by Alex Chuang

語言:

English

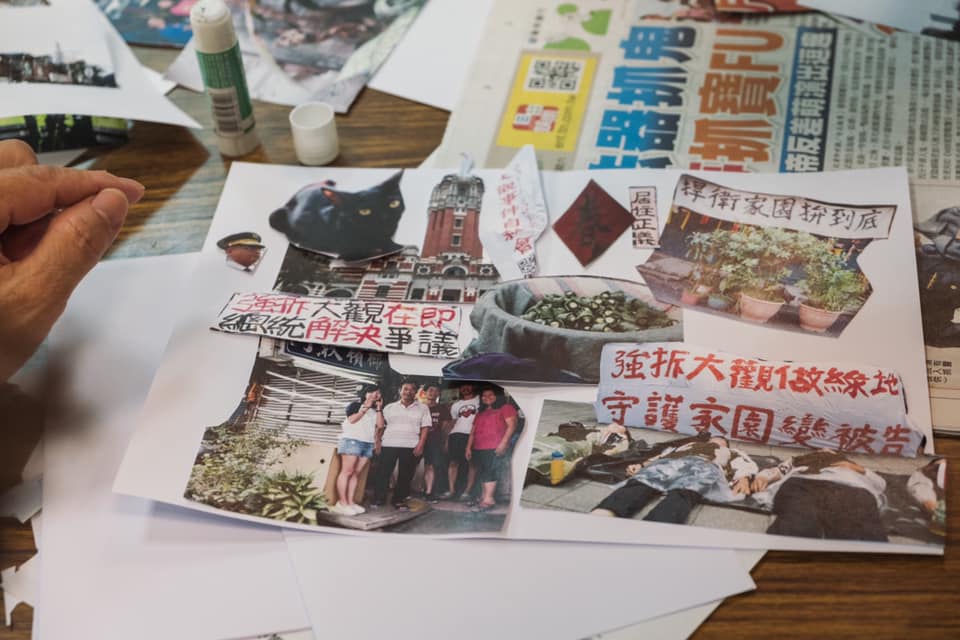

Photo Credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

ZHOU XIANG-PIN squeezes and nudges a black and white kitten, crooning in a voice worn by cigarettes and protests. “This one’s really sai nai, but if you touch him too much he’ll bite you. It really hurts!” she says, continuing to fondly ruffle the cat’s fur. [1] Up until last month, Zhou and her seven small cats were some of the remaining residents resisting eviction in Daguan, a military dependent’s village in the Fuzhou-Banqiao district of New Taipei City. Zhou was an active member in the collective of residents that mobilized continuously to fight against their eviction. Reflecting on the fight, she said, “It’s like an ant trying to bite an elephant — it’s almost impossible. But we still have to do it. If we don’t have our homes, we have nothing.”

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Over the past 80 years, the neighborhood has evolved and transformed, from its beginnings as temporary housing for KMT soldiers; to its later iterations as a marketplace, a site of affordable housing for immigrants and rural-urban migrants; and finally, the battleground in the urban poor’s fight for their homes. The vast majority of Daguan’s residents were the families and descendants of the original veterans, immigrants from China who married KMT soldiers or found cheap housing in the neighborhood, or Taiwanese who moved to the north due to economic hardship during industrialization in the 1970s. After decades of working and residing in relative peace, residents were sued by the government for the illegal occupation of land in 2008, prompting residents to organize into a self-help group that engaged in several years of escalating protest and negotiation.

Despite intense demonstrations demanding a fair resettlement plan in front of the Executive Yuan, Daguan was finally demolished in early August. Although residents will receive 360,000 NT in compensation, the negotiations failed to produce offers of resettlement aid. The conclusion to this battle marks a devastating moment for both Daguan residents and Taiwan’s land justice movement. Not only have most residents lost a major financial investment and source of income, but the eviction has severed their deep connections to the cultures, relationships, and memories that have been cultivated in the neighborhood for over seven decades. Daguan residents’ contestation of space has not only been a community’s fight for their homes; as a predominantly working-class, immigrant, and elderly community, the movement has taken strides to control their own narrative and assert their humanity against a government that continues to erase the urban poor with its actions. It remains unclear what the fate of Daguan residents will be; the vast majority of them are unable to afford to rent other apartments, and the government has failed to offer a proper resettlement plan.

