by Wei (Azim) Hung

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Heeheemalu/WikiCommons/CC

UNDER THE grand diplomatic strategy of successive administrations in Taiwan, Lee Teng-hui, Chen Shui-bian, Ma Ying-jeou, and Tsai-Ing wen have all attempted to craft a Southbound (Go South) Policy with attributes pertinent to the time-space of its given historical context. Fundamentally, to discuss the New Southbound Policy or its predecessors without analyzing the government’s diplomatic strategy vis-à-vis cross-strait policy is a disservice to any insightful discussion, due to the two determinants having a direct impact on the strategic objectives of the Go South Policy. This piece, through an analytical lens, would provide context on the continuities and changes of the NSP from previous GSP. It would then explore the political and economic logic behind NSP, and lastly, conclude with the current limitations faced by the government and how these limitations can be overcome.

Pragmatic, Offensive, and Viable Diplomacy

THE FIRST phase of Lee’s GSP primarily addressed the issue of Taiwan’s shrinking international space after experiencing the full-brunt of being expelled from the United Nations in 1971 and the termination of diplomatic ties with major countries such as Japan (1972) United States (1979), Saudi Arabia (1990), South Korea (1992) and South Africa (1998). To provide the status quo with remedy, Lee pursued a series of pragmatic diplomacy in conjunction with an attempt to curb cross-strait economic ties by putting a cap on investment limit – albeit with little success. His primary objectives were to re-expand Taiwan’s international space, diverting investment from China, and increase relationships with other Southeast Asian governments on a national and sub-national level through foreign aids, investment, and scheduling high-profile holidays in these countries. However, as Lee initiated the second phase of his GSP intending to increase Taiwan’s economic leverage and presence from the success of phase one, he was met with the Asian Financial Crisis and increasing anti-Chinese sentiment across the region, bringing a halt to the project. [1]

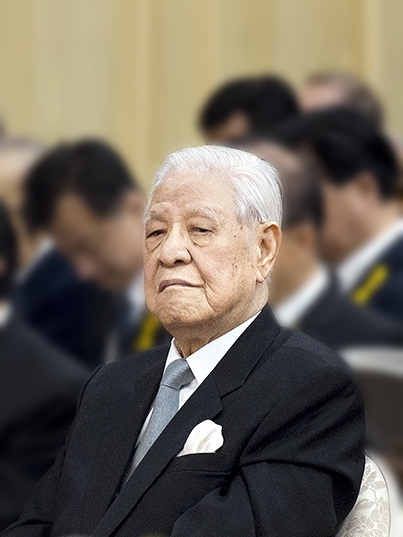

Lee Teng-hui. Photo credit: Presidential Office/Public Domain

Lee Teng-hui. Photo credit: Presidential Office/Public Domain

Chen took inspiration from Lee’s Southbound strategy but took it one step further, believing that Lee could have enacted policies seen as more aggressive such as signing Free Trade Agreements and directly lobbying foreign parliamentarians, which for Chen, would increase Taiwan’s regional visibility and provide the symbolic recognition of sovereignty it seeks from neighboring countries. Nevertheless, one major obstacle Chen faced was the fact that, since the People’s Republic of China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, many Southeast Asian nations started to align with China due to a better investment climate and under the principle of One China Policy. Chen ultimately had to reorient policy focus on domestic politics as his GSP has lost its appeal and impetus. However, that is not to say Chen’s initiative ended in abysmal failure. Quite the contrary, although he failed to divert Taiwanese investment in China to Southeast Asia, he was still successful in strengthening economic relations with regional neighbors and marginally reducing dependence on China.

On the other hand, Ma, unlike his predecessors, never explicitly proclaimed nor adhered to a specific Go South guideline. Furthermore, his viable diplomacy shared similar characteristics to Lee’s pragmatic diplomacy, except on top of pragmatism, he also prioritized maintaining a cordial relationship with China, forgoing any possible political or symbolic benefits of sovereign states, a sharp contrast to Lee and Chen. Comparatively, Ma’s policies were relatively successful in securing more than a dozen economic and technical agreements with China, especially the Economic Cooperative Framework Agreement (ECFA), a preferential trade agreement signed in 2010. He also doubled the amount of ASEAN students studying in Taiwan, bringing the number to 26,756; and signed an agreement of Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu on Economic Partnership (ASTEP) with Singapore. [2] However, the ASTEP remains the only regional breakthrough on FTA; even under a cooperative Republic of China administration. That said, Ma was able to enjoy tangible benefits and make concrete improvements as he focused more on fostering cultural and economic ties while reducing political skirmishes with the PRC.

