by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Studio Incendo/Flickr/CC

A NEW GENERATION of “tankies” has emerged, particularly on Twitter and other online spaces. Many are people of the Asian, and particularly Chinese, diaspora in Anglophone contexts. Fundamentally, this diasporic Chinese nationalism offers very little that is new, instead reiterating an old set of ideas that has persisted for decades among tankies—that is, leftists who back authoritarian regimes in the belief that they present an alternative to western capitalist nations.

This may be a symptom of the times. With resurgent interest in the political Left in the past few years, as the result of the global economic downturn and the right-wing lurch of many countries, an increasing number of young people have become politically radical. Elevated tensions between the US and the PRC have left members of the Chinese diaspora searching for politically radical responses to rapidly changing conditions, including rising xenophobia against people of East Asian descent.

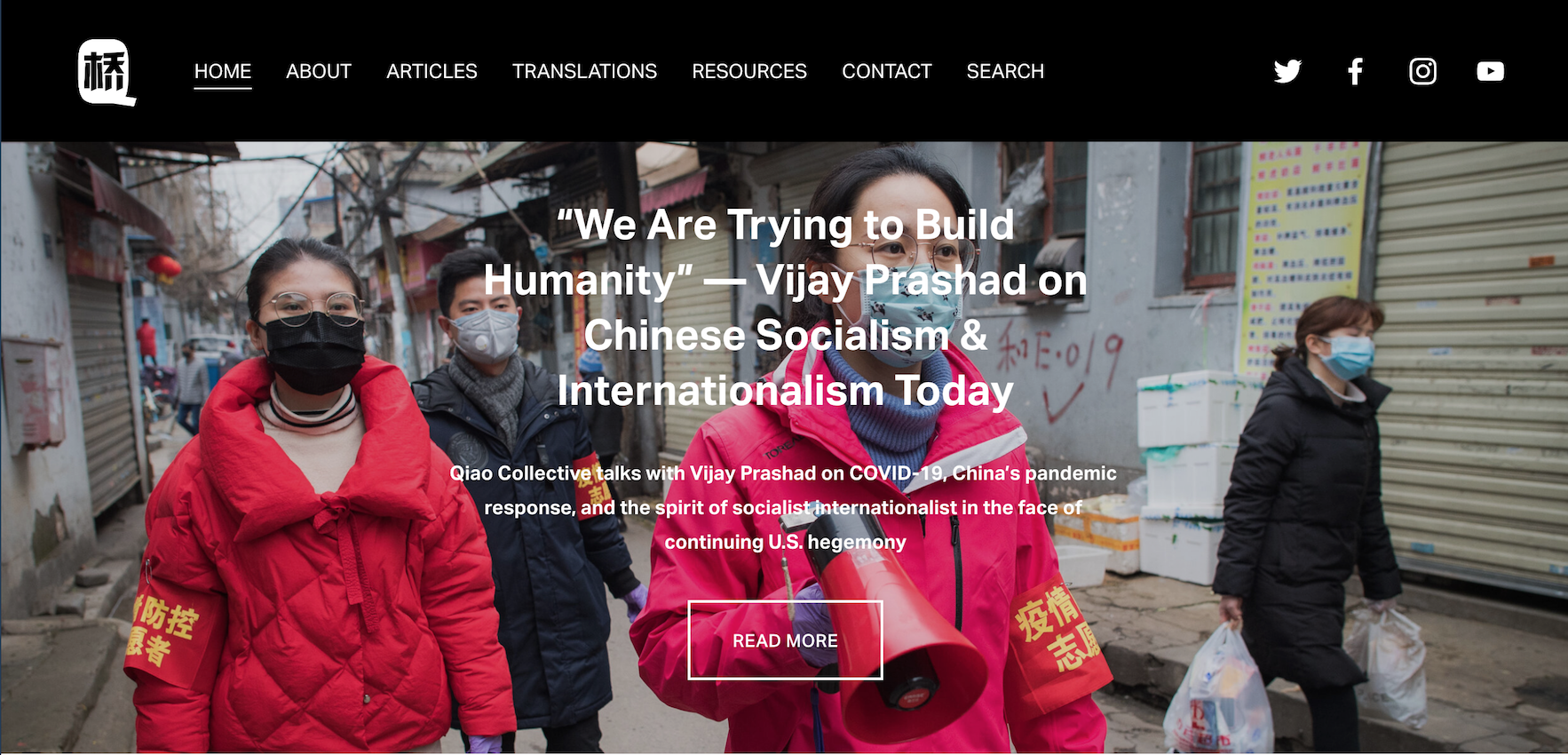

The front page of the Qiao Collective’s website

The front page of the Qiao Collective’s website

One of these responses is to embrace a diasporic Chinese nationalism that sees itself in primarily leftist terms. For example, the rise of the Qiao Collective has been one of the inadvertent effects of the Hong Kong protests over the past year. Though it began as a personal Twitter account, Qiao seems to have been formed in reaction to the Lausan Collective—which formed last year with the aim of providing decolonial leftist perspectives on Hong Kong after the start of the Anti-ELAB protests—and the international Left’s increased interest in events in Hong Kong. Qiao likely formed because it viewed Lausan as a threat that could attract support from the international Left in solidarity with the self-determination struggle in Hong Kong.

We might take Qiao as one telling symptom of a broader phenomenon. In just a few short months, Qiao rapidly gained close to 15,000 followers on Twitter and the support of leftist intellectual figures such as Vijay Prashad and Nick Estes. The growth of Qiao seems to have come primarily from a savvy Twitter presence; Qiao only has a handful of articles on their website and otherwise has primarily offered webinars. Qiao recently had its Twitter account suspended, alleging on Facebook that Hongkongers led a campaign to mass report their account. While not impossible, little evidence substantiates such a claim.

