Lee Tzu-Tung

語言:

English /// 中文

Translator: Minmin

Photo Credit: Jessica Fu

0.

BACK IN MAY 2015, I attended the MFA show held at the School of Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), and saw Jessica Fu’s showcase. She painted on a transparent celluloid, and then used a profile projector to project the celluloid onto the wall; a dream-like imagery of the ink wash painting emerges, immersing the individual into this monochrome illusion when standing in front of the wall. She tries to convey her near-death experience during the Fukushima nuclear incident using such aesthetics. I felt that this art is special because Jessica, a citizen of Hong Kong, adopted ink wash aesthetics, but deviates from the strong notion of nationalism which often infused with original landscape (shanshui) paintings and literati paintings in order to illustrate her individual, sensual and fragile experience in Japan.

1. Shanshui Politics?

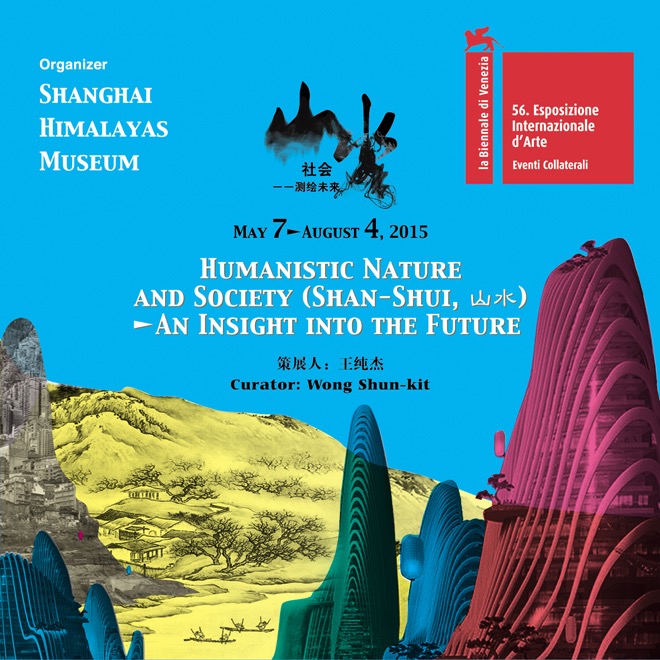

AN EXHIBITION themed “Shanshui politics”, was recently held at China’s Shanghai Himalayas Museum together with the La Biennale di Venezia, concerning itself with traditional Chinese landscape painting or shanshui (山水). The forum divided Chinese modern painting into three stages: The first stage featured artists such as Xie Shichen (謝世臣) and He Haixia (何海霞) attempting to depict ancient China’s shanshui scene. The second stage is featured artists such as, Wang Nanming (王南溟)、 Wang Jiuliang (王久良), and Ni Weihua (倪衛華), attempt to reveal China’s social issues through shanshui painting. The third stage discussed how Ma Yansong (馬岩松) and Chen Bochong (陳伯沖) use architecture to provide a solution to society’s problems through the shanshui context of human feelings and literary culture.

