by Wendy Cheng

語言:

English

Photo Credit: AP/Keith Srakocic

IT WAS THE summer of 1975. The two young Taiwanese men, Rocky Tsao (曹永愷) and Chen Wen-chen (陳文成), met again in Ann Arbor, Michigan at a Taiwanese Association social gathering. Like most Taiwanese in the U.S. at the time, they were graduate students—Chen in statistics and Tsao in biochemistry.

Tsao remembered first meeting the energetic and stockily-built Chen two years earlier in Taiwan when both had been serving their mandatory military service as part of the chemical corps, Chen serving as an instructor. Now, nearly five decades later, speaking to me on the phone from Boston, Tsao still recalls how Chen wore his military issue-hat rakishly tilted, “intentionally very sloppy.” “The image of him with a tilted cap, an attitude like, ‘I was forced to be here,’ confident in spirit, is deeply etched in my mind.” [1] Further, Tsao remembers, Chen refused to live in a dorm and spent money to live separately, on his own. “Can you believe it?” Even in his early twenties, then, under direct KMT military supervision, Chen had a rebellious spirit and refused to be controlled.

Chen Wen-chen. Photo credit: Historical Photo

Chen Wen-chen. Photo credit: Historical Photo

Six years after that youthful and joyous summer in Michigan, on July 3, 1981, Chen’s body was found on the campus of National Taiwan University in Taipei, his undergraduate alma mater, at the foot of a five-story building. At the time, he was 31 years old and an assistant professor of statistics at Carnegie Mellon University. The basic outlines of the story are well-known: The morning of the day before, Chen had gone in for questioning by the Taiwan Garrison Command regarding his political beliefs and activities in the United States. After that, his family—which included his wife, Su-jen (陳素貞) his one-year-old son, Eric, his parents, and seven siblings—never saw him alive again.

Chen’s case became known internationally and, in the US, was the subject of two congressional hearings. It made the question of KMT spying on US campuses—broadly acknowledged to have been a factor leading to Chen’s interrogation by the Garrison Command—a matter of national concern. And it galvanized Taiwanese in Taiwan and in the diaspora to continue their struggle for democracy and the end of martial law in Taiwan.

In the forty years since Chen’s death, within Taiwan and in its diaspora, Chen has been remembered as a kind and courageous person, a brilliant scholar, a loving husband and father, and a martyr for Taiwan independence. As former Associated Press reporter Tina Chang (周清月, who herself had been embroiled in the KMT’s attempts to control the coverage of Chen Wen-chen’s death in 1981) summarized it in 2003:

“Chen Wen-chen was a political unknown when he was murdered at age 31. In life he was one of many discontented, outspoken overseas Taiwanese academics with a passionate longing for a better homeland. In death, he became a hero, eulogized along those martyrs who gave their lives to the cause.” [2]

English-language newspaper reports immediately following Chen’s death generally characterized Chen as a political moderate, while narratives from the Taiwanese community foregrounded his anti-KMT, Taiwanese independence politics. In 1991, the US-based Chen Wen-chen Memorial Foundation wrote:

“His beliefs were straightforward. He believed that since the native Taiwanese make up 85% of the 17-18 million people on Taiwan, that they should be able to share some of the legislative responsibilities and powers of that country with the Chinese Nationalist officials.” [3]

And yet, percolating around the edges, were hints of more complicated narratives.

At a memorial in Ann Arbor, Michigan, less than three weeks after Chen’s death, a Hong Konger friend of Chen’s complained to a reporter that because the “right– wing” Taiwanese independence activists had been in charge of the service, “they made it sound as if Chen was on the right, when in fact he was on the left wing of the Taiwanese independence movement.” [4] Similarly, less than a week after Chen’s death, a student official of University of Michigan’s Free China Student Association commented that he had met Chen three years earlier and thought he was “very interested in socialism”—an ominous comment from a representative of an organization that was widely believed to have Kuomintang informers in its ranks. [5]

In fact, Chen’s politics—and the 1970s-1980s politics of Taiwanese independence activism more broadly—were more complex than is often understood today, particularly in Taiwanese American communities and more broadly in the US.

