A Comparative Examination

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Brian Hioe

Anti-Nuclear Politics as an Entry Point into Asian Activist Politics

IT WAS REMARKED to me during an interview that during a trip to Australia by members of Taiwan’s Green Citizen Action Alliance to learn from an Australian anti-nuclear NGO, while the intent of a trip was originally for the Taiwanese NGO to ask questions of and learn from the Australian one it instead became that the Taiwanese NGO was interrogated by the Australian NGO. After learning of the protest of 130,000 against nuclear power in Taipei in early March and the occupation of 50,000 on Zhongxiao West Road that took place in wake of the Sunflower Movement on April 27th, Australian anti-nuclear activists wanted to know about how such an event which would have been impossible in other contexts for the anti-nuclear movement was possible in Taiwan. In part, this is of course simply a result of that Taiwan is not very well known internationally, and so news events in Taiwan are not reported on internationally. But this raises questions of transnational activist politics and what movements in different countries can learn from another.

Anti-nuclear demonstrators near Jinfu Gate in Taipei on April 27th. On the back of two protestors is the “Anti-Nuclear Flag” ubiquitous to Taiwanese activism, which says in English, “No Nukes, No More Fukushima”. Photo Credit: Brian Hioe

Anti-nuclear demonstrators near Jinfu Gate in Taipei on April 27th. On the back of two protestors is the “Anti-Nuclear Flag” ubiquitous to Taiwanese activism, which says in English, “No Nukes, No More Fukushima”. Photo Credit: Brian Hioe

When we find ourselves in the situation of trying to point to lessons that social movements in one national context can offer to social movements in other contexts, the difficulty we rapidly encounter is that sometimes social movements are the product of particularities of their respective national contexts. In the sense that the Taiwanese anti-nuclear movement arose out of factors quite particular to Taiwan, and therefore the lessons of Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement are not entirely transferrable to other contexts.

What has gone unacknowledged about Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement to date is the critical role the anti-nuclear movement played as an incubator of the activist networks that eventually gave birth to the Sunflower Movement. Namely, the expansiveness of the anti-nuclear movement in activist politics was what later allowed for the all-encompassing nature of the Sunflower Movement, whereby the movement became something all-encompassing of society.

In the interests of considering the Taiwanese anti-nuclear movement as a case study into social movements in East Asia, we might venture comparisons. The 2012 Japanese anti-nuclear movement following the Fukushima incident in March 2011, what was then referred to as the Hydrangea Revolution, was no less encompassing of Japanese society as the Sunflower Movement was in Taiwan. However, where the difference between movements in both countries points towards certain differences between Taiwan and Japan, we can also derive lessons for activist politics in both countries, and for Asia more broadly, through a comparative examination of both movements.

The History of Taiwan’s Anti-Nuclear Movement

THE PARTICULARITIES of Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement lie in its longstanding nature. The controversial Reactor #4 in Gongliao as pushed for by the KMT and other government agents has been resisted for decades. While reactors numbers 1, 2, and 3, had finished construction by the mid-1970s, reactor #4 was controversial and thought to be especially dangerous on the basis of its use of mixed parts from different manufacturers, rising environmentalist concerns concerning the issue of nuclear energy the world over during the 1970s, as well as the energy crises of the 1970s. Though the construction of nuclear reactor number four was announced in 1979, construction beginning only in 1999, why nuclear reactor number four has not finished construction over three decades later is in part because of the continual process of construction starting then stalling because of public controversy.

Demonstrators on Zhongxiao West Road on April 27th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Demonstrators on Zhongxiao West Road on April 27th. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Yet so far as controversy over nuclear power dates back to the Martial Law period, such are the specificities of the Taiwanese anti-nuclear movement. The rising tide of anti-nuclear sentiment in Taiwan coincided with the rise of Taiwanese democracy movement in the 1980s. The announcement of the construction of nuclear reactor number four coincides with the 1979 Kaohsiung Incident, popularly held as marking the beginnings of the Taiwanese democracy movement and the Dangwai Movement to form a party outside of the KMT that eventually led to the formation of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

