by Will Leung

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Chan Sai Ho

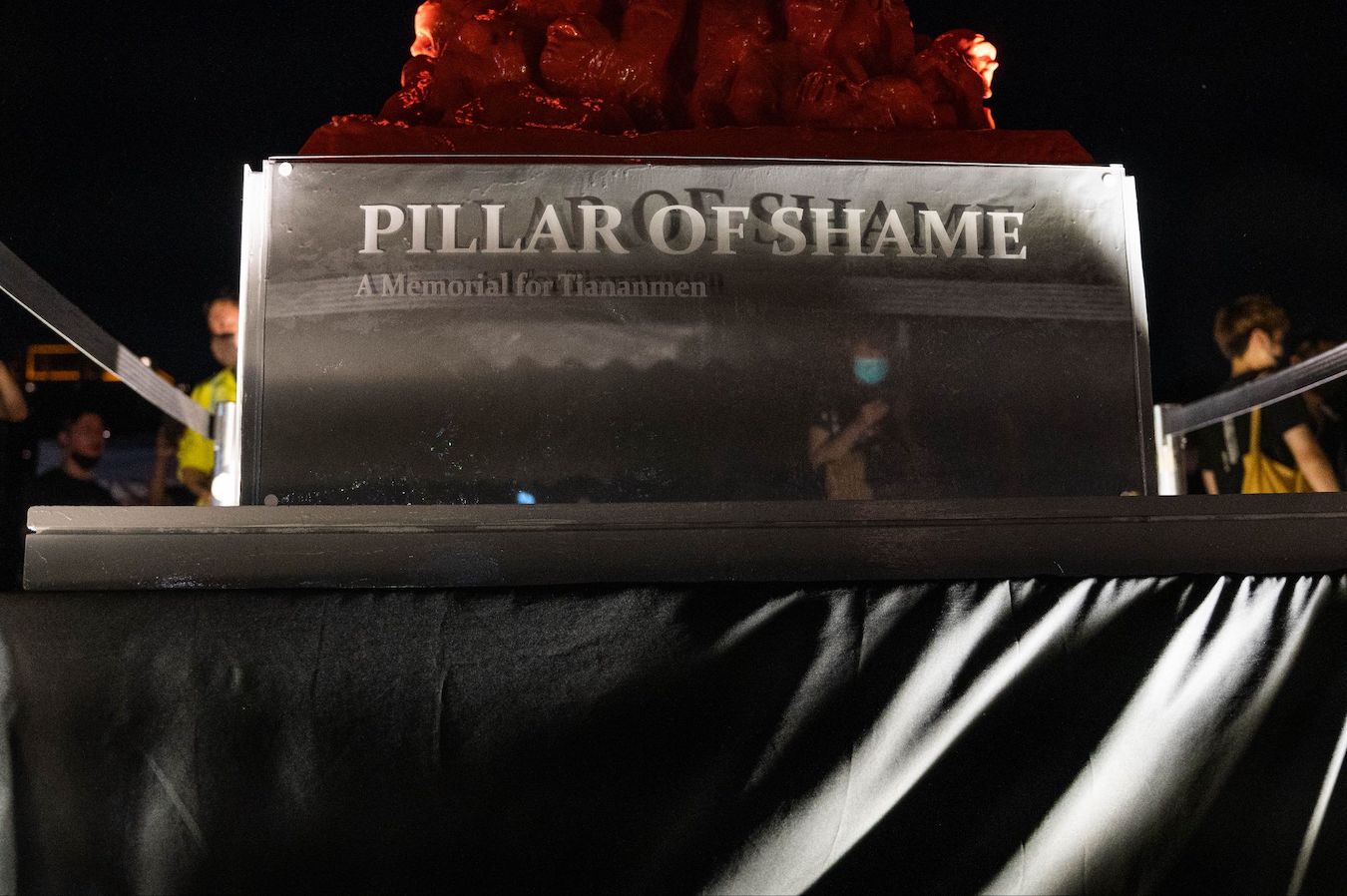

ON DECEMBER 25TH, 2021, just two days after the University of Hong Kong (HKU) plastic-wrapped and removed the Pillar of Shame from its campus, Taiwan’s New School For Democracy (華人民主書院) held a press conference at the Legislative Yuan in response to the university administration’s actions.

Before they spoke, the New School’s former director Wang Hsing-chung had asked current chair Tseng Chien-yuan, “Why don’t we ship it directly to Taiwan?” This was what led to a replica of the pillar being unveiled for the June 4th commemoration of the Tiananmen Square Massacre in Liberty Plaza in Taipei, to mark the 33rd anniversary of the event.

