by Enbion Micah Aan

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Henri Cartier-Bresson: China

“A CAREER WITH five great photographs would be pretty good…” said Richard Avedon, “…[Henri Cartier-Bresson has] hundreds of them!”. This emphatic statement is not an exaggeration, as Cartier-Bresson is easily one of the greatest photographers of his generation, and one of the great artists of the twentieth century. It is quite a privilege to walk through the galleries of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and be in the presence of the great master’s work.

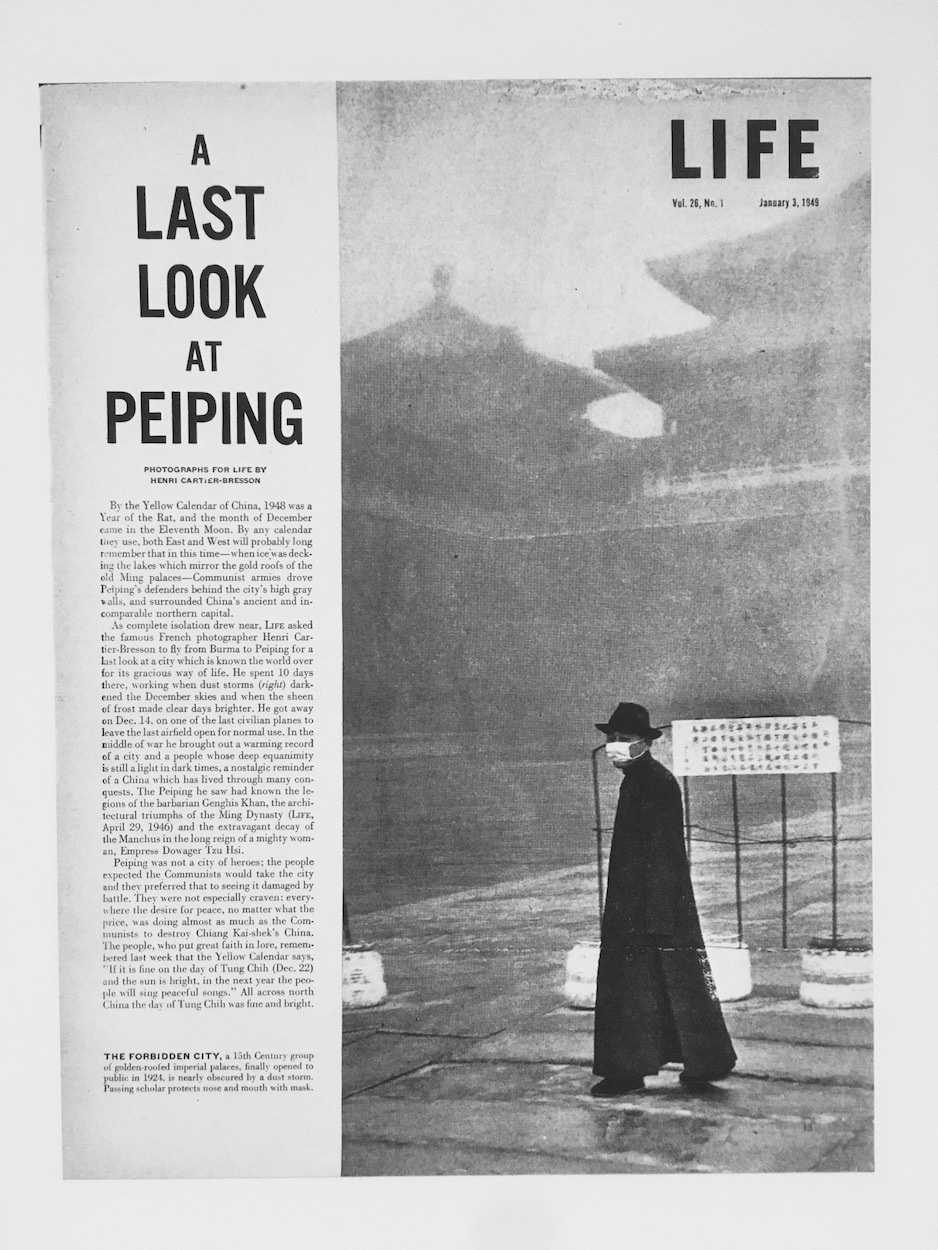

The exhibition includes two periods of Cartier Bresson’s work in China. He photographed during the expectant takeover of the Chinese Communist Party during 1948-1949 and then 10 years after the takeover in 1958. In 1948, Cartier-Bresson received a commission from Life Magazine to photograph the “last days of Peking”. The assignment was supposed to be for two weeks, but he ended up staying for ten months. As the exhibition shows, his subject matter is quite diverse, covering refugees, banking crises, scenes in restaurants, a religious pilgrimage, and many other topics. Cartier-Bresson was, at the time, already a well-established photographer, having had a retrospective in the Museum of Modern Art in 1947 and founded the Magnum Photo Agency with Robert Capa and David Seymour in the same year.

