by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Brian19891003/WikiCommons/CC

THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT sentenced citizen journalist Zhang Zhan to four years in jail late last month. Zhang has been detained since May. According to Zhang’s lawyer, Zhang has been on hunger strike since June against her charges. Nevertheless, Zhang is currently forcibly force-fed through a feeding tube, while her hands are handcuffed twenty-fours a day in order to prevent her from removing the tube.

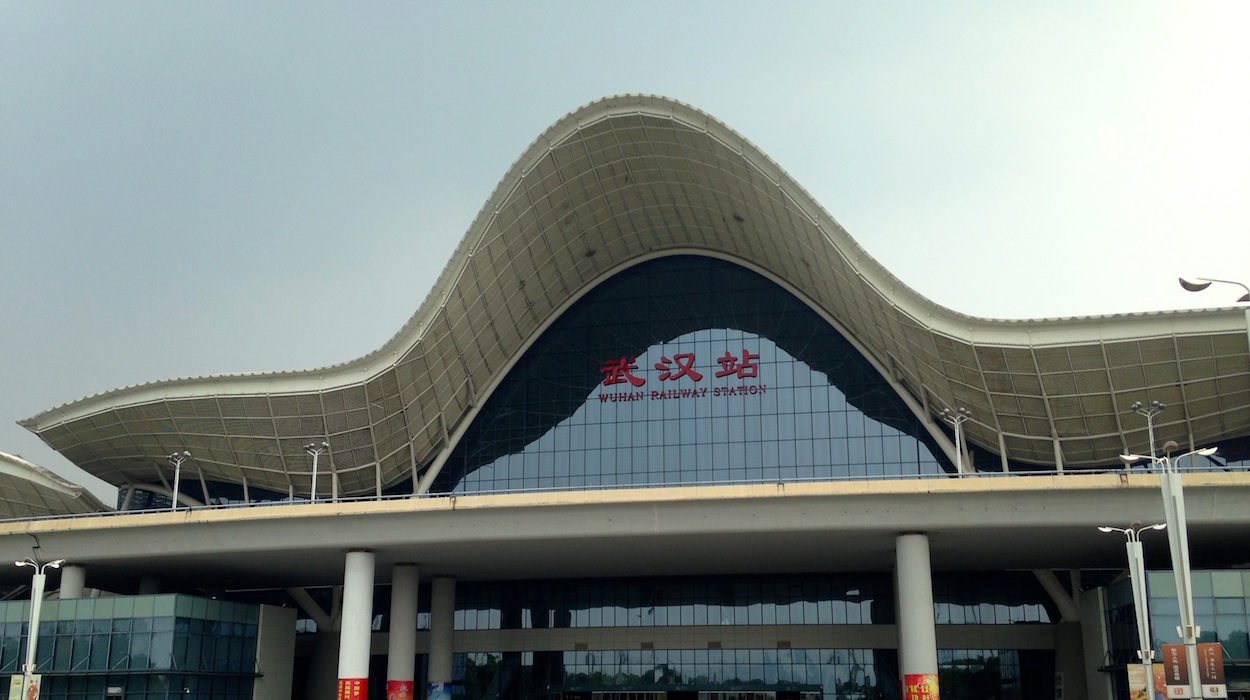

Originally a lawyer based in Shanghai, Zhang reported on the initial COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan earlier this year, beginning her coverage in early February. Zhang’s reporting went counter to the Chinese government’s narrative at the time, depicting the Chinese government response as less than effective, showing hospitals in Wuhan as overburdened by the early stages of the pandemic. Zhang was critical of the Chinese government’s response in her reporting, such as by openly questioning whether forced lockdowns were necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Photo credit: Soramimi/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Soramimi/WikiCommons/CC

Zhang is not the only citizen journalist to be arrested in connection with independent reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Other citizen journalists that have been detained or otherwise ceased contact with the public include fellow lawyer Chen Qiushi, who is believed to be under surveillance by Chinese authorities and incommunicado, Fang Bin, who disappeared after posting videos from Wuhan in February, and Li Zehua, who disappeared for two months before reappearing in April to state that he had forcibly been quarantined by the government.

However, Zhang is thought to be the first Chinese citizen journalist to face charges related to the COVID-19. Zhang is accused of having spread false information about the COVID-19 pandemic on the Internet and on social media, as well as faces charges of “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble”—a legal charge frequently used against critics of the government in China. Zhang’s sentencing occurred in the same timeframe as the one-year anniversary of the first reports of COVID-19 last year.

Authorities have particularly honed in on interviews that Zhang gave to the Epoch Times and Radio Free Asia, perhaps hoping to depict Zhang as collaborating with foreign forces to undermine China’s image. In past months, the Chinese government has sought to juxtapose the comparative stability of the present situation in China with that of western countries, to rewrite the early narrative of the COVID-19 pandemic so as to depict the Chinese government as having had the pandemic under control from its start, and to suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic may not have begun in China. More broadly, authoritarian regimes the world over have sought to centralize the distribution of information about COVID-19 in order to depict themselves in a more positive light.

Zhang’s sentencing took place in the same timeframe as the sentencing of ten of twelve Hongkongers that tried to flee to Taiwan by speedboat in August, before being intercepted by the Chinese coast guard. Two of the twelve, Tang Kai-yin and Quinn Moon, faced charges for organizing the attempted border crossing that could have resulted in up to seven years imprisonment. The other ten faced up to a year in jail on charges of secretly attempting to cross the border. Of the twelve, the youngest was sixteen and the oldest thirty-three. Family members of the twelve report receiving letters from the twelve that they seem to have been forced to write, due to their being unusually written.

Among the twelve were individuals that face charges under the national security law targeting Hong Kong that was passed in June by China’s National People’s Congress, which could result in lifetime in jail. The “Hong Kong Twelve” were detained in Shenzhen, were denied communication with Chinese lawyers hired by their family members, and were only informed of their trial date on Friday. International media was blocked from reporting on the trial. Family members called for there to be a public trial, while international human rights organizations raised the possibility that the twelve could be secretly tried behind closed doors.

Eventually, the trial resulted in sentences between seven months and three years in jail for most members of the Hong Kong twelve, while the two youngest members of the Hong Kong twelve—both under eighteen—were transferred to the custody of the Hong Kong police, who will likely still charge them. Tang and Moon received the heaviest sentences, with Tang sentenced to three years in jail and a 20,000 RMB fine and Moon sentenced to two years in jail and a 15,000 RMB fine.

Agnes Chow. Photo credit: Honcques Laus/Flickr/CC

Agnes Chow. Photo credit: Honcques Laus/Flickr/CC

It is thought that the sentence of Zhang Zhan and of ten of the Hong Kong Twelve took place during the winter holidays, in order to minimize western press coverage of the trial. This is not the first time that such tactics have been adopted by the Chinese government.

To this extent, it is possible that the Chinese government will expand the scope of its arrests. Apart from arrests in Hong Kong directed at pro-democracy activists and politicians including Joshua Wong and a number of former pan-Democratic legislators, recent editorials in the People’s Daily have called for Apple Daily owner Jimmy Lai’s deportation to China to face charges after the Hong Kong High Court released Lai on bail, claiming that Lai was dangerous. In the wake of this backlash, Lai’s release on bail was later overturned and Lai was jailed again. Agnes Chow, another prominent youth activist and former Demosisto member, was also transferred to maximum security prison at the end of the December. Chinese reporters working for western media outlets, too, have come under scrutiny, such as with the detention of Bloomberg journalist Haze Fan earlier in the month. The crackdown continues, then.