by Nathanael Cheng

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Zhao Sile

ZHAO SILE (趙思樂) begins and ends her book, Her Battles, with Ai Xiaoming (艾曉明), the aging literature professor-turned-documentary filmmaker and activist. In the first chapter, Ai Xiaoming is fifty-two years old, at the height of her activism, running from men in military uniform. These men are ostensibly government-sponsored thugs sent to prevent her from filming the events of the 2005 Taishicun incident in Guangzhou. At the end of the book, Ai Xiaoming is sixty-two, but she is still on the move, her beloved camera clutched in weathered hands. She and Zhao Sile are trudging in the mountains of Gansu in sub-zero temperatures to get footage for her 2017 documentary Jiabiangou Elegy (夾邊溝祭事), about the over two thousand accused “rightist” intellectuals sent to laogai prison camps in the Mao-era.

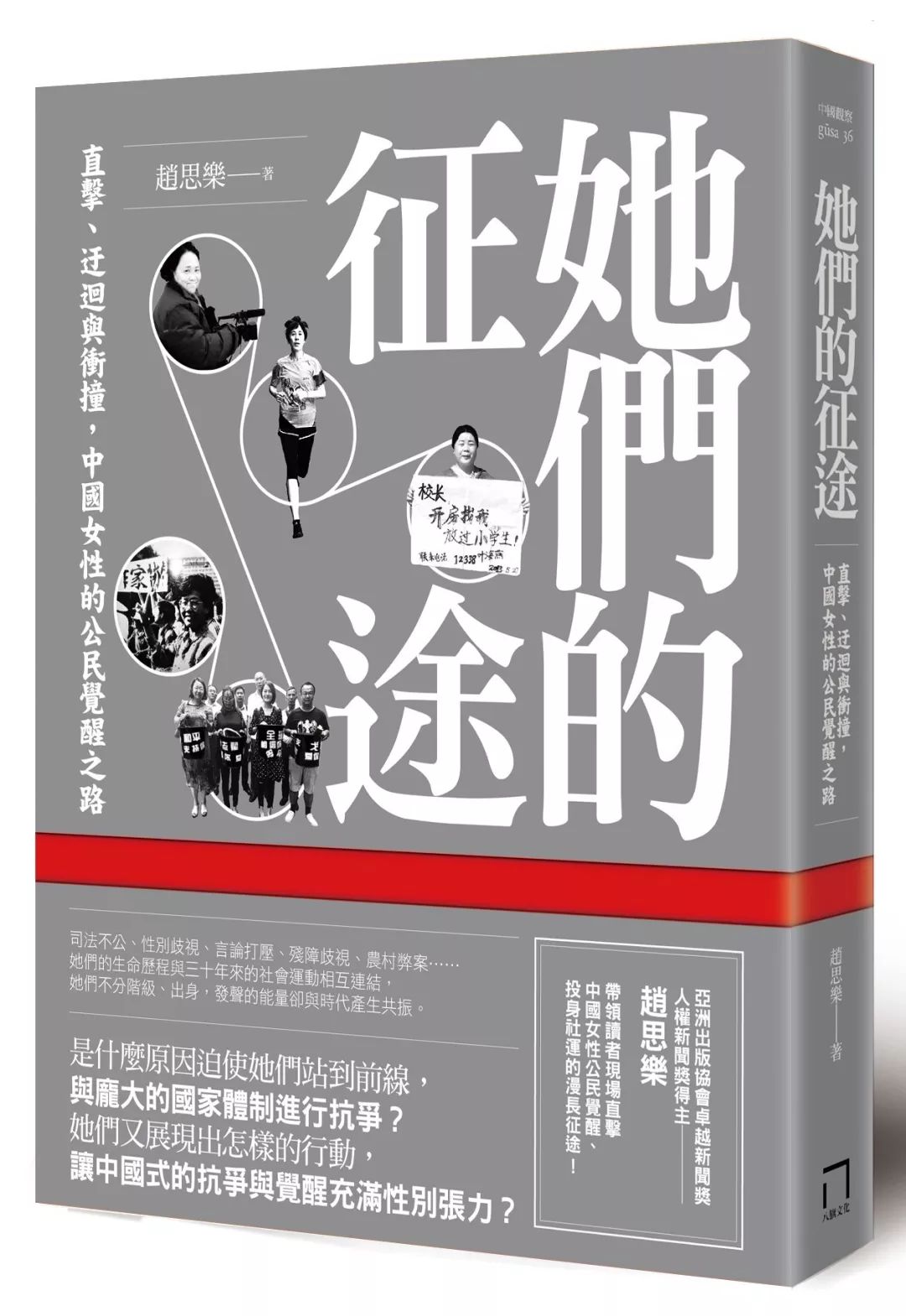

Not yet translated into English, Her Battles (她們的征途) tells the stories of female activists and dissidents in China and their activism, roughly spanning the early 2000s to 2016. Zhao deftly weaves the stories of these women together, touching on major events in China, such as the 2008 Olympics and the Jasmine Revolution that provide the backdrop to the events unfolding in their lives. The book’s subtitle, translated, reads “Attack, Detour, and Collision—The Path to the Civic Awakening of Chinese Women” (直擊、迂迴與衝撞,中國女性的公民覺醒之路).

Ai Xiaoming. Photo credit: 艾曉明/Facebook

Ai Xiaoming. Photo credit: 艾曉明/Facebook

Zhao tells me, however, that she didn’t choose the subtitle; her editor did. “I actually don’t like the word ‘awakening,’” she says. “It’s so stereotypical, as if people can suddenly wake up and open their eyes and realize the world is problematic, and they become a superman or superwoman. I think that’s a misleading metaphor.”

Averse to the superhero trope, Zhao does not stint in emphasizing the ordinariness of the titular characters. Ai Xiaoming is “moderately over-weight, as oft seen among the middle-aged,” with a “broad lower jaw, long and slender eyes, and thinly pursed lips.” Feminist activist Ye Haiyan (葉海燕), who went to Hainan to protest the kidnapping and rape of six elementary school girls, had her “hair combed messily back in a ponytail, with the sweat reflecting off her brow in the scorching Hainan summer.” Wang Lihong (王荔蕻), the retired old lady whose Twitter activism roused the NGO community, was also “slightly overweight,” with round glasses and the air of a native Beijinger who “didn’t fear a thing.”

