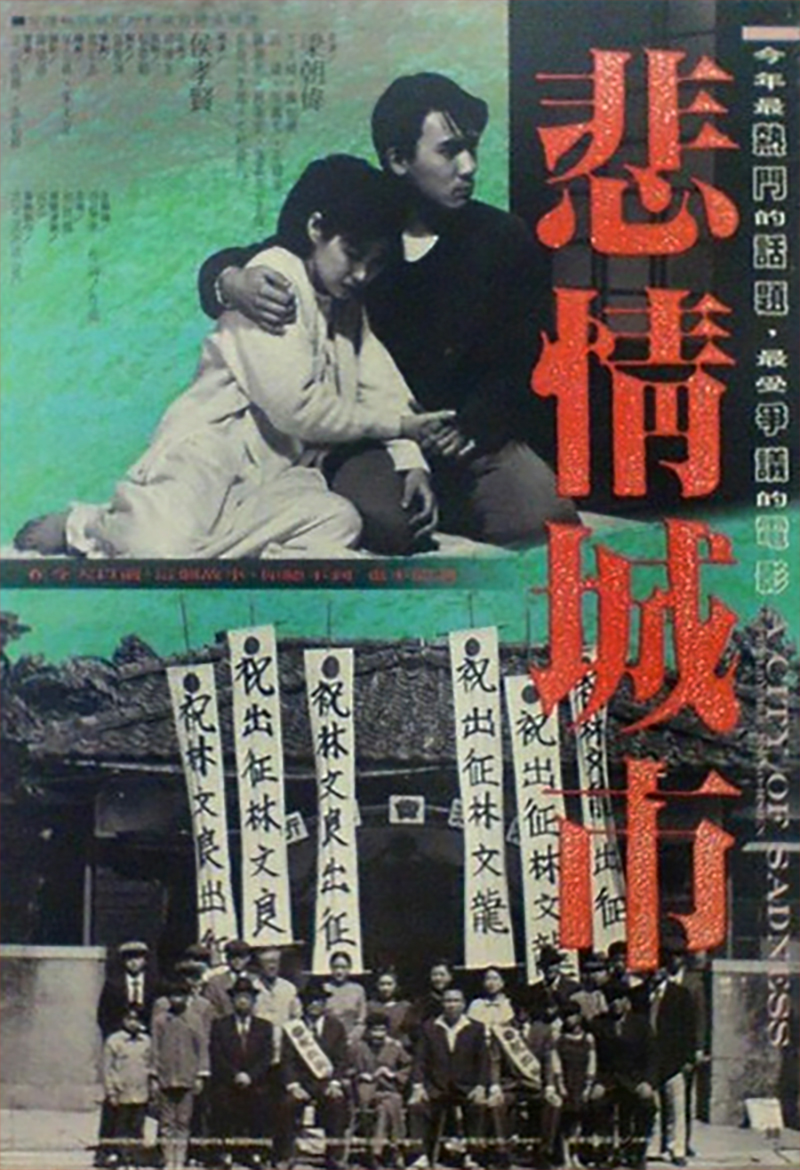

Film poster for City of Sadness

Film poster for City of Sadness

In this light, Hou would in this way double back on where he had been perceived as “quintessentially Taiwanese” by international observers, or even his film seen as marking the beginnings of incipient Taiwanese identity. Hou would claim that his concern with the 228 incident or the Japanese colonial period was not to affirm the 228 incident or Japanese colonial period against the KMT’s state-mandated Han-centric version of history, but rather that Hou was merely reflecting on the experience of his generation. Hou has also downplayed the differences between waishengren and benshengren, claiming that given the shared ability of the two sub-ethnicities to communicate in Mandarin and shared ethnic make-up, differences between the two were largely fictitious and only being leveraged on for the sake of identity politics.

And, unfortunately, where Hou had become representative of Taiwan in the international sphere, Hou’s statements along these lines would be taken up as representative of the Taiwanese Left! Given the international world is largely unaware of Taiwan’s complex ethnic and sub-ethnic politics, Hou’s statements were at times taken to be reflective of an unbiased viewpoint. Hou’s most damning statements in this vein may come from an interview in the New Left Review, the “flagship journal of the Anglophone Left”, which apparently saw Hou’s statements as sufficiently representative of the Taiwanese Left that it would take his words at face value.