Residents’ houses and family businesses may be gone for good, but the buds of knowledge and power that emerged through their resistance will continue to bloom and grow. In the five months that I spent around the neighborhood, I saw messy and brilliant confluences and contradictions—namely the unexpected meshing of non-resident college-age students fighting alongside older residents, and the lessons and potentials these held. Like any movement, Daguan faced clear limitations, including the urgent threat of eviction, the complexities of navigating class and power dynamics between outsider and resident organizers, and the omission of a settler colonial analysis. The last point of indigenous sovereignty has been and continues to be salient as long as Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and lands are still exploited, manipulated, and controlled by the Taiwanese state. While I noticing these areas where the movement needed to grow, I also believed in its strength, seeing it in the deep intergenerational relationships built between residents and students, the diverse tactics used to both challenge power externally and grow it internally, and the movement’s ideological groundings in networks of land justice struggles.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Now, a month and a half after the eviction, I write this article in an attempt to honor the devastation, struggle, and power that Daguan residents continue to experience and hold, as well as reflect on my brief participation in the movement while studying abroad in Taipei. In addition, as a young Taiwanese American, I hope this story invites my ethnically Han Taiwanese American friends to continue to interrogate their relationship to this island they might call home(land): What is a home that mercilessly destroys the homes of people already struggling to survive? What is a home that was violently stolen and never ours to begin with?

Taken Homes, Taken Memories: Land Expropriation and Land Justice

STATE-SANCTIONED land expropriation, urban renewal, and gentrification dating back to the 1040s to 1960s lay the foundation of the Daguan incident. While land reform policies implemented by the KMT during that time period have been viewed as the foundations of Taiwan’s modernization and economic development, these policies also set a precedent for reliance on buying, selling, and manipulating land usage for the purpose of economic development, relieving debt, and solidifying political elites’ influence and power. Daguan not only exists within the lineage of struggles against land appropriation in Taiwan, but it also belongs to the pattern of anti-eviction fights occuring in military dependents villages and informal settlements over the past several decades.

Since the 1996 Act for Rebuilding Old Quarters for Military Dependents, military dependents villages have become targets for demolition and redevelopment. However, Daguan’s specific history explains its treatment as an informal settlement, a status that has prevented it from claiming protection based on historical significance or attaining legal rights to resettlement aid. After several decades of living in the neighborhood with almost no communication from the government, the area was redesignated as “social welfare land” in 2002 without notice to the residents. In 2008, residents suddenly found themselves facing eviction orders and fines for five years of “illegal occupying public land.” The monthly fees residents faced often amounted to one-third of what was in residents’ bank accounts, adding to residents’ already existing financial pressures.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

“Even though our business isn’t always good, we just keep on doing it to stay afloat. If we’re evicted from this area, there’s really nothing left. Our lives will be in shambles,” Lin Yan-Yu states as she sits in her shopfront, deftly wrapping betel nuts in their leaves in preparation for tomorrow’s sale.

Yan Yu, her husband, and her two kids have lived in Daguan for thirty years now, making a living from selling betel nuts out of their bottom floor. The couple originally came from an agricultural village in southern Taiwan, and were pushed to the north to escape poverty and the devastating impacts of a typhoon that destroyed their harvest one year. For Yan Yu’s family and many other residents, Daguan was a vital source of financial stability. It was a place that residents invested in emotionally and financially, from migration, homeownership, and entrepreneurship, to engaging in determined protest and mobilization. Not only has the eviction stripped families of their primary income source, but it has also torn residents away from the precious community, memory, and culture that became embedded in the fabric of the neighborhood throughout the decades. For some, the relationships—both recent and life-long—that had bloomed in Daguan’s narrow alleyways were an essential part of daily survival and emotional wellbeing for the neighborhood’s working-class residents and families.

“My father’s imprints are all over this house,” Zhou says as she points towards the chair across from me. “He would sit right there and watch TV a lot. Now he’s right there.” She gestures to a cabinet with a box on top of it, surrounded by fruit and incense. ”That’s where my father lives.”