Critical figures in the democracy movement such as former DPP chairman Lin Yi-Hsiung, whose wife and daughter were killed by the KMT in 1980, also played a critical role. Apart from that in recent memory it was Lin’s hunger strike which galvanized 50,000 Taiwanese into the streets of Taipei against nuclear power in April after the Sunflower Movement, Lin pushed for public referendum about the issue of nuclear power in 1991 and has continued to do so in the present. Accordingly, so far as the demand for public referendum as a way to break the continued stronghold of KMT power over electoral politics and as a means to enact genuine popular democracy is one which continues to be mobilized up until today, we can trace part of the origins of the demand for public referendum to the issue of nuclear energy.

However, on the other side of the equation, nuclear power has also become a symbol of the shortcomings of Taiwanese democracy. Namely, the issue of nuclear power has gone on for so many decades without resolution, with continual resumption of work followed by stoppages, then followed by the resumption of work, nuclear energy has become a symbol of how Taiwanese democracy is without “effectiveness” or “inefficient.”

Loudspeaker truck normally used to broadcast anti-nuclear slogans being used to broadcast labor slogans on May Day of this year in Taipei. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Loudspeaker truck normally used to broadcast anti-nuclear slogans being used to broadcast labor slogans on May Day of this year in Taipei. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The contemporary anti-nuclear power movement is largely a two or three year development following the Fukushima disaster in Japan. More broadly, the contemporary Taiwanese anti-nuclear power movement comes out of the mass participation of young people in civic issues that began with the increasing politicization of the young that began after the 2008 Wild Strawberry movement. But what is unique to Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement, non-transferrable to outside contexts, is its connection with the past struggle for democracy during the authoritarian period. Nuclear power is an inherently politicized issue as a result from the previous struggle.

The History of Japan’s Anti-Nuclear Movement

IF TAIWAN’S anti-nuclear movement is particular on the basis of its relation to Taiwan’s democracy movement, Japan has a particular relation to nuclear energy itself. This, of course, dates back to the usage of the atomic bomb on Japan in 1945, in which the world witnessed the horrors of radiation sickness for the first time. In spite of that Japan was the first nation in which the harmful effects of radiation on the human body were illustrated to the world, guided by the auspices of American occupation and American political dominance over Japan which continued even after the end of occupation, nuclear power plants were constructed in Japan nonetheless in the 1960s and 1970s.

Anti-nuclear demonstrators on July 13th, 2012 in Kasumigaseki, Tokyo. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Anti-nuclear demonstrators on July 13th, 2012 in Kasumigaseki, Tokyo. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Resistance to nuclear power in Japan arose with the rise of anti-nuclear politics globally in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, seizing upon Japan’s history as having suffered at the hands of nuclear power. But the close relation of the energy industry and the state allowed for nuclear power to provide up to a third of Japan’s energy usage as a result. By contrast, Taiwan has never become so dependent upon nuclear power, an apparent paradox given that Taiwan has never suffered large-scale nuclear disaster the way that Japan has.

Though government cover-ups in the 1990s provoked controversy, nuclear power was largely not an issue for Japanese society through the 2000s until the 2011 Fukushima incident, in which the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami suffered by Japan led to a nuclear meltdown at three reactors in Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi power plant. The response by the Japanese government was disastrous; not only had the meltdown occurred in part because of inadequate safety measures and failure to maintain equipment, but the government sought to avoid responsibility and cover up what had transpired. This was perhaps most poignantly evident in attempts to downplay the amount of radiation contamination suffered by the young and the effect of radiation upon agricultural produce. What was also evidenced through government mishandling of clean-up efforts was widespread corruption, to the extent that because of difficulties in finding those willing to work as decontamination workers, homeless were rounded up by organized gangsters acting as contractors for decontamination work in 2013.

Yet the government refused to back down from nuclear energy policy. While nuclear reactors were shut down across Japan following the Fukushima incident, with the last of reactors going offline in May 2011, the aim of the Japanese government to start Oi power plants led to mass protest against nuclear power in the summer of 2012, with over 150,000 gathering weekly in late July in Tokyo for the largest set of protests Japan had seen since the 1960s.