Indeed, Anglophone scholarship about Taiwanese film, lagging as it is behind what is actually discussed within Taiwanese academia and intellectual circles, remains largely convinced that Hou is a quintessentially Taiwanese filmmaker. Never mind that Hou remains in favor of unification and is probably convinced of its inevitability—a view which may be accentuated on the basis of his working in the film industry—in which the influx of Chinese capital in past years may give rise to the view that, in light of economic integration, unification is more inevitable than ever.

The Aesthetics of the Assassin

IF INDUBITABLY a beautiful film, as has been noted by many Chinese and Taiwanese commentators alike, beneath the fine aesthetic gloss of the film is the question of unification/independence politics about Taiwan. The Assassin is loosely based on a classical Chinese tale originating from the Tang dynasty short story collection, the Legend of Pei Qing. Although not actually a very famous tale of Tang short stories (傳奇), it is this backdrop which provides the imaginary landscape for Hou’s fable.

And this is a landscape altogether imaginary. Although Hou himself insists that the film aims to be authentic to its Tang dynasty backdrop, the most visible feature of the film’s constructedness in spite of its aspiration to historical accuracy may be its dialogue. The film’s dialogue takes place in a strange combination of classical and contemporary Chinese, as well as mainland Chinese and Taiwanese Mandarin and many actors have strong Taiwanese accents.

There are times at which characters affect speech in classical Chinese as spoken in Mandarin, usually in more formal occasions, and then switch to speech more resembling contemporary Mandarin. Indeed, “classical Chinese”, which might be better translated as “literary Chinese” (文言), was not truly a spoken vernacular, but used for literary writing only. It took years of training to be able to read and write the highly elevated writing of classical Chinese.

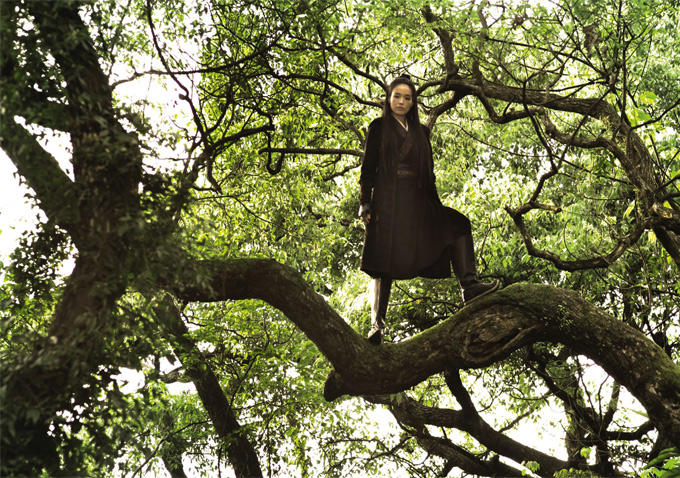

Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin

And though in the film, classical Chinese is spoken in Mandarin, that is, read with Mandarin pronunciations, Mandarin is a modern tongue based on northern Chinese dialects. Those alive during the Tang dynasty would not have spoken in Mandarin but rather “Middle Chinese”—a language lost to us which is approximated only through linguistic reconstruction and which forms the basis of many of today’s dialects, including Cantonese and Hokkien. This seems indicative of that Hou yearns for a lost historical totality—except what is lost can never be fully recovered. When classical Chinese as read with Mandarin pronunciations is used in the film, however, even then is grammar and word usage sometimes off key.

More confusing yet are several scenes when a character speaks in the classical Chinese recitational cadence (抑揚頓挫) and another character responds to him in classical Chinese are spoken in contemporary Mandarin. The effect is almost like a Shakespearean actor reciting his lines with authentic Elizabethan pronunciation and another actor reading Shakespearean lines with contemporary English pronunciation in response—although to be sure, recitational Chinese was never a real way of speaking and only used in recitational settings, as in reciting poetry.

Such disjunctures are striking. That The Assassin’s strange use of pseudo-classical Chinese is haphazard and inconsistent would point to the film being Hou’s mythicized image of Chinese history, rather than anything actually resembling historical accuracy, regardless of any of Hou’s claims to the contrary. Along such lines, probably it is that the setting of the Tang dynasty is chosen because of the view of the Tang dynasty as a quintessentially Chinese dynasty, representing one of the high points of Chinese civilization. But these discrepancies about language points towards the constructed nature of the history within the film. What we would see is more something like the simulacra of history; the acting of what seems to be authentic at first glance, but which more closely corresponds to history in the popular imagination than actual historical accuracy.