These female activists have generally received less coverage than male activists such as Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波) or Chen Guangcheng (陳光誠). This lack of attention is part of what drove Zhao to write her book. These were not superheroes in the ordinary sense, but, as Zhao maintains, these women accomplished just as much as their male counterparts.

Zhao Sile

BUT ZHAO SILE, also known as Alison Zhao, is also an activist in her own right. Born in Guangzhou, she grew up in the relatively free press environment of the cosmopolitan city, watching twenty-four-hour broadcasts of Hong Kong news channels. She watched with fascination the boisterous debates in the Hong Kong Legislative Council. The protests and demonstrations that took place in Hong Kong were seemingly commonplace.

Zhao professed a certain naivete, however, when it came to Chinese politics. Only when she began college at Nanjing University did she begin to realize “not only the difference between China and Hong Kong, but the difference between Guangzhou and the rest of China.” In Nanjing, her classmates were preparing for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) entrance examination. Becoming a Party member would open doors to work in government and state-owned enterprises. In Guangzhou, Zhao’s high school classmates mostly rejected joining the CCP for fear that it would hurt their chances of going abroad.

Xu Zhiyong. Photo credit: Shizhao/wikiCommons/CC

Xu Zhiyong. Photo credit: Shizhao/wikiCommons/CC

The turning point was Zhao’s 2011 study abroad in Taiwan. Keen to go into journalism, in the months leading up to her departure for Taiwan, Zhao sought to understand China’s “electoral” system. On the heels of the Tunisia-inspired 2011 “Jasmine revolution” and subsequent crackdown, several independent candidates put their name forward to run for basic level National People’s Congress seats. Among these was Xu Zhiyong (許志永), founder of the Open Constitution Initiative (公盟) NGO, as well as a former NPC delegate. In Guangzhou, Zhao also interviewed a number of college students who sought to run as non-affiliated candidates. Yet, eventually, in the self-described “biggest democracy in the world,” each of these candidates were prohibited from running by authorities. Officials in the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications voting district prohibited students from voting for Xu Zhiyong on the write-in portion of the ballot.

In Taiwan, the elections were different: contested and energetic. On the eve of the 2011 presidential election, Zhao recalls being able to pose a question to KMT candidate Ma Ying-jeou at a press conference and covering DPP candidate Tsai Ing-wen as she went to cast her ballot in her constituency. The room was packed with reporters and flashing cameras as Tsai made her way to the ballot box, a spectacle unseen on the other side of the strait.

