Reflections on Chinese and American State Relations in a Time of Rising Sino-American Tensions

by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Xinhua/Ju Peng

What Will Xi’s Visit to America Entail?

SEVERAL WEEKS after the largest military parade Asia has seen in probably decades put on by China in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Sino-Japanese War, Xi Jinping will arrive in America for a weeklong visit starting on September 22nd. Xi’s first visit to America in his capacity as Chinese president occurs in a time of increasing tensions between world superpowers America and China and increasing tensions in the Asia-Pacific as a product of anxiety about the growing threat of China’s military.

Indeed, despite that Xi’s visit to America had been long anticipated, as a result of American sanctions against Chinese companies regarding cyber attacks and cyber theft of American intellectual property, it had been a question as to whether the visit would be cancelled. It only became clear in mid-September that the event would, in fact, be happening.

But while Xi’s intentions ahead of his state visit have largely already been telegraphed, China’s actions as of late have generally presented obfuscating, oftentimes directly conflicting messages to the world. As China, all too aware of global anxiety over it’s economic, political, and military rise, has sought to allay fears by claiming that its rise will be peaceful in nature.

Xi at the military parade commemorating the 70th anniversary og the Sino-Japanese War held earlier this month. Photo credit: Landov/Xinhua/Barcroft Media

Xi at the military parade commemorating the 70th anniversary og the Sino-Japanese War held earlier this month. Photo credit: Landov/Xinhua/Barcroft Media

However, at the same time, even as China preaches peace, China seems compelled to assert its military strength and demonstrate that China is a military power which will not be bullied by western powers. And if apologists for China have sought to point to uneven relations of power between China and America, even if it may be true that the current global hegemon is and remains America, China’s aggressive foreign policy moves as of late would seem to be the proof to the contrary.

It is not merely enough to claim that Xi’s promises of peace are false. Rather, it would be that the Chinese state seems inexorably, even vaguely irrationally compelled to carry out contradictory actions in the domain of foreign affairs. Thus, it maybe something in the nature of the Chinese state apparatus itself which is the origin of such behavior. Perhaps there is something to claims about the inherent contradictions deeply riven into the Chinese state.

The Taiwan Question as an Example of China’s Contradictory Foreign Policy

IF A CENTRAL issue of Xi’s visit to Washington will no doubt be the so-called “Taiwan question,” actually it is that China’s Taiwan policy is another case in point of China’s contradictory foreign policy. Namely, China’s foreign policy is “contradictory” in regards to an apparent inability to read the atmosphere of relations in the Asia-Pacific and respond accordingly. Because although China lacks no less in regards to information gathering capacities as compared to any other state, China sometimes seems to be pathologically lacking the finesse required for delicate foreign policy—which is, in fact, quite often self-defeating in nature.

It is funny to note, for example, in the present that Chinese media would bill Hung Hsiu-Chu as Taiwan’s last hope for salvation against the perils of Tsai-Ing Wen. After the Sunflower Movement erupted in spring of 2014 as the largest social movement in Taiwan since the end of martial law in Taiwan, it is noteworthy that China seemed to take hands off approach to Taiwan, recognizing that its Taiwan policy had gone disastrously wrong at some point and that it would need to rethink its approach to Taiwan, backing off a planned visit by Taiwan Affairs Office Zhang Zhijun in April. Experts at that time prognosticated that China’s policies of moderation towards Taiwan as beginning under Hu Jintao would continue. After all, it was that the predecessor movement to the Sunflower Movement, the 2008 Wild Strawberry Movement which was the progenitor of many of the student networks which developed into the Sunflower Movement, was provoked by Zhang Zhijun’s visit to Taiwan in 2008.

Nevertheless, in the present, with the high possibility of a DPP victory under Tsai Ing-Wen—who against the international stereotype for the DPP set by Chen Shui-Bian would probably carry out a moderate foreign policy for Taiwan—China is stepping up aggressive moves aimed at intimidating Taiwan. For example, a recent set of live fire exercises by the Taiwanese navy in the Taiwan Strait would thus provoke China to announce its own set of live fire drills in the Taiwan Strait.

Hung Hsiu-Chu. Photo credit: 翻攝自網路

Hung Hsiu-Chu. Photo credit: 翻攝自網路

And if it has been that DPP presidential candidate Tsai Ing-Wen’s foreign policy have generally been aimed precisely at avoiding the aggression of cross-strait tensions, even if is probable that China realizes this on some level, it is that China is compelled to respond aggressively. As a result, even if when last year during the Sunflower Movement it actually seemed that China had grasped that its Taiwan policy and attempts to win over Taiwan had been going disastrously wrong, it is that in the present China warns against the dangerous of Tsai Ing-Wen’s independence rhetoric as potentially upsetting to cross-strait stability—never mind that there is no such rhetoric coming from Tsai Ing-Wen.