But the project encountered criticisms.

The Pillar of Shame in the University of Hong Kong. Photo credit: Isaac Wong

The Pillar of Shame in the University of Hong Kong. Photo credit: Isaac Wong

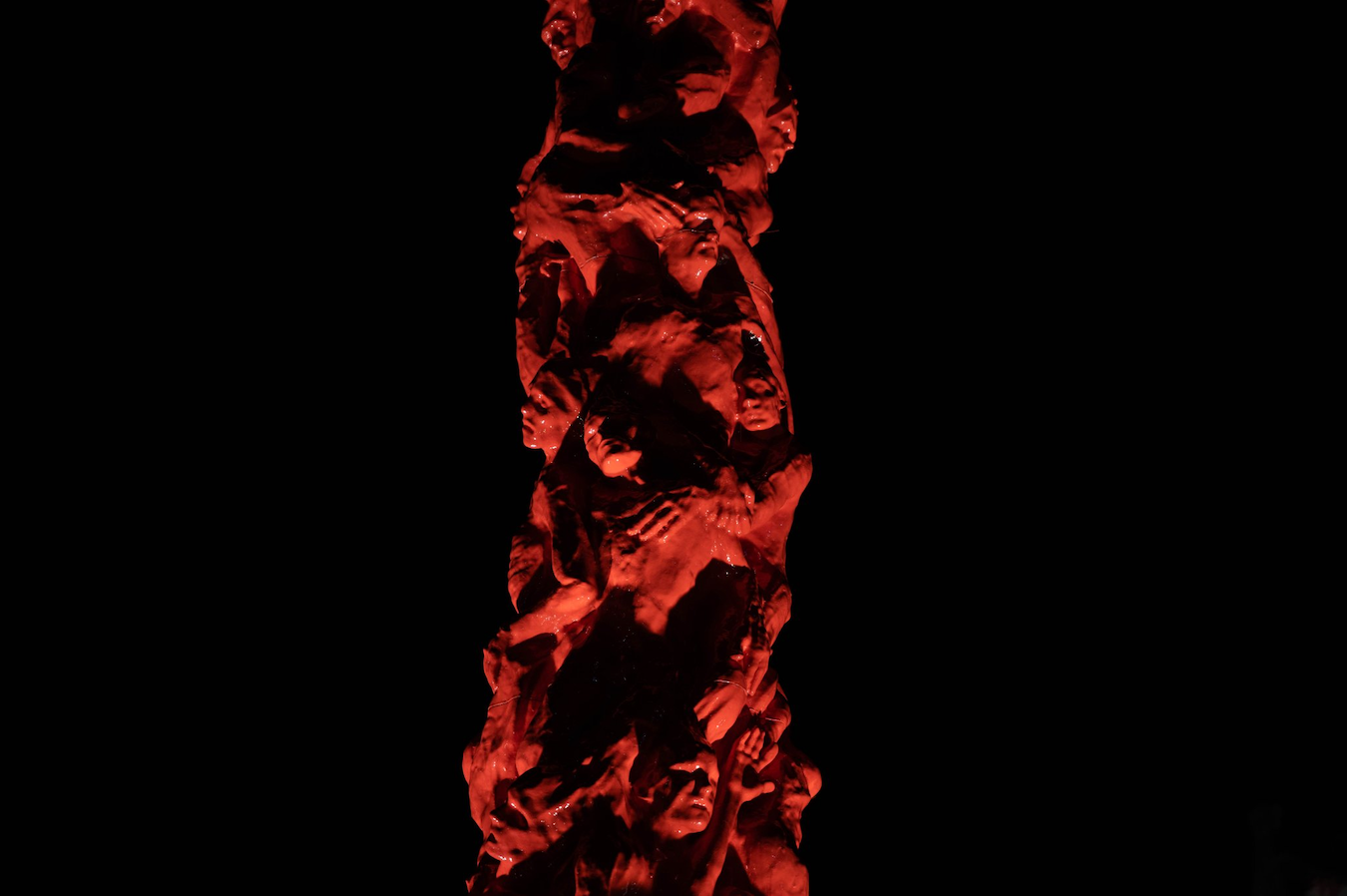

The Pillar of Shame, a sculpture by Jens Galschiøt, was originally displayed in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The pillar served as a form of remembrance for the Tiananmen Square Massacre, which took place on June 4th, 1989. In that sense, the Pillar of Shame Hong Kong represents Hong Kong people’s collective memory of the incident.