After Zhao returned to the mainland, she threw herself into her reporting and eventually shifted to activism, becoming a staunch proponent of abolishing the custody and reeducation system (收容教育制度), which allowed for the detention and “reeducation” of individuals for up to two years without any due process.

This system largely targeted sex workers and those that solicited them. Yet it was sex workers that disproportionately fell victim to this “reeducation,” as rich and connected clients took advantage of rampant corruption and paid bribes of up to 100,000 RMB to escape long-term detention. Zhao worked to publicize these abuses of power, even filing suit against the Guangdong Provincial Public Security Office. For her work, Zhao has received numerous Hong Kong Human Rights Press Awards and other accolades.

The Cornered Beast Will Fight

ZHAO DIVIDES her book into two halves. The first part is named “Growing up in the Wild” (野蠻生長); the second, equally brutal, is titled with a four-character idiom kun shou you dou (困獸猶鬥), which translates to “The Cornered Beast Will Fight.” These activists did not have a sudden apostolic-style revelation to the evils of the Chinese regime. They were pushed to desperation in the face of injustice. Like cornered beasts, they decided to fight back, and grew into their own.

This is particularly true of the wives of the arrested 709 lawyers. On July 9, 2015, the domestic security services initiated massive-scale arrests of hundreds of China’s human rights lawyers and dissidents. Lawyer Xie Yanyi (謝燕益) was not at first arrested, but called to the police station for long periods of questioning. His wife Yuan Shanshan (原珊珊) watched out of the window, awaiting his return, “Nearly unable to breathe, constricted by ominous premonition.”

Photo credit: 钉钉/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: 钉钉/WikiCommons/CC

On July 12, Xie returned home after midnight, but was summoned again to the police station in the early morning. Xie didn’t return. When Yuan suddenly saw some twenty-odd men gathering outside the apartment downstairs, she knew something was wrong. She rushed her two sons, eleven and eight-years-old, into their rooms, telling them, “No matter what happens outside, do not come out.” Plainclothes officers burst into the apartment and turned the house inside out, overturning chairs, confiscating documents, books, and electronic materials. After the departure of the officers, she opened the door to her sons’ room. During the hours-long search, her children hadn’t dared come out to use the restroom and had urinated on the floor. The room stank. Yuan Shanshan burst into tears.

Wang Qiaoling (王峭嶺) wife of another lawyer Li Heping (李和平) was more calm. She believed that China was “a nation with the rule of law.” When Li Heping was arrested, Wang was sure that she, as his family, would be notified within forty-eight hours of his arrest of the charges against him, in accordance with Chinese law. Two days later, nothing.

Worried, Wang Qiaoling went to the Tianjin City Public Security Bureau and called on Li Heping’s younger brother, also a lawyer, for help. But every officer they talked to gave them no information. A few days later, Li Heping’s brother was arrested. Only ten days after her husband’s disappearance did she find out the charges against her husband—in a state-media Xinhua news article: “Public security officials had arrested lawyers in various locations that were implicated in inciting disorder and other serious crimes…in the name of ‘human rights,’ ‘justice,’ and the ‘public interest,’ these individuals had sought to undermine social order.” They would later be charged with the crime of attempting “subversion against the country and government.”

The police had engaged in three rounds of arrests and issued broad notices to the human rights community threatening them not to seek help for the arrested, “Or else their personal safety would be in danger.” Wang Qiaoling was furious. She filed a suit against Xinhua for defamation, but the suit was rejected. After the suit, she was summoned to the police station. Officers threatened and harassed her, ordering her not to cause more trouble.

Wang later lamented, “If I had received the appropriate notices from the police within forty-eight hours, if they had allowed a lawyer to see Li Heping, even if the charge was ‘overthrowing the government,’ I probably wouldn’t have become an activist.” Her faith in the system had collapsed.

These events transformed Wang and other wives of arrested lawyers into “resisters” (抗爭者). Wang began traveling around the country and meeting with other family members, encouraging and comforting them, telling them that their spouses or fathers had been arrested because they had done the right thing. Teaming up with Li Wenzu (李文足) and others, she stood in front of the Tianjin petitioner’s office with red plastic buckets, with white-taped messages in support of the detained lawyers. This “red bucket” activism later became a symbol of their fight for freedom. She even appealed outside of China, bringing attention to international media and human rights groups for help.