Zhou has lived in her narrow two-story home in Daguan since birth. As we sit in her living room eating porkchop biandang, she recounts bits and pieces of her childhood. Her late father’s background aligns with other earlier residents of military dependents villages: at nineteen years old, he immigrated from China to Taiwan with the KMT. After becoming a military instructor, he eventually settled in Daguan, where the family has remained for sixty years. At the time, the neighborhood was a thriving vegetable market, where Zhou’s mother sold red bean soup and tang yuan alongside other family businesses.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Despite the evident fondness Zhou has for the house (she asserts that no other space is as convenient and lets her come in and poop immediately after parking her scooter outside) there are still glaring issues. We walk up narrow stairs to see a large room with broken roofing that Zhou says it’s too expensive to fix—especially because they could be evicted at any moment. This situation was not unique to Zhou’s family; several Daguan residents lived for several years with broken appliances, unable and unwilling to put out costs that could be worthless in the end.

While it’s important to understand Daguan’s eviction case within the structural and historical context of state land grabs in Taiwan, Daguan’s significance also lies within its embodiment of resistance; that is, its role as part of the wave of land justice organizing that has taken place in the past decade. Protests around the Dapu township for the development of the Zhunan Science Park, as well as the expropriation of Huaguang community in Taipei are two prominent examples. The movements that grew in resistance to these eviction cases have heavily influenced the tactics and strategies used in later social movements, from the Sunflower Movement, to more recent land justice movements like Daguan.

How to Grow Collective Power: Strategy and Tactics

FOR THE STUDENT organizers, the history of land justice movements clarified Daguan as a site of a broader spatial struggle—an assertion of urban poor communities’ humanity against a developmental state and an obstacle to economic growth. “Were fighting a war of position,” Zheng Zhong-Hao—one of the core student organizers—says. “The larger political hope is that the current dispute will grow into an even larger political and ideological force that has the means to challenge the government.” These ideological groundings were deeply connected to Daguan’s relationship with the Taiwan Land Justice Action Union, a grassroots organization that originally sent Cynthia Tang—another prominent student organizer—and Zheng to organize in Daguan.

As a hub that connects different land struggles together, the union and its alliances wove a strong thread of solidarity and mutual support throughout the Daguan movement. Daguan also had close ties with labor movements, through students’ university organizations connections with labor unions, or their own work within labor unions themselves. The networks and ideologies surrounding the movement have not only been essential to situating Daguan in the longer trajectory of struggles for economic and social justice in Taiwan, but have also shaped the movement’s approaches to organizing.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

More specifically, Daguan’s strategy directed action in two concurrent and corresponding orientations: one faced outwards to publicly and vocally challenge state power, and the other sought to build community power and resilience from within the neighborhood itself. These two orientations worked in tandem, propelling momentum forwards in pursuit of the long term goal of consolidating political power among a broader movement.

Daguan’s usage of direct action and the occupation of public space are a clear remnants of the style and politics that previous movements have utilized to challenge the state. Compared to other ongoing land justice movements, Daguan was particularly known for its frequent and intense actions. Arrest was common and even expected. Zheng and Tang, two of the most vocal and belligerent voices during actions, became repeated targets of the police, frequently being arrested, pushed into cop cars, and injured during protests.

Like previous movements, protests and occupations served to delay demolition and blow up eviction cases in media. However, Daguan’s ability to engage media was always somewhat uncertain, as they have had trouble attracting enough positive media attention, despite the amount and intensity of their actions. Whether or not they were able to successfully attract media, these protests still played a crucial role in mobilizing a broader base of supporters into action and intervening in politicians’ narratives of democracy by calling out the hypocrisy and violence of attacks on the urban poor.

Actions were also a major point of political activation for residents, presenting folks a chance to speak their stories, subvert negative claims about residents’ motivations for protest, and assert agency by directly confronting the systems of power that threatened their homes and livelihoods. “Something that I learned through all of this was that you have to attack the king directly,” Xiang Ping told me as she recounted a particularly intense protest in early August of 2018, when residents and supporters rushed the Presidential Office building and demanded Tsai’s explicit support of a just resolution to the conflict. “It made big news, because we were able to aim for the president and get a response…I knew the action had let residents see the dawn of a new era. I saw it too.”

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Loud protest and direct action were only a couple of the movement’s tactics. Beyond confronting state power head on to demand an end to the eviction, the movement had clear intentions to build power within. These were demonstrated through their dedication to several goals: to establish deep connections between residents, student organizers, and outside supporters; use art to grow diverse base of support and uplift powerful narratives of the urban poor; uplift the leadership, agency, and collective power of Daguan residents; and contribute to building a more connected land justice movement in Taiwan.

