by Yen-Ting Chen

語言:

English

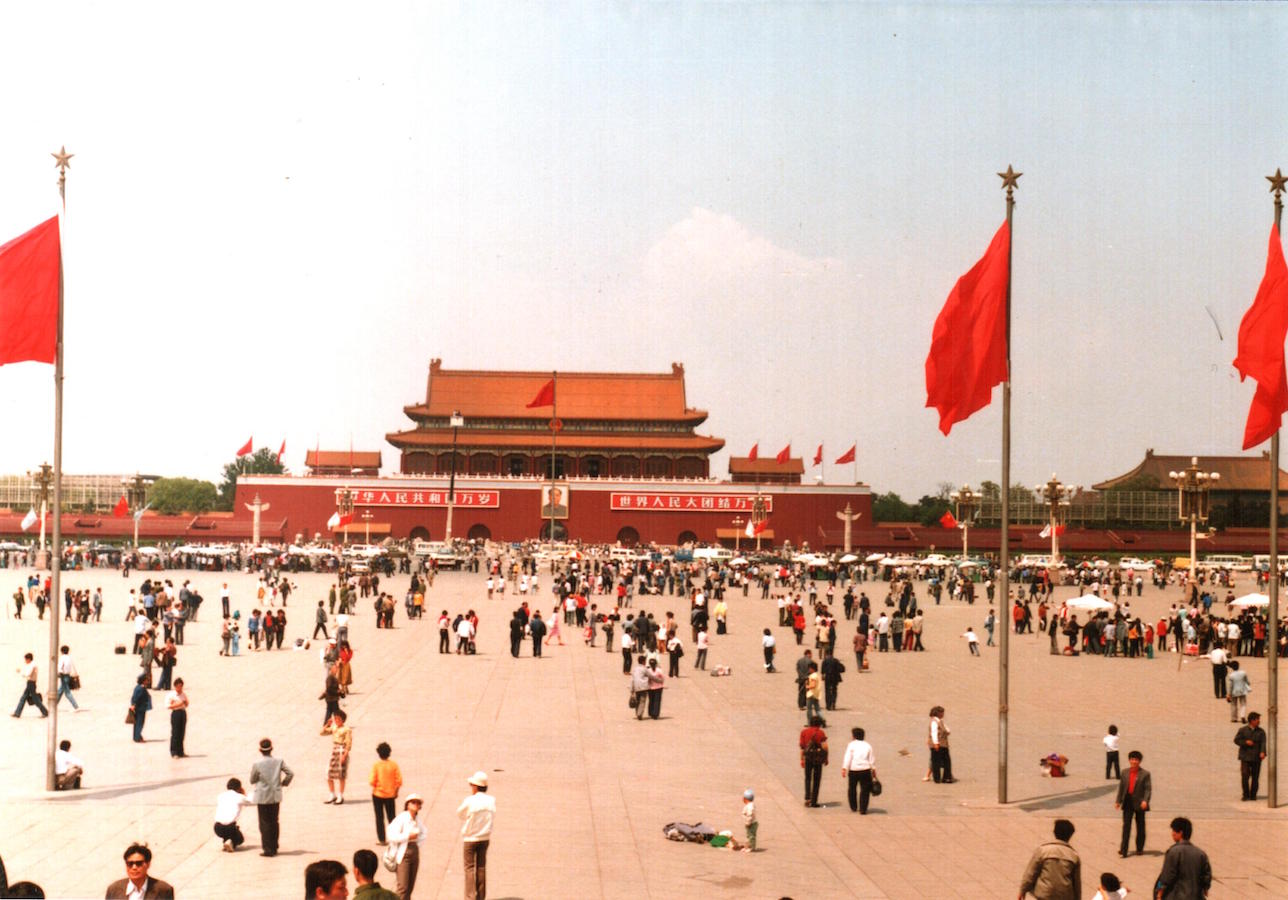

Photo Credit: AlexHe34/WikiCommons/CC

PASSING THROUGH the crowds in Chengdu Shuangliu International Airport, Mou Yanxi felt extremely anxious. She imagined herself being stopped by the customs officer and then taken away by the police, which has happened to many other dissidents.