In the past, Wang would quarrel with her husband, calling his legal activism “extreme” and unnecessarily bringing trouble to their family. After he was arrested, she would often cry in desperation, saying that she now understood why he fought so hard against the system. Further consolation was being told that her husband was arrested for doing the right thing—his work in the anti-torture movement and protests against the miscarriage of justice cases. As she met with other relatives of 709, her fight for justice soon grew larger than Li Heping. Later, when public security detained her and asked if she would stop her activism if they released her husband, she refused. As Zhao says, “she was no longer the wife of a political prisoner, fighting just for the release of her husband, she had become an independent activist in her own right.”

Wang and all of the activists in Her Battles have similar stories of what Zhao terms “essential contributions” to civil society in China. Wang Lihong’s (王荔蕻) Twitter activism led to the first organized street demonstration since Tiananmen, protesting the arrest of three Fujian protestors, who were exposing police cover-up of the gang rape and murder of Yan Xiaoling (嚴曉玲) in 2008. After the Wenchuan Earthquake, Kou Yanding’s (寇延丁) skillful management of relations with public security allowed her to be one of the only NGO workers who could go on-site to help and collect records from injured children. Ye Haiyan (葉海燕) seized on the feminist movement to use the burgeoning internet as a platform to resist what Leta Hong Fischer calls China’s “patriarchal authoritarianism.”

But reading Zhao’s book is bittersweet, as we see the apex of female activism in China and its nadir as they encounter the all-too-common consequences of activism—house arrest, forced disappearances, harassment and detainment by police, constant surveillance, and social ostracization. The two most common criminal charges against activists are “inciting subversion of state power” (煽動顛覆國家政權) and “picking quarrels and inciting disorder” (尋釁滋事). These women are still alive, some abroad, some quietly in their hometowns, but their prime has passed. Their activism has slowed to a murmur, awaiting a new generation of activists to emerge.

Civil Society and NGOs

LAST MONTH, I asked Zhao Sile about the prospects of the women’s rights movement in China in 2020, particularly after the recent #MeToo case in Beijing. On December 2, Zhou Xiaoxuan finally had her day in court after accusing prominent television host Zhu Jun of sexual assault. Hundreds showed up on the cold Beijing morning to show support for the 28-year-old, only to be quickly dispersed by the police.

But Zhao is not optimistic. Today, she says, “from a civil society perspective, collective power is not as substantial and comprehensive” as before. Feminist movements in China had their heyday from 2012 to 2015. Spearheaded by NGOs like the Yirenping Center (益仁平中心), Female activists and organizations were able to organize and advocate. Activists walked thousands of kilometers on foot to deliver a petition to Beijing to include Hepatitis B treatments in medical insurance plans. Taking inspiration from the “Occupy Wall Street” movement, female activists organized the “Occupy Men’s Restrooms” movement to increase the share of women’s public restrooms. “Art activism” became a medium to express the desire for social change. In 2012, activists across different major cities dressed up as “injured brides” in bloodied wedding gowns to protest domestic violence.

Cover of Her Struggles

Cover of Her Struggles

This brand of activism seems harmless enough. Yirenping was viewed as one of the more moderate and nonpolitical NGOs. They mainly focused on discrimination of minority groups, such as those infected with Hepatitis B, the disabled, and residence-based discrimination. By contrast, an NGO such as the Open Constitution Initiative was seen as more politically potent and “dangerous,” taking a more activist approach and working on sensitive cases with human rights lawyers like Teng Biao (滕彪) and Xu Zhiyong.

Yet, in 2014, when Xi Jinping rose to power, the new government cracked down harshly on NGOs, which Zhao covered extensively. Prominent NGOs like Yirenping and Open Constitution were shut down. It didn’t matter how “moderate” the NGO was. Influence and organizational power were enough to grate on the nerves of the Party. Foreign NGOs were booted out, and the CCP systematically infiltrated other NGOs by requiring them to have a Party committee—turning them ironically into “government-owned non-governmental organizations.”

Zhao gives me an analogy to describe today’s civil society in China: “It grows like moss and sings like crickets” (像苔蘚一樣生長,像蟋蟀一樣唱歌). Civil society does not have the ability to grow tall and sturdy like a tree, she explains, but like moss, it remains limited but alive. Activism has become more muted, singing only for themselves and their peers, like crickets, to send out the signal that there are still others like them.