Art production stands out as a key tactic the organizers relied on to gain traction and attention. Every action, every rally, and every day I was in the neighborhood, Cynthia—one of the student activists involved in the struggle—would have her DSLR out, documenting the residents daily lives in high definition. Daguan residents’ Facebook and Instagram pages are filled with powerful pictures and videos, carefully edited and pieced together by their media team. Neighborhood tours and mixed media exhibitions highlighted residents’ daily lives, household profiles, and the legal and physical struggles against the government. These projects were just a few of Daguan’s creative efforts to uplift personal stories of unjust displacement and collectively frame their own narrative.

Music was also an essential element of the movement’s popularity, especially among young creatives and radicals. Trapped Citizen (愁城), an anarchist DIY art and music collective based in Taipei, was a consistent and key collaborator, providing sound equipment, musicians, merch design, and a larger platform for arts events held at the community. For better or for worse, these alliances and events cultivated a particular crowd and political aesthetic, one characterized by hair-dyed black-leather-wearing twenty-somethings congregating at the movement space.

It was a peculiar sight, juxtaposed with Daguan’s working-class residents and families in the backdrop. It’s possible these event spaces were intimidating and alienating to folks who don’t seem to fit in. But to counter the claims of cranky local critics, it’s important to mention that Daguan’s young student supporters didn’t protest just to protest. This crowd wasn’t supposed to be, nor was it the face or heart of the movement. Instead, it was a strategic base—built through the movement’s creative endeavors—there to blow up the movement on social media, provide resources and manpower, and show up in critical mass when shit went down on the streets.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Who truly lies at the core of the movement then, are the residents who have fought tirelessly for their homes, and the student organizers who joined along the way. The relationships between residents and students woven together throughout the course of the movement are the foundation of a larger commitment to building collective power. Through community organization, political agitation, leadership development, collaboration with legal professionals, and campaign strategizing, Daguan residents and students have contributed to a growing land justice network much larger than themselves.

Complexities and Limitations

“When [the students] first came [to Daguan], I really hated it. I stood at my door and yelled at the students, ‘You’re only here to fulfil your own interests. You’re not needed, so please leave.’” – Xiang Ping

IT WASN’T EASY to build the relationships between Daguan residents and student organizers that exist today. It’s important to acknowledge the internal messiness and complexities accompanying the residents and students’ differing material conditions, stakes, and motivations for participating in the movement. As Xiang Ping’s initial reaction reveals, some residents rejected the outside help when students first arrived in the neighborhood, wary of opportunist young activists in pursuit of fame.

Over time, the students’ intentions became clearer. “[They] kept on protesting alongside the younger Daguan residents, until in the end, I saw their commitment and hard work. That’s when I began to step out with them and protest too,” Xiang Ping recounts. “Now, we don’t consider Cynthia an outsider. We see her as a part of us, part of our family.”

For the students, the dynamics with residents have always been complex. Zhong Hao asserts that “Organizers need to be very self-aware and constantly reflect on their role in the struggle. We have to ask ourselves, are we making decisions in accordance to the interests of the group? We spend so much time forming relationships and communicating with the residents, because that’s the only way we’ll understand their voices. It’s imperative for residents to seize and grow their own power.”

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

The work of building collective power and opening space to uplift residents’ agency was necessarily consistent and physically rooted in the neighborhood. More specifically, the organizing was grounded in the weekly self-help group meetings at “No. 40”, the garage space that the movement had turned into their organizing hub. Every Saturday at 7 PM, without fail, Cynthia would rap on residents’ doors, shouting through the window to ask them if they were coming to the meeting. Even though the resident took their time to show up, in the end, they always did. While meetings individually weren’t always profound or invigorating, they opened up crucial space for residents to connect their experiences of struggle to the structures of power they were facing, thus creating the foundations for to organize more powerfully in the future.

It would be inaccurate to say that the dynamics were perfect all the time—sometimes meetings would consist of Cynthia talking for an hour while residents started to doze off, and other times no one would volunteer to speak at the upcoming press conference or to even show up to the next event. Despite their best intentions, the unwanted power dynamic of “guiding” that Zhong Hao spoke of did seem to appear frequently, especially in the way students directed meetings and planned campaign strategy. I’m curious how the movement could have further honored the residents’ agency and ability to grow, and centered the slow work of political education and leadership development to match folks’ genuine needs and interest.

