by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

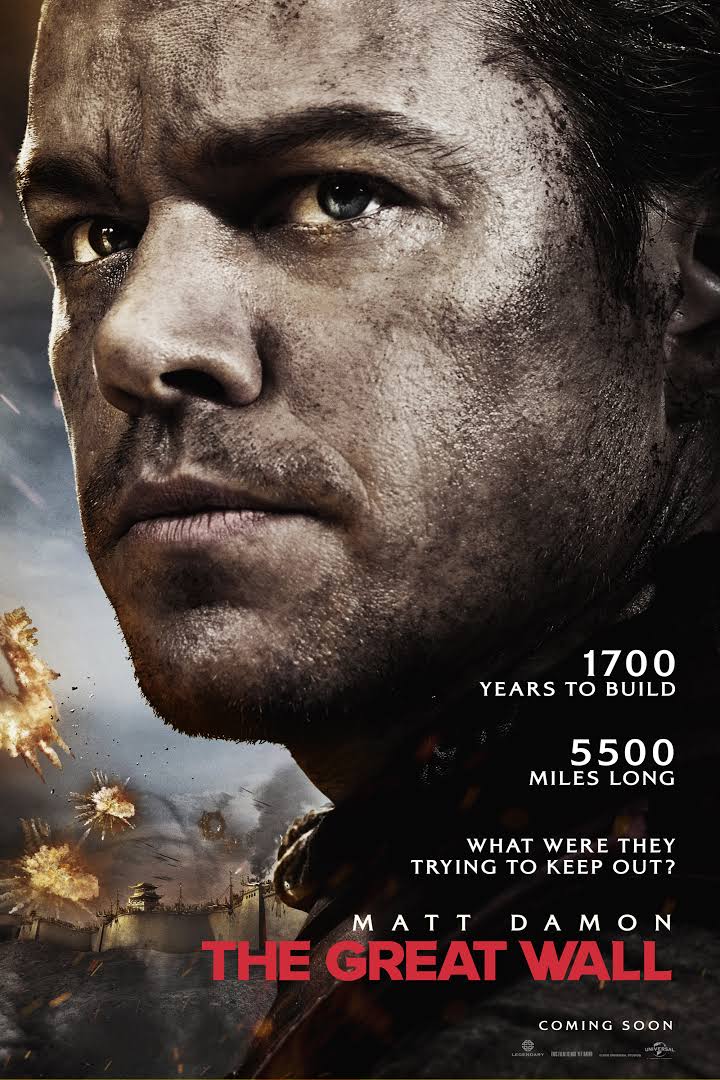

Photo credit: The Great Wall

Asian-Americans Failing To Take Into Account The Possibility Of Asians Whitewashing Asians

RECENT BACKLASH by Asian-Americans against The Great Wall, starring Matt Damon, for “whitewashing” Asians from a movie ostensibly set in China, have unfortunately generally missed the point. The movie is seen as continuing the Hollywood trend of removing Asians from visible roles and replacing them with white actors, for example, through the casting of Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One in Doctor Strange, casting a white actor in the role of a Tibetan character or the casting of Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell, despite that the character should be Japanese.

Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi (left) and Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One (right). Particularly provoking of outrage was the revelation that producers of Ghost in the Shell had explored ways to make Johansson look more Asian and that a Tibetan actor was not cast in the role of the Ancient One likely to avoid offending China. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell and Doctor Strange

Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi (left) and Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One (right). Particularly provoking of outrage was the revelation that producers of Ghost in the Shell had explored ways to make Johansson look more Asian and that a Tibetan actor was not cast in the role of the Ancient One likely to avoid offending China. Photo credit: Ghost in the Shell and Doctor Strange

This is certainly a problem in Hollywood. Outrage in such cases is well deserved. But The Great Wall is not just another Hollywood production. What Asian-Americans have not been sufficiently attentive to is that the film is a American-Chinese coproduction. As such, this is actually not a case of presumably mostly white Hollywood executives whitewashing Asians, but more probably of Asians whitewashing themselves. As Chinese language media has pointed out, it seems far more likely that it was the Chinese investors in the film who decided to feature a white protagonist. Indeed, in consideration of the film being a coproduction between China and America, some have even sought to absolve Chinese investors in the film from guilt, apparently in the belief that white people are the only ones capable of whitewashing and this whitewashing comes from the Hollywood executives working on The Great Wall. The truth is hardly so simple.