“Sink or swim, ” the 37-year-old thought. She scanned her passport and fingerprints in front of the ePassport gate. Green-light! Quickening her pace, Mou boarded the plane without looking back. In November 2019, she landed in Britain, having escaped from the Chinese authorities’ control.

Mou Yanxi. Photo courtesy of Mou Yanxi

Mou Yanxi. Photo courtesy of Mou Yanxi

In 2010, just after Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Mou was detained for twenty hours by the Chinese police for supporting Liu on Twitter. Since then, she had been under police watch, which constrained her from traveling during politically sensitive periods such as the days around June 4, the Tiananmen Square Massacre’s anniversary.

Despite the ongoing surveillance, Mou still engaged in human rights activities secretly, at the risk of being arrested. Since February 2015, she has been documenting, tracking, and publishing on human rights violation incidents in China, collecting data from social networks, official documents, mass media and social media. She has covered an average of 150 cases per month for Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch (CRLW), a Chinese news website covering rights issues such as police abuses and government corruption. During this time she witnessed the founder and five members of CRLW’s staff charged and imprisoned, one by one.

“A few NGOs such as Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch gather information and watch the government, which is risky yet essential for rights movement in China,” said Teng Biao, an exiled Chinese human rights lawyer and currently Grove Human Rights Scholar of the City University of New York. “They pass the information out so that international society knows human rights conditions inside China. Besides this, they’ve formed a mutual aid network consisting of activists and victims of state violence.”

However, these NGOs have been almost strangled by the ever more draconian policies imposed by the Xi Jinping regime. “Civil society was growing in China during the former Chinese leader Hu Jintao’s tenure, whereas it is now shrinking under Xi’s stricter control over the press and the internet,” Teng said.

Mou, now living in a city in the north of England, narrated her life story to New Bloom, describing how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has suppressed civil society.

Born in 1982, Mou was raised in a liberal family in Chongqing City. Both of her parents were victims of the CCP regime. Her father, the son of a distinguished academic who fled to Taiwan after the Chinese civil war, spent twenty years in jail after 1957 for criticizing the CCP. Her mother came from a “Black Five Categories” family and was forced to work for the rest of her life in a factory. Being skeptical of the authorities, they encouraged Mou to read and think for herself. “They educated me to be an objective observer so that I have the ability to see the bigger picture,” Mou said.

In her account, Mou has distrusted the Chinese government since she was seven. The 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre shattered her illusions about the CCP-led China. “When a government orders its army to slaughter its people, there is no hope for this country,” she said.

“The Massacre haunts me, and haunts generations of Chinese people.” The little girl was inspired by watching on TV the white-shirted Tank Man who tried to stop the People’s Liberation Army’s tanks.

Photo credit: Derzsi Elekes Andor/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Derzsi Elekes Andor/WikiCommons/CC

Already doubtful of authority, Mou quickly found that the Chinese education system is designed to brainwash students. “We were always told by teachers that ‘American Imperialism never gives up on destroying us.’” She also recalled that in her high school, all students were compelled to watch China Central TV (CCTV) news every day. During diplomatic conflicts between the US and China, CCTV news’s inflammatory language always aroused students’ irrational hatred of America.

After high school, Mou could not stand her education any longer, so she decided not to go to university. Instead, self-taught, she became a freelance graphic and website designer, photographer, writer, and commentator.

Inspired by the Tank Man, Mou started to dedicate herself to human rights. She once created a website commemorating the Massacre, but it was soon shut down. In 2010, she joked on Twitter that she would carry a banner saying ‘Congratulations, Uncle Xiaobo!’ to the site of an anti-Japanese demonstration in Chongqing. Her joke, showing her support of a dissident, crossed the CCP’s red line. At midnight that day, she was taken to a police office, interrogated, and verbally humiliated for twenty hours. From then on, Mou was blacklisted, with police surveillance sometimes close and sometimes loose.