Very little of Qiao’s thought is creative or new, instead primarily consisting of warmed-over tankie thought. The term “tankie” originated as a term for leftists that uncritically supported the Soviet Union, despite the willingness of the Soviet Union to violently repress popular uprisings such as the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Decades have passed, yet tankies have hardly changed, continuing to uncritically back authoritarian governments that they view to be socialist, downplaying any domestic repression of political dissidence and claiming that these countries outstrip capitalist nation-states in economic productivity.

How tankies conceptualize the nation-states and political regimes that they view as authentically socialist has seen very little change over past decades. Ultimately, the origin of this conceptualization of the world originates from a Cold War framework in which the political options available to radicals are conceived narrowly in campist terms: aligning with one geopolitical bloc against another.

Yet what proves interesting about Qiao as a phenomenon is how it arose out of anxiety that global sympathy for Hong Kong’s self-determination struggle could organize the Chinese diaspora in a manner critical of the Chinese state. This is why it may be worth examining Qiao’s thought at present, seeing as one expects rising xenophobia and increasing tensions between America and China to continue to push some toward embracing a form of diasporic statist Chinese nationalism.

Idealization of the People’s Republic of China

FOR QIAO the PRC is and has always been a communist country. Qiao rejects the view that China experienced any sort of capitalist turn following Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms in the 1980s, a view that even many Chinese leftist nationalists do not hold. Nor does Qiao accept the argument that China was never socialist or communist and always state capitalist, even during the Mao period, as some argue.

Instead, Qiao claims that China “innovated the socialist market economy” through employment of the “bird cage economy”, in order to “accumulate capital [and] alleviate China’s extreme poverty in order to achieve socialism”. The term “bird cage economy” comes from Chen Yun, an economic advisor of Deng Xiaoping, though Qiao does not elaborate in any detailed manner on their understanding of what this means.

Westerners falsely think of Deng’s marketization as a deviation from Mao or Xi’s socialist policies when actually, China innovated the socialist market economy (also called bird cage economy) to accumulate capital & alleviate China’s extreme poverty in order to achieve socialism.

