by Peter Li

語言:

English

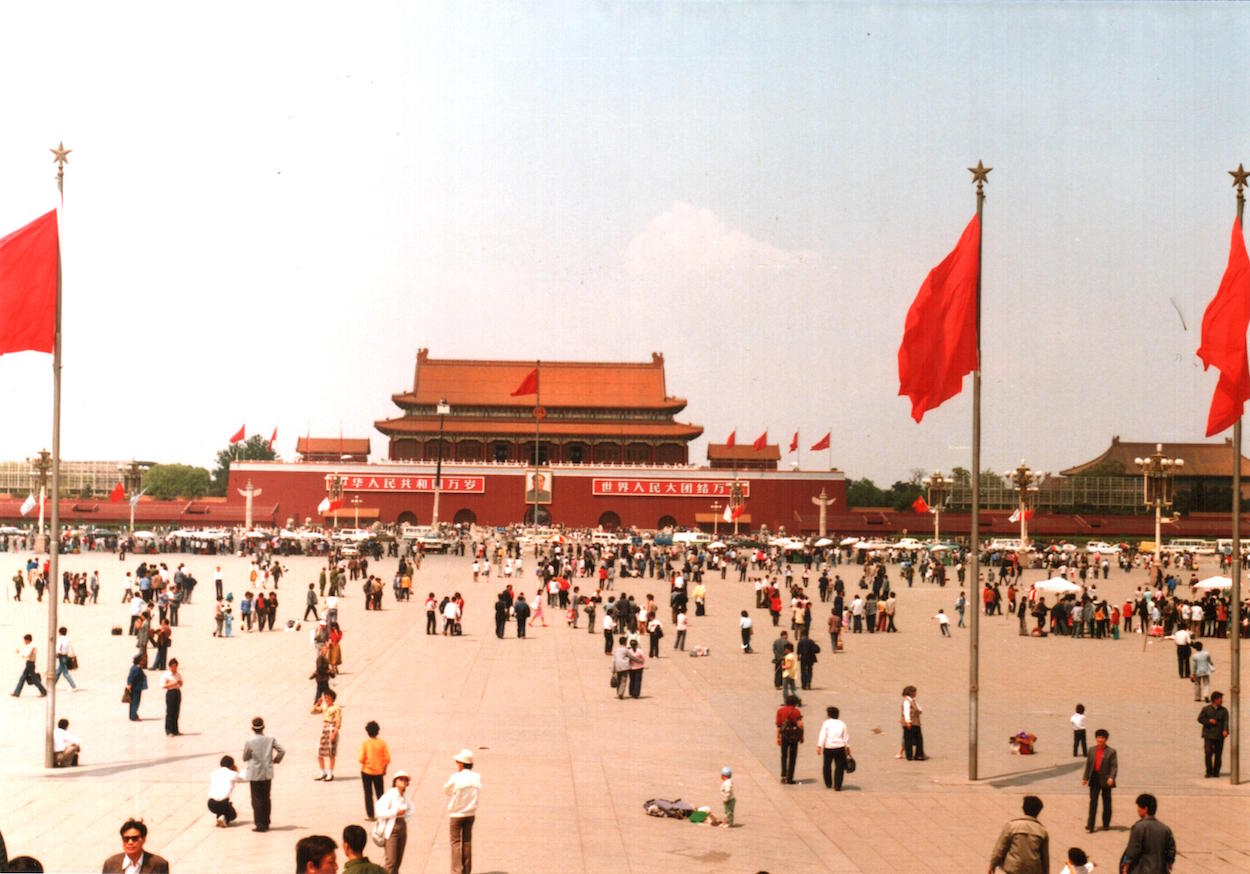

Photo Credit: Arian Zwegers/Flickr/CC

WHEN I STILL lived in Beijing, I once lived in Muxidi, a place where memories of the day will never fade. It was said that bullet holes can still be seen on buildings around the block.

I never saw them. What I remembered was the closure of the subway station exits every year. I was never bothered. It seemed to be quiet always. I would get home through another exit.

My first encounter with the memory of 1989 was at a very young age. “She was brave enough to go out!” commented my mother, talking about her sister.

