by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Maria Dyveke Styve/WikiCommons/CC

CONCERN WITH Chinese spying efforts or otherwise undue influence is on the rise globally, as can be observed in a number of recent incidents. But due to the fact that “western” and “non-western” countries are often thought of in separate mental frames, one has seen few connections made between such incidents in international media.

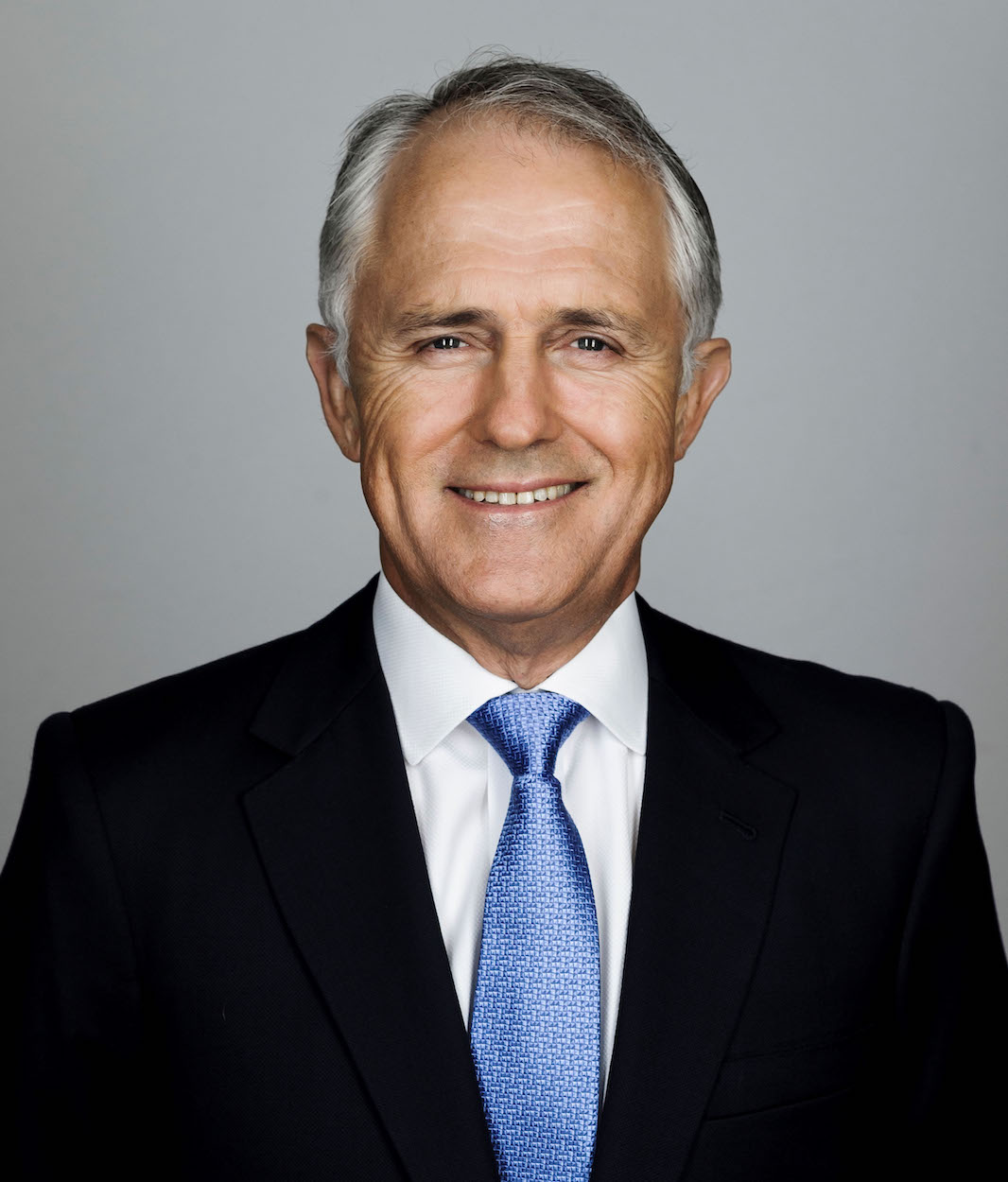

For example, after a number of high-profile incidents, including incidents of Chinese student organizations mobilized in protest against events critical of China, controversy regarding Australian politicians who may have accepted money from China, detention of Chinese-Australian academics during visits to China, Chinese influence in Australia is increasingly controversial. Prominent Australian politicians including former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull have, however, accused the media and society of leading a “witch hunt” against Chinese in Australia.

Malcolm Turnbull. Photo credit: Australian government/CC

Malcolm Turnbull. Photo credit: Australian government/CC

Although thought of as a “western” country, Australia is geographically close to China. Chinese influence over Australia, then, is not merely economic but also geopolitical. As a result, the recent rental of Darwin Port to the Chinese government for a ninety-nine year lease as part of a 506 million USD deal has also led to some anxieties that China will use this port not simply for commercial purposes, but to advance its more general geopolitical interests in the region, inclusive of claims over disputed islands in the South and East China Seas.

On the other hand, controversy in Africa recently broke out with accusations published in Le Monde that China had bugged the African Union headquarters in Ethiopia, the construction of which was financed by China. Although African Union officials have denied this, claiming that such claims are attempts to undermine productive Sino-African relations, this returns to many of the international concerns regarding large, China-financed infrastructure projects that China has offers to potential diplomatic partners as a means of courting them.

Apart from spying concerns, or worries that structures are shoddily built and will eventually prove hazardous, it is feared that China intends to use such structures in order to widen Chinese reach. Sometimes this is accused of being a form of “neo-colonialism,” given China’s use of economic means to advance its political reach.