— Qiao Collective (@qiaocollective) May 8, 2020

One will scarcely find any recognition of China as one of the world’s most unequal societies—not in the work of Qiao, which demonstrates a complete disregard for the rising number of workers’ struggles in China in recent years, whether that is the Shenzhen Jasic struggle or other similar events, or unionization efforts among delivery workers, tech workers, and workers in other sectors. While possibly primarily meant for Anglophone consumption, Qiao’s public reading lists contain very few Chinese-language sources, raising questions as to how connected Qiao members are to on-the-ground realities in China—though this disconnect is a risk perhaps always faced by diasporic projects.

Qiao’s assertion that China is and has always been a socialist country follows rather common tropes. For example, Qiao celebrates the Chinese government’s efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic in economically productivist terms, given actions by the state to increase medical production, build hospitals, and carry out mass testing of patients. This is touted as the means by which “Chinese socialism” has successfully fought off COVID-19.

In truth, China’s successes fighting off COVID-19 are hardly attributable to its socioeconomic model. Across the Taiwan Strait, in indisputably capitalist Taiwan, the Taiwanese government has prevented the spread of COVID-19 through similar measures to ramp up production of needed medical supplies by the state working with private industry, carrying out quarantine measures, and contact tracing.

State intervention into the private industry proves hardly unique to “Chinese socialism”, but is simply what effectively administered states—which, unlike the US, do not have an irrational reluctance to intervene when needed into the free market—have done to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Other capitalist states which have been successful keeping the number of COVID-19 cases low have carried out similar actions, as has Vietnam, another nominally socialist state; it is hardly that the Chinese state is unique in its response to COVID-19 because of the secret sauce of “Chinese socialism”.

Yet asserting the superiority of a socialist model in productivist terms is nothing new. Leftist idealization of the Soviet Union before its collapse drew on similar tropes, touting the superiority of Soviet socialism over American capitalism, with the claim that socialist states’ productive capacities in manufacturing far exceeded those of western capitalist states. So, too, with Qiao’s celebrations of Cuban or Venezuelan socialism.

This is one of many ways in which Qiao’s thought reflects long-standing ideological projections onto “actually existing socialism” from western leftists onto non-western contexts. But this also gestures toward Qiao’s positionality as Chinese diaspora, whose political understanding of China is primarily determined in reaction to the western political context in which Qiao members live. Qiao’s view of the PRC seems rooted in a desire to uphold an idealized China as a utopian alternative to the West, rather than engage with the messy reality and many contradictions of contemporary China.

Qiao’s Contradictory Logic Between the West and China

IT COMES AS no surprise, then, that Qiao willfully ignores domestic repression of political dissidents in China, along with almost anything that reflects on China in a negative light, including the behavior of Chinese citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Qiao’s narrative, “mutual aid” was the only response to COVID-19 from Chinese citizens, ignoring how people from heavily affected areas such as the province of Hubei or city of Wenzhou faced discrimination from other Chinese citizens, even being forcibly confined to their homes in some cases.

Photo credit: Studio Incendo/Flickr/CC

Photo credit: Studio Incendo/Flickr/CC

Qiao ignores initial efforts to cover up the COVID-19 pandemic by Chinese authorities. Qiao celebrates Li Wenliang—the doctor that originally sought to raise the alarm about the pandemic, then contracted COVID-19 himself and eventually died of it—as having been a loyal party member until death. This follows the narrative of Chinese state-run media, which has co-opted the story of Li’s death in order to prevent it from becoming a vehicle for political anger against the government.

Yet Qiao’s rose-tinted lens on political repression by the Chinese state is indicative of a key underlying characteristic of its thought. In the eyes of Qiao members, China is simply different—exterior to, and unable to be judged, on the same standards as the capitalist world.

Nowhere is this double-standard clearer than in Qiao’s attitude toward police in the US versus police in Hong Kong—which, for them, is China. Despite the Hong Kong Police Force routinely targeting demonstrators, including schoolchildren and the elderly, with tear gas, vicious beatings, and sexual assault, Qiao views such violent acts as wholly justified in putting down Hong Kong protesters, downplays the level of violence which has occurred, and claims that it is Hong Kong protesters who have been more violent than police.