But what is striking is that the Japanese anti-nuclear power movement only began over one year after the Fukushima incident. Moreover, the anti-nuclear movement was not successful in its demand of preventing nuclear restarts. Despite the outspokenness of the Japanese public against nuclear restarts, politicians would cite difficulties in meeting the energy needs of Japan and effects of Japan’s energy shortage on the economy as why nuclear power restarts were necessary.

Musical performance at an anti-nuclear rally in Osaka, Japan on July 28th, 2012. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Musical performance at an anti-nuclear rally in Osaka, Japan on July 28th, 2012. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

While reactors would later be restarted, reactors would go offline again in September 2013. However, the Japanese government would announce plans for restarts in 2015. So, the issue remains unresolved. Though the anti-nuclear movement would prompt politicians to pay lip service to the notion of phasing out nuclear power by 2030, there seems to be little reason to believe the sincerity of their words.

Structural Parallels Between Taiwan and Japan

WHAT WE CAN point to in both the cases of Taiwan and Japan are a number of immediate similarities where nuclear power is concerned. Nuclear power plants in Japan were constructed using parts by American manufacturers, using Japanese contractors. This was also largely the case the case in Taiwan, with parts provided by American manufacturers, construction undertaken by American or Japanese contractors, and the management of the reactor by state-owned power company, Taipower.

Yellow ribbons emblazoned with anti-nuclear slogans tied to a bridge overpass on April 27th on Zhongxiao West Road in Taipei. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Yellow ribbons emblazoned with anti-nuclear slogans tied to a bridge overpass on April 27th on Zhongxiao West Road in Taipei. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

We can more broadly suggest that the construction of nuclear power plants in East Asian countries with close ties to the US as Taiwan and Japan as occurring under the influence of the United States. This is a product of that the “East Asian Tigers” of East Asian capitalist powers outside of China are client states of the United States politically and, accordingly, come under the economic influence of the United States.

It would be, of course, be conspiracy mongering to suggest that American companies had a means to directly dictate Taiwanese or Japanese energy policy, although role of corporate interests is not impossible, and the Cold War saw at times the interchange of personnel between the corporate and government sector in the American government. But so far as Taiwan and Japan were in the “American camp” where foreign relations were concerned, as the advanced first-world western power that East Asian nations would turn towards for technology, it is not surprising that Taiwan and Japan would draw on the United States for the technology to construct nuclear reactors. As a nuclear power, the United States was a source for nuclear technology the world over. And seeing the world was divided into two camps during the Cold War oriented around the superpowers of the United States and Soviet Union, nations not allied with the Soviet Union would turn towards the United States for nuclear technology or vice-versa.

There are a number of interrelated factors that have allowed for the closeness of the state and energy industry in Taiwan and Japan. This closeness in turn has allowed for the defense of nuclear power by state actors in the face of popular resistance. In the case of Japan, whose political system was set up by the United States after its defeat in World War II, electric utility companies as TEPCO of Fukushima Daiichi infamy are privately owned, but, emerging from the state-owned power companies dismantled after World War II during American occupation, retain a close relationship with the state. At a point, despite TEPCO the world’s largest privately owned electric utility company, TEPCO employees were thought of as being akin to civil servants. This is at least partially because of America’s attempt to preserve Japanese institutions following Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War in order to shore up Japan as an ally against Communist China and the Soviet Union. By contrast, Taiwan’s Taipower is state-owned, formed by the KMT government in 1946 after the end of the Japanese colonial period, but the relationship of Taipower to the KMT state was that of state-owned enterprise and continues to be so today. Accordingly, one can point to parallels with Japan where electric utility companies with close relations to the state are concerned.