It would seem to be that China is unable to grasp that the DPP of the present has strayed quite far from its roots in the Taiwanese independence movement. Or more precisely, it is that even if elements of the Chinese state attentive to Taiwanese affairs realize that Tsai Ing-Wen’s DPP will more or less drift towards preserving the illusory “1992 Consensus,” the overall response of the Chinese is to come to hard upon Tsai as though Tsai were, in fact, advocating a hardline Taiwanese independence position. In consideration of the fact that China’s information gathering capacities vis-a-vis Taiwan cannot be inconsiderable, this is actually a surprise. But we can perhaps point towards the inability of China to grasp the realities of Taiwanese politics on an ideological level. Hence the grotesque overreaction of China in regards to the specter of Taiwanese independence ideology even when, for better or worse, there is hardly the need.

China’s Rise in the Shadow of America

WHERE XI’S VISIT to the US seem contradictory it is because that Xi’s visit seems to be aimed at reassuring the world of China’s peaceful rise and of reassuring the international community that China’s rise would not be threatening of the world order. But China’s actions as of late have been altogether too provocative of that world order.

What China would seek to reassure the US of is that its apparent recent attempts at displacing the US-centered world order which exists at present through its Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and its initiatives of the New Silk Road and One Belt, One Road. Actually such initiatives are broadly aimed at realizing a position of global power for China in the mold of America, much as America achieved its position of global hegemony in the past through forcing policies of global neoliberalism upon the world in the past.

In part, this is one reason for why China’s attempts to reassure the world its rise will be peaceful runs into certain contradictions from the get-go. But if the current world hegemon is America and the world accepts American hegemony as “peaceful,” what with the military interventions which America has conducted in the last fifteen years, then why should the world not also accept China’s rise as “peaceful”? China would seem to be plagued by the dilemma of that that its “rise” happens necessarily in the shadow of American dominance. One can more broadly point to that China lives in America’s shadow, for example, through the “Chinese Dream” as phrased in terms quite directly derived from the “American Dream” or the adaptation of terrorism discourse largely drawn from post-9/11 America against Islamic Uighur separatism in the past decade and a half.

It is actually quite true that China will be regarded as a dangerous and unstable by the international community for actions which are not so different from what America has done in the past—this by virtue of that American hegemony has become accepted by the world as the status quo. So if China insists on its peaceful rise while carrying out actions that are in fact quite disruptive to regional stability in the Asia-Pacific, this is one reason.

Contradictory Foreign Policy as Dictated by the Contradictions of Nationalism?

YET ON A deeper level we can also point to the contradictions riven in the nationalist frame by which the Chinese state responds to the world. Actually, it is not that the Chinese state is irrationally compelled to act it does by virtue of any irrationality particular to it, per se. If China has a tendency to respond in an overhanded manner to perceived threats, regardless of whether they are threats or not, or to insist upon on actions that conflict entirely with its rhetoric, this is because of that China is compelled to respond through a nationalist frame to possible threats.

To return to the example of Taiwanese independence rhetoric, despite the fact that China’s intelligence gathering apparatus is probably altogether too aware that Tsai Ing-Wen’s DPP has strayed quite far from the DPP’s roots in the Taiwanese independence movement, China is compelled to act as though the DPP were wholeheartedly in support of Taiwanese independence. That is to say, the Chinese state is compelled to react to threats as though they belong to either one of two categories: friend or enemy. The Chinese state sometimes seems as though it has no ability to define any gradation between these two categories. Indeed, it is such that many have called attention to the importance of Carl Schmitt’s “friend-enemy distinction” for understanding Chinese nationalism. Hence can we understand such displays as the passive-aggressiveness of, say, China’s vowing that its rise would be peaceful while simultaneously holding the largest military parade it has held in decades, as we saw earlier this.

Nonetheless, if American justification of its foreign policy occurs in the name of freedom and democracy—as going back to the Cold War in which this discourse arose to justify foreign policy actions in the name of democracy and as aimed at countering the influence of the undemocratic, godless communist Soviet Union—this is actually a form of American nationalist ideology which acts as apologist for the state’s actions. However, this ideology does not act on the state from outside, but is immanent to and serves as the language by which foreign policy actions are deliberated within the state apparatus itself. It is in this way that ideology comes to have an influence on the deliberations and actions of the state.

After all, if America justifies its foreign policy actions in the name of freedom and democracy, when one examines the internal documents by which foreign policy is discussed and decided, it is that one finds that these apparent ideological abstractions actually provide the concrete terms under which foreign policy decisions are thought through. [1] Because perhaps it is that all state apparatuses have nationalist ideology as the synthesizing glue which hold the vastness of the state bureaucracy together.