▪️China has never called for sending in the military or shooting protestors.

▪️The Hong Kong police has never killed a protestor despite over a year of protestors beating & lighting civilians on fire and murdering a manYou know which country *has* done all these things? The US.

— Qiao Collective (@qiaocollective) May 29, 2020

For Qiao, this is because Hong Kong protesters are seen as monolithic agents of western imperialism. For Qiao, some demonstrators appealing to the Trump administration does not represent naivete regarding the realities of American imperialism or that some protesters in Hong Kong may be of a political rightward persuasion. Instead, it necessarily means that all protesters in Hong Kong have received funding and training from the CIA— including bizarre attempts to imply that protesters in Hong Kong have gas masks and body armor only because of funding from the American state, rather than the far simpler explanation that protesters simply purchased such equipment on their own.

Just a reminder to everyone scolding the Black Lives Matter protestors to learn from Hong Kong protestors, the only reason the HK protests are so well-resourced is because they are backed by, serve the interests of, & have received $29 million from the US.https://t.co/xQU6nU6xDo

— Qiao Collective (@qiaocollective) June 1, 2020

By contrast, Qiao roundly condemns police brutality when it takes place in the US. One notes Qiao’s strong reactions against the police killing of George Floyd, which it criticized as the result of deep-seated racism in American society—and rightly so. And Qiao also sees the protests by the Black Lives Matter movement as organic expressions of outrage, rather than accusing them of being the product of some conspiratorial state-orchestrated effort at regime change—as it claims of Hong Kong.

There is some irony in the parallels with American Republicans, who have expressed support for the Hong Kong protests and have condemned the actions of the Hong Kong Police Force, while proving utterly blind to police violence in America itself. In some cases, American Republicans have even accused Black Lives Matter of being a Chinese plot against the US. Likewise, Qiao supports Black Lives Matter while viewing protests in Hong Kong as being an American plot against China. Qiao inverts this logic of “outside influence”; yet Qiao shares with the American Right this statist denial of agency to people involved in protests that it disapproves of, with the view that rival state actors must be behind them.

More generally, while Qiao seems utterly in denial of police violence in Hong Kong and China—including against Black or minority populations—it is, on the other hand, highly critical of police violence in America against such groups. Earlier this year, Qiao denied that the forcible eviction of African migrant workers from their homes by Chinese police in Guangzhou took place, claiming that this was the work of capitalist landlords and business owners, then later insisting that authorities had punished those involved despite that Chinese police were involved in carrying out the evictions. Qiao generally refuses to acknowledge that the Chinese government itself carries out highly racialized policing practices in China.

Photo credit: Studio Incendo/Flickr/CC

Photo credit: Studio Incendo/Flickr/CC

It should be unsurprising, then, that one will find zero mention of the vast detention camps for Uyghurs in Xinjiang in the writing of Qiao, with it currently believed that upwards of one million Uyghurs are currently detained. The existence of such camps is dismissed as simply the propaganda of western governments. Funnily enough, despite Qiao’s apparent skepticism of western media outlets, as simply being vehicles for western imperialist governments to disseminate propaganda, Qiao itself seems to consistently take the word of Chinese state media outlets at face value. Chinese authorities themselves have acknowledged the existence of such camps since October 2018, backtracking on their previous denials. These camps have been justified on the basis of claims that Uyghurs are dangerous terrorists in need of political reeducation—requiring measures to prevent Xinjiang from becoming “China’s Libya” or “China’s Syria”, according to the state-run Global Times.