REUNITED THAT summer evening in Ann Arbor in 1975, Chen and Tsao hit it off right away, walking home together and chatting late into the night. Over the next three years, the two men became so close they addressed each other as “brother”; both became immersed not only in their intellectual life and work, but in the social and political life of Taiwanese and Chinese-identified students.

Like many other Midwestern university regions at which large numbers of students from Taiwan landed during the 1970s-1980s, Michigan, where Chen and Tsao lived from 1975-1978 while studying for their Ph. Ds, was a hotbed of diasporic political contestation. As in numerous other US college towns, they sorted themselves into roughly three groups: Chinese-identified, pro-KMT students from Taiwan; Chinese-identified, pro-China and anti-KMT students from Hong Kong; and Taiwanese-identified, anti-KMT students from Taiwan. Among the third group, there was also a subset of students who identified as Taiwanese but were interested in China and friendly with the students from Hong Kong. For most, if not all, of his time living in Ann Arbor, Chen Wen-chen fell into the last category.

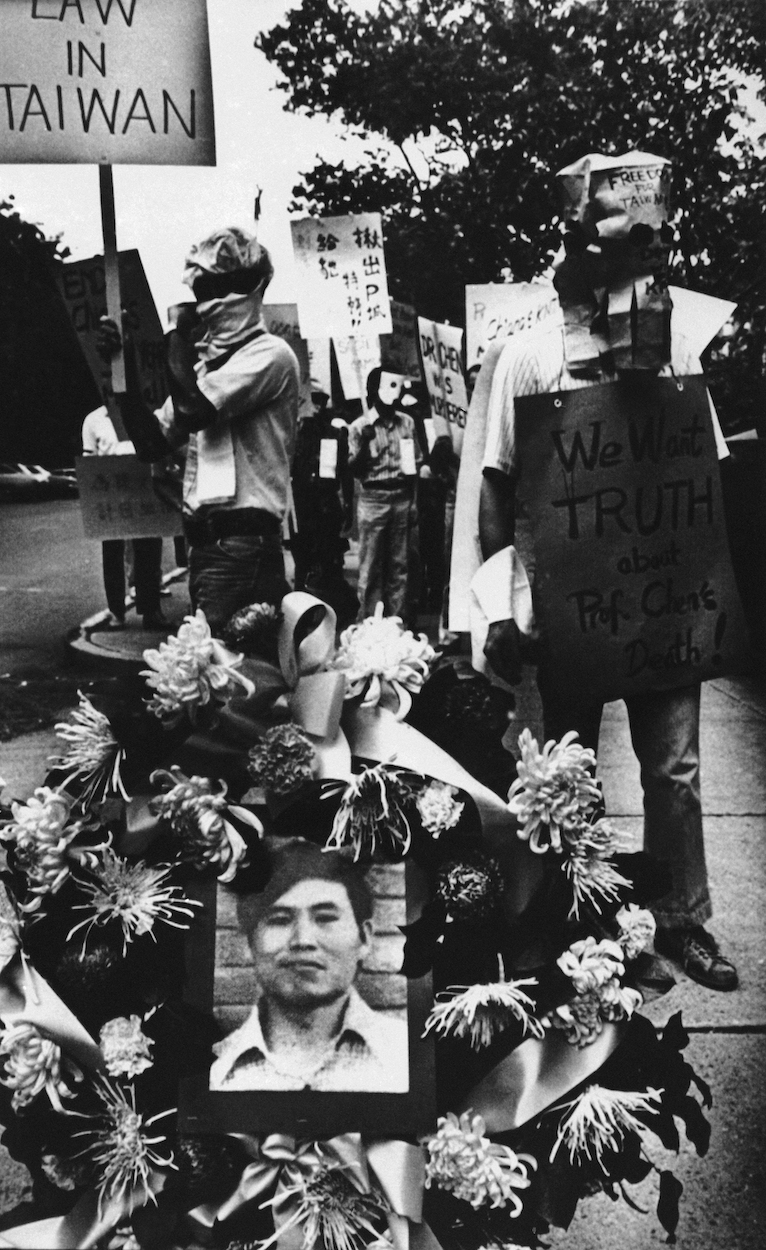

Taiwanese students and friends of Chen Wen-chen gather on the campus of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh on July 18, 1981, after a memorial service for Chen. Photo credit: AP/Keith Srakocic