Photo credit: Randian

Photo credit: Randian

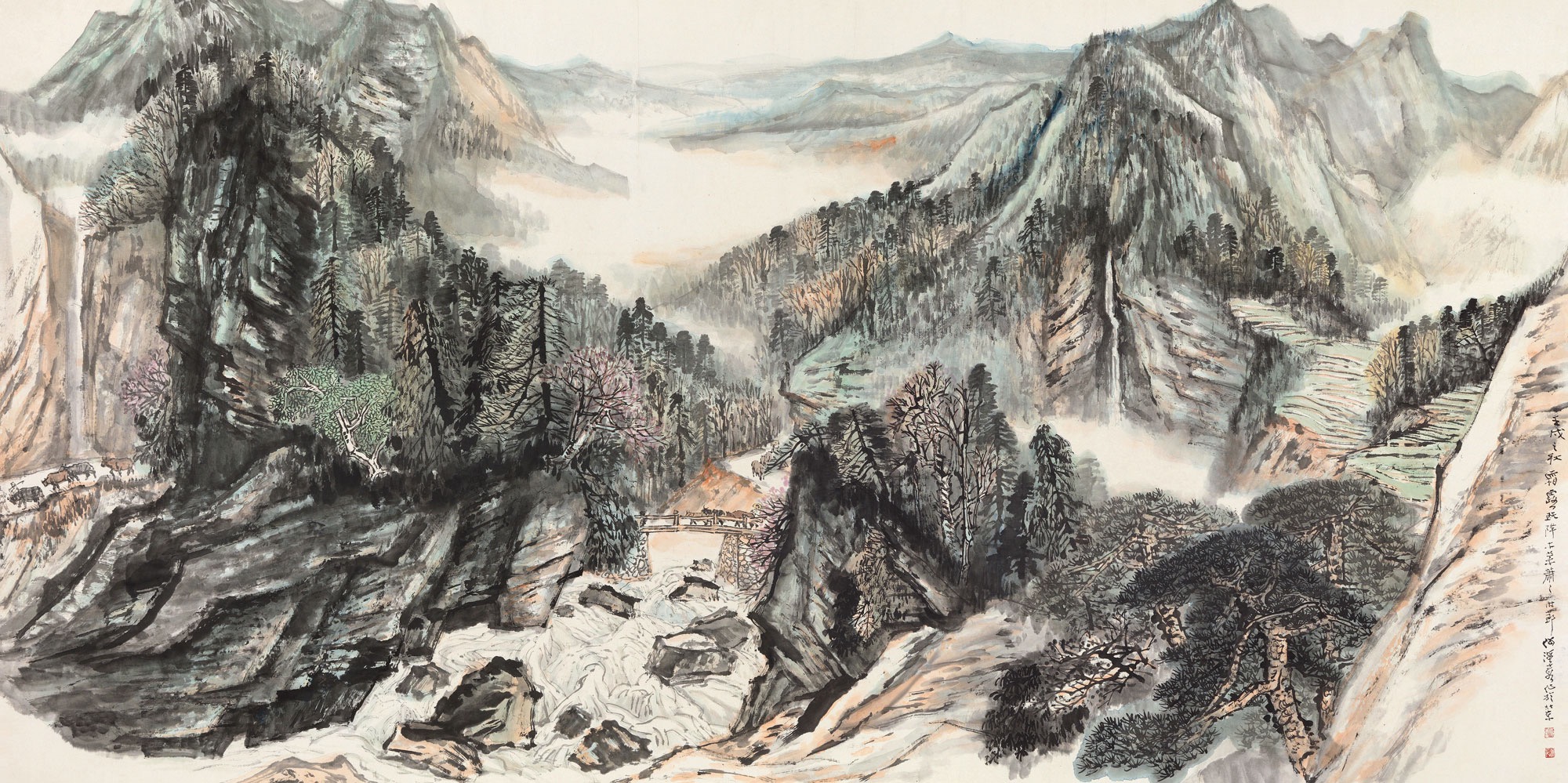

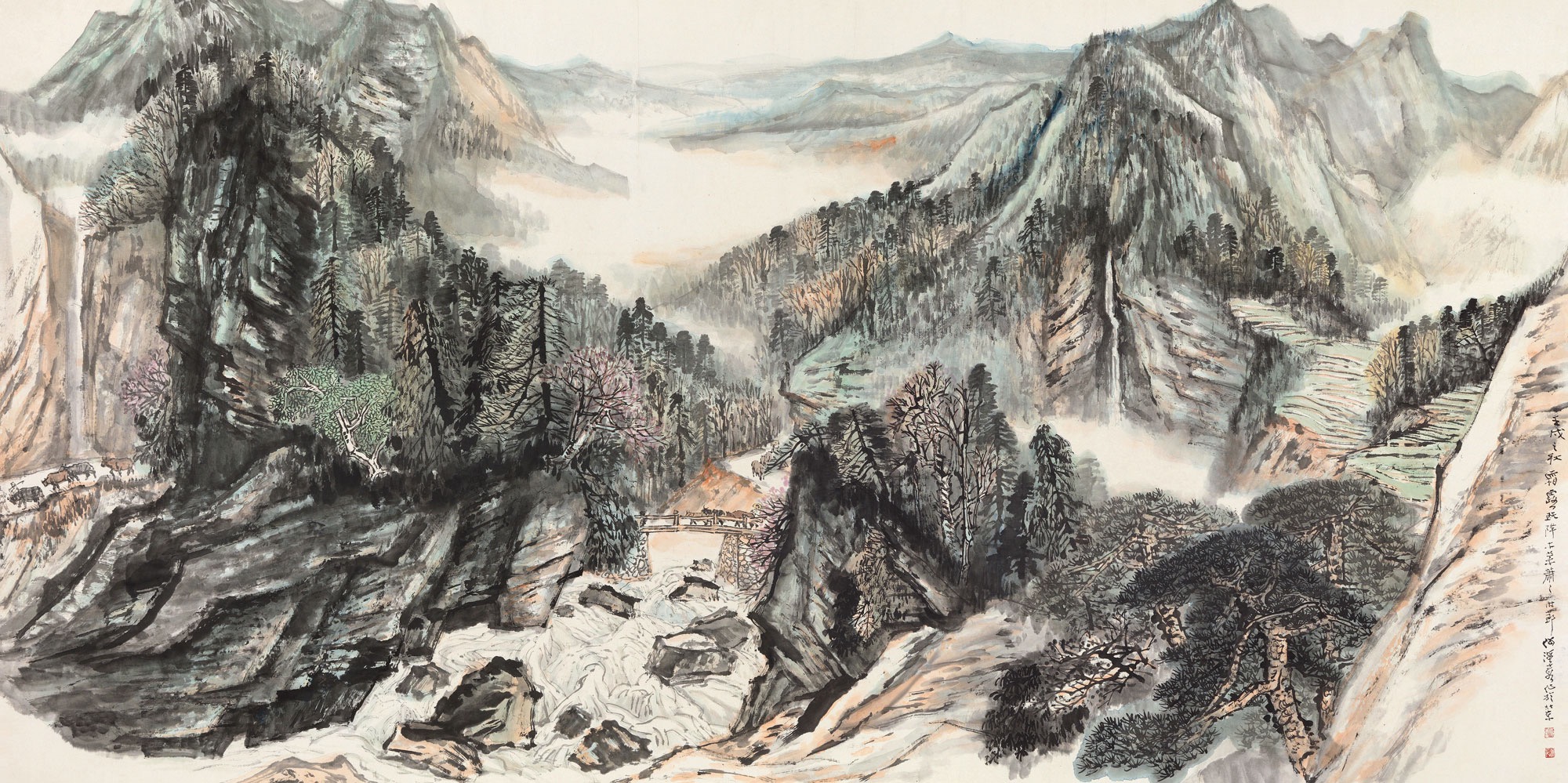

He Haixia (何海霞), Glen Torrents (幽谷奔流) [1982]

He Haixia (何海霞), Glen Torrents (幽谷奔流) [1982]

Wang Nanming (王南溟), “Rubbing Drought” (拓印乾旱) [2007]

Wang Nanming (王南溟), “Rubbing Drought” (拓印乾旱) [2007]

Why discuss the politics of Chinese landscape painting? China has been developing, experimenting, and creating shanshui paintings based on different themes and through different mediums. Traditionally, landscape painting not only represents the imperialistic Sinocentric culture that deeply rooted in literati’s mind. As these literati stand on the mountain top “looking” upon the great Chinese cultural and geographical territory in mist, the landscape painting now becomes the “map” of their imagined national glory. This represents not just the great “Chinese” imperialistic culture, but also a medium to remember the “Chinese” humiliation in a form of a political, cultural, and geographical context; which is a politically-correct motif for modern Chinese scholars and artists. Only through reading and understanding the changes of modern China landscape painting, can we then identify and understand the changing nationalistic sentiments of China after the end of the Qing era.

2. The Political Starting Point of Modern Chinese Landscape Painting