With its dismissal of the mass detention of Uyghurs as western propaganda, one notes that Qiao seems to have deeply internalized how Han Chinese are a minority in western contexts, then applied this view of Han Chinese in western contexts to China, viewing China as something like a subaltern nation-state. This ignores that Han Chinese are the majority in China and that, consequently, they have proved to be oppressors of minority groups—not unlike in the US, regarding how its domestic policing practices are in the service of white supremacy. It is, in fact, the same policing and surveillance technologies that circulate between Xinjiang and western-backed surveillance regimes from Ferguson to Gaza.

But while turning a blind eye to the blatant racism of the Chinese state, Qiao goes so far as to insist that Hong Kong and Taiwan, in fact, only reject China because of “racism” against Chinese. Putting aside questions about this choice of terminology—since the majority of the residents of Hong Kong and Taiwan are, like the majority of the residents of China, also of Han descent—Qiao shrugs off any concerns about one’s loss of democratic freedoms and freedoms of speech, or that people in Hong Kong and Taiwan may simply fear being subject to the arbitrary whims of an authoritarian regime.

Qiao’s use of the charge of racism is, in effect, oftentimes an accusation thrown at any critics of the PRC—never mind that the Chinese state can be seen as a Han ethno-nationalist one, given its actions against Uyghurs and other minority groups in China.

A Failure to Note the Political Convergence of American and Chinese Empire

ONE OBSERVES convergent political behavior between the world’s two superpowers, the United States and China. Apart from large domestic carceral populations and an increasingly brutal domestic police state, both seek to expand their global influence through coercive means. Yet both usually claim that coercive and exploitative foreign police is altruistic munificence, as in American claims that it is engaged in efforts to spread democracy globally, or the Chinese government’s claims that it is seeking to build “south-south cooperation” between nations of the global south.

Qiao takes at face value the claim that Chinese development projects in Africa, Latin America, and other nations of the “developing world” are aimed at resisting the global hegemony of American empire, when they are actually self-interested attempts by China to expand its geopolitical power. One notes that in seeking to expand its power outside its borders, China is seeking to attain the position of global hegemony currently occupied by the United States, and as a result, many of China’s actions are in fact modeled after American actions.

Apart from justifying the domestic imprisonment of Uyghurs, China has used the American discourse of a global “War on Terror” in order to justify deployments of the Chinese military in the Middle East, Africa, and other locations. With China acquiring ports in Africa, India, and other places, constructing its first overseas military base in Djibouti, the Chinese government may be taking the early steps to build a network of military installations across the world, similar to America’s global network of more than 800 overseas military installations.

Chinese-led initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and Belt and Road Initiative are aimed at expanding Chinese political influence through economic means. They are directly modeled after institutions such as the American-led International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The AIIB in particular could allow China to directly restructure national economies through conditional loans, much as how America imposed neoliberal economic reforms on Latin American countries using the IMF.

Photo credit: Haha169/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Haha169/WikiCommons/CC

China has been accused of carrying out a form of neo-imperialism or neo-colonialism, in saddling countries with expensive infrastructure building projects in the name of aid to create large national debts to China, or exporting its model of special economic zones in order to achieve economic dominance in various countries.

However, for Qiao, this will be read as part of efforts by China to resist western dominance. Qiao instead takes the view that China is seeking to align with other socialist nation-states, such as Iran, Venezuela, and others in order to combat western imperialism, rather than such alliances existing only for geopolitical reasons. Qiao also seems blind to cases in which the PRC acts much as the US does, exploiting smaller, less powerful countries for resource extraction.

China is simply “outside” of the logic of imperial powers for Qiao. Even when China carries out similar actions to western imperial powers, this is rationalized as a measure to oppose western imperialism—rather than being a case of convergent political behavior between two imperial powers.

Ultimately a Form of Diasporic Chinese Nationalism

WHILE QIAO considers contemporary China in utopic terms, with the view that China is wholly external to global capitalism and so qualitatively different than western countries—all signs to the contrary are ignored.