Taiwanese students and friends of Chen Wen-chen gather on the campus of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh on July 18, 1981, after a memorial service for Chen. Photo credit: AP/Keith Srakocic

In other words, Chen, like other students from Taiwan and Hong Kong in the diaspora, was part of a Sinophone sphere of political discourse in which idealism and vigorous dissent were the norm.

Born in 1950, Chen had grown up in the countryside of what was then Taipei County, and often recalled to friends how difficult it had been for his parents, planting tea leaves and raising eight children. [6] In the 1970s, reflecting on his childhood as a young man in his twenties, Chen was inspired and moved by the Taiwan “native-soil” writers. According to his friend “N,” Chen enjoyed reading the writings of Huang Chunming (黃春明), Chen Yingzhen (陳映真), Wang Tuo (王拓), and Yang Qingchu (楊青矗); he especially “related deeply” with the characters in Chen Yingzhen and Huang Chunming’s short stories. “He loved talking about this literature because these stories not only brought up memories of his childhood, they also empathized with the poor working class community in the same way Chen Wen-chen did,” Rocky Tsao wrote in 1982. [7] As editor of the Ann Arbor Taiwanese Association’s newsletter, Chen started a regular column on Taiwan literature, and was enraged when the KMT banned native-soil literature in 1977.

In everyday life as well—on the athletic fields and courts he loved, and among his friends—Chen was known to be a highly empathetic person with a “passion for fairness.” “A person with such a strong view of equality and rich compassion naturally leaned a bit towards socialism,” Tsao wrote in 1982, and confirmed again over the phone this summer. [8] Along with leftist activists, intellectuals, and working-class people around the world, Chen was deeply inspired by the socialist revolution in the PRC.

In Ann Arbor, he was friendly with both pro-independence and pro-unification factions among Taiwanese and Hong Konger students, observing, however, that “most overseas Taiwanese are scared of communism. If you talk about communism, most people will think you are pro-unification.” This, he felt, was “not very healthy.” [9] From 1975 to well into 1978, “Chen was very impressed by China’s ability to turn upside down from a man-against-man society to a bountiful society.” [10] Chen’s friend “N” concurred, recalling that Chen praised “Chinese people” for having “relied on their own strength to go from a poor and weak country to one that is admirable to others. Now the people are living well and have a fair socialist system…. This is what the Taiwanese people can learn from them.” [11] Chen even dedicated his Ph. D thesis to China and his “fellow citizens who work diligently in the country fields and urban factories for the greater advancement of society”—a bold move for the time, considering that such a dedication would certainly have been seen as a crime under Taiwan’s martial law.

However, by late 1978, Chen, like many others, became disillusioned by the PRC, feeling that the CCP’s authoritarian rule had compromised its avowed politics. From that point on, he distanced himself from friends who remained pro-unification, while turning his political energies to fundraising to support Formosa Magazine (美麗島) and the democracy movement within Taiwan. After the Kaohsiung Incident in December 1979, in which democratic movement leaders were rounded up and arrested, Chen was “heartbroken,” feeling that “ethnic oppression [of Taiwanese people] is the root cause of all injustices and inequalities in Taiwanese society—including politics that are against democracy—and he became one of the strongest advocates of Taiwanese nationalism.” [12]

Specifically, Chen “strongly supported the term 台灣民族 (Taiwan minzu)”—a term denoting a distinctive Taiwanese nation or people (not ethnically exclusive). While not readily translatable to English, considering this term’s historical and contemporary usage in China (“中華民族” Zhonghua minzu) to unite—or claim (depending on one’s feelings about it)—disparate ethnic groups in China and the diaspora under one Chinese identity, the term Taiwan minzu in historical and political context can be understood as an anti-colonial move of self-determination, as well as a rejection of Han chauvinism.