LANDSCAPE PAINTING occupied the forefront of Chinese art from the 10th century to the 18th century, until the late Qing Dynasty, when Western imperialistic forces came to China and forced out commercial trade through military power; it was not till then that the Qing Emperor decided to strengthen China through the Self-Strengthening Movement (自強運動), from 1865 to 1895. The movement mainly emphasized modern technology and institutionalization, policies such as buying battleship and guns from European countries, importing clock and traffic systems, as well as modifying the art school pedagogy by introducing sketch, color sciences, and techniques of chiaroscuro from the Renaissance period. [1]

However, due to a series of defeat and the total breakdown on First and Second Opium War, people soon lost their faith on this reconstruction that merely focused on modus and materiality, and decided to extend the improvement in larger scale. Scholars such as Chen Duxiu (陳獨秀), Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培) and Kang Youwei (康有為), who originally had classical education, began to lead a revolt against Confucianism through the New Culture Movement (新⽂文化運動) from the mid-1910s to 1920s, which aimed to eliminate all the bad habits inherited from “old China” and hence establish new ones.

In January 1915, Chen Duxiu published an article at New Youth (新青年) magazine asking “What is the ‘New Culture’ Movement?” and declared, “In order to know what New Culture is, we must know first what ‘Culture’ is: culture includes science, religion, ethics, art, literature and music; therefore, the New Culture Movement is to add and modify the disadvantage of the Old Culture on top of these areas.” Therefore, this atmosphere of cultural change swept and overturned the tradition of Chinese landscape painting.

