by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: See You Tomorrow

IT IS OF interest to note the Chinese government’s recent efforts to use film as a form of international soft power. As such, recent Chinese efforts aimed at breaking into the international market have sometimes taken the form of America-China co-productions, aimed at allowing Chinese films international circulation. This has at times led China to “whitewash” what are actually Chinese films by featuring white actors in roles which should go to Chinese actors.

But these films have not been successful, leading the Chinese government to try and stifle online criticisms of these film from within China, for fear that internal criticism damages the ability of these films to capture an international audience. Likewise, the fact that domestic moviegoers sometimes prefer western films is something that the Chinese government cannot condone, seeing as this undermines its attempt to exert soft power abroad through Chinese film.

Obviously, if the Chinese government wishes for Chinese films to circulate internationally, China simply needs to produce better films, which not only an international audience, but first a Chinese audience at home, will find enjoyable. In general, little will be accomplished from trying to curb domestic film criticism in attempts to make mediocre films into international hits. Indeed, if Chinese filmgoers do not find Chinese films interesting, who will? Perhaps China is best served by focusing on its domestic film audience and seeing what is popular among Chinese filmgoers before throwing vast amounts of money into films that neither Chinese nor international audiences enjoy.

Film poster for The Great Wall. Photo credit: The Great wall

Film poster for The Great Wall. Photo credit: The Great wall

Asian films remain peripheral when, as the Chinese government correctly claims, international film production is still dominated by western film production. Asian films which do manage to break out into the international sphere, inclusive of Chinese film, have become hits not because of their successful miming of Hollywood tropes but because of the particularities they embody of the national film industries that they emerge from. Examples include the fifth generation Chinese filmmakers, the Korean New Wave, and post-war Japanese cinema. To date, these are mostly art films which make it on the film festival circuit, then become more widely known among viewers of art house film, and there are few examples of non-western popular films which become widely known internationally.

An uneven situation persists between Asian films and global film production which remains dominated by western film. But successful Asian films which make it on the art film circuit or otherwise as break-out genre hits, as in the rising popularity of Korean horror films, nonetheless come to serve as a form of soft power for the countries that produce them. The rise of Japanese or Korean cinema to international attention likely returns to the global rise of the Japanese and Korean market economies, as a natural consequence of economic growth, and the rising importance of Japan and Korea in the world.