Attempts By China, As A Rising Superpower, To Produce A Global Blockbuster—Featuring White People

SUCH “WHITEWASHING” in The Great Wall is more likely not to be coming from Hollywood producers, but likely from the Chinese producers themselves. In many cases, despite being billed as American-Chinese coproductions—presumably in hopes that this branding will allow Chinese films to circulate on the global market—sometimes the Chinese role in coproduction is quite evidently larger than the American role, or the so-called American role is actually Chinese in nature. The Great Wall, for instance, is produced by Legendary, which though seeming to be an American company based out of America, is actually owned by the Chinese Wanda Group. Indeed, The Great Wall will be the most expensive Chinese film ever made, with a budget of $135 million USD.

The Great Wall, directed by Zhang Yimou, comes out of a recent trend of high budget coproductions between Hollywood and China, usually featuring both Chinese and American stars. Other examples would be 2015 film Dragon Blade, featuring Jackie Chan, John Cusack, and Adrian Brody, and 2014 film Outcast, featuring Hayden Christiansen and Nicolas Cage.

The rise of this trend of film is directly tied to the economic and political rise of China as a superpower. In order to assert itself as having achieved a status of parity with America, the world’s other superpower, much as the prominence of Hollywood film internationally is an expression of American power, China wishes to have a global blockbuster. What better way to do this, then, but to create a blockbuster which in some way reflects “traditional” Chinese culture but features Hollywood stars, this in order to attract a western audiences?

Film poster for Dragon Blade. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

Film poster for Dragon Blade. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

We might note the similarity between The Great Wall, Dragon Blade, and Outcast in that they are all set in ancient times and thus spotlight ancient China—but that the western stars of these movies are in fact given more prominence than Chinese actors, even when the film is set in China. Notably, though many of the plot details of The Great Wall are still unknown, many of these films feature the “ancient” West coming into contact with “ancient” China with Dragon Blade revolving around Roman legionnaires coming into contact with Han dynasty China and Outcast featuring Nicolas Cage as a crusader in Song dynasty China.

Indeed, though the plot details of what Matt Damon’s role in The Great Wall is as a white man somehow living in China during the Song dynasty have yet to be explained, the plot of Outcast similarly features Chinese individuals who must be saved by Nicolas Cage, as heroic white protagonist of this film who is a drifter that ends up in China from medieval Europe. While Dragon Blade features Jackie Chan in a prominent role, Chan is notably the exception to the rule as a Chinese actor who has made it in the West.

American-Chinese Co-Productions As Propaganda Productions Of Chinese State Ideology?

WITH THIS NEW trend of coproductions between Hollywood and China, even when these are largely private productions, one must also point to the role of the Chinese state. The Chinese state is heavily involved in the Chinese film industry and ostensibly private film companies sometimes need strong connections with the state in order to operate. This can extend as far as American Chinese-owned companies. The state likely also comes to influence the content of films, even if production companies are privately owned.

DMG Entertainment, for example, which was involved in producing Looper and Transcendence, also produced the nationalist film The Founding of A Republic to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China—something it did in cooperation with the state-owned China Film Group Corporation, which also be distributing The Great Wall when it is released in China. DMG Entertainment has also been accused of operating on behalf of China to try and silence critical voices of the Chinese government’s human rights abuses, for example, in seeking to buy up Taiwanese television networks in order to influence their reporting.