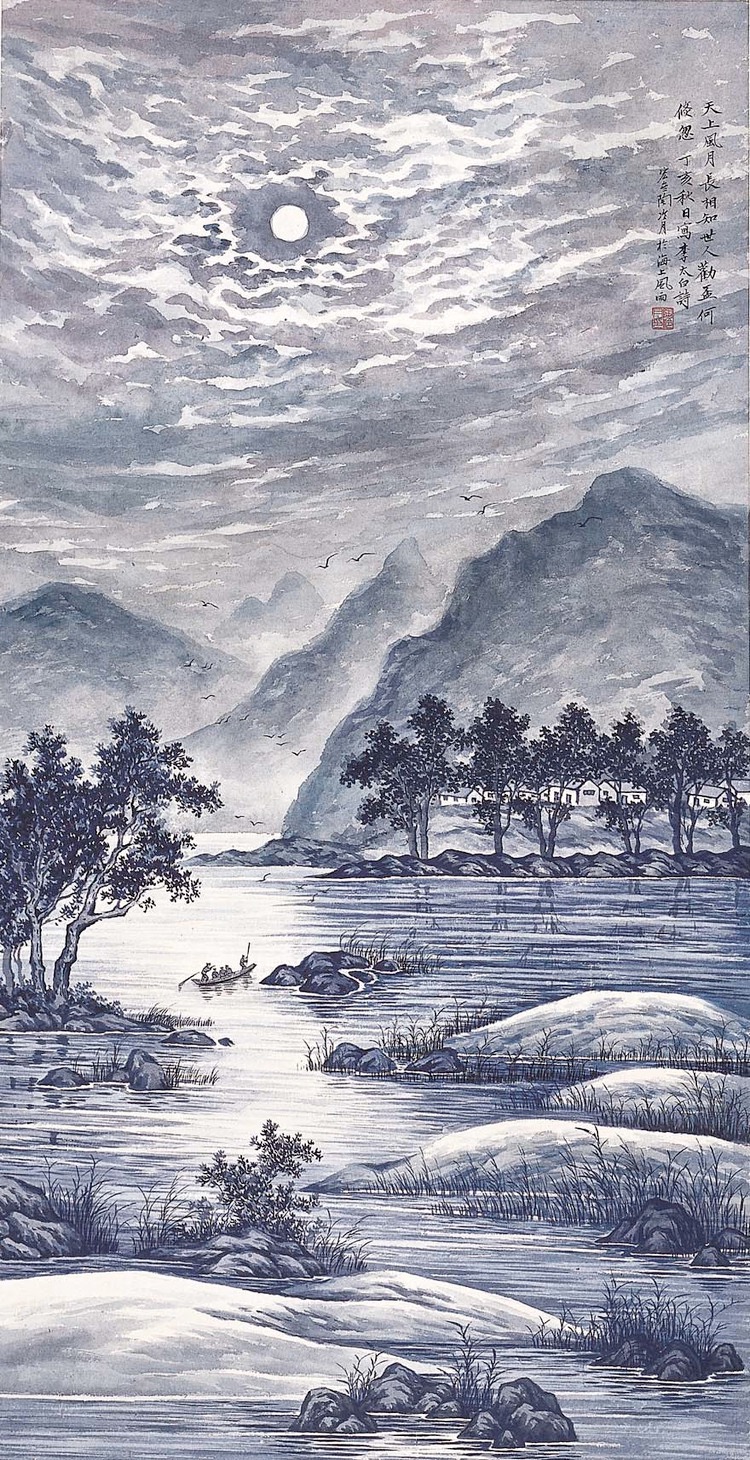

Tao Linyue [1927]

Tao Linyue [1927]

Kang Youwei [2], wrote in his preface to 1917 ”Catalogue of Paintings Collected in the Hall of Ten Thousand Trees” (萬⽊木草堂藏書⽬) that “Chinese painting in the recent era has declined to the utmost. Ancient Masters like the “Four Wangs and Two Shis” (四王二⽯) [3] are using brushes like dried twists, and having the taste like dry wax”. [4] He also stated that “only by importing the realism to Chinese painting can modify the obstacles in Traditional Painting. ” [5] In respond to Kang’s critics, the cultural minister [6] and the president of Beijing University, Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培), had also made the denouncement that “National painting draws people with no precision: fingers lack knuckles, legs are stiffed like wood, figures can’t turn their head…” In addition, as a former student who studied philosophy and civilization in Universität Leipzig, Cai was strongly infuenced by Immanuel Kant’s aesthetics, and held lots of concerts and cultural exhibitions, hoped these events would improve the aesthetic judgement of people along with the capacity of “thinking” and “will”. Moreover, art students such as Xiu Beihun (徐悲鴻), Zhao Wuzhi (趙無極) were encouraged by him to study Western art techniques in French art schools such as the Beaux-Arts de Paris.

