by Garrett Dee

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Front Cover

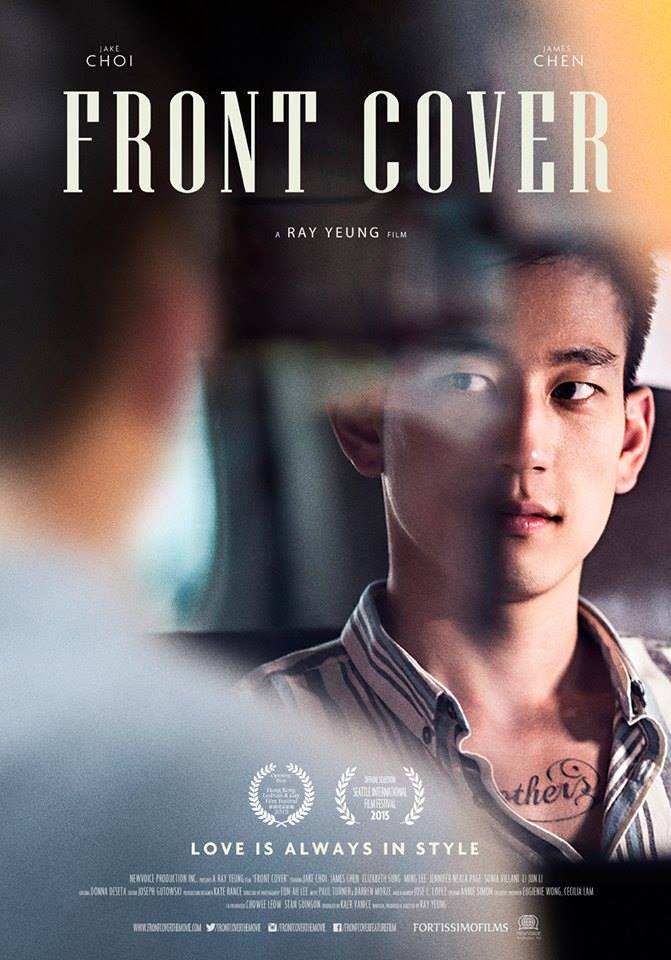

Front Cover is a film by Hong Kong director Ray Yeung which tells the story of a Chinese American stylist Ryan Fu (played by actor Jake Choi) and Beijing film star Ning (played by actor James Chen) who over the course of preparing for a major photo shoot develop a mutual attraction, forcing both of the men to confront their own buried feelings on race and sexuality at a personal cost. The following piece is based off of conversations New Bloom’s Garrett Dee had with the two lead actors about their experience making the film and the message they hope audiences will take away. The film will screen at the Taipei International Queer Film Festival on October 22 and 30, show times can be found here.

TWO ASIAN MEN falling in love may not be the first image that would pop into many audiences’ minds were they to think about the front cover of anything, but getting them to question why that’s not the case is exactly what the film Front Cover is hoping to do. Ahead of the film’s screening at the Taipei International Queer Film Festival, I spoke with director Ray Yeung and was able to learn more about his vision as well as the motivation behind this unique story. More recently, I had the opportunity to talk with lead actors Jake Choi, who plays Ryan, and James Chen, who plays Ning, about their views on race and sexual orientation in both Asia and the US, as well as their experiences in fleshing out these two characters and the message they hope audiences take away from the film.

Film poster

Film poster

Ironically, given the way their characters are portrayed in the film, one would think that it was Jake that was the more reserved one and James the more boisterous, but that was actually not the case. When I first spoke with James, I could almost immediately see that he was the kind of person that really put a lot of thought into being articulate. Jake, on the other hand, had a frank and expressive style that was refreshingly open; he wasn’t afraid to call out Hollywood studios on their blatant racism and at one point even referred to himself as having “beautiful Asian features”. However, despite his shoulder length hair and tattoos, Jake actually came off as quite humble during the conversation (when asked if he considered himself a sex symbol after this film, he laughed and said the audience will have to decide for themselves).