What never changed, however, was Chen’s unwavering commitment to working-class people and his steadfast love of Taiwan. He believed that the “political action of Taiwanese people should never leave the platform of hardworking Taiwanese laborers. When I participate in any political movement, I must think through what my position is and make sure that everything I write about is focused on the native Taiwanese. If it departs from focusing on native Taiwanese, it is not truthful.” [13]

After moving to Pittsburgh in 1978 to begin his career as a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, Chen continued to be ardently involved in political discussions and dialogue. A Pittsburgh friend recalled, for example, that Chen volunteered his house in Squirrel Hill as a meeting space for Taiwanese Association biweekly “open house” discussions that often became so heated that people “would be hitting tables, throwing chairs, etc. while discussing politics.” [14]

While in Pittsburgh, Chen became particularly interested in the ideas of the leftist, pro-independence group, Taiwan Era (台灣時代), one of whose leaders, Zheng Jie (鄭節; a pseudonym) was also a professor living in Pittsburgh. Taiwan Era took a Marxist-Leninist line and elaborated more deeply and in a more explicitly internationalist fashion the general ideas espoused by an earlier diasporic leftist publication headquartered in Toronto, Taiwan Revolution (台湾革命). In addition to including articles on anti-imperial struggles around the world, Taiwan Era also sought to highlight past anti-colonial struggles and leftist organizations within Taiwan as part of “400 years of Taiwan revolution,” adopting Su Beng’s (史明) historical framing in Taiwan’s 400-Year History. Taiwan Era criticized the dominant independence activist group, World United Formosans for Independence, for playing on ethnic divisions and lacking a progressive class analysis. They believed that organizing workers and class struggle were necessary to achieve a truly liberated future for Taiwan.

Rocky Tsao recalled that once, after reading an article from Taiwan Era, Chen was so inspired that “he excitedly copied it and shared it with everyone.” [15] In aligning himself with Taiwan Era during his Pittsburgh days, Chen continued to be part of a leftist strand in the Taiwanese pro-independence movement, one that did not see socialist values and Taiwanese self-determination as contradictory goals. This false binary, an ideological inheritance of the Cold War, extends from a conflation of democracy with capitalism and the virulent anti-communism of both the US and—ironically—the KMT. It persists in much of the Taiwanese American community today.

WHAT, THEN, SHOULD we—especially as Taiwanese and Taiwanese Americans—make of Chen’s political legacy today?

For independence-minded Taiwanese, Chen was and remains a martyr and a hero. In the months after Chen’s death, it was common for his supporters to express, as Carnegie Mellon University President Richard Cyert did at Chen’s September 11, 1981 memorial service in Pittsburgh, that:

“…we must pledge ourselves to fight for the elimination of the police state that now exists in Taiwan. We must become part of this fight for independence that a small number of Taiwanese are now making as a part of the tribute to a colleague who was murdered for believing in democracy.” [16]

Another supporter, described only as an “anti-government activist,” stated simply: “Chen died for our sins… He is clearly a political martyr. His murder was meant to intimidate us.” In the same article, Los Angeles Times reporter Michael Park summarized it: Chen was “haunting Taiwanese politics, and his friends and family say that his spirit will not rest until justice is done.” [17] A year after Chen’s death, in 1982, friends and acquaintances published a memorial collection that was widely circulated in the U.S. as well as in Taiwan (although predictably, the KMT tried to suppress the book wherever it appeared). The inside title of the page, in English, read: “A Memorial for Professor Chen Wen-Chen—A Taiwanese.” The preface stated, in part: “The death of Wen-chen is the tragedy of Taiwanese people…His spirit must become the strength of Taiwanese people—for us to finish what he started, so that his soul may be at peace.” [18]

This past February, a memorial to Chen at National Taiwan University was finally dedicated after ten years of struggles, “rejection and stalemates with conservative school administrations.” NTU president Kuan Chung-ming (管中閔)—who himself had created a major obstacle to its construction by rescinding the university’s promised half of the funding in 2019—stated that Chen’s death “shocked people to their core, awakening Taiwanese to the pursuit of human rights, democracy and freedom.” The memorial “also serves as a reminder of the other heroes who fought for Taiwan’s future, [Kuan] said, calling for timely clarification of the truth so that the departed could be afforded peace.” According to NTU Students’ Association president Yang Tzu-ang (楊子昂), the memorial—which resembles a large, opaque black box slightly tilted and with an opening in the middle—“was designed around the concept of ‘emptiness’ to represent the opacity of historical truth, and the blank terror of prison cells and interrogation rooms.”