In 2013, Mou attended a speech given by the famous China scholar, Perry Link, in Hong Kong, where she met many Chinese democracy activists. They invited her to join the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), an NGO devoted to freedom of expression for people working in Chinese language and literature, and a member organization of PEN International. Through ICPC’s network, she was recommended to CRLW to help it with English translation, website maintenance, graphic design, and human rights research.

Research work for CRLW enabled Mou to get to know the developing Chinese human rights situation inside out. She shared her observations and analyses with New Bloom.

In May 2015, an unarmed petitioner, Xu Chunhe, was shot dead in front of his old mother and three children by the police at the Qing’an train station, in Heilongjiang Province. This incident drew public anger rapidly. More than twenty human rights lawyers and netizens who flocked to Heilongjiang to support the victims were detained by the police, which further aroused public rage and caused over 600 lawyers to launch an online petition to protest against the authority.

The Qing’an Shooting triggered the 709 Crackdown, the massive crackdown on lawyers and human rights activists across the whole of China, Mou said. “Since July 9, 2015, firstly, they targeted human rights lawyers; then they arrested those lawyers’ lawyers; step by step, they started targeting NGOs from 2016; it was Twitter users’ turn from 2017.” The police took more than 321 human rights defenders for interrogation, many of whom were detained, prosecuted, sentenced, and imprisoned.

CRLW could not escape the fate of persecution either. The detention of its founder and director, Liu Feiyue, in 2016 was followed in 2019 by a five-year imprisonment for “inciting state subversion”.

“I was terrified,” Mou recalled. “The police searched Liu’s house, and it was said that they took piles of documents, including our pay slips. Everybody was likely to be the next target.”

After Liu, CRLW’s editor Ding Lingjie was jailed for posting a video mocking Xi Jinping. Mou indicated that she had put a lot of effort into training Ding how to write news articles, but it was all to no avail once Ding was arrested. “Activists are an essential resource in the human rights field. Any activist being arrested is a huge loss,” Mou said.

Despite her fear, Mou continued with her work of compiling the monthly human rights cases reports. Furthermore, she took over CRLW’s daily operations, which originally were Liu’s duties. In early 2017 she replaced Liu as the head of CRLW.

Photo courtesy of Mou Yanxi

Photo courtesy of Mou Yanxi

“We had got busier and busier,” Mou said. The CRLW team focused on releasing statements and producing posters that allowed the voices of the targeted lawyers and NGOs to be heard. She emphasized that if the public has no clue about what’s happening and thus shows little attention to these activists, which means little pressure is put on the authorities, prisoners of conscience would have suffered even more severe punishments.

The massive numbers of arrests have led to a severe deterioration in judicial transparency. As lawyers, activists, and netizens have been suppressed, Mou pointed out that the flow of information has been almost cut off within civil society: “Information about lawsuits against rights activists has suddenly been much harder to access.” She indicated that, in the past, CRLW could acquire information such as the activists’ whereabouts and the progress of their lawsuits soon after they were arrested. However, over the last year she has found quite a few people who have already been released from prison, although there are no records of their cases in CRLW’s archives. “It was not until I saw their court’s judgments released last year that I discovered retrospectively that they had been arrested and sentenced to jail!”

Mou has witnessed the worsening of rights conditions in China. “In 2015, I documented, on average, 200-300 victims of rights violations per month. Nowadays, the number surpasses one thousand per month,” Mou said.

Mou, fortunately, escaped the mass arrests. A police officer came to investigate her connection with Liu Feiyue and CRLW, but ended up in vain. She began to consider going in exile, and an incident motivated her to make up her mind.

In 2018, Mou gained a Democracy and Human Rights Service Fellowship from Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD), an NGO sponsored by the Taiwanese government. She flew to Taiwan to research nonviolent struggle, in which she had always been interested, yet which is taboo in China.