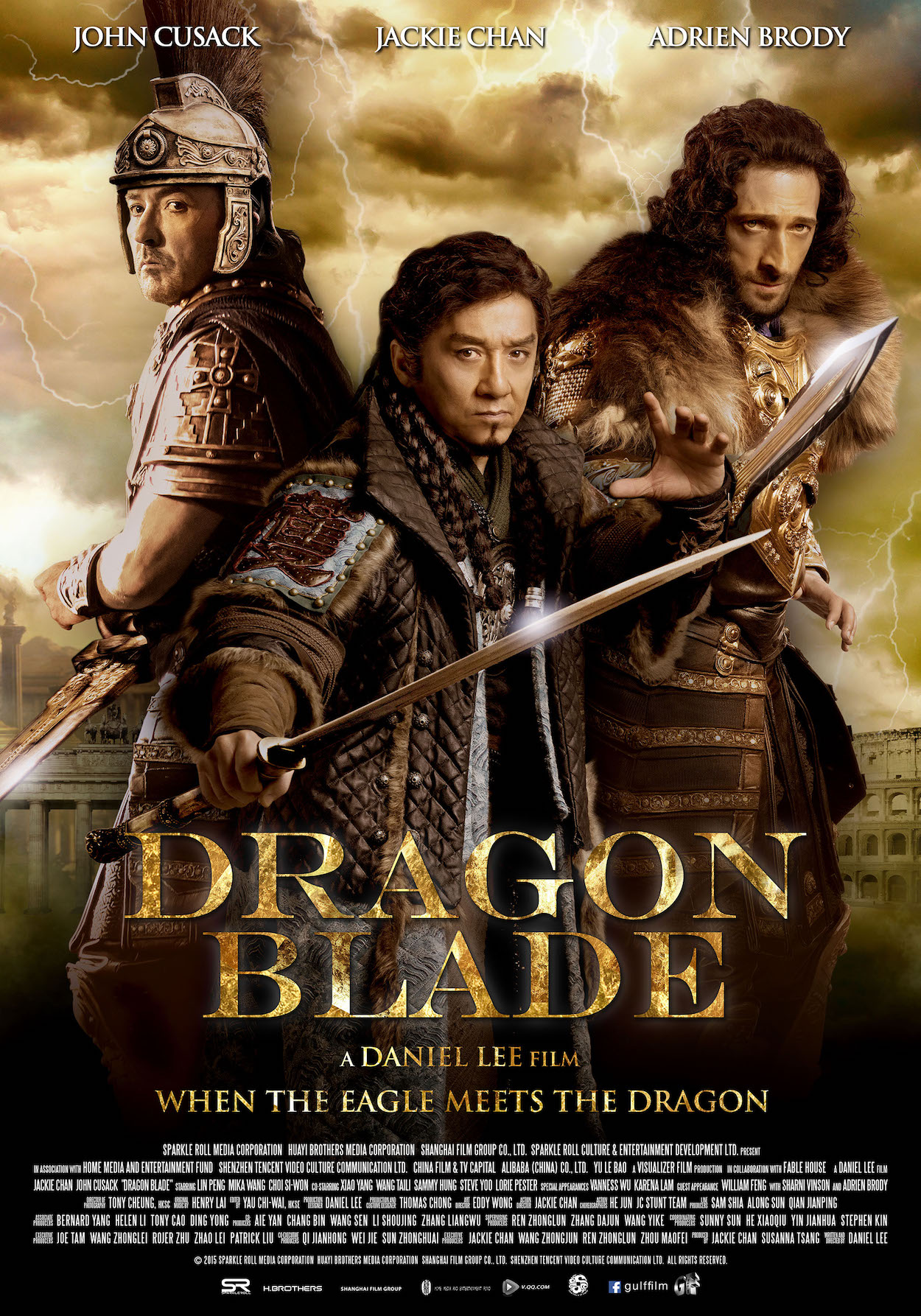

While the Japanese and Korean governments likely do aim to subsidize domestic film production keeping soft cultural power in mind, successful Japanese or Korean films were not “engineered” by either government. Similarly, although there is growing a trend of Asian art films which do seem produced with western arthouse audiences in mind, for example, particularly with the presence of self-Orientalizing elements in film, this is not as heavy-handed as attempts to appeal to western audiences in recent Chinese film such as The Great Wall, Dragon Blade, or Outcast through the prominent featuring of white actors.

Film poster for Dragon Blade. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

Film poster for Dragon Blade. Photo credit: Dragon Blade

In similar vein, we may note that Hollywood film production did not deliberately aim to become international in nature. Hollywood’s filmic tropes were derived solely with an American audience in mind. Yet with America’s international political and economic influence, Hollywood came to achieve global hegemony and occupy a large place in the global cinematic vernacular.

One imagines that with China’s rising place in the world, this would also occur as a natural of consequence with Chinese film—if only Chinese film, perhaps created with only a domestic audience in mind, was of sufficiently consistent quality. But given China’s current focus on big budget blockbusters that are mimetic of Hollywood film while having sharp Chinese nationalistic undertones, one can wholly imagine that even if the Chinese economy were to unambiguously surpass the American economy, Hollywood would remain hegemonic of global film.

Perhaps this all returns to the Chinese state’s attempt to manufacture successful film. Cinema is in some sense a highly democratic form of art, seeing as film production requires large amounts of cooperation between individuals, and film watching is a form of collective participation. The dominance of large corporations over film production in western countries is reflective, however, of how under capitalism, democracy is constrained by bourgeois rule. Similarly, under conditions of state capitalism in China, Chinese filmmaking is dominated by large production companies that work closely with the state, and the influence of the state itself.

Film poster for See You Tomorrow. Photo credit: See You Tomorrow

Film poster for See You Tomorrow. Photo credit: See You Tomorrow

But the potentials of Chinese film, both art house and popular in nature, are constrained by the heavy-handed attempts of the Chinese government to use Chinese film as a form of soft power abroad. Under such conditions, Chinese cinema is not allowed to realize itself. This snuffs out the potentials of Chinese film, by putting the clamp down on anything which would truly be unique to Chinese film and allow it global circulation as a distinctive form of film, in favor of what the authorities hope to be manufactured hits through a combination of miming Hollywood tropes injected with a heavy dose of Chinese nationalism. In line with its dismissal of democracy, Chinese government may simply not get that what makes films become internationally is oftentimes their originality, as emergent from the collaborative production processes of film and returning to the nature of film as a democratic form of art.

And so, it may be some time yet before China can produce a popular film which will make it big internationally. Again, this may return to the contradictions of contemporary Chinese nationalism, caught between the conflicting urges to find acceptance by the western world while also asserting that it is different from the western world, or even superior to it.