Chen Wen-chen Memorial on the National Taiwan University campus. Photo credit: Presidential Office/Flickr/CC

Chen Wen-chen Memorial on the National Taiwan University campus. Photo credit: Presidential Office/Flickr/CC

In Taiwan, then, the legacy of Chen’s death is still an unfinished one, symbolizing the lack of full answers, closure, and perhaps most important of all, accountability.

What, however, is the political legacy of Chen’s life? As a scholar who has been studying Taiwanese American migration and political activism for the past ten years, I offer the following reflections: First, let us remember that Chen was a dedicated leftist, committed to the struggles of working-class people and to a project of global liberation that was bigger than Taiwan. Chen’s specific political commitments must be included as part of his legacy, as well as part of the broader legacy of Taiwanese activism for democracy and independence. Second, we should commemorate Chen as part of a vigorous Sinophone sphere of political discourse. By “Sinophone,” I mean not only in a linguistic sense but sociopolitically, encompassing anti-nationalist, anticolonial, and decolonial possibilities (as initially posited by Shu-mei Shih and since elaborated by an entire field of study). Such orientations anchor us in an ideologically heterogeneous past in order to envision and act upon political futures for Taiwan that are not limited by ethnic nationalist claims on both sides of the strait.

Relatedly, we should embrace the unruliness of Chen’s political commitments and reflect on how and why they do not fit neatly into the identitarian and political frameworks that have hardened since Chen’s time. As Rocky Tsao put it in 1991, ten years after his friend’s death:

“Wen-chen had a bold personality and was not suited to strict organization of life. He did not join any political group throughout his life. However, he was a person with an extremely strong sense of equality and justice. He sympathized with the poor in Taiwan and hated the trauma caused by the Kuomintang’s ‘provincial’ discriminatory policy and dictatorship and repressive rule. Naturally, after he went abroad, he became interested in socialist ideas on the one hand, and on the other hand, he actively participated in the activities of the Taiwanese Association and other Taiwanese associations.” [19]

Chen was someone who was both deeply idealistic and deeply intellectual—willing to cross commonly accepted boundaries, explore every possibility, and dialogue with anyone. (For example, Tsao recounts a story of how Chen openly challenged a KMT member who was the son of a general. Another time, as vice president of the Ann Arbor Taiwanese Association, Chen went alone to a Chinese Association orientation to promote the Taiwanese Association to new students: “Seeing Wen-chen alone, swaggering over to participate in their activities, [that] KMT member was speechless for awhile.”) [20]

During and since the martial law period, it is likely that the “chilling effect” of nearly four decades of political indoctrination, persecution, intra-community surveillance, and outright terror (including the murder of Chen)—never fully addressed or reconciled—persist as calcified psychological fractures on the political imaginations of many Taiwanese who endured those times as well as their descendants. Can we —Taiwanese in Taiwan as well as in the diaspora—now break free of those fractures in order to recover the youthful and full possibilities of Chen’s bold political ideals and imagination?

In 1981, not long before his fateful trip to Taiwan, in an unfinished letter to Tsao (included in the 1982 memorial collection), Chen was still strategizing—how best to keep organizing in support of the democratic movement in Taiwan at an upcoming regional softball tournament in Columbus? The letter was thoughtful and exuberant, peppered with exclamation marks. He ended the unfinished letter with the following paragraph:

“I’ve been listening to some Taiwanese pop songs recently! I used to hum them when I was a child! After all, feelings/emotions are still one of the cores of human life! The KMT’s ruthless tactics in Taiwan cannot eliminate the spirit-filled lives of the Taiwanese! This is one of our most advantageous qualities!” [21]

Today, forty years after Chen’s tragic death, let us not only mourn his unjust killing, but fully commemorate his “spirit-filled life”: his active engagement in a politics that was centered on a vision of Taiwan as part of a more just and liberated world; his bold and unruly legacy.