Muxidi station in Beijing. Photo credit: N509FZ/WikiCommons/CC

Muxidi station in Beijing. Photo credit: N509FZ/WikiCommons/CC

I know what you are thinking. That she had gone out to participate in the demonstrations. Sorry, but you are wrong. She came out not to join the protest but, presumably, to buy new clothes. Both of them were among the millions of citizens who lived in Beijing at the time. They were not heroes.

I never seriously asked their opinions on this issue, either. I only knew what happened that day years after the conversation took place. My grandpa was a mid-level diplomat in the Ministry of Foreign Trade. He joined the Communist Party before 1949.

When he was no longer able to talk, I saw a pamphlet in his bookshelf, which was published by the Party after the movement was suppressed. Needless to say, it didn’t say anything good to those who were in the Square, but it contained part of the minutes for the meeting between the students and Li Peng, and also presented extracts of past newspapers during the movement, which showed the position of the protesters with excessive honesty. Distribution of this pamphlet was restricted, but it was not very difficult to get, since most Beijingers probably know one or two officials of mid-level or above.

I read the pamphlet at the end of my primary school years. In high school, I had a few very good teachers, with whom I had a chance to discuss the event in person. You may wonder if they followed the “orthodox” party line on this. No. On the contrary, they talked frankly and expressed grievance and discontent. But nothing else. What can we expect, after all?

I must apologize for making you swallow so many fragments of my memory. People may think that the demonstrators were all punished. They were not. The university graduates got jobs like their predecessors did, many were high-flyers and even became senior officials. The workers continued to work, or lost their jobs (and any guarantee of stable lives), sinking and floating in the recently-instituted “market economy”. And I, born five years later, was lucky enough to avoid the last remnants of the rationing system (which was abolished only a month before I was born), and live a relatively comfortable life. Thanks to the “Opening Up” policy, I even had the chance to study abroad.

Photo credit:

Photo credit:

June 4th was never forgotten in China, but it was never reflected upon. Vaclav Havel told people to reject the propaganda that no one actually believes, to live in the truth, and that the truth will ultimately set them free. The Europeans followed his advice and ended the Cold War.

I have always speculated that the Chinese in the 1980s were also living in the truth. At least they were true to themselves. They were true socialists, or true reformers, true democrats, some may even have been true capitalists. Their wish was to have China reformed.

Their wishes were accomplished, just in an upside-down way. In the cartoon Doraemon, there was a tool that grants your wishes, yet the way it does this is always more negative than positive. This was exactly the case for the Chinese “reform”.

A commentator in Hong Kong referred to June 4th as “the very last piece of memory of the Cold-War”. Paradoxically enough, it also effectively ended the Cold War in East Asia. In Eastern Europe, we saw democratization. Yet, like Proteus, it appeared in another form here in China.

The party seceded from its own realm of belief, betrayed its own ideological promises about Communism. And us, the survivors and descendants of survivors, betrayed our own moral senses to make a living, willingly or not. The West imposed sanctions on China for a while. Later, they started to believe that, since the Cold War was over and that history was going to end, China would finally change itself through economic integration and political interaction with the rest of the world. They were wrong.

Photo credit: Paul Louis/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Paul Louis/WikiCommons/CC

“Emptying their hearts, and filling their bellies. Weakening their intelligence and toughening their sinews.” This was the ancient wisdom (or anti-wisdom) of Lao-tzu. Obviously, this was practiced after 1989, thanks to economic collaboration with the West. Consciously or not, they were partially responsible for the situation. Aristotle observed that the tyrants desire to have mean-spirited subjects, who also distrust their peers and are incapable of action. This may be exactly the case in present-day China. We see the “little pinks” (小粉紅) who are excited to attack foreign “enemies” online but may never be able to trust any of their fellows, crying in vain for help after their own rights are infringed upon by the government. For these “pinks”, this may be (but not quite, actually) a kind of return of the repressed. For the Western world, facing such a monster is nevertheless a form of payback for having misunderstood the situation.

Commemoration is never meant merely to remember those victims. It is also about us, all of us, about our relationship with them. We failed them. The Chinese failed them by surrendering meaning in exchange for simply living. The West failed them, too, and the consequences were never fully examined and understood. Thus, the injustice that victims suffered were not relived, but deepened, and became a torment for all of us. June 4th never ended. The massacre is still going on.