The massacre captured the hearts and minds of Hong Kong people, to which they reacted by both watching and protesting. Following demonstrations in 1989, people shouted out the slogan 釋放民運人士、平反八九民運、追究屠城責任、結束一黨專政、建設民主中國 (literally: “release political activists, absolve the 1989 social movement, account the responsibility of the Massacre, end one-party-authoritarianism, and build democratic China”) at the first Victoria Park vigil in 1990.

By 2014, during the Umbrella Movement, the slogan evolved into 平反六四 戰鬥到底 (“absolve the 1989 social movement, fight until the end”); And in 2021, it is 為自由 共命運 同抗爭 (“for freedom, common fate, fight together”). Hong Kong people have been pursuing democracy together with calling for a vindication of the incident.

Former site of the pillar at the University of Hong Kong. Photo credit: Undergrad, HKUSU

Former site of the pillar at the University of Hong Kong. Photo credit: Undergrad, HKUSU

The pillar was originally unveiled in June 1997 and displayed at Victoria Park, during the annual commemoration of the Tiananmen Square Massacre that takes place there. After being displayed at a number of universities in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong University Students’ Union (HKUSU) voted to be the permanent host of the sculpture.

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support for the Patriotic Democratic Movement in China has cleaned the pillar annually since 2002. Even as many activists started being skeptical of the Alliance’s aspirations to “build a democratic China” distanced themselves from the Alliance with the rise of localism in past years, HKUSU still regularly cleaned the sculpture and organized a June 4th commemoration beside it.

The removal of the pillar from the University of Hong Kong occurred at a time of deteriorating political freedoms in Hong Kong, in which acts of censorship and self-censorship are increasingly mundane. Although the university allowed Galschiøt to retrieve the artwork, which had been reportedly sawed into halves, no shipping companies dared to transport the sculpture. As the pillar’s destiny remained uncertain, its former site became a seating area.

Having seen the university’s actions, Tseng wanted to do something to preserve the traces of the incident.

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Thanks to the rise of 3D printing, the New School could replicate the Pillar of Shame at lower costs. It started a crowdfunding campaign on FlyingV, with a 640,000 NT goal for 3-meter-tall replication, and 1,500,000 NT for a 7.5-meter-tall version. 3D printing allowed for cost reduction, as the recreation of the pillar by hand was estimated to be at a cost of 10,000,000 NT.

Unfortunately, the crowdfunding project provoked Taiwan netizens. The controversy was due to the Pillar of Shame’s widely-known Chinese translation 國殤之柱 (literally “Pillar of National Shame”).

Although the New School adopted 恥辱柱 (literally “Shame Pillar”) as its new name, and removed the 國/national part of the phrase, its former translation was been widely used by media and in discussions. In RFA’s and Chaser News’ recent features, featuring interviews with Tseng, the pillar was still referred to as “國殤之柱”.

Among the questions netizens asked were: “Which nation’s shame is this?”, “Why should we commemorate other nation’s suffering?”, and “This business should be left to the Chinese and Hong Kong people, not us Taiwanese.”

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

The artist‘s original intention to create the pillars was not limited to reminding people of the incident.

Galschiøt stated on his website that the sculpture was to remind us of “a shameful event which must never reoccur”, and “[e]ach sculpture will be provided with a base to place it in the concrete local context.” It had not been a “Tiananmen Square Pillar”, as the Pillar of Shame in Hong Kong was among a series of sculptures marking historical tragedies around the world–not just in Hong Kong.

In particular, the artwork’s appearance reflects this demarcation. He sculpted the faces on the pillar to be deliberately ambiguous, so as to present diverse races as universal.

Yet after the HKU’s administration’s actions, Galschiøt now hopes to raise awareness of Hong Kong’s fight for (China’s) justice and democracy through the pillar.

Supporting the campaign, well-known academic Wu Rwei-ren clarified that the project does not limit itself to the Tiananmen Square Massacre but any tragic humanitarian crimes. He argued that Taiwan, as a democratic country, should contribute its part to ending human suffering.

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Another supporter of the plan, DPP legislator Fan Yun, argued the real problem had at its roots the unjustified removal of the Pillar and the acts of mass killing that took place in 1989. Chiang Min-yen of the Economy Democracy Union also stated publicly that he hoped people would stop focusing on the nominal issue but prioritize humankind’s suffering writ large.