Anti-nuclear demonstrators in late July 2012 in Osaka, Japan, protesting KEPCO, which services electric power for the Kansai region. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Anti-nuclear demonstrators in late July 2012 in Osaka, Japan, protesting KEPCO, which services electric power for the Kansai region. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Namely, Japan and Taiwan after World War II were both one-party governments that were client states of the US, Taiwan only being more brutal than Japan insofar as that rule of the KMT was through martial law, military dictatorship, and direct ties to the party-state where the LDP was at least in theory a normal political party in an democratic government—albeit an democratic government dominated by one party. This set of geopolitical affairs was one which existed in various permutations through East Asia and the Asia-Pacific more broadly. Yet where Japan and Taiwan would follow similar economic developmental paths after World War II as two of the “East Asian Tigers,” no doubt the set of historical conditions which led to the similar economic development is also a factor in why both countries would develop a similar set of relations between the state and the energy industry where the entrenched interests of the energy industry are strong enough and have influence enough over the state that they are able to resist the oversight of state actors.

With parallels in structural conditions, it is not at all surprising that politicians in Taiwan or Japan have drawn upon similar rationales to defend nuclear power. So far as Japan or Taiwan have spent so much money constructing nuclear reactors, it would be too late to double back now. Moreover, pushed by the public, politicians in both nations have been forced to vow that someday, Taiwan or Japan will be nuclear free. But, of course, such words may just be and very likely are empty rhetoric. At other times, in particular Japan’s privately owned TEPCO more than Taiwan’s state-owned Taipower, it may be that politicians must also watch out for the corporate interests behind the energy industry that can affect their own political careers.

Activist Politics in Taiwan and Japan

IN CONVERSATION with documentary filmmaker Ian Thomas Ash, who I interviewed in Tokyo this past summer after meeting him in Taipei following the premier of his film A2-B-C in Taiwan, reflecting upon his observations of the anti-nuclear movement in Japan and his observations of Taiwan, he ventured was it seemed as though there were much more young people active in Taiwan than in Japan. Having come to Taiwan, its anti-nuclear movement, and the Sunflower Movement after experiencing the 2012 Japanese anti-nuclear movement, I did also think that was the case. Where the Taiwanese anti-nuclear movement had a critical role in what later became the Sunflower Movement, we can map both onto each other as expressions of Taiwanese civil society.

I account the strength of the Taiwanese anti-nuclear movement and the Sunflower Movement to the presence of networks and structures that led to the mass mobilization of young people and civic society actors. On the other hand, in participating in the high point of the post-Fukushima anti-nuclear movement in 2012, while there was the participation of civic society actors and the mass mobilization of young people what differed between 2012 in Japan and 2014 in Taiwan was that new structures and networks did not play a key role in the Japanese anti-nuclear movement because previously existing structures and networks were unwilling to cooperate at an integral level when that involved compromising long-held organizational identities and shifting tactics.

Japanese anti-nuclear art on display as part of the October 2012 exhibition, RadioActivity! Antinuclear Movements from Three Mile Island to Fukushima at Inference Archives in Brooklyn, New York. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Japanese anti-nuclear art on display as part of the October 2012 exhibition, RadioActivity! Antinuclear Movements from Three Mile Island to Fukushima at Inference Archives in Brooklyn, New York. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

In 2012, my observation was that young people in Japan were galvanized onto the streets through the organizational efforts of existing civic society actors and a smaller number of new groups that emerged post-Fukushima, but failed to be drawn within a larger, more extensive movement. Nothing like the activist subculture which presently exists in Taiwan among young people formed. As such, people came out for one big day of protest, or several large days of protest and then went home. Nowhere was this most prominent in that an escalating action of large magnitude was planned against the Oi restarts, with individuals chaining themselves together to attempt to prevent the restart and vowing to remain there as long as possible. But where this had the potential to become something like the Sunflower Movement, or even Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement of recent memory, if the action had caught public attention, instead of prolonging the action as long as possible and seeking to galvanize the public through it, the action lasted for a weekend and then fizzled apart. So the 2012 anti-nuclear movement eventually collapsed and was unsuccessful in its demands.

