by Patrick Huang

語言:

English

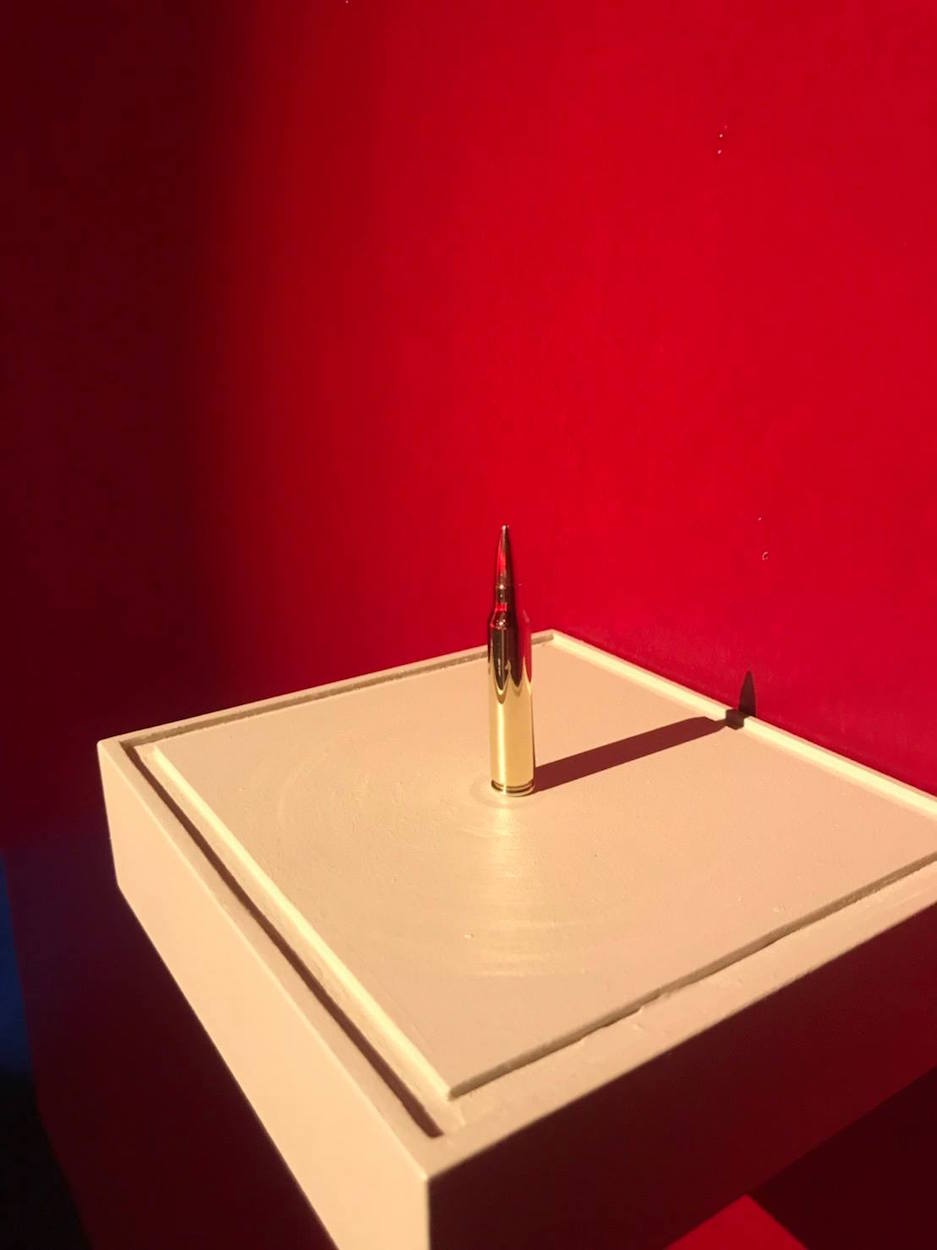

Photo Credit: Nutdanai Jitbanjong

Nutdanai “Nut” Jitbunjong is a Thai artist whose artwork largely focuses on representations of the “violence” of by governments and military regimes. The following interview follows up on an interview conducted last November. His exhibition, LOOT, will be shown at Gallery VER, in Bangkok, Thailand, from March 9th to May 11th, 2019.

Patrick Huang: Hi Nut, nice to meet you again. First off, congratulations on your show. You past projects focused on Thailand. Why did you change to a broader Southeast Asian focus this time?

Nutdanai Jitbanjong: I do not think it changed. Earlier, I’d sought to focus on the complexity of Thai politics and establish a picture of Thailand’s political structure. When I spent time musing on the pool of data as a whole, I found that Thailand and Southeast Asia have a broader, shared political structure. I still focus on the issues of rights, freedom, history and politics as I did in the past projects. But this time it expanded to a larger scale.

Photo credit: Nutdanai Jitbanjong

Photo credit: Nutdanai Jitbanjong

PH: How do you conceive of the relation between politics, human rights, art?

NJ: I think politics, human rights, and art are the things that the powers-that-be are trying to control, to use them to trick their people. As in, say, distorting history, creating the social values that they prefer, and educating people through these values. Yet they like to have their people still feel that their rights are freely available. Such leads to ideological dominance.

PH: Well, now please tell us about your work.

NJ: This work began with the observation that the governments of Southeast Asian countries have used their own people’s money, in the form of public taxes, to “kill” their own people. It also involves important issues such as the national budget, capitalism, and the political role of the army. These things affect the institutions of democracy in each country. We can notice that most of these countries have been semi-democratic, semi-autocratic for a long time.

PH: Your work features many bullets. In what ways do the bullets represent?

NJ: These bullets are of the standard sizes that the army of each country in Southeast Asia uses. We can say that the army’s principles are contrary to democratic ones. These are inconsistent with the principles of freedom. When the army takes a political role for such reasons as national security, nation-building or the protection of a royal institution, these situations lead to dictatorship. Bullets, then, are used on the citizens of a nation. These bullets represent violence. The process of gathering and creating bullets is to point to how the state has spent enormous amounts of money for their sole staying in power.

Photo credit: Nutdanai Jitbanjong

Photo credit: Nutdanai Jitbanjong

PH: Why is it important to make this artwork at this time and place?

NJ: I didn’t pay much attention to time and place. I’ve been interested in these social issues for so long and have been studying the issue for more than four years. After I collected enough data, the work came out as you see it.

PH: Can we say that this work is part of a political movement? Why or why not?

NJ: I don’t think it’s a political movement. This creative work that accommodates my points of view derives from research. Yet I insist that we should be aware of these social issues. Like the previous question about politics, human rights, and art. These are things that people deserve to know and be alert to.

PH: Last but not least, as a young artist, what do you hope to see in Southeast Asian politics?

NJ: I still believe in freedom and equality, although I was raised in the country which lacks these things. I do believe that all of us are born equal.