This view of a fundamental difference between China and the West is probably derived from a sense of diasporic Chinese Han nationalism, one which Qiao dresses up in the garb of leftism. One republished essay on Qiao’s website, “I Want to be Chinese,” proves telling. The essay states:

“Knowing I am Chinese is knowing that the civilization my grandparents, parents, and I descend from produced salt before Europe knew its taste. That it was this civilization that gave birth to thinkers and leaders like Sun Yat-sen, Mao Zedong, and Soong Ching-ling, who saw what the future needed in the face of a West doomed to fall apart and take the rest of the world down with it. These leaders knew more about human progress, requiring a new sense of morality, than the West. […] This civilization existed before the West, and it is something that can inspire our creation of a new world as the modern world as we know it collapses.”

As with all nationalisms, Qiao believes China to be qualitatively different and superior to other nation-states. Nationalist exceptionalism is why the same logic apparently does not apply between western nations and with China regarding domestic policing practices, the nature of the economy, or foreign policy.

Photo credit: White House/Public Domain

Photo credit: White House/Public Domain

For members of Qiao, as members of the diaspora, China represents something like an idealized homeland on which they can project their fantasies. This idealized homeland is juxtaposed with the western political context in which they live in and struggle with on a daily basis, as what might be thought of as a form of internalized self-Orientalism.

Ironically, Qiao’s vision of the world proves a highly dichotomous and Manichaean one, in which the only state powers that matter are those of America and China. Anything less than uncritical support of China is accused of being apologia for American imperialism—and one expects such criticisms to follow regarding this essay, New Bloom, and aligned projects that seek to be critical of both the US and the PRC such as Lausan. Yet this simply rehashes the politics of the Cold War, during which the Soviet Union was seen by many as representing the cause of socialism globally, and the world was framed as a binary between two competing superpowers, the USSR and the US.

Notably, Qiao ignores that the PRC and the Non-Alignment Movement, which included many of the countries that Qiao fetishizes, challenged this binary, with China making moves to supplant the Soviet Union’s position of leadership among nominally socialist or communist countries. Instead, in a post-Soviet political paradigm after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, Qiao slots China into the place that the Soviet Union historically occupied as the sole alternative to western imperialism. Alternatives to a world that is not simply divided between two competing superpowers are scarcely considered by Qiao.

This may return to Qiao’s diasporic position, in which the US is the political reality they live in and contend with on a daily basis, but China represents a longed-for political ideal. In many respects, Qiao’s dichotomous vision of the world proves a form of diasporic insularity.

In times of rising xenophobia against the Chinese diaspora, it proves easier to oppose one form of nationalistic atavism with another. Hence Qiao members have embraced a form of left-wing diasporic Chinese nationalism as a response to times in which right-wing white American nationalism proves increasingly dangerous.

However, insofar as Qiao’s diasporic Chinese nationalism is, in fact, defined primarily by its opposition to contemporary American nationalism, one notes that in many cases it sounds rather like transposing American liberal imperialism to a Chinese context. So, then, does Qiao’s thought prove highly statist in nature, inclusive of justifying contemporary Chinese imperial projects, or the actions of the Chinese state domestically.

Qiao has not thought its way outside of the framework of geopolitical contestation between nation-states, or the internationalism of people’s movements rather than nation-states, and it has deeply internalized the logic of the nation-state. As Nietzsche wrote, “A state, is called the coldest of all cold monsters. Coldly lieth it also; and this lie creepeth from its mouth: ‘I, the state, am the people.’” Qiao’s diasporic identification with the Chinese people sees the Chinese people as homologous with and equivalent to the Chinese state.

Photo credit: Dong Fang/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Dong Fang/WikiCommons/CC

It is probable that there will continue to be a wave of newly emergent projects similar to Qiao’s going forward. It proves harder to sustain a position critical of all nationalisms, or of the imperial actions of both China and America alike, and it proves easier to respond to nationalism with nationalism.

It would not be improbable that as America continues to drift rightward, this new generation of tankies among the newly politicized will continue to expand. This is why it proves crucial at this juncture to maintain a critical position of both the US and the PRC, and to point to the possibility of positions that are not simply campist ones embracing one form of nationalism or empire in opposition to another.