by Wei (Azim) Hung

語言:

English

Photo Credit: vTaiwan.tw/Facebook

BEING PART of a society, providing oversight, and evaluating the reliability and validity of campaign promises remains the responsibility of citizens. Our democracy is incomplete when the only memorable chant from a campaign rally is “frozen garlic” and when political slogans become a symbol of repetition that do not live up to their physical implementation. This is why citizens should take advantage of tools at their disposal to amplify themselves as meaningful stakeholders in society.

If you find yourself with a computer with decent Internet, vTaiwan is a tool accessible to everyone. vTaiwan is an online-offline consultation platform that allows ministers, experts, academics, and the public to come together to deliberate on certain issues. The philosophy behind the platform is to bring together relevant parties and members of the public with differing opinions.

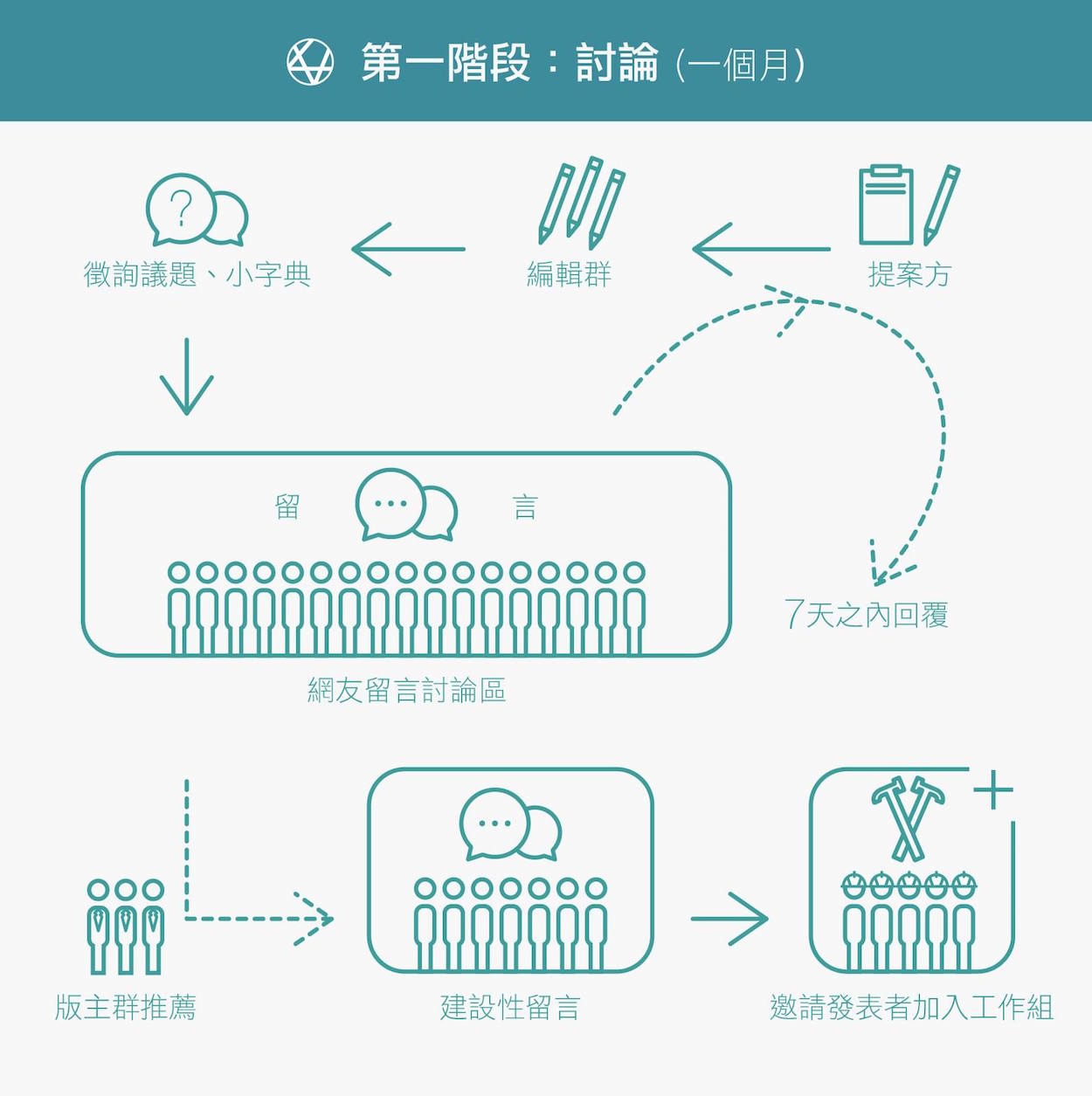

Diagram of the first stage of the vTaiwan process. Photo credit: vTaiwan.tw/Facebook