Moreover, with the Taiwanese director, Taiwanese scriptwriter, and the use of Taiwanese actors within the film, the film’s dialogue thus introduces a large degree of Taiwanese Mandarin. In fact, dialogue is so far removed from Chinese Mandarin that Chinese audiences sometimes had difficulty understanding it. Indeed, whatever language programs in Taiwan seeking to attract students away from China claim, Chinese and Taiwanese Mandarin can differ quite substantially at times because of their linguistic separation of some seventy years and the generation which grew up during the Japanese colonial period speaking Japanese, not only in regards to vocabulary but also in regards to grammar.

This is quite ironic where the script is concerned, given that the film’s script was written by Hou’s close collaborator Chu Tian-wen. Though certainly one of the greats of contemporary Taiwanese literature, Chu is well-known for her pro-unification stance regarding Taiwan and China, being a Hakka, waishengren descendent of members of the KMT military that came over the mainland, much like Hou himself. Certainly, sometimes wonders if the vision of “China” constructed by such individuals as Hou or Chu is not in fact imaginary, a projection or longed for, aestheticized utopia onto reality. Yet, as the unconscious traces of language goes to show, there is no avoiding the fact that Hou and Chu are not mainland Chinese, regardless of their self-claimed political or cultural identification.

Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin

And it would seem that the construction of an aestheticized, imaginary landscape is quite crucial for the figuration of China in Hou’s imagination. If the film’s landscapes are “lavish,” we might point to the figuration of China as a space of vast natural beauty in Hou’s imagination. It may be that the countryside areas of Hubei and inner Mongolia, where The Assassin seems to have been largely filmed, are in fact so beautiful. But we might point also towards the crucial role of the “landscape” in the nationalist imagination, whether in European cases, the Chinese example, or the Japanese one, that the landscape looms large in the nationalist imaginary of the nation-state as aestheticizing the territory of a nation as an object of romantic idealization. So the visual beauty of The Assassin—as is also the case with Chinese Fifth-Generation Film— ultimately may have nationalist underpinnings, reflective of a broader sense of aesthetic projection onto China.

An Allegorical Tale of Taiwan and China?

BUT IT IS in the plot of The Assassin in which individuals have largely pointed to its political content regarding Taiwan and China. The Assassin concerns the breakaway province of Weibo. The eponymous assassin, Yingniang, is dispatched to assassinate the lord of Weibo on behalf of the emperor because the way of the emperor is synonymous with the rule of heaven. It is mentioned that Weibo has the popular support of the people, hence why it was able to break away from the central authority of the Tang court without collapsing.

Shades of Taiwan, anyone? It is, of course, that the PRC views Taiwan as a renegade, breakaway province, whose ability to prop itself up as an independent nation-state has been on the basis of the popular support of the Taiwanese people.

Although probably a confusing element for western viewers, who are not familiar with the literary and historical tropes drawn on by the film or adopted from the source text, Yingniang’s acting as an assassin is on the basis of her membership of an order of nun-assassins who carry out assassinations in the name of the emperor. Though probably western audiences will see this in line with martial arts films, this is a wuxia (武俠) trope, insofar as the genre of wuxia is the origin of many of the tropes we have come to know as part of Chinese martial arts film.

Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin

Yingniang is properly a wuxia protagonist, a xia “knight-errant” (俠), who carries out the path of justice, righting wrongs through prodigious martial arts skills, and then disappears. Specifically, Yingniang is a female xia, or nuxia (女俠). Within the tradition of wuxia fiction, xia knight-errants were wanderers who prioritized the path of justice above all else, going against the rules of established authority. To provide a sense of comparison for those unfamiliar with wuxia fiction, we might compare xia knight-errants with the tradition of drifting gunslingers in spaghetti westerns as Sergio Leone’s “Man With No Name.” The “Man with No Name” is, of course, based on the eponymous character in Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, a figure that draws from Japanese transculturations originally derived from Chinese xia fiction.

It was always a tension within wuxia tales as to the relation of xia to established authority, in that Confucian discourse would have it as that righteous lay with governmental authority. However, xia values prioritized justice above rules and authorities ran contrary to Confucian morality. But in some stories, xia are depicted as operating in service of the emperor, or with Confucian scholar-officials themselves acting in xia-like roles. The character of Yingniang, an assassin in service of the emperor, would point to many of these tensions between xia values and Confucian values which prioritize loyalty to the emperor.