Certainly, Japan no less than Taiwan has a culture of vibrant artistry in protest movements to form an attractive aesthetic for something like an activist subculture. It is true that Japan has not achieved the level of subcultural omnipresence in Taiwan whereby, say, almost every major Taiwanese independent musician, artist, and photographer is in public support of the anti-nuclear movement and every hipster coffee shop is plastered with anti-nuclear paraphernalia as the famed “Anti-Nuclear Flag”—or that one can walk through any subway train to discover several anti-nuclear activists in Taipei on the basis of the yellow ribbons attached to their belongings. But even if activist culture is less all-encompassing of society, one only need to point to the proliferation of Leftist bars and cafes in Tokyo, or the continual activity of the politically radical residents of Koenji, as compared to, for example, the relative sparsity of such institutions in Taipei to point to where Japanese activist culture is very much alive. Yet if part of the failure of Japan’s anti-nuclear movement is in its failure to attract young, enthusiastic activists to carry on organizing activity, that may have to do with entrenched sectarianism in activist politics and a reluctance to expand the purview of activist politics in order to appeal to fresh faces.

Taiwan has a longstanding history of student groups, NGOs, civil society organizations participating in politics coming out of the Martial Law era and the period of Taiwan’s democratic transition during the 90s. Similarly, Japan, has a rich variety of organizations involved in political activism, some of which whose existence dates back for decades, if not to the post-war itself. But the difference between Taiwanese and Japanese organization may be in some sense a matter of age, because Japanese organizations strike as more ossified, that is, less willing to shift course and change activity, as their energy is focused on the preservation of the same activity as it has been done for years. There, too, seems to be less space in Japan for new organizations, whether NGOs or political organizations, to form. The average age of members of Japanese activist groups does, as a result, seem that much older.

Namely, some Japanese activist or political organizations exist all the way back to the 1960s, where even if in Taiwan there are some organizations whose history lay in the Dangwai Movement of the 1970s, the currently activist organizations as a rule have much more contemporary foundation. It is very rare for an organization to exist for over several decades in Taiwan, by contrast. Where such organizations have been able to maintain there existence over long periods of time in Japan, it is because the old hands keep at it up until the present and pick up enough young people who are willing to subordinate themselves to older activists and continue the same activity for such organizations to survive.

Moreover, it seems to me that Taiwanese civil society organizations are generally more willing to cooperate and more porous in nature. When young people participate in politics, it is less through joining one specific organization and directing their activity solely towards the activities of that organization. By contrast, it seems that in some way, the channels for participation in Japanese activism is often done through an organization and, unfortunately, Japan’s existent political organizations are sometimes not up to the task. The long history of Japanese political organization sometimes makes them more sectarian in nature and unwilling to cooperate because of past bad blood. On the other hand, in Taiwan, activists of one organization are always participating in a variety of causes, everyone knows everyone, and there are less fights and internal splits that become paralyzing to or destructive of organization.

It may just be that Taiwanese activism exists in just a smaller world in which fights are more often avoided because of the much more severe ramifications of splits for activity, Taiwan being many times smaller than Japan. But the relative lack of sectarianism seems a strength of Taiwanese activism. Even if the other side of the coin may be that when disagreements do exist among Taiwanese activists, they are usually buried and effaced under the general consensus of civil society, it is easier for civil society as a whole to build consensus when the boundary between groups can be very fluid. Not only does this allows for experimentation in tactics and strategies, with cross-pollination between groups, allowing for the adaptation of new tactics and strategies aimed at appealing to the general public, and this allows civil society as a whole to appeal to those who previously were not activists. Participation in activism does not demand total commitment to any one group, for example.

The porous nature of participation and the attendant flexibility of civil society groups is probably what led to the incorporation of popular art into social movements in Taiwan on such a scale that every major artist of any sort at least makes some gesture towards social issues. In particular, the participation of artists in social movements is important because of the ability of artists to give movements a guiding aesthetic that can serve to attract general members of society. By contrast, I hear from acquaintances who are members of Japanese political organizations that older members of their respective organizations are enraged by something as simple the prospect of changing typography from decades old newspaper formats so as to look less out of step with the present.