As anyone with any degree of familiarity with Cartier-Bresson would expect, all the photographs in the exhibition were excellent. Every photograph is impeccably composed, taken at the ephemeral and perfect “decisive moment”. Unlike most photographs we encounter daily, Cartier-Bresson’s photographs feel very much alive because the timing of when the picture is taken is so perfect—one second earlier or later, the quality of the scene would be completely different. The strongest and most famous of Cartier-Bresson’s works tend to be ordinary scenes that he was able to impart with beauty. For example, a bicycle rushing by can become such a visual pleasure that it creates a lasting aesthetic moment. The perfect moments and compositions Cartier-Bresson captures feel very fragile and incredibly precious. In The Decisive Moment, an accompanying 1973 short film in the exhibition, Cartier-Bresson noted the challenge of photography is timing, as “life is once, and forever”. Looking at all these photographs is certainly a thrilling experience for anyone who is interested in the art and craft of photography.

As aesthetically pleasing as Cartier-Bresson’s work is, we must also examine the work in its historical and political context, and under this light, unfortunately, the content of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs was not quite on par with its aesthetics. We can start by looking at the most well-known photograph in the exhibition, which is the photograph one would see walking into the gallery. Let’s first look at the photograph, as a gallery visitor would, without prejudice, and without context at the entrance. What does this picture look like, feel like? Does it not eerily resemble a dance company’s arrangement? All the gestures and movements work in concert in creating an arresting image like this one. However, this is a picture of desperate people trying to purchase gold after many failed KMT monetary policies—this picture, while beautiful, does not do enough to capture the fear and economic anxiety of the masses at the moment. Instead, the crowd looks as if they are posing for a beautiful photograph under the direction of a dance choreographer.