While it is hard to measure how persuasive these supporters’ clarifications are, the crowdfunding raised enough money for a 3-meter-tall replica only 2 months after its launch; only 55 people backed the project. The crowdfunding campaign did not meet the threshold for making a 1:1, 7-meter-tall replica. News reported that the campaign had “successfully” met its goal, but in reality it met merely half of it.

Tseng told me further that a large amount was from a single source. “It’s a pity that only 50 people joined our project, though some funded generously to prevent embarrassing results. The outcome is not impressive, the numbers are pale.”

He sighed. The New School’s members had doubts as to whether they could really crowdfund enough money since day 1 of the campaign. Yet they chose to bet on the outcome, to treat it as a test of Taiwan people’s commitment to the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

The results of the FlyingV crowdfunding campaign

The results of the FlyingV crowdfunding campaign

“Taiwanese people crowdfunded fewer than half of the target amount. So let it be, admit that people here are ‘less than half’ concerned with June 4th.”

The novel re-translation of the pillar’s name did not save the New School from controversy. From what the supporters said, their primary intention to replicate the pillar in Taiwan is to fill spaces for commemorating the Tiananmen Square Massacre that Hong Kong has just lost; the commemoration of other tragedies are at best its contingent purpose.

At an Amnesty International webinar on May 14th, Galschiøt responded to my question about the meaning of the pillars. He reiterated that the pillars are still about worldwide human rights tragedies. “There’s a lot of humans in this pillar,” he said. As he set up pillars in Italy for worldwide famine, in Mexico for the Acteal Massacre, and in Brazil for the El Dorado do Carajás Massacre, he thinks the pillars “continue happening” around the world, and the project “has to do with it all.” Nonetheless, he emphasized, “At the moment, nearly everybody believes, if there is one, it is China’s one.”

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Tseng himself acknowledges emotional linkage to the Tiananmen Square Massacre as the root motivation of the New School’s project. “If it was the Brazil’s pillar’s removal, it may not shock us, maybe we would not initiate a similar project; it is because of June 4th, it is because of Hong Kong, that we kickstarted this campaign.”

On its crowdfunding website, the New School explained it “wishes to tell the world that Taiwan cares about freedom of creation and human rights with this opportunity.” Although the descriptor does mention “its meaning does not limit to June 4th Incident,” to them, the pillar is still “filled with the blood and tears of Hong Kong people’s political struggles since 2019.”

The New School held an opening ceremony for its pillar replica at the annual vigil for the Tiananmen Square Massacre in Liberty Plaza, to “stand in silent tribute for victims of June 4th Incident” and “give voices to suppressed victims of CCP.”

Contrary to the New School’s and the artist’s expectation, many Taiwanese people do not see the Tiananmen Square Massacre or its commemoration in Hong Kong as part of their history and as something they should be concerned with. The real issue, then, is the sense of ownership.

Facebook post by Lin Ching-yi of the DPP on the pillar

Legislator Lin Ching-yi of the DPP challenged the project as “one that must be clear which nation’s shame it is before discussing the Pillar of National Shame.” She said, “Taiwan has many times been categorized as a different country, as China. To commemorate a country whose state does not accept this shameful history, would it not be interpreted as commemorating ‘our country’s’ shameful history?”

Lin continues, “Yes, human rights are universal values. Taiwanese concern with Ukraine, China, Hong Kong and Syria and other places are international human rights issues. Yet, at the end of the day, each country needs to first fight for its own survival, before others come to help you.” Her Facebook post received more than 6,600 likes.

Another critic, Taiwan Statebuilding Party Secretary General Wang Sing-huan, said “If the pillar is to remind Taiwan of ‘the danger of being incorporated by China’,” then he supports its establishment.” Yet, “If it is to stress ‘China’s human rights issue is of special concern’,” then he called for dropping the project.

In my interview with Wang, he pointed out that this pillar is not like the others. “Do other Pillars of Shame have ‘Tiananmen Square Massacre’ and slogans sculpted at their base?”

To him, the only acceptable meaning of the New School’s replicated pillar is to make people aware of the danger of China’s annexation. To some of his colleagues, even this is not acceptable. “They will ask, ‘why must we be reminded of it by this sculpture?’”