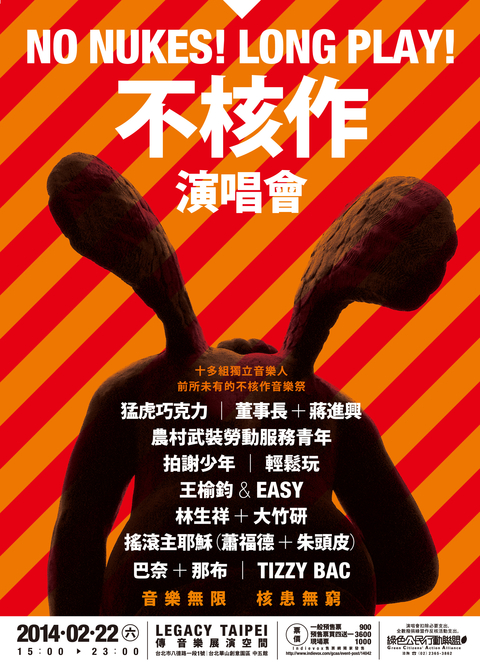

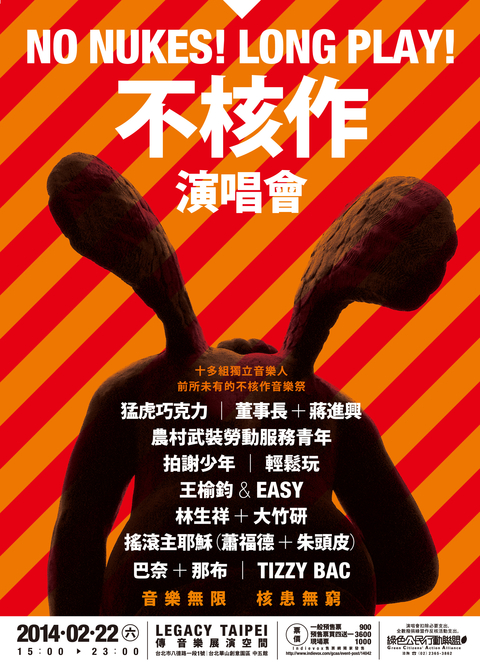

Poster for the No Nukes! Long Play!不核作演唱會 show organized by Green Citizens’ Action Alliance on February 22nd in Taipei. to promote the No Nukes! Long Play! album.

Poster for the No Nukes! Long Play!不核作演唱會 show organized by Green Citizens’ Action Alliance on February 22nd in Taipei. to promote the No Nukes! Long Play! album.

Artists’ participation in the Japanese anti-nuclear movement, of course, included such luminaries as Ryuichi Sakamoto, Yoshitomo Nara, and the emergence of new artists specifically oriented towards the nuclear issue as 281_Anti Nuke. These artists and others would put together a series of concerts, exhibitions, and the like concerning the issue of nuclear power. This, too, was the case in Taiwan, where established artists would put collaboratively use their artistic production to raise awareness of the nuclear issue, as probably best emblematized by the No Nukes! Long Play! 不核作 – 臺灣獨立音樂反核輯 album that was released over the summer, featuring artists as Tizzy Bac, Sorry Youth, Frande, the activist rappers of Community Service/Kou Chou Ching, and the photography of Chang Chao-Tang. But perhaps such artistic productions failed to be incorporated into activist politics on the level of organization in Japan, when established groups were too intent on waving the same banners that they had been waving for decades.

When a severe political crisis strikes, as in the Fukushima incident or the repeal of Article 9 or the passing of the CSSTA, people who have never been activists before are drawn out onto the streets. Whether they become activists from then on or just go back home is largely dependent on what channels exist for them to participate in politics. But when the threshold for participation is set too high, people fail to be brought in. Moreover, when activist politics strikes in a register far too removed from the immediacy of normal social experience, for non-activists activism does not present itself as an activity they might engage in in the future. It was much more difficult for regular members of society, or at least the young, to be brought into the Japanese anti-nuclear movement on a mass scale, as a result.

It is true that the differences in the Taiwanese political response and the Japanese political response to nuclear power may just reflect differences between Taiwanese and Japanese society. It may be that Taiwanese society is in some sense, more “politicized” than Japanese society, which allows for the incorporation of the public at large within social movements. After all, Taiwan faces existential threats to its constitution as a nation constantly from China, and the history of authoritarianism as well as the history of the resistance to authoritarian is still fairly recent. However, if just as the Sunflower Movement was society’s reaction to a crisis of a all-encompassing of society regarding the economic encroachment of China and the undemocratic rule of the KMT, so too should the post-Fukushima anti-nuclear movement have been for Japan as a crisis affecting of Japanese society.