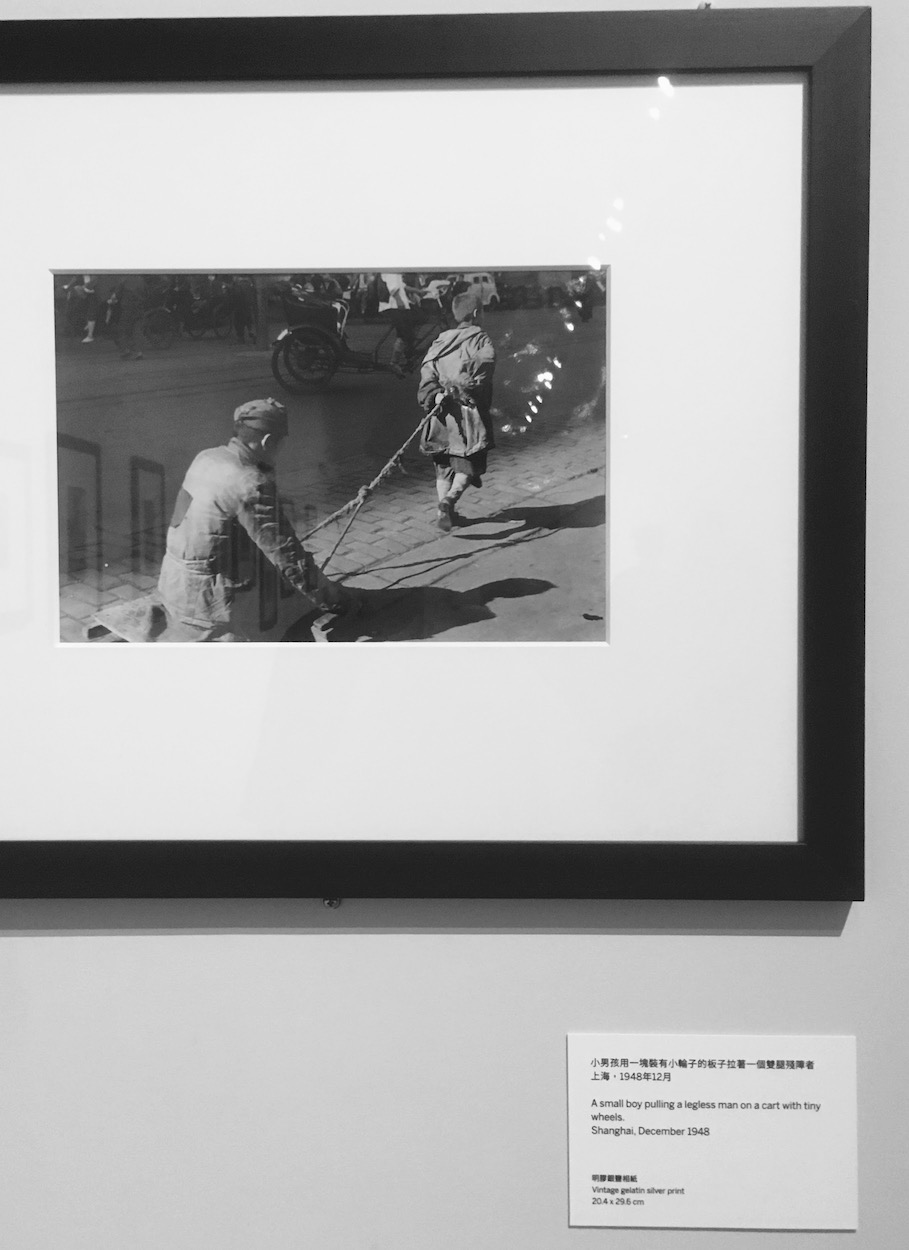

Now to illustrate the point further, I’d like to point out two more pictures. One is of a blind man with two kids, one of whom he keeps on a leash, and the other one is of a legless man being pulled by a child. Once again, in these two examples, Cartier-Bresson failed to depict these scenes accurately in terms of the subjects’ psychology or to reflect the plight of the unfortunate. Both pictures sacrificed elements of truth for elements of aesthetics.

The father holding a basket on the right and a child on the left—the gesture Cartier-Bresson captures here maximizes the compositional possibility of the photograph. While the facial expression of the father looks tense, the photograph still lacks in its emotional impact. The photograph of the legless man and the child remain faceless and therefore emotionless because it is taken from their backs, most likely for the great lighting and composition.