Still, It’s important to note the limitations and conditions that could have made the process more difficult—namely the urgency of the impending eviction, which gave reason for continuous rapid mobilization and stunted the movement’s capacity to hold both long and short term goals simultaneously. In addition, most residents worked long hours and received backlash from their employers after taking time off to engage in protest. Students keeping up with organizing while managing heavy course loads had developed a series of coping mechanisms, including heavy cigarette smoking, bad eating habits, and frequent all-nighters. It was limitations like these that drastically impacted how residents and students showed up in the space, and more broadly, their ability to imagine and practice a more visionary trajectory of land justice.

Expanding Land Justice Trajectories: Land Justice, Internationalism, and Settler Colonialism

THROUGH MY perspective as a Taiwanese American and student organizer, I noticed two potentials for transformation and growth in Daguan’s organizing that could be relevant to strengthening the land justice movement. Despite their Marxist leanings and connections to organizers with networks all over the world, the movement was unable to prioritize establishing connections of international solidarity and collaborating with struggles for land justice outside of Taiwan.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

While their insularity may have been a product of fighting the urgent threat of eviction, the opportunities they were given to network with international coalitions could have expanded and transformed the power of their organizing to ignite a larger and more radical scale of change. Thus, it may be critical for future anti-eviction movements in Taiwan to interrogate how they will practice internationalism and fit within international-scale networks for global justice.

Secondly, Daguan could have further centered an anti-imperialist framework—not just in their approaches to international solidarity, political education, and political messaging—but especially in how they addressed Taiwan’s own history of internal colonization. Whereas Daguan understood their eviction through the lens of class and capital, identifying it as part of larger patterns of urban renewal, gentrification, and Taiwan’s position as a developmental state, indigenous movements for land justice went even deeper, asserting the necessity of anti-colonial anti-eviction movements and rejecting the commodification of land. Daguan’s omission of the history and current realities of indigenous land expropriation calls for the interrogation of how frameworks of settler colonialism are deeply intertwined with land injustice in Taiwan. In other words, in order to truly move towards their vision of building a united front of land justice movements, there must be a radical reframing of land justice for non-indigenous anti-eviction movements.

Since the beginning of settlers’ arrival on the island, Indigenous peoples have continuously faced land dispossession as a tool of Han settler colonialism and control. Even after the initial colonization and confinement of indigenous peoples, later waves of assimilation, the nationalization of indigenous land, and industrialization destroyed the financial stability of indigenous peoples in rural eastern Taiwan, causing them to sell their land, leave their indigenous villages and migrate to the cities. The land was often left to Han Chinese, the government or corporate entities to exploit the region’s natural resources. To be clear, this process of land dispossession is ongoing, visible in the way indigenous communities continue to be violently uprooted in urban spaces.

We cannot ignore that the logic of disposability Daguan faces as an urban poor community is connected to the deep threads of settler colonialism that make up Taiwanese society itself. However, the Han residents in Daguan do not face the same racialized colonial logic that follows indigenous peoples wherever they go. Daguan as a movement must contend with the reality that the home they fought so fiercely for is and remains stolen land. For the ethnically Han Taiwanese Land justice movement—and for me, a two-time-settler-colonist from the Taiwanese American diaspora—what would it mean to center an anti-capitalist and anti-settler-colonial analysis in this work, one that sees Daguan as part and parcel of the larger resistance against global imperialism, both abroad and internally?

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless/Facebook

At the same time that the Daguan resistance was occurring, indigenous land justice organizers were continuing a 700+ day occupation on Ketagalan Boulevard, calling for the inclusion of privately owned land in the designation of traditional indigenous territory. It is the indigenous environmental and land justice movements’ calls for sovereignty and the decommodification of land that Daguan residents and organizers must learn from. By identifying systemic enemies and our intertwined struggles for liberation, we reframe the timeline. Daguan may be gone for now, but the battle is much longer than this. As we begin to see how our liberation is intertwined, more and more we come to understand that the fight against land expropriation, gentrification, capitalism, settler colonialism, and global imperialism must continue on.

[1] “Coquettish” or “spoiled” in Taiwanese.