What is it then that Hou would seem to be point to through the character of Yingniang? Though herself a woman of Weibo and the former betrothed to the lord of Weibo, it is that Yingniang does not assassinate him in the end, and decides to flee with some of her relatives from Weibo. Is it that Yingniang chooses love in the end? Or that the values of xia ultimately triumph over Confucian loyalty to the emperor? More precisely, it would seem to be that Yingniang just does not make any concrete decision and instead chooses to flee. The fate of Yingniang and of Weibo would seem to suggest Hou’s own views on the fate of Taiwan where China is concerned—and his own role.

Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin

It is ironic to note that Hou’s nickname, as derived from the title of one of his films, is “The Puppetmaster.” Perhaps we should start calling him “The Assassin” now.

Actually, for those who are familiar with the history of the story upon which The Assassin is based, it is that Yingniang does not kill her former betrothed and disappears, never to be seen again. In the end, as corresponds to historical reality, Weibo becomes conquered by the central government, regardless of Yingniang’s actions. Maybe this is how Hou sees himself in regards to Taiwan and China.

If some have sought to absolve Hou’s film from political subtext, claiming that Hou was merely following the text upon which The Assassin is based and that in this way the film is merely art for art’s sake, this is hardly so. Hou could have chosen any number of stories with similar themes, but he chose The Assassin instead. If those who claim that Hou is an “artist” above all else, and in this way rises above worldly political concerns, we might also point out that the story upon which The Assassin is based is actually not very famous.

But it was this one which Hou chose, as corresponding most closely to his political ideals as he would be able to represent them in film. And for all Hou’s insistence on his fidelity to the source text, it is that the tale of The Assassin is not so well known that Hou would be limited in needing to conform to the audience’s expectations of what a proper adaptation of a famous story must entail in terms of plot. So could Hou, then, mold the text according to his political vision.

Conclusion: A Flight From Politics and Into Aesthetics; Attempting to Flee The Political Game By Not Playing

HOU IS ULTIMATELY a filmmaker of the pro-unification Left. In this way, Hou was a part of the resistance against the KMT’s authoritarian rule, as seen in City of Sadness’s incisive critique of the KMT—and Hou’s heroic role as the first filmmaker who dared to depict the White Terror on film, risking the possibility of actions by the KMT against him only two years after the end of martial law and one year before the outbreak of the Wild Lily movement.

But it is that Hou’s ultimate political identification with China has led him to have an ambivalent relation to Taiwan and rather reprehensible views about waishengren and benshengren identity. This was the split between the pro-unification and pro-independence Left which occurred after the end of authoritarian rule in Taiwan, when the two had previously existed in alliance on the basis of shared opposition to the KMT, particularly after the flaring up of Taiwanese identity and the questions of identity raised during the Chen Shui-Bian administration. We can see the reflection of this past history in The Assassin.

Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin

It would be mistaken to see Hou as a quintessentially Taiwanese filmmaker, as much Anglophone scholarship continues to do so. However, neither does it do to attempt to crucify Hou solely on the issue of his political identification with China.

Ultimately, it may be that caught between these opposing imperatives, caught between China and Taiwan, between the xia affinity for the oppressed which led him to attack the KMT in the past and Confucian morality which would mandate his allegiance to China, Hou only wishes to run away. And The Assassin may be Hou’s attempt to flee into an aesthetic wonderland as a way of avoiding confronting political reality. Hou’s The Assassin thus ends with the eponymous character fleeing into the aesthetically beautiful landscape which has been depicted throughout the film, symbolic of Hou’s flight into aesthetics to avoid politics.

But reality is not so easy to avoid. Hou no doubt is cognizant of the realities of economic and political power between Taiwan and China. With the production of The Assassin itself, Hou would have seem to have had China in mind as a major market for the film. And so, Hou himself has to own up to his role as an actor within the complex geopolitical and socioeconomic field between Taiwan and China. Moreover, by fleeing, Hou’s Assassin only avoids personal confrontation with the reality of that Weibo will eventually fall to the Tang—but this does not foreclose her from political responsibility either, in choosing to run from this state of affairs. So, too, with Hou.

Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin

There is no non-political aesthetic space into which Hou can flee. Merely by creating the film, which will of course be read purely as “Chinese” and not “Sinophone” or “Taiwanese”, Hou is already caught up within political entanglements between Taiwan and China. Hou’s attempt to evade the entrapment of the political game would be to not play. But it is that all art is political. For though he may try to claim otherwise, Hou has already been drawn into the game.

Hou at the Cannes Film Festival. Photo credit: Yahoo

Hou at the Cannes Film Festival. Photo credit: Yahoo English language film poster for The Assassin

English language film poster for The Assassin Film poster for City of Sadness

Film poster for City of Sadness Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin Still from The Assassin

Still from The Assassin