[1] 葉常青 (Ye Chang Qing, a pseudonym), “懷念一位殉鄉的好友 (Remembering a Friend Who Died for His Homeland)”; A Memorial for Professor Chen Wen-Chen – A Taiwanese (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Professor Chen Wen-chen’s Memorial Foundation, 1982), pp. 143-49. Special thanks to Daphne Liu and Shu-ching Cheng (賴淑卿) for their translation assistance.

[2] Tina Chang, “A Political Death and Media Casualty,” Taiwan News, December 10, 2003.

[3] “Professor Chen Wen-chen Memorial Foundation,” 麥子落地 (Sowing the Seeds) (Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Chen Wen-chen Memorial Foundation, 1991), p. 176.

[4] John Adam, “Official Concurs: Spies on Campus,” Michigan Daily, July 21, 2981.

[5] John Adam, “Taiwanese Here Fear Murder,” Michigan Daily, July 9, 1981.

[6] “N” (a pseudonym), “憶好友陳文成 (Remembering a Good Friend, Chen Wen-chen),” A Memorial for Professor Chen Wen-Chen – A Taiwanese (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Professor Chen Wen-chen’s Memorial Foundation, 1982), pp. 178-85.

[7] 葉常青 (Ye Chang Qing, a pseudonym), “懷念一位殉鄉的好友 (Remembering a Friend Who Died for His Homeland).”

[8] 葉常青 (Ye Chang Qing, a pseudonym), “懷念一位殉鄉的好友 (Remembering a Friend Who Died for His Homeland).”

[9] “N” (a pseudonym), “憶好友陳文成 (Remembering a Good Friend, Chen Wen-chen).”

[10] 葉常青 (Ye Chang Qing, a pseudonym), “懷念一位殉鄉的好友 (Remembering a Friend Who Died for His Homeland).”

[11] “N” (a pseudonym), “憶好友陳文成 (Remembering a Good Friend, Chen Wen-chen).”

[12] 葉常青 (Ye Chang Qing, a pseudonym), “懷念一位殉鄉的好友 (Remembering a Friend Who Died for His Homeland).”

[13] “N” (a pseudonym), “憶好友陳文成 (Remembering a Good Friend, Chen Wen-chen).”

[14] 金永和 (Jin Yong He, a pseudonym), “陳文成在匹茲堡 (Chen Wen-chen in Pittsburgh),” A Memorial for Professor Chen Wen-Chen – A Taiwanese (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Professor Chen Wen-chen’s Memorial Foundation, 1982), pp. 152-54.

[15] 葉常青 (Ye Chang Qing, a pseudonym), “懷念一位殉鄉的好友 (Remembering a Friend Who Died for His Homeland).”

[16] Statement by Richard Cyert, Wen-chen Chen Memorial Service (Dr. Chen Wen-Chen Memorial Foundation Archives; Taipei, Taiwan).

[17] Michael Park, “Taiwan Haunted by Ghost of Educator,” Los Angeles Times, October 7, 1981.

[18] A Memorial for Professor Chen Wen-Chen – A Taiwanese (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Professor Chen Wen-chen’s Memorial Foundation, 1982).

[19] 李直 (Li Zhi, a pseudonym), “台灣人還有救嗎? (Can Taiwan Still Be Saved?),” 麥子落地 (Sowing the Seeds) (Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Chen Wen-chen Memorial Foundation, 1991), pp. 66-70.

[20] 李直 (Li Zhi, a pseudonym), “台灣人還有救嗎? (Can Taiwan Still Be Saved?).”

[21] Chen Wen-chen, Unfinished Letter, A Memorial for Professor Chen Wen-Chen – A Taiwanese (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Professor Chen Wen-chen’s Memorial Foundation, 1982), p. 226.