Australia and other western countries seems to have generally avoided this spate of infrastructure building projects, seeing as China more usually offers these projects to non-western, “developing” nations. Controversy broke out late last year after Australian politicians lashed out against such projects in the Pacific as large yet poorly maintained, but do not usually include claims that China is “colonizing” such countries.

Nevertheless, it is increasingly a dilemma for many “developed” western countries as to what stance to take on such infrastructure projects, or otherwise how to deal with Chinese development efforts. We might observe in the case of the Darwin Port, this follows on the heels of numerous similar deals signed by China with African and Middle Eastern nations such as Djibouti, Pakistan, and elsewhere, as well as a successful Chinese bids to control Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka and the Greek port of Piraeus and last year.

Port of Piraeus. Photo credit: Nikolaos Diakidis/WikiCommons/CC

Port of Piraeus. Photo credit: Nikolaos Diakidis/WikiCommons/CC

In the case of the latter, China took advantage of Greece being cash-strapped due to ongoing financial difficulties, as well as how Greece felt spurned by the European Union. This likely points to a future model for China seeking to build closer ties with western countries by taking advantage of monetary troubles or diplomatic difficulties. The port of Piraeus is Greece’s largest port. But accusations that China is “colonizing” Greece have occurred less often because of that Greece is a western nation. Perhaps this returns to that the vocabulary of colonization comes less readily to western nations owing to that they have not experienced extensive histories of coercive colonization by larger countries.

Yet concerns about Chinese spying or undue influence seem valid in both the western and non-western world. Either way, between “western” and “non-western” countries, China is seeking to step into the position of power once occupied by western colonial powers on the global stage, particularly America, and this includes unduly influencing the politics of both western and non-western countries alike, much as America routinely does. Putting aside questions of whether this is “colonization,” very probably, however, conceptual difficulties for Chinese influence, will persist more readily among western nations, with the persistence of the view that they are not susceptible to Chinese influence in the same way as non-western countries. This, too, would be a product of historical uneven development.