Diagram of the first stage of the vTaiwan process. Photo credit: vTaiwan.tw/Facebook

By doing so, the platform offers a new avenue for participants to have constructive conversations, with the hopes that this can allow for building consensus digitally on a variety of issues. For example, in 2015, with the controversy surrounding Uber regulation, vTaiwan was able to effectively address the challenge through its unique four-stage mechanism (Objective/Reflective/Interpretive/Decision Stage), and reach a consensus with taxi drivers in Taiwan.

In the objective stage, participants start by identifying common objectives, challenges, and other stakeholders involved. During this process, information and facts necessary to interpret the issue are gathered. Furthermore, to eliminate any potential barriers, technical difficulties such as understanding legal jargon will be raised in this stage, and professional terminologies are then translated into a vernacular language comprehensible to all stakeholders.

Second, in the reflective stage, a platform known as Poli.is is used. This primarily serves as a medium to collect the ideas and opinions of the participants in the post-objective stage. Through user-generated responses such as to pass, disagree, agree, or post a 140 character tweet in response to other users’ suggestions, Poli.is uses visual constructions to demonstrate existing patterns, allowing users to contrast and locate their positions with others in a given issue.

To move to the interpretive stage, the majority group and at least half of the minority group —would have to accept the established consensus. If a majority group of 60% of participants agrees, half of the minority group of 40% will also have to agree with the consensus, meaning that 80% of the total participants will have to agree. This forces participants to refine and reformulate any stances that are overly aggressive.

Third, in the interpretive stage, academics, experts, representatives from relevant ministries, and active participants on Poli.is are invited for a public meeting. The meeting is built upon figures, statistics, and knowledge collected in the reflective stage to formulate concrete proposals for discussion. Meetings are also live-streamed and transcribed, so participants online may also pitch in their opinion or ask questions digitally, which allows citizens to scrutinize and engage with actors on the other side.