The four-month research project put Mou at risk again. When she went back home to Chongqing in September 2018, she was immediately called to the police office for interrogation several times. “Surprisingly, they knew my research topic and the amount of money I received in sponsorship from TFD, which frightened me to death!” Mou recalled. She speculated that there might be a spy inside TFD who had leaked her information to the CCP.

To avoid trouble, Mou fabricated an excuse. “I told them that my aim in visiting Taiwan was simply to travel. Since TFD provided the opportunity and funding, they assigned me the topic of nonviolent struggle, and I had no right to say no,” she said.

During the investigation period, Mou did not know whether she had successfully deceived the police; so she decided to seek asylum abroad. “I turned off my mobile and took out the SIM card to avoid police surveillance. I hid in a friend’s place in Chengdu, and secretly met with officials from the US consulate and the Australian consulate in Chengdu,” Mou said. However, she was not granted asylum.

Half a month later, knowing from her father that no police had come for her, Mou returned home quietly.

Despite being safe temporarily, Mou found the police enhanced their monitoring of her. She mentioned that they installed cameras outside of her house. “They even tried to rent my neighbor’s house to keep an eye on me, but were rejected.”

Mou described her fear of the unknown: “That was my darkest time. Every day, I’m worried about whether I will be arrested. The only thing I can do is to keep writing monthly human rights case reports, and wait for them to come for me again.”

Photo credit: Mstyslav Chernov/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Mstyslav Chernov/WikiCommons/CC

Teng Biao, who also experienced a similar police scrutiny, used the term ‘High-Tech Totalitarianism’ to depict China’s current situation. He pointed out that the CCP combined traditional and digital surveillance over Chinese society, using technological tools such as the Social Credit System and health tracking platforms to invade people’s privacy. Under these circumstances, everyone, especially activists, are under almost total control.

“The CCP wants all dissidents and activists to lose their mobility so that all protests will be destroyed. It also aims to deter activists from engaging in activism by inconveniencing them,” Teng said.

The police came to Mou again in December 2018, not in order to arrest her, but in order to try and persuade her to provide intelligence about overseas NGOs. “I maintained close ties with overseas NGOs. If I cooperate with the police, I could have endangered NGO networks. I turned them down,” Mou said. The police officers continued to chat in mild tones, asking her to spy for the authorities.

Unexpectedly, through this conversation, Mou found the police officers’ blind spots and took advantage of them.

“I sidetracked them and found that they were highly interested in taking out insurance policies in Hong Kong,” Mou indicated. “They are normal people who have children. And they know insurance products in mainland China are a fraud, so they want to move assets to Hong Kong.”

Afterwards, she said, the absurd thing was that she was forced by the police to accept a meal in a restaurant, where a crowd of officers flocked around to ask about the process of taking out insurance in Hong Kong.

“Although the close surveillance continued, the tensions between me and the police seemed eased. I was safe again.”

Still afraid of crackdowns some day, Mou kept planning to flee. In 2019, she was granted a place on a fellowship scheme by a British academic institution. She seized the opportunity without hesitation. After settling down, she is now applying for political asylum in the UK.

“I find it hard to see myself as a human rights defender. I always say that I am a human rights researcher, because I couldn’t defend anything when I was in China,” Mou said in an online event on Human Rights Day on December 10, 2020, which was her first public appearance as an exiled activist since leaving China.

What’s next for Mou? “I will reveal the true human rights conditions in China to English speakers,” Mou told New Bloom. “I have a responsibility.” She plans to translate more human rights-related Chinese articles into English.

Photo courtesy of Mou Yanxi

Photo courtesy of Mou Yanxi

International society has become gradually aware of the CCP’s persecution of minorities such as Uyghurs and Tibetans. Mou points out, however, that it’s not widely known that there is little difference between the treatment of these groups and that of the majority of the Chinese people.

Mou believes, through the case of Hong Kong, where human rights and political freedoms have experienced a severe downturn in past years, that it is clear that the CCP is the enemy of democracy.

“It’s a worldwide crisis. They will devastate democracy and freedom all over the world,” she contends.