Faced with pressure on traditional shanshui painting from the cultural leaders, artists started to debate amongst themselves: What characteristics of Chinese painting is considered beautiful, good, and worth preserving? What elements truly represent Chinese tradition, and needs to be perpetuated? What elements should be eliminated and conquered? What Western elements should we learn?

Some artist such as Hu Peihen (胡佩衡), Pen Tienshou (潘天壽) began to believe that every nation, every ethnic group should have their independent culture, instead of just adopting Western styles. In 1925, Pen stated, “We should keep distance on foreign cultures, and remind ourselves not to be fascinated by the other kind of style that will jeopardize the originality within each kind of art.”

However, these voices of opposition did not find acceptance. On the other hand, individuals who followed the same mind as Cai Yuanpei and Kang, surfaced and became a driving force behind the establishment of principles of modern Chinese landscape painting.

3. Tao-Lin Yue and Qi Bai-Shi’s; Their fate with that of Modern Chinese Painting

LET US NOW mention two artists, Tao Leng-yue (1895-1985) and Qi Baishi (1864-1957). In 1925, Cai Yuanpei fervently endorsed Tao as an artist, and endeavors to describe Tao’s style and artwork with the following: “The structure and the essences follows tradition; the picture and the essence, however, adopts a unique European feeling.” [7] Between the years 1930 to 1940, the Head of the Ministry of Culture then held Tao’s work of high-esteemed, leading to the value escalation of his artwork to fetch three times more than artists of similar background. [8] However, he was condemned of being a capitalist roader during the 1958 Cultural Revolution, eventually ending his artist career. For the next 20 years or so, he was responsible for painting the decorative flowers on thermos bottles until 1978 in Shanghai, until his reputation as a great artist was revived by a group of secondary students. Today in the arts, Tao, compared to other artists of the same era such as Fu Baoshi, Li Kojan, is less heard of.