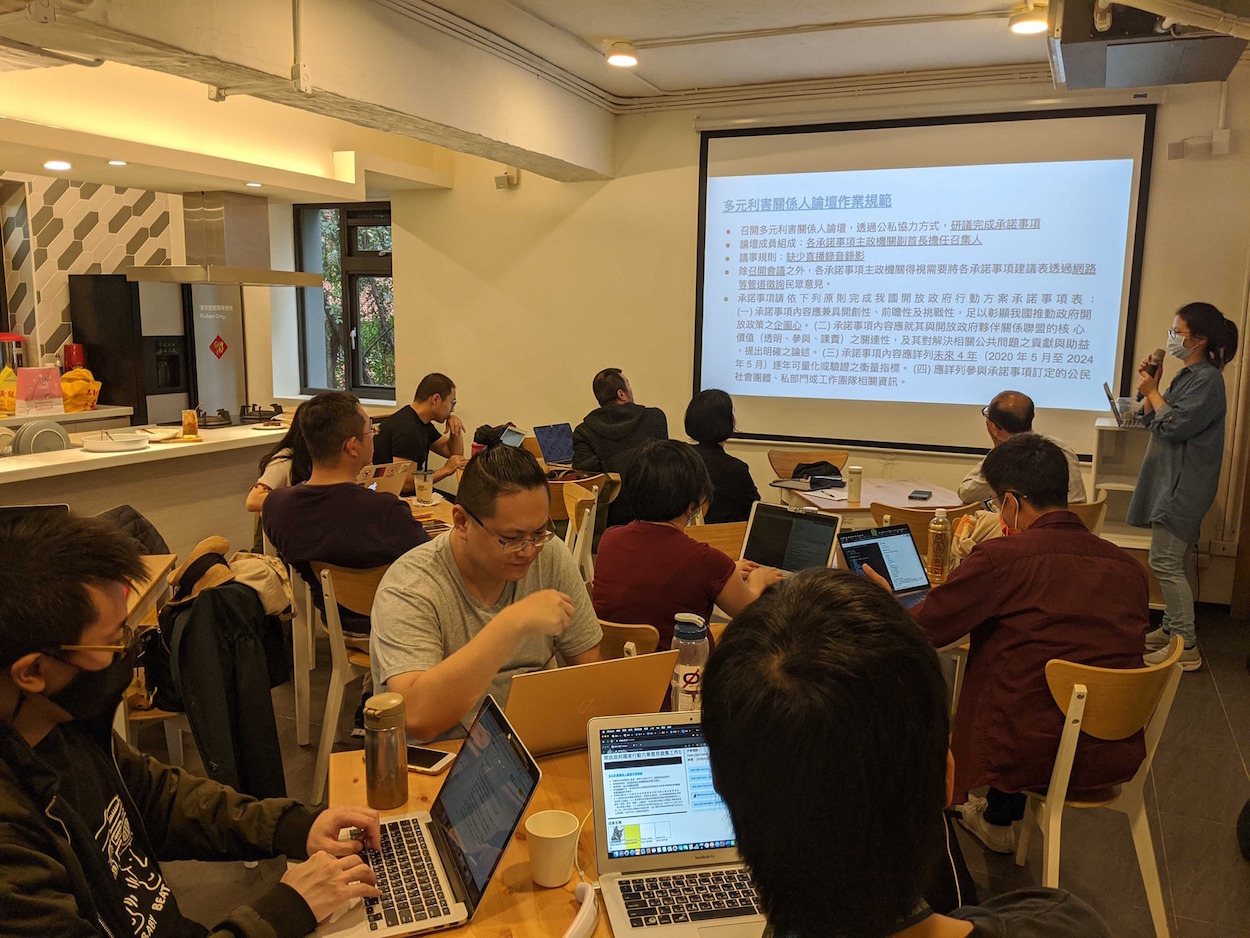

Photo credit: vTaiwan.tw/Facebook

Photo credit: vTaiwan.tw/Facebook

Lastly, in the decision stage, proposals from the interpretive stage are drafted into a bill and made ready for the government to ratify. With the issue of Uber regulation, the Tsai administration adopted most recommendations such as taxis not having to be yellow, having the standard taxi fare apply to all passengers, that taxis which operate using apps can only pick up passengers designated through the application, and etc.

Apart from Uber regulation, other issues that have been discussed on vTaiwan include the FinTech sandbox act, which allows the financial industry to conduct small-scale experiments that are regulated by the government; and the subject of Non-Consensual Intimate Images (NCII), with measures taken so that victims could participate in the discussion without the need to reveal their identities. These are past examples that have proven to be successful through the platform.

So why not continue giving voice to issues pertinent to our society? For instance, regarding the rollout of the new electronic ID (eID) that the Ministry of Interior (MOI) is attempting to implement by October, at the moment, dialogue between the government and the general public has primarily flown under the radar of the public. Criticisms have been raised by civil society groups, such as the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, Judicial Reform Foundation, and the Human Subject Protection Association, among others. But apart from objections by academics and Taiwanese civil society groups, formal dialogue between the general public and government has yet to be established.

Civic participation regarding the eID issue is particularly important. Unlike Uber regulation, FinTech sandboxes, or NCII, this is an issue that encompasses most, if not all of the citizenry as a whole. And in the case of the eID, citizens’ lack of participation has a wide array of ramifications for their civil liberties.

By allowing the government to centralize your data in one single database, you run the risk of a privacy breach, which could potentially expose your information to unsolicited parties with malicious intent, impeding your right to security. Moreover, the government has yet to provide a detailed account of the type of information that will be included in the eID, shrouding the entire matter with ambiguity. Active input from the citizenry is highly important regarding this issue, since this affects the privacy of citizens and participation will help safeguard one’s interests in the long-run when laws are being drafted, since a collective opinion from the vTaiwan process would be taken into account.

Photo credit: Ministry of the Interior

Photo credit: Ministry of the Interior

vTaiwan’s involvement could prove crucial in bridging this gap between the public, civil society, and the government regarding the eID controversy. Concerns over the lack of consultation from experts, government’s incompetence in the field of cybersecurity, and the MOI’s refusal to amend the law for the implementation of the eID are all valid concerns.

But this could be properly addressed through vTaiwan’s stakeholder engagement process. With regard to the issue of Uber regulation, taxi companies, drivers, and users of both taxi cabs and Uber engaged in the deliberation processes through the use of Pol.is and in-person deliberative discussions. In the end, concessions were made by all parties, resulting in a win-win situation where taxi drivers promised to elevate better service and Uber promised to work within the framework established through the deliberation process. And, again, it should also be noted that the Taiwanese government did ratify most recommendations on the issue of Uber regulation.

Anyone willing to contribute and scrutinize proposals is capable of doing so by hopping on Pol.is. The strength of democratic systems lies within its ability to call for self-correction. The government should adopt and encourage a similar approach to discuss issues such as the eID with the public. Participation and engagement to shape clear policy objectives and provide legal reports with one’s interest as a citizen in mind can allow for clarity on these contested issues.