by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Studio Incendo/Flickr/CC

TEN PRO-DEMOCRACY activists were sentenced to jail earlier this week in Hong Kong in the latest action by China as part of a months-long political crackdown. The sentencing takes place on the basis of participating in unauthorized assemblies on August 18th and August 31st in 2018, with the possibility of further charges down the line.

Most English-language coverage has to date focused on the arrest of the most experienced of the pro-democracy activists. This includes 82-year-old Martin Lee, historically viewed as the leader of the pan-Democratic camp and the most senior lawyer in Hong Kong, and the owner of the Apple Daily, 73-year-old Jimmy Lai. Fellow lawyer Margaret Ng, 73, who played a pivotal position in the Civic Party, was also sentenced to jail. Lee and Ng are both former members of the Hong Kong Legislative Council (LegCo).

Martin Lee. Photo credit: Raymond Yam/WikiCommons/CC

Martin Lee. Photo credit: Raymond Yam/WikiCommons/CC

Apart from Lai, all others sentenced are former legislators. This includes leftist activist “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, Lee Cheuk-yan, Cyd Ho, Yeung Sum, Leung Yiu-chung, Albert Ho, and Au Nok-hin. While most of these individuals are in their sixties or older, Au Nok-hin, a former member of Left21 and a convenor of the Hong Kong Civil Human Rights Front, is the youngest at age 33. Leung Yiu-chung has the shortest sentence of eight months, while the longest sentence is faced by Leung Kwok-hung.

Martin Lee, Margaret Ng, Leung Yiu-chung, and Yeung Sum, face suspended sentences, which means that they will not be sent to jail and will instead be on probation—this may be a move to try and present the appearance of leniency. Jimmy Lai, Martin Lee, and Albert Ho intend to appeal their sentences.

Previous waves of arrests have targeted younger politicians, but in targeting veteran politicians, the Hong Kong government may be aiming to show that no one is safe from potential targeting. As many of those sentenced are facing other charges, with the possibility of life imprisonment under the National Security Law passed by the Chinese government, it is probable that the sentences will increase in length. Jimmy Lai was likely included in the wave of arrests in order to send a signal to the media establishment in Hong Kong that free speech could potentially result in a jail sentence.

The pan-Democratic camp no longer has representation in LegCo, with the pan-Democratic camp having resigned en masse in November after last year. This took place because of new powers granted to Hong Kong’s executive branch of government by China’s National People’s Congress (NPC), allowing them to remove legislators at will from LegCo, circumventing the Hong Kong court system. After several legislators were targeted by the new powers, the pan-Democratic camp as a whole resigned in protest, with the recognition that further resistance with LegCo would be futile if legislators could be removed from office at any given time. The pan-Democratic camp had beforehand been using their position in LegCo to block bills proposed by the pro-Beijing camp.

Changes to Hong Kong’s electoral system that were passed in March by the NPC and unveiled in April aimed to prevent the pan-Democratic camp from winning seats in LegCo in the future. Though the total number of LegCo seats was increased from 70 to 90, the number of seats that could be directly elected by members of the public was reduced from 35 to 20—it was already the case that half of the seats in LegCo were not directly elected by the public, but by corporate interests allowed a direct seat in government as a part of the “functional constituency” system. A new body of forty seats in LegCo will not be directly elected by the public or chosen by functional constituencies, but by the election committee that decides Hong Kong’s leader, the Chief Executive.