Though their style and manner of expressing themselves sets them apart at first glance, over the course of talking with both of them there was much commonality in the themes they were emphasizing, in particular the importance they placed upon doing justice to these two characters. For James in particular, this presented a challenge, as he was, as an American actor, stepping into the role of a person born and raised in Beijing. Accented Asian characters in American film fall into the realm of caricature more often than not, usually relegated to the category of aggressively asexual punchlines or flawless kung fu mystical types with almost nonexistent character development. James told me that he had spent time in China before and had watched a long list of Chinese cinema masterpieces, questioning deeply who this character was and where he comes from, as well what it would have been like to grow up in such an imposing country as China while having to live with a secret. Jake, too, drew upon his own life experiences growing up in an immigrant household as well as the experiences of gay people he had met during his three years working at a gay bar to make sure that Ryan’s onscreen struggle came across in a way that people would find something of themselves in.

After having spoken with director Ray Yeung about his own coming out and how much of this story was autobiographically rooted, I realized what a burden he had placed upon the lead actors in making both the characters and their relationship feel sincere. Both of the actors are straight, and yet when asked about how they went about preparing to fall in love with each other on screen, it was surprising to see how much of a non-issue it was to both of them. This might not have been the case as early as a decade ago, when many young heterosexual actors in the early stages of their career would have squirmed at the prospect of playing a gay character in an independent film. However, these two both really embraced their respective characters’ sexuality and spoke to me about how much of a priority it was for them to give gay audiences a portrayal of these two characters and their relationship that was authentic and respectful.

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

In fact, James spoke about one of Front Cover’s greatest strengths being the fact that it works meticulously to break down stereotypes on several fronts, one of them being the constant invalidation of Asian male masculinity in the media. He was especially proud that his character came across as quite authoritative, something that US audiences haven’t been accustomed to seeing in an Asian character. In his portrayal of Ning, he rooted the character in this idea of him being decidedly masculine, of not letting anyone push him around, and didn’t let the fact that the character was an Asian gay man affect that. This idea that being gay or being Asian doesn’t automatically equate to femininity if that’s not inherent to that person, that the intersection of these two identities is something that can inform a character without defining him, is one of the core messages of this film.

What was also important to them was the issue of making sure it was a fully authentic gay Asian story that had a message that pushed the boundaries of what audiences are used to seeing in film. This year has been particularly difficult as far as visibility for Asian Americans in the media, with Ghost in the Shell and Doctor Strange both giving roles originally conceived of as Asian to white actors, Marvel failing to rectify its yellowfacing of The Iron Fist, and most recently with the revelation that Disney had been flirting with the idea of giving Mulan a white male love interest in the live-action remake (an idea not unlike the shoehorning of Matt Damon into Chinese history in The Great Wall). After speaking with James and Jake, it was clear that they are both quite talented actors, but like many actors of Asian descent in the United States, they hadn’t had the chance to portray truly three-dimensional characters because of their ethnicity. In speaking about his role as Ning, James described having the chance to play a Chinese man with depth and character development as a dream come true and the realization of his goal as an actor, but at the same time expressed frustration with the lack of these type of roles in his career up until this point.

Both of these actors brought a lot of themselves of themselves into these characters and it was clear how much they connected with the experience of this story as well as with the the importance of getting people to understand what it means to be Asian American in the United States. The lack of visible Asian male role models in the media caused them both a lot of internal struggle growing up and trying to assimilate into a mostly white culture. James shared with me some of the experiences he had with being harassed when he was a kid because of his race, which, like he says, “Only needs to happen once and you never forget.”

Much like the character of Ryan Fu in the film, both Jake and James grew up as the children of immigrants to the United States: Jake’s parents were Korean immigrants to the United States and James is Chinese American, his mother being overseas Chinese and his father having lived in Taiwan following the takeover of the Chinese Communist Party before moving to the US. The immigrant experience was something that director Ray Yeung had spoken at length about being something he really wanted to emphasize in this film. Similar to the first-generation American characters in celebrated Chinese American author Gene Yuen Lang’s celebrated graphic novel American Born Chinese, Jake told me that he had spent much of his life up until he was in college running away from his parents’ culture and hating his race, something that caused a lot of conflict in his household with his more traditional Korean parents.