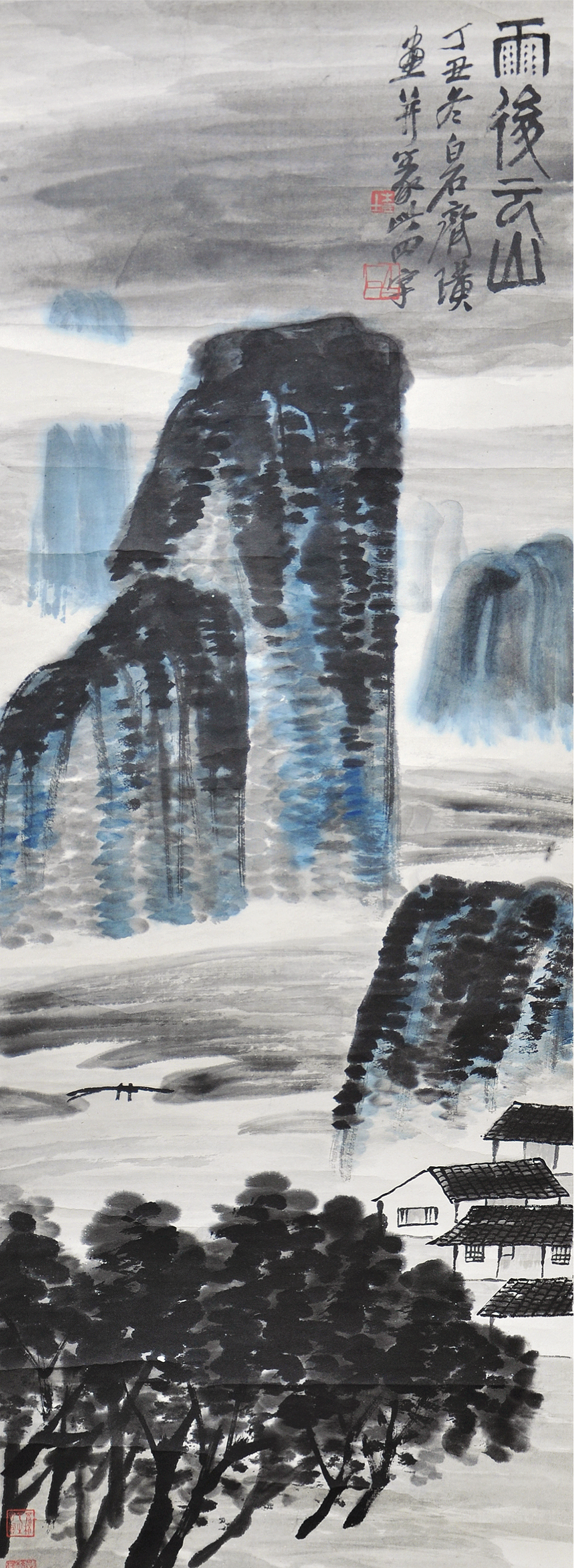

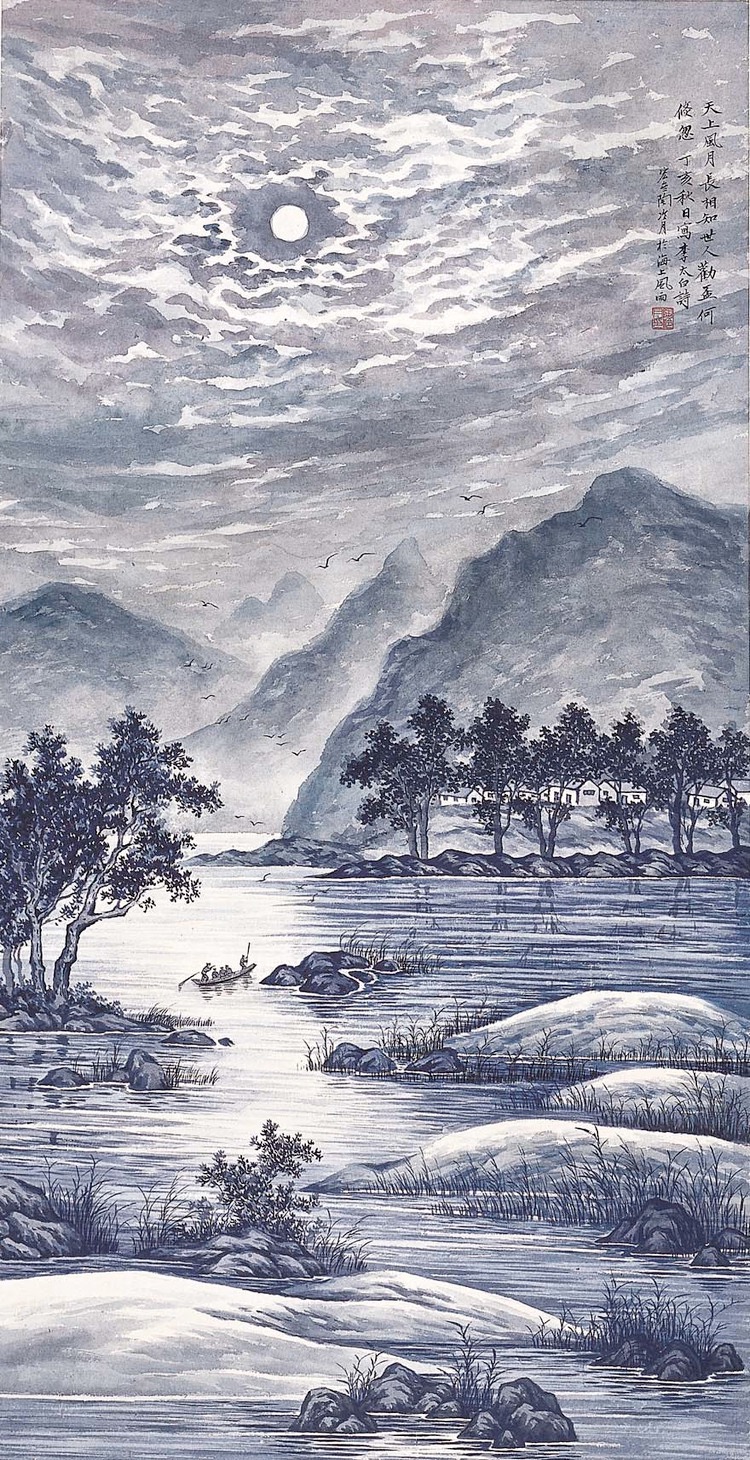

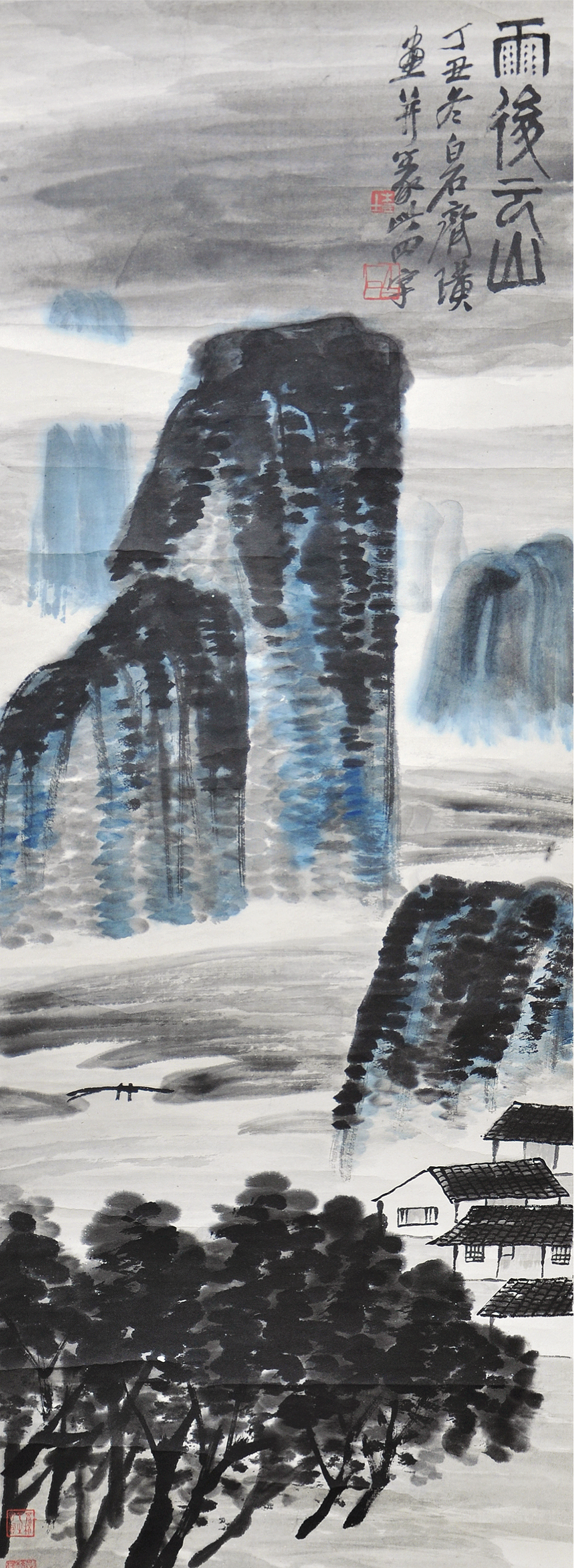

Qi Baishi, “Snow Mountain After Rain” (雨後雲山) [1928]

Qi Baishi, “Snow Mountain After Rain” (雨後雲山) [1928]