Zhang Yimou. Photo credit: China Daily

Zhang Yimou. Photo credit: China Daily

Indeed, in the case of recent big budget Chinese and American co-productions, one finds that many of the Chinese staff members are noted as apologists for the Chinese state. In the case of The Great Wall, director Zhang Yimou is a noted apologist for the Chinese government. Having begun his career as a director hailed as an auteur who was quite critical of the Chinese government, Zhang’s eventual accommodation to the state can be seen through his directing the opening and closing ceremonies for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Zhang also turned towards making big-budget films with a western target audience which seem to inflect the political agenda of the Chinese state after his 2002 film Hero became a commercial success in the West—a film who’s plot often read as justifying authoritarian measures by government in order to preserve social order, including mass murder or forcible conquest.

Jackie Chan’s starring in Dragon Blade is also along these lines, given Chan’s often acting as an apologist for the Chinese government, and having directly expressed condescension towards western democratic values, suggesting that China needs some measure of authoritarianism. The plot of Dragon Blade suggests that the West must step down from its position of global authority in order to allow China to be the new international power that polices the world, presumably with the veiled suggestion that America should allow China to take over its current role as world policeman—Chan acting in the film as the representative of China.

Even if there is not direct involvement of the Chinese government, which is also possible, such films nonetheless express Chinese state ideology. But this backdrop, regardless, is what Asian-Americans have missed in accusing The Great Wall of whitewashing. Yet even apart from failing to grasp the political background of contemporary Chinese film representations, if Asian-Americans have failed to grasp this larger cultural context, should it really be surprising that Asians would feature white actors in their films as white saviors? This is the broader social problem that Asian-Americans have failed to understand in projecting race relations in America onto Asia.

The Failure of Asian-Americans to Grasp Race Relations in Asia: White People as a Status Marker for Asians

WITH THE POLITICAL and economic rise of China, it becomes that association with white people are a sign of status for many Chinese—that is, a sign of global cosmopolitanism as tied to economic power. There even exists services to rent out white people to attend social events in China, again, as a sign of success. Apart from that using white actors in Chinese films is in part to allow such films access to the global market, it also serves to show off China’s economic success if Hollywood stars can be hired to act in Chinese films. Could one imagine Matt Damon be hired to act in a Bollywood production, for example? On the other hand, now it is possible for Hollywood big names to be hired to star in Chinese films. Such are racial dynamics between Asians and whites in Asia—not America. Notably, the response to The Great Wall in China has been quite different than that in America, with there not being much outrage in particular over featuring Matt Damon in the film and some even praising that fact. This would not be the first time that Asians themselves have reacted very differently from Asian-Americans when it comes to accusations of cultural appropriation.

But it really should not be so surprising to Asian-Americans that Asians can whitewash themselves, and if they project this concern onto The Great Wall, this is projecting race relations in America onto Asia. Sometimes this also ultimately returns to that Asian-Americans sometimes do not actually understand Asia very well. Despite thinking that their background allows them to understand Asia better than white people, sometimes Asia in fact serves as a blank canvas for Asian-Americans’ projected hopes, desires, and fears—in a manner which is not so different what westerners do and actually more American than anything else. Perhaps this can itself be seen as a form of internal Orientalism, in some sense. Asian-Americans, after all, hardly have some essential connection to Asia which allows them to inherently understand Asia by virtue of their background. This is what is ridiculous in attempts to claim that only white Hollywood investors would be capable of whitewashing, with the view that white people are capable of the act and Asian people incapable of it. And this is, in fact, to fail to understand a very real social problem.

Film poster for The Great Wall. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Film poster for The Great Wall. Photo credit: The Great Wall

Ultimately, what this returns to is the contradictions of Chinese nationalism in the present—between a China which wants to assert itself as a global force on par with America and western powers, but also retains a persistent sense of inferiority to the western world—wanting to claim that it is different from the West and better for that difference, but also wanting to prove to the West in its own terms that China has finally made it. These would be the contradictions of a rising superpower. And the trend of co-produced American-Chinese big budget films is an economic and cultural expression of this fact in the present. In this case, however, Asian-Americans would do well to know a bit more about Asia itself if they are to rail against cultural appropriation from Asian culture.