Confrontation between protestors and the police on July 13th, 2012, in Kasumigaseki, Tokyo. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Confrontation between protestors and the police on July 13th, 2012, in Kasumigaseki, Tokyo. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

But, accordingly, what must also be learned from for Japan is how exactly in Taiwan, the anti-nuclear movement could grow to such strength when Taiwan has never suffered a disaster on par as Fukushima. Taiwan had no Fukushima that led to the resurgence of the anti-nuclear movement in the last two or three years. Taiwan’s Fukushima was Fukushima itself. It is hard to understand how if in Taipei 130,000 people could take the streets in Taipei to protest anti-nuclear power in the absence of catastrophic nuclear disaster, only 150,000 to 200,000 could take the streets in Tokyo after Fukushima in July 2012—much more so given Japan’s population is six times that of Taiwan and entire population of Taiwan is less than that of the Tokyo metropolitan area.

An International Issue

THE ISSUE OF nuclear power is not one that can be settled purely on a country-to-country basis. Radiation, after all, surmounts borders. Fukushima affected far more than just Japan. Nuclear power thus cannot be addressed as an issue on the basis of the nuclear issue in one country or another. This makes nuclear power a valuable case study for activist politics, so far as it is an issue which demands surmounting national borders in order to find resolution, just as the deeper problems of society are usually those which demand international resolutions. In the near future, with the construction of nuclear power plants in China, Taiwanese and Japanese activists will face the challenge of cooperating with Chinese activists despite the difficulties of surmounting the respective enmities between Taiwan and China or between Japan and China, pointing towards the means by which activism must transcend national ideology.

The “Windmill Chorus”, a singing group regularly a presence at anti-nuclear protests, performing at the “5-6 Movement” weekly protest at Liberty Plaza in Taipei on June 27th of this year. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

The “Windmill Chorus”, a singing group regularly a presence at anti-nuclear protests, performing at the “5-6 Movement” weekly protest at Liberty Plaza in Taipei on June 27th of this year. Photo credit: Brian Hioe

However, transnational cooperative endeavors to date have usually largely been along the lines of “solidarity”, in which activists of one country or another offer sympathy to the struggles of those in another country, but in which deeper, more fundamental cooperation is rarely broached. In fact, while activists in one country might learn from activists in other countries, too often, this also fails to be enough. Learning from one another can only go so far when the problem they are facing is larger than any individual country. What is needed is not simply just to learn from one another, and then take lessons learned back to one’s home country and apply them to one’s own activity, as is too often the case. Rather, shared problems on that scale demand transnational strategizing at an fundamental level. However, the networks and structures that allow for transnational political cooperation on the fundamental level of tactics, strategies, and aims do not currently exist in the present.

Attempts have been to establish transnational cooperative endeavors have taken place, for example, in attempts to coordinate the weekly anti-nuclear protests that take place outside of the Prime Minister’s Residence in Tokyo to the weekly anti-nuclear protests of the “5-6 Movement” which take place at Liberty Plaza in Taipei which failed because of the Chinese-Japanese language barrier. Even if one can also point towards prominent problems of hierarchy in the weekly protests in Tokyo, for example, or the sometimes overly moderate tone taken by the “5-6 Movement”, this may be a valuable, even unique, but missed opportunity. The interest of Japanese radical intellectual Karatani Kojin in the Sunflower Movement is also heartening, as is also stumbling across Taiwan’s ubiquitous “Anti-Nuclear Flag” in activist establishments as Nantoka Bar in Koenji, Tokyo over the past summer, so far as this is demonstrative of the interest of activists in each other’s activities across borders.

Yet too often this remains the politics of “solidarity” in which activists of one country offers its sympathies to the activists of another country. What is exchanged is at best a sense of shared cause. For the nuclear issue or other structural issues facing activists in East Asia, what will be needed is coordination of action at far deeper level than just empathetic solidarity.