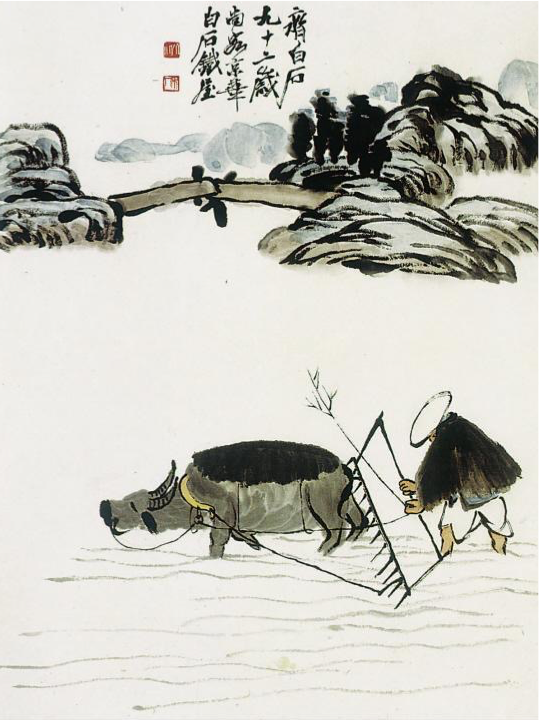

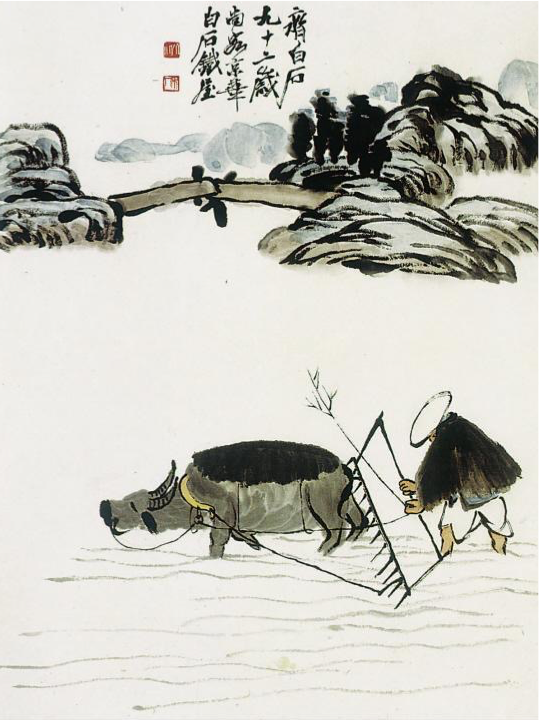

On the other hand, the unique and idiosyncratic Qi had the tendency of gifting his paintings to friends and family; as a result, he hardly profited from the artistic market. Qi particularly admired the works of Dong Qichang (董其昌), Shi Shitao (⽯石濤), and Badashanren (八⼤山人). As we can see, his work started to have a cubist interpretation of nature, using angular lines and geometric forms to render what could have been a flatter mountain.. Although, during the earlier part of his career, his artworks fetched little value in the market; yet he is now a reputable and highly-esteemed artist. Meanwhile, his disciple Li Kojan maintained a good relationship with Premier Zhou Enlai. In the later part of his life, he started incorporated peasant related themes into his art work, which due to his portrayal of a “peasantry aesthetic,” he was thus regarded by the China Communist Party as a noble and reputable artist.

Qi Baishi [1956]

Qi Baishi [1956]

The artist’s life and his work are much related to the political conflict at the time. Both Tao and Qi were following mainstream cultural policy, which encouraged artists to improve their works by incorporating western painting style. Tao used Western techniques of chiaroscuro while Qi used cubist touch that he learnt from France and Japan. However, appreciation of these two masters nowadays are in opposite to the 1930s. The rise of Communist Party and the following Cultural Revolution again made many artists fled out of China or choose to adopt their works with upcoming political ideology.

In addition, the unique transformation of these painting had also signaled an ideological depart from traditional landscapes. For example, Yi (意) and Chi (氣), that is to say, the atmosphere and energy eminent from the author, were considered as the most important qualities in traditional landscape painting. These unspeakable qualities, even though can be seen without further explanation, can only be fully-understand by elites who possess a large amount of cultural refinement. When the western philosophy of precision and the discourse patriotic nationalism in 20th centuries was forced to merge with traditional landscape painting, the Yi and Chi— the thousand years of communal intimacy shared between cultural elites —was also being destroyed.

4.

ONE OF THE questions that is often raised in the field of contemporary Chinese landscape painting is “Do these paintings testify to the survival or destruction of landscape painting? ” Since Qing empire collapsed in the 1910s, China has undergone wars and shifts in sovereignty between warlords and alien Western countries. “Memories” of defeat have become a national trauma, while “History” itself served as the real fiction to form national identification and give people expectations to wait on its revival.

Critic of Chinese nationalism Jerome Tseng (曾昭明) and left-wing Japanese scholar Kojin Karatani (柄谷行人) both observe: The birth of nation-states is a result of the refutation and separation of different imperial countries; because before the birth of the nation-state was the absolute monarchy, and establishes political authority which represses the principles of empire (For more information, review Jerome Tseng’s 歧路徘徊的中國夢:民族國家或天下帝國). As China was originally a world empire, the move to return to world empire is possible because the impulse to empire remains”.

As Michael Sullivan has noted, people’s attitudes to the landscape have changed fundamentally since 1949:

“The mountain and streams are no longer an object of contemplation, in which the viewer must lose himself and forget the ‘dusty’ world. They have become for most artist the visible symbol of resurgent China.”

Therefore, “art history” on the transformation of Chinese landscape painting, not only can be seen as a history of incorporation with Western style, but also should be regarded as the psychological molding process of building a culture’s subjectivity, in which artists contribute to the construction of national nostalgia and a literature of tragedy.

[1] Constitution of Pedagogy in Year Ren Yin. 壬寅學制 (1902),which also introduced the elementary, junior high and high school system to China.

[2] A restoration that last for only one hundred days due to political rivalry between the Queen and the Emperor.

[3] 王時敏、王鑒、王翬、王原祁、石濤、髡殘 (石道人)

[4] 枯筆數筆, 味同嚼蠟

[5 ] 輸入寫實主義, 改良中國畫的最大障礙

[6] Served in newly established Sun Yat-Sen’s government (the early Republic of China).

[7] 結構神韻, 悉守國粹;傳光透視,特採歐風