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

The insecurity of immigrant parents in the United States, especially those coming from Asia, is something that most Americans have little conception of. James bemoaned to me the frustration that his parents had not spent more time educating him and his sister in their language and culture, but this is the norm rather than the exception amongst many children of immigrant parents. The harmful stereotypes of the “model minority” and the “tiger mother” are oft accentuated in the media and derogatorily played up as inherent to Asian culture, but rarely is the harsh reality of being an immigrant parent raising children in a foreign country with an unfamiliar language analyzed in depth from a fair perspective. In a scene that often came up in conversation with the actors and the director, Ryan’s mother, played by actress Elizabeth Sung, has a heartfelt moment of acceptance with the deeply closeted Ning. This challenges the damaging stereotype that Asian households are devoid of affection and gives a peek into the internal conflict these parents have to endure. James spoke about his wish that gay Asian Americans would see come away from this film with the understanding that though it may be difficult for their parents to express their emotions, that their love for their children is always there.

As Jake mentioned during the conversation, Ryan never feeling at home in his native country just because of his face is something that Asian Americans actually deal with in real life on a constant basis but that most Americans may not be aware of. When a FOX News reporter like James Waters feels that it’s acceptable to walk into a predominantly Asian neighbor and start asking purposefully demeaning questions to the residents in order to get them to caricature themselves, it’s clear that the “perpetual foreigner” myth is alive and well. Many people don’t know that Chinese immigrants were the group excluded from entering the US the most recently, and many still won’t realize how much the model minority myth damages Asian American’s perception by the mainstream media or, as Jake and James both mention, their own perceptions of themselves.

When Jake spoke about the microaggressions he constantly receives mostly from white people which are at times so small that they go over his head, I was reminded of a scene visible in the Front Cover trailer in which Ryan’s boss, played by Sonia Villani, after assigning him to work with up and coming Beijing film star Ning, is shocked that Ryan has never heard of him before. This idea that even Asian Americans who were born in the United States are constantly living one foot in the US and one foot across the Pacific Ocean creates a notion that they aren’t truly American, that they have to prove that they don’t have a divided loyalty.

This kind of internal struggle being something that has defined the Asian American experience was something that resonated strongly with both of the lead actors. On one hand, it seems that being accepted in American society as a person of Asian descent is challenging to the point of impossibility unless there are changes in today’s social and political climate. For the most part, American society still refuses to acknowledge the existence of the Asian American community in public life, and if it does at all, it is only as the butt of a joke, as evidenced by this year’s debacle at the Oscars in which young Asian American kids were unwittingly used as props for some distasteful humor about child labor.

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

Film still. Photo credit: Front Cover

On the other hand, the experience of discrimination and the struggle to find representation in your own society as an Asian American in the United States is something that both Jake and James told me that audiences in Asia may have trouble comprehending, and something they hope to convey through the film’s screenings here. Both actors had spent some time living in Asia in the past, and both praised the reception the film has had during its respective screenings in Hong Kong and Bangkok. However, Jake lamented the fact that audiences in Asia may not be able to empathize with Asian American outrage over things like whitewashing and misrepresentation, as Asians in Asia enjoy full representation in the media (James compared it to being white in the US). This notion of Asian Americans living in this kind of shameful no man’s land rejected by both their country of birth and their country of heritage shows up in Ryan’s contrast with Ning, whose bravado and presence comes as a result of his complete ease in his own culture, whereas Ryan has spent his life shunning anything remotely Asian and yet never feeling fully accepted by a predominately white society.

The film’s hallmark lies in the fact that every person significantly involved with its production has repeatedly professed their desire to challenge the prevailing notions on race and sexuality and portray gay Asian men as fully realized characters with their own courage and flaws. Just the fact that both main characters in this film are Asian men and that the only role white supporting actors serve is as background to the story is revolutionary enough in itself, and even more so to have two actors who have internalized the films’ message and have such a perspective on their own roles in a larger struggle for justice. Both of them expressed to me their desire to continue to play these kinds of characters either in the United States or in Asia. Let’s hope that we see more not just of these two but of more films like this one.