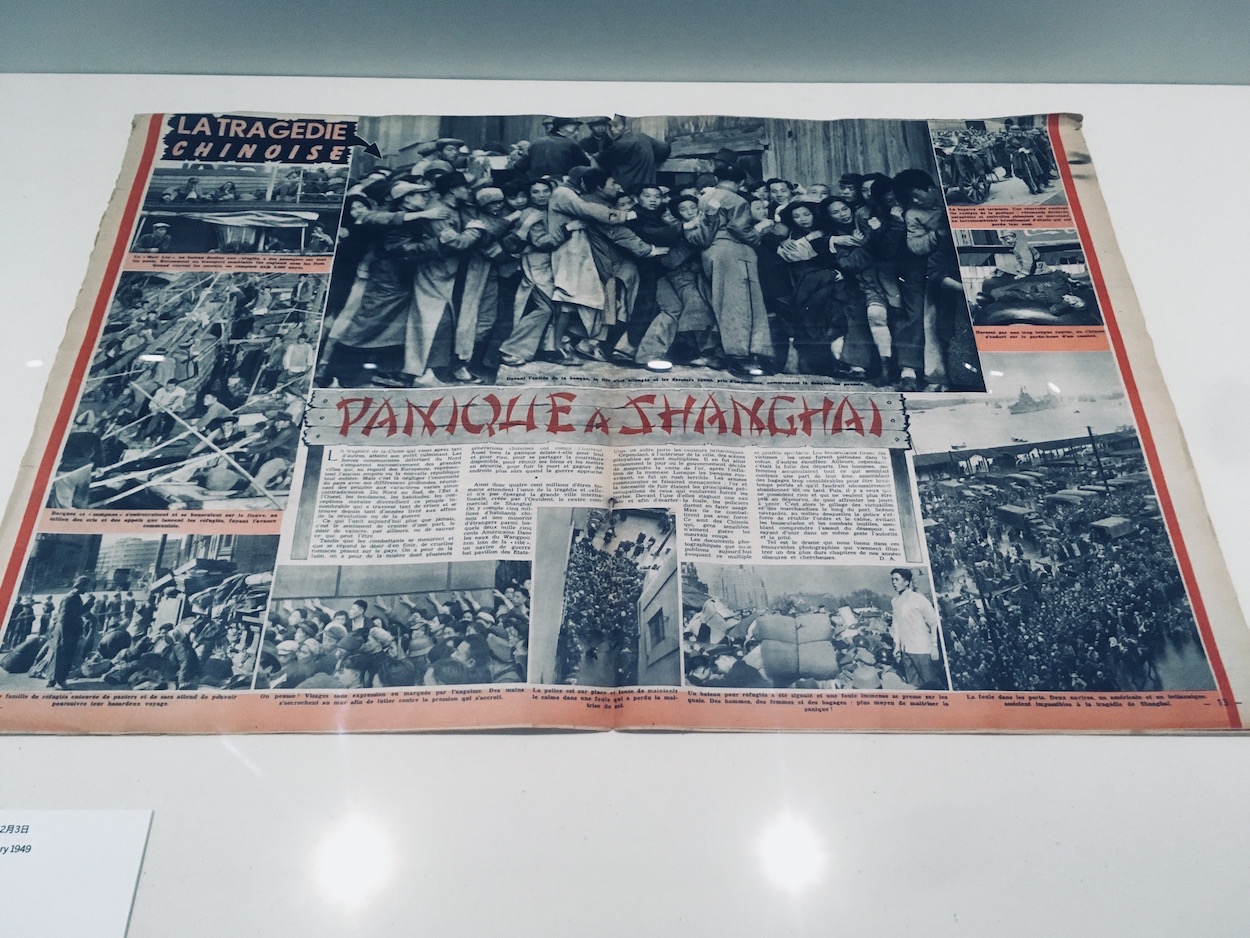

One could say I’m merely “cherry-picking” photographs, but the fact that political opposites could both use Cartier-Bresson’s work as propaganda also speaks volumes. The Life Magazine, in fact, used the pictures as anti-communist sentiments, and one can also easily see how the CCP used his pictures, particularly from 1958 onward, as propaganda. In fact, these pictures can also easily be used to exoticize Chinese people, as seen under the “Panique a Shanghai” article.

Throughout Cartier-Bresson’s career, he consistently made some of the most delightful and beautiful photographs, but when it comes to social and historical context, aesthetics seem consistently to still be his primary focus. One does not need to look further than Walker Evans, whom Bresson had an exhibition with in 1935. Evan’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men allows us to see finer examples of documenting a historical moment. This is not, of course, to say that Cartier-Bresson’s work are not masterpieces—they certainly are great examples of how beautiful photography can be, but there is a certain limitation to his style of photography.

What is frustrating about the lack of a political point of view in Cartier-Bresson’s work is also that he himself was a leftist. He worked for Ce Soir, a communist newspaper, in 1937, and his relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre was actually quite close—close enough for Sartre to write a preface for Cartier-Bresson’s book. In fact, Cartier-Bresson’s reputation as a Marxist was well established enough that the CCP was comfortable in allowing him to photograph in 1958. In other words, Cartier-Bresson, himself, unlike what his pictures would suggest, was actually very politically and intellectually aware. However, his political understanding seems to be buried under the weight of his own talent for aesthetics. Cartier-Bresson himself would say so much about the genre of documentary photography in the aforementioned short film:

“I’m not interested in documenting. Documenting is extremely dull in journalism… I am a very bad reporter and photojournalist… I’m not a reporter. [Reportage is done] accidentally…on the side…. [I] try, and concretize a situation, which at one glance has everything and which has strong relations of shapes…which for me is essential, for me it’s a visual pleasure. It’s a rhythm the way the head falls here. This goes back. There is a rhyme between different elements. There’s a square, a rectangle, another rectangle. It’s all these problems which I’m preoccupied with. The greatest joy for me is geometry…”

Cartier-Bresson’s artistic background was in surrealism, and Robert Capa’s sage advice for him was to shoot whatever and however, he’d like but not to be labeled as a “Surrealist Photographer.” Therefore, to receive assignments, Cartier-Bresson played the role of a photojournalist while actually shooting more like an art photographer. This partly explains why Cartier-Bresson’s work, while immensely aesthetic, seems to lack substance in the historical or political sense. Avedon was right in saying that “we are all Cartier-Bresson’s babies”, as his photographs were and will always be influential, as long as photography is practiced as an art form. However, this overt reliance on aesthetics would be rejected by the next generation of great photographers, as pointed out by the New York Times in the Robert Frank obituary:

“Frank would later reject Cartier-Bresson’s work, saying it represented all that was glib and insubstantial about photojournalism. He believed that photojournalism oversimplified the world, mimicking, as he put it, ‘those goddamned stories with a beginning and an end.’”

Frank, in his reaction to the Life Magazine aesthetics, would make what many would consider to be the greatest photography book of all time.

Finally, we should also look at the role of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. Any time a museum can exhibit a large body of work from a great artist such as Cartier-Bresson, it is a success. I enjoyed my time looking at these photographs very much and would recommend everyone to attend, but it is surprising that there is a complete lack of Taiwanese perspective in this exhibition. Regardless of how Cartier-Bresson succeeds or fails in capturing the sentiment at the time, the history captured here is intimately connected to Taiwan’s own history. Many of the subjects would be ancestors of contemporary Taiwanese people, as many of the refugees would end up coming to Taiwan. Wouldn’t it be nice if the museum could have offered some commentary from a Taiwanese perspective?