And as such, it is such that the actions of state apparatuses sometimes seem contradictory in and of themselves. Looking back at the history of American military intervention going back to the Cold War to the present, one often finds that American military intervention usually accomplishes the precise opposite of what was intended by destabilizing situations in which military intervention was meant to bring about stability—yet military intervention continues to happen nonetheless, as though by compulsion.

Since the Cold War, it is probably true that American actions aimed at installing regimes amenable to American interests to it have more often than not backfired, with the result being that American intervention leads to blowback against America and escalating existing tensions. Actually, it is that even where accusations follow against America for conducting military interventions for the sake of resource extraction, i.e., imperialism, it is sometimes it is that America sometimes does not actually accomplish much in terms of resource extraction. Rather, America ends up destabilizing the resource-rich regions in which it might be expected that America could extract resources—and it does this, over and over, institutional memory apparently being too weak to prevent repeating the mistakes of the past.

But whether America or China, more broadly, we can perhaps point towards a compulsive and self-undermining aspect to the behavior of states, as dictated by the nationalist ideology of that state, and the contradictions which are a part of any nationalist ideology. It would seem that China shares such a compulsion to undercutting itself. That would be China’s apparent inability to conduct foreign policy with finesse. In situations in which more delicately handled foreign policy might be useful, China comes in instead with a sledgehammer, as in when China is unable to modulate the contradictory messages it puts out or when China’s foreign policy actions would seem to be formulated precisely the opposite of what better instincts would advice.

And if with the rise of territorial tensions in the Asia-Pacific, the potential for the outbreak of conflict in the Asia-Pacific is on the rise, this proves dangerous. Because the apparent contradictions which lie in China’s nationalist ideology lay in its desire to assert the avenging of national humiliation while asserting the preordained supremacy of China. Thus, China continues to claim its ascent as aimed towards peaceful coexistence with other national powers, while also carrying out actions aimed at securing a position of global dominance which only undermine this claim. As it would be with any other state, Chinese nationalism is reflected in the actions of the Chinese state. However, China and America are no mere nation-states but world powers whose influence is global in nature. This is where they both are significant—and also dangerous.

Implications of Sino-American Relations For The Future of Asia

XI’S VISIT TO Washington hardly comes as the rapprochement of conflict between China and America, in the way of, for example, Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. Rather, Xi’s visit to Washington will probably be an occasion for Xi and Obama to negotiate existing tensions between America and China. It seems very unlikely that there will be any settlement over longstanding issues as the Taiwan question, Chinese cyberattacks conducted upon America, the American Rebalance To Asia, or the recent fluctuations of the Chinese stock market and what that might mean for American companies.

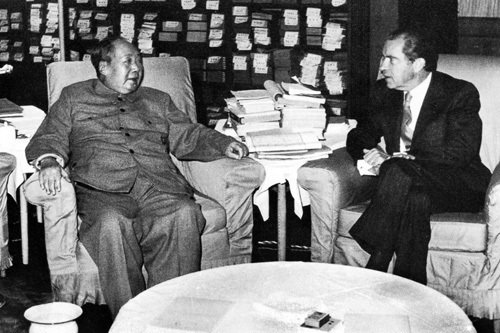

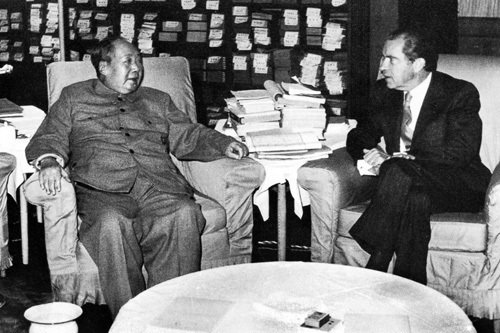

Nixon meeting Mao in 1972

Nixon meeting Mao in 1972

But what Xi’s visit to Washington should instead provoke reevaluation of the nature of the Chinese state—and of its parallels to the American state. Because going forward in world affairs, it will be the actions of these two nation-states which are determining of the future of the Asian-Pacific nation-states which are caught in between the two. And thus it may be of tantamount importance in the present to understand the course of the Asia-Pacific as it will be dictated by the interactions of the American state and Chinese state, when neither state behaves in a fully rational manner, and the decision-making processes of both both may be occluded by nationalist ideology as it is embedded within the state.

[1] For further reading, see James Peck’s Washington’s China

James Peck. Washington’s China: The National Security World, the Cold War, and the Origins of Globalism. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006.