by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Presidential Office/Public Domain

AS WITH THE death of any major political figure, one of the consequences of Lee Teng-hui’s death has been that political figures of all persuasions have rushed to praise Lee. This has been ironic, in many ways.

It may not be surprising that members of the DPP and pan-Green camp have been among those praising Lee, seeing as Lee came to be seen as a figure supportive of Taiwanese sovereignty and, in fact, of Taiwanese independence in the past two decades. Yet this is in itself something of a historical reversal.

Lee Teng-hui (left) meeting with current president Tsai Ing-wen (right). Photo credit: Presidential Office/Public Domain

Lee Teng-hui (left) meeting with current president Tsai Ing-wen (right). Photo credit: Presidential Office/Public Domain

As president of the ROC from 1988 to 2000 and chair of the KMT up until 2000, Lee was actually the KMT president that held power during the outbreak of 1990 Wild Lily Movement. Lee ran against the DPP candidate, Peng Ming-min, in 1996. Lee becoming Taiwan’s first democratically elected president in the course of Taiwan’s first direct presidential election was actually through defeating the first DPP presidential candidate.

Accusations that Lee was secretly a supporter of Taiwanese independence dogged him throughout his presidency, and after Lee left office, he became more open about support for Taiwanese sovereignty. It is also true that early leaders of the DPP, such as Hsu Hsin-liang, included former KMT politicians that unexpectedly turned on the KMT after working their way up to positions of power. Other early DPP leaders, such as Shih Ming-teh, later shifted allegiances to the pan-Blue camp, despite facing years of imprisonment at the hands of the KMT.

Members of the KMT have offered condolences for Lee as well, praising Lee in rather general terms by claiming that he was a president that always stood for the people. Former president Ma Ying-jeou, who lashed out at Lee on a number of occasions in the past decade for Lee’s fondness for Japan, stated that he respected Lee, despite Lee’s political views changing drastically after he left office.

This, too, is ironic. In the past decades, the KMT feared a second coming of Lee Teng-hui as a potentially existential threat, fearing that party members—particularly benshengren—could unexpectedly prove to be political turncoats. This has proved an obstacle to efforts to reform the KMT to change the party’s pro-China image, with would-be-reformers accused of being infected by pro-independence ideology in the same way as Lee.

KMT views of Lee have been conspiratorial enough that some members of the KMT even attributed major events during the Sunflower Movement to Lee’s intervention, seeing Lee as responsible for the mobilization by the pan-Green camp in support of the movement. In this light, with abortive efforts to reform the party having stalled and the party now leaning heavily into partisan mudslinging, the KMT will probably not take any lessons away from Lee’s death. The KMT may simply be even warier of internal threats such as Lee after his death.

In truth, Lee’s political views are hard to pin down. Lee associated with individuals that later became dangwai intellectuals while younger, but then spent years within the KMT. Some anecdotal stories claim that as part of the KMT, Lee was open about his pro-localization views, even as publicly he towed the official line.

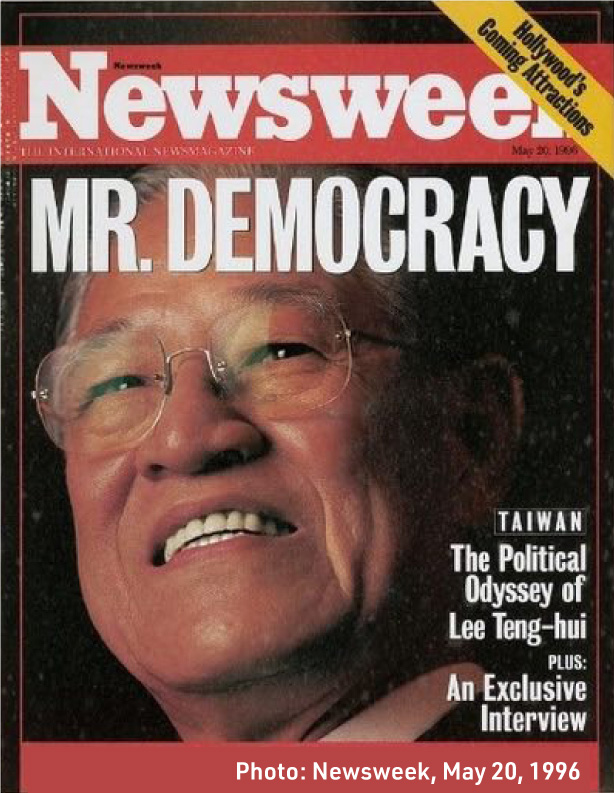

1996 Newsweek cover featuring Lee

1996 Newsweek cover featuring Lee

Were Lee’s views always pro-independence, as his proponents often claim, and just that he closeted them for years in the KMT in order to work his way to political power? Did they, in fact, change over time? Did Lee go along with changes in political fortunes over time in order to continue to be politically relevant, or did he always retain views critical of the KMT during his decades in the party?

Certainly, Lee was no saint, something which the sanctified depiction of Lee by the contemporary pan-Green camp will avoid. As is a broader issue facing the pan-Green camp writ large, given its romanticization of the Japanese colonial period in juxtaposition to the KMT’s authoritarian rule, Lee could be seen as an apologist for the actions of the Japanese empire, even visiting Yasukuni Shrine in 2007. It is also well-documented that Lee had close ties to organized crime, relying on organized crime as a means to mobilize votes and field candidates because he could not control the KMT intelligence apparatus to mobilize votes for him.

However, it is likely that it is too early for critical evaluations of Lee, given sharp political divides and irreconcilable historical points of view regarding the past three decades of Taiwan’s democratization between the pan-Blue and pan-Green camps. As such, even if one expects both political camps to praise Lee Teng-hui’s life, in reality, views regarding Lee will continue to be sharply polarized in Taiwan.