The New Southbound Policy

TSAI’S NSP could be examined based on its short to mid-term and long-term goals. The former includes a ‘two-way’ exchange in tourism, investment, culture, talent, and trade-relations. But also to enhance multilateral and bilateral negotiations to increase dialogue through cooperation. The latter is more ambitious in the sense that the government strives to forge the notion of an economic community stretching from India down to New Zealand, which can benefit through a positive-sum mechanism. Most importantly, in the long-run, it would develop into a community with trust transcending national borders. [3]

Based on the analysis above, some continuities carried onto Tsai’s NSP in 2016 include continuing the strengthening of bilateral economic ties and elevating Taiwan’s overall presence in Southeast Asia, which has been consistent throughout the years since Lee. What is exclusive to Tsai’s NSP is the emphasis of people-to-people exchange on education, industrial talent, new immigrants, and the government’s goal to de-emphasize unilateral investment in the region while expanding reciprocal investments and tourism. For example, to accentuate its agenda on tourism, the Tsai administration had extended visa-free entries for neighboring countries such as Brunei, Philippines, and Thailand. Furthermore, although Ma also encouraged people-to-people exchange, the Tsai administration made it their priority, substantially devising concrete policies encouraging young talents to intern or study in the eighteen targeted countries through the Ministry of Education’s NSP Educational Exchanges.

The Logic Behind Deepening Regional Roots

THE INTUITIVE response in finding the necessity of a Southbound Policy is first and foremost, based on cross-strait security concerns. To counterbalance China from having too much economic and political leverage over Taiwan’s growing economic dependency. Since Taiwan lifted the travel ban in 1987 and direct flights established in 2008, the sum of bilateral trade has only increased throughout the years. For example, in 2010, 40% of domestic goods produced in Taiwan were exported to China and Hong Kong, and in 2018, the export/import aggregate reached a total of $150.5 billion. In this regard, it is only rational for the government to draw counter-measures to diversify the economy, instead of channeling all resources into one single market.

Photo credit: Foxy Who \(^∀^)//WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Foxy Who \(^∀^)//WikiCommons/CC

In addition to security concerns, reducing xenophobic sentiments toward South and Southeast Asians and prudence in economic investments are also reasons to undertake a Southbound Policy. It would be farcical to make sweeping generalizations on Taiwanese people being racist. However, prejudice and horrible treatment of migrant workers have long been a standing issue in Taiwanese society. By encouraging cultural exchanges, this would better help Taiwanese society in accommodating new immigrants, and improving the treatment of migrant workers. Furthermore, it is also necessary for Taiwanese investments to be relocated to SSEA for practical economic reasons. As the Chinese government continues to restructure its capital-labor relationship, it is currently working towards smart manufacturing. That is to say, reforming the environment into one that is suitable for innovation-driven manufacturing replacing labor-intensive ones. A case study would be the transformation of Shenzhen from an industrial enclave into a smart city. [4]

Economic Independence under Chinese Pressure

WITH THE reasons aforementioned, it is justified for the government to engage in an NSP. However, one major criticism of Tsai’s NSP is an assertion echoed by KMT politicians, claiming that poor cross-strait relations will hinder the development of the NSP, effectively mitigating the benefits the government wishes to reap.

While it is true since Tsai’s rejection of the 1992 consensus during her inauguration address significantly cooled cross-strait relations, it is faulty to assume that pressure from Beijing would vanish through improved cross-strait ties. Firstly, as Ma’s tenure has illustrated, even under a cooperative, pro-China administration, the only breakthrough the government was able to secure was an FTA with Singapore. Secondly, even under an optimal cross-strait scenario, which would provide Taiwan with an amicable climate with its neighbors, it will be against China’s interest to isolate Taiwan as a sovereign entity. It is appropriate to see Taiwan’s relationship with China as a zero-sum one, as Chinese acquiescence will inevitably jeopardize their leadership and vice versa; therefore it is unsurprising to observe the constant interference on the international stage to subjugate Taiwan. [5] In this capacity, the Tsai administration should vociferously push for their NSP regardless of cross-strait relations.

