by Thomas Batchelor

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Kubilayaxun/WikiCommons/CC

ONE DISTINCTLY pervasive, and shockingly permissive, form of genocide is that of cultural genocide—in particular, the extinction of languages, whether actively by force or as a set of passive policies. Over 6,000 languages are spoken today; almost 3,000 of these are classified as endangered on the EGIDS scale. Linguistic genocide whittles away at bits and pieces of society until there is nothing of a people remaining, though they may physically still be there. This has happened and is happening, all over the world, often with support from not just the cultural supremacist right, but self-declared left utilitarian developmentalists as well.

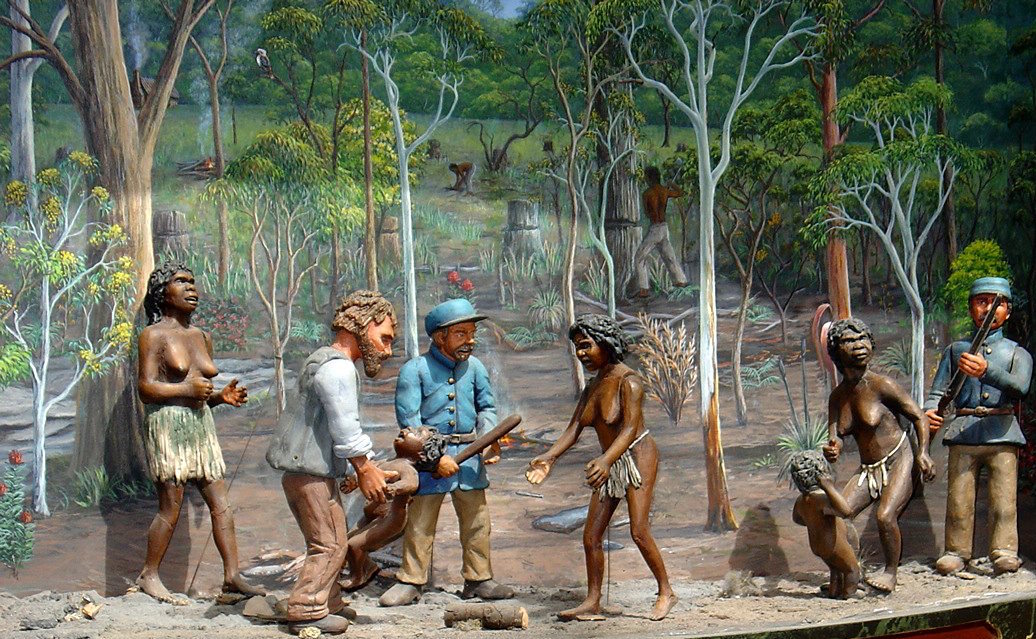

Perhaps the most salient example of linguicide is what historically took place in Australia. On the eve of Invasion by European settlers in 1788, at least 300 languages were spoken across the continent. Today, fewer than twenty are considered stable. This was achieved through not just genocidal policies targeting Indigenous Australians over at least two centuries of violence, but also the breaking up of Indigenous families. The policies that resulted in the Stolen Generation, done with the explicit intent of “breeding the black out” by the Northern Territory “Chief Protector of Aborigines”, saw mixed-race Indigenous children taken from their parents and placed into white families from a young age, separating them from their country, language, and kin. On many missions in the north, where many were forced to flee by the violence, children were explicitly banned from speaking in their native languages to one another.

Depiction of the Stolen Children on the Great Australian Clock in the Queen Victoria Building in Sydney, by artist Chris Cooke. Photo credit: Bjenks/WikiCommons/CC

Depiction of the Stolen Children on the Great Australian Clock in the Queen Victoria Building in Sydney, by artist Chris Cooke. Photo credit: Bjenks/WikiCommons/CC

It takes remarkably little to destroy a language. If you can halt transmission to younger generations of a population, it will simply disappear as its speakers grow old and eventually pass away. Active policies of linguicide can do this through murder, criminalization, or simply taking away the ability to transmit the language. These have been especially common in colonial societies, like Australia and Canada, and done with a justification of cultural superiority and a civilizing mission over the “barbaric” tongues of the natives. But active policies are not the only way to kill a language. Passive policies of linguicide and cultural assimilation are even more common in the 21st century, and regularly flies under the radar of the left, if not supported as a supposedly utilitarian purpose.