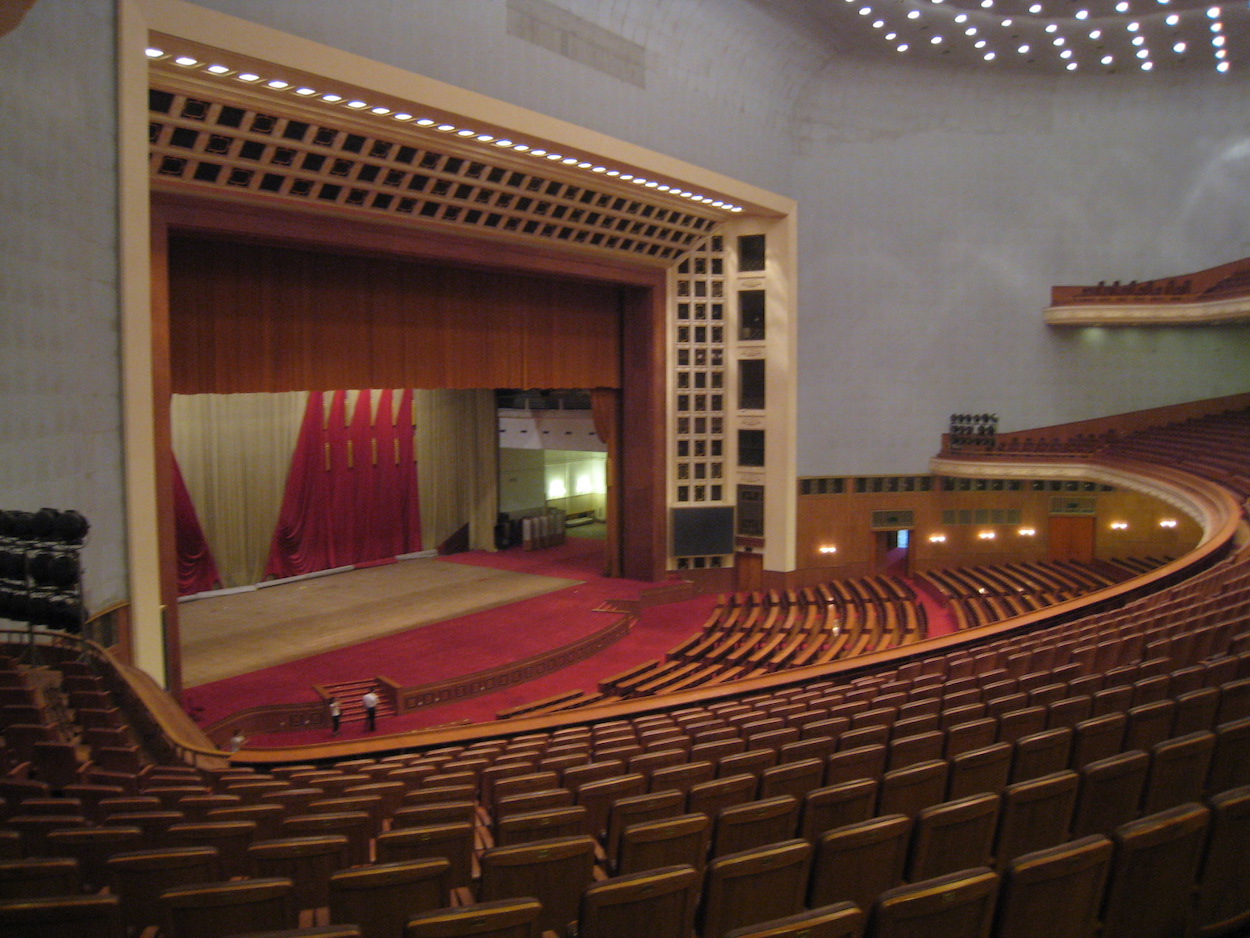

Photo credit: Acidbomber/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Acidbomber/WikiCommons/CC

While this committee also saw its number of seats expanded from 1,200 seats to 1,500 seats, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a political consultative body whose members are chosen by the Chinese government, and other pro-Beijing organizations in Hong Kong. Seats on the Chief Executive selection committee drawn from district councilors, one of the last positions in which pro-democracy politicians could conceivably hold office, were also removed.

The Chinese government clearly has no intention of hedging its bets in Hong Kong, then. Apart from strict legal punishments meted out against pro-democracy politicians, the Chinese government has simultaneously moved to prevent future pro-democracy politicians from being elected through structural reforms—strengthening even the previous tactic of blocking candidates it found unsuitable from running for office or removing them once in office. Journalists are also among those targeted, as with the conviction today of award-winning journalist Bao Choy for searching a publicly accessible database. Newly proposed legislation even suggests granting the Hong Kong government new powers that could prevent people from leaving the city, with no need for the government to go through the court system. One expects this trend to continue.