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

The New School was founded in Hong Kong and Taiwan in 2011. 15 years younger than the original in Hong Kong, it aims to promote democracy of Chinese societies, and to exchange ideas across Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Tseng thinks it is understandable that younger localists feel remote to China. Contrasting older localists, who utilized identity politics to counter Taiwan’s previous authoritarian regime, and were educated under a system that taught a pan-Chinese mindset. To younger localists, they have no common experience with struggles and calamities in China, so they can hardly feel the history.

With regards to localist discourse, Tseng said, “When ‘Taiwan is Taiwan, and China is China’ is highlighted in debates surrounding this campaign, one needs to emphasize Taiwanese agency and consciousness, and to rule out all that relates to China. The whole discussion is an ‘all or nothing’, an absolute debate.”

According to National Cheng Chi University’s Election Study Center, Taiwan’s population increasingly identifies themselves as “Taiwanese;” this rose from 17.6% in 1992 to 62.3% in 2021. In contrast, identification as “Chinese” and “Both Chinese and Taiwanese” dropped from 25.5% to 3.2% and 46.4% to 31.7% respectively. Moreover, only several hundred participated in annual Tiananmen Square Massacre vigils.

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Tseng deems the so-called “natural independence generation (天然獨)” as itself being a natural phenomenon. Taiwan and China people differ across not only with regards politics, but also with regards culture, public life, and other aspects. “Even though there were frequent exchanges between two sides during Ma Ying-jeou’s presidency, the Sunflower Movement eventually took place. “Just like the saying goes, ‘We get acquainted by misunderstanding, and get separated by understanding’,” he commented.

In his book, In Praise of Forgetting, David Rieff argues that “the essence of historical remembrance consists of identification and psychological proximity.” Indeed, Taiwanese localism or nationalism may perceive itself as threatened by commemoration of events in China.

Facing this hurdle, Tseng said, the New School has sought to shift its discourse from one founded ethnic/cultural Chinese identity to universal human right values. “Even if we have different starting points, we can still agree on the fact that democracy of China is not a foreign problem. When China does not treasure democracy and universal values, it will be hostile to Taiwan, which is disadvantageous to us.” Tseng thinks Taiwan interests are best served when it seeks connections with other oppressed peoples of CCP.

At Taiwan’s annual commemoration of the Tiananmen Square Massacre this year, Tseng estimated more than one thousand people participated. He told participants in his speech that “Taiwan needs to show its determination to protect its democracy.”

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Tseng argued that treating June 4th as Taiwan’s own business is not just because of emotional linkage to China, but also for pragmatic reasons. “If China does not democratize, how could Taiwan be substantially independent?”

But a Chinese student at the rally, D., told me that he “can clearly feel how marginalized June 4th is in Taiwan. Most Taiwan people deem it as another country’s affairs, not their business.”

“I’m not in the position to comment on their point of view. Still, there’s one thing that I’m grateful to Taiwan. That is at least memorials that are allowed. I can commemorate the incident here.”

The fact that many of this year participants were from Hong Kong, shows that June 4th sparked solidarity within the migrant Hong Kong community. Yet this is also where the problem lies: it seems barely able to reach out to locals.

Zoe Chiang, a Taiwanese graduate student, told me that, “I’m not sure if Taiwan should be an anti-CCP base.” She thinks Taiwan has its own problems and is lacking consensus. “I do support opposing the CCP, but do Taiwan, China and Hong Kong share the same priority, goals and agenda? I don’t think so.”

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

Photo credit: Chan Sai Ho

This replica gave her an ambivalent feeling, “It doesn’t seem fit to this place, a venue in front of the KMT authoritarian regime landmark, whose transitional justice we’re still dealing with.”

For Ma Yang-yi, a final year undergraduate, it would be great if the pillar could inspire participants to deliberate about June 4th, instead of merely mourning the tragedy. “But so far I don’t see how this can be accomplished in Taiwan. The pillar is more placed under the Hong Kong context, and it doesn’t have a proximate meaning to Taiwan people.”

Huang Shu-mei, Associate Professor at the Graduate Institute of Building and Planning at National Taiwan University, thinks it is hard to transplant memory overseas. “The Tiananmen Square Massacre has been fading away from public memory. If the replica cannot connect with enough locals, the memory of June 4th can hardly be passed on to Taiwan society.”

The New School has replicated the Pillar to continue commemorating the Tiananmen Square Massacre. The challenge for the organization now is to connect the Pillar with its new recipient, the Taiwan society. But with the uninspiring crowdfunding outcome, weak local participation of memorial events, and Taiwanese’s pessimistic reactions, it may be that the New School and the replica still have a long way to go.