As happened in the USSR with the promotion of Russian as a pan-cultural language at the expense of other languages, in recent years China has increasingly pushed the same ideas in the many areas of the country that do not speak Mandarin natively. Nominally, Chinese law protects the use of minority languages in areas of titular ethnic autonomy. This has precluded the use of active measures against minority languages, but this does not prevent passive measures from being introduced, eroding minority languages’ places in public domains, and instituting assimilatory education policies.

Education is one of the key ways that one can either actively or passively kill a language, owing to its key role in youth development. In Xinjiang, there are currently three types of schools that children can attend; minority language medium schools, bilingual schools, and Mandarin medium schools. Increasingly in China, bilingual schools have been promoted to replace the minority language medium schools in areas with large minority populations. Furthermore, bilingual schools are only intended for minority students; there is no expectation of Mandarin-speaking Han students needing to acquire a minority language. This monodirectional multilingualism erodes the position of the minority language in favor of the dominant language.

This is done with the justification that Mandarin is the standard, common language of China. If one wants to get anywhere in life, they must use Mandarin. On the left, some accept this argument; what could be bad about a common tongue between all peoples? Minority languages are just an impediment to communication between peoples, after all. But this neglects the role that language has in culture; it is through language that stories and traditions are transmitted, that you speak to older generations in, that cultural knowledge is passed down through. As another colonial parallel to China’s policies in Xinjiang, this assimilatory thinking sees parallels in the few efforts of Kriol-English bilingual education in northern Australia. In its brief existence, it offered many Indigenous students a chance for education in a medium that was their native language, whilst also allowing English to be acquired on equal terms. This was not enough for state authorities, who began cutting hours of Kriol medium classes, before scrapping support for Kriol education altogether. Thanks to grassroots efforts more recently, however, Kriol is slowly becoming more prominent as the largest language spoken exclusively in Australia.

China appears to be following a similar trend; the gradual erosion of Uyghur through a unidirectional bilingual education system, funneling minority students towards a Mandarin-dominant society. In this view, the minority language is merely an impediment to be overcome in the formative years of youth. To counter this view, one might also notice that Chinese state media regularly promotes its minority cultures through cultural tourism and dance displays. These contribute to linguicide as well, behind the façade. At the same time as marginalizing the presence of minority languages in domains of common everyday use, the state opts for a strategy of folkorization for the public, whereby language is represented as a source of ethnic entertainment, rather than a serious language for use in the classroom or in business.

Entrance to a school in Urumqi. Photo credit: jun jin luo/WikiCommons/CC

Entrance to a school in Urumqi. Photo credit: jun jin luo/WikiCommons/CC

This is not to say that bilingual education or the promotion of a lingua franca is an inherently assimilatory method of linguicide, of course. Humans are a naturally social species, and that means a naturally multilingual one too; monolingualism has become a norm only in the modern era, in the aftermath of hegemonic powers asserting cultural dominance over others by force. Bilingualism can and has been done in a way that produces what we call a diglossia. A diglossia is a situation where two languages coexist with one another in a stable bilingual community. Often, the languages are covertly assigned different roles in society, where one that is more prestigious, usually the dominant one, is commonly used in official activities, for example, and the less prestigious, less dominant one used at home and in cultural events. This manner allows for minority language speakers to fully enjoy the use of their language, without locking them out of wider society.

The cause of endangered minority languages has regularly gone under the radar of many in the western left, either through lack of awareness or because of the often subtle nature of the suppression of minority languages. Whilst on the right, anti-minority language policies are driven through senses of cultural supremacy, and regularly result in active, overt and extremely harmful policies, denial and promotion of linguicide on the left takes a more utilitarian form. It is often seen as simply the by-product of the development of a society, that is, the destruction of barriers for communication, something that is compared with the borders of nation-states. How useful would it be if we all spoke the same language? But where nation-states exist in a mutually exclusive manner, many languages can inhabit a single person—something that is not to the detriment of anyone, but to the mutual benefit of the cultural diversity of the world.