The Limitations of the New Southbound Policy

WHILE THE initiative itself deserves praise, structural problems of the NSP should not be overlooked, as there are clear limitations that need to be recognized and amended. There exists a multitude of problems to be addressed, but for the sake of brevity, this section will focus on two issues, namely insufficient budget and weak inter-agency coordination.

Most of NSP’s current budget is from the existing annual budget for NSP countries or budgets supposedly allocated for other countries in the region. In 2018, the government increased the NSP budget by 63%, amounting to 2.8 billion NTD. But as Kwei-Bo-Hwang points out, the magnitude of the projects that the Tsai administration attempts to take on significantly dwarfs the size of her budget proposal. [6]

Tsai Ing-wen. Photo credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

Tsai Ing-wen. Photo credit: Tsai Ing-wen/Facebook

Moreover, for a foreign policy of such scale, sound inter-agency coordination is indispensable. Tsai is currently serving her second term, to sell her NSP both domestically and regionally, she needs to amend and improve the mistakes seen during the first-half of her tenure. The complex bureaucratic nature of the NSP is demonstrated by the wide array of agencies the Office of Trade Negotiations have to interact with, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Education, Tourism, Finance, and so on. An example of weak inter-agency coordination under Tsai’s watch was that the New Immigrants Affair Coordinating Committee had not convened itself six months after her administration announced the NSP. The Control Yuan has also advised the government on behalf of room for improvement when it comes to coordination and resource allocation. For Tsai’s NSP to be a success, a sufficient budget and enhancement in inter-agency coordination are two primary problems necessary to be combatted. [7]

Conclusion

THE NSP being one of Tsai’s flagship policies has its purpose grounded in cultural, economical, and security concerns. With hindsight from Lee, Chen, and Ma at hand, Tsai has the privilege to steer clear of past blunders. It is also worth stressing that due to the effects of protests in Hong Kong, Tsai’s landslide victory in January, and the outbreak of COVID-19, cross-strait relations are at an all-time low. With that in mind, Tsai should tread carefully on her policy and not overly politicize her agenda, as Chen did. For any substantive developments to occur, Tsai needs to avoid giving other people the impression that the NSP is a byproduct of cross-strait tensions. If so, this would frame the overall initiative as insincere, effectively obstructing her vision of a regional economic community.

[1] Lindsay Black, “Evaluating Taiwan’s New Southbound Policy: Going South or Going Sour?” Asian Survey 59, no. 2 (2019): 249-51.

[2] Ngeow Chow Bing, “Taiwan’s Go South Policy: Déjà Vu All Over Again?” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 39, no. 1 (2017): 110-12.

[3] Kwei-Bo Huang, “TAIWAN´S NEW SOUTHBOUND POLICY: BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVES, FRAMEWORK AND LIMITS.” Revista UNISCI, no. 46 (2018): 53.

[4] Ling Li, “China’s Manufacturing Locus in 2025: With a Comparison of “Made-in-China 2025” and “Industry 4.0”.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 135 (2018): 68-73.

[5] Denny Roy, “Prospects for Taiwan Maintaining Its Autonomy under Chinese Pressure.” Asian Survey 57, no. 6 (2017): 1135-38.

[6] Huang, “TAIWAN’S”, 57.

[7] Ibid, 58-61.

Works Cited

Bing, Ngeow Chow. “Taiwan’s Go South Policy: Déjà Vu All Over Again?” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 39, no. 1 (2017): 96-126.

Black, Lindsay. “Evaluating Taiwan’s New Southbound Policy: Going South or Going Sour?” Asian Survey 59, no. 2 (2019): 246-271.

Huang, Kwei-Bo. “TAIWAN´S NEW SOUTHBOUND POLICY: BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVES, FRAMEWORK AND LIMITS.” Revista UNISCI, no. 46 (2018): 47-68.

Li, Ling. “China’s Manufacturing Locus in 2025: With a Comparison of “Made-in-China 2025” and “Industry 4.0”.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 135 (2018): 66-74.

Roy, Denny. “Prospects for Taiwan Maintaining Its Autonomy under Chinese Pressure.” Asian Survey 57, no. 6 (2017): 1135-1158.