by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

Photo Credit: Historical Photo

WITH THE 40TH anniversary of the 1979 Kaohsiung Incident today, also known as the Formosa Incident or Meilidao Incident, it may be worth reflecting on what has changed in Taiwan in the decades since then—but also to what extent many of the tasks of Taiwan’s democracy movement remain unfinished.

The Kaohsiung Incident took place on December 10th, 1979. The incident was a pivotal moment in Taiwan’s democratization, with the arrest of eight dangwai movement activists by the KMT during a demonstration commemorating International Human Rights Day becoming a highly publicized incident. The members of the “Kaohsiung Eight” included many individuals that later became prominent DPP politicians, including Chen Chu, Annette Lu, Huang Hsin-chieh, Shih Ming-teh, and others. The defense lawyers of “Kaohsiung Eight” themselves became prominent DPP politicians as well, including individuals such as Chen Shui-bian, Su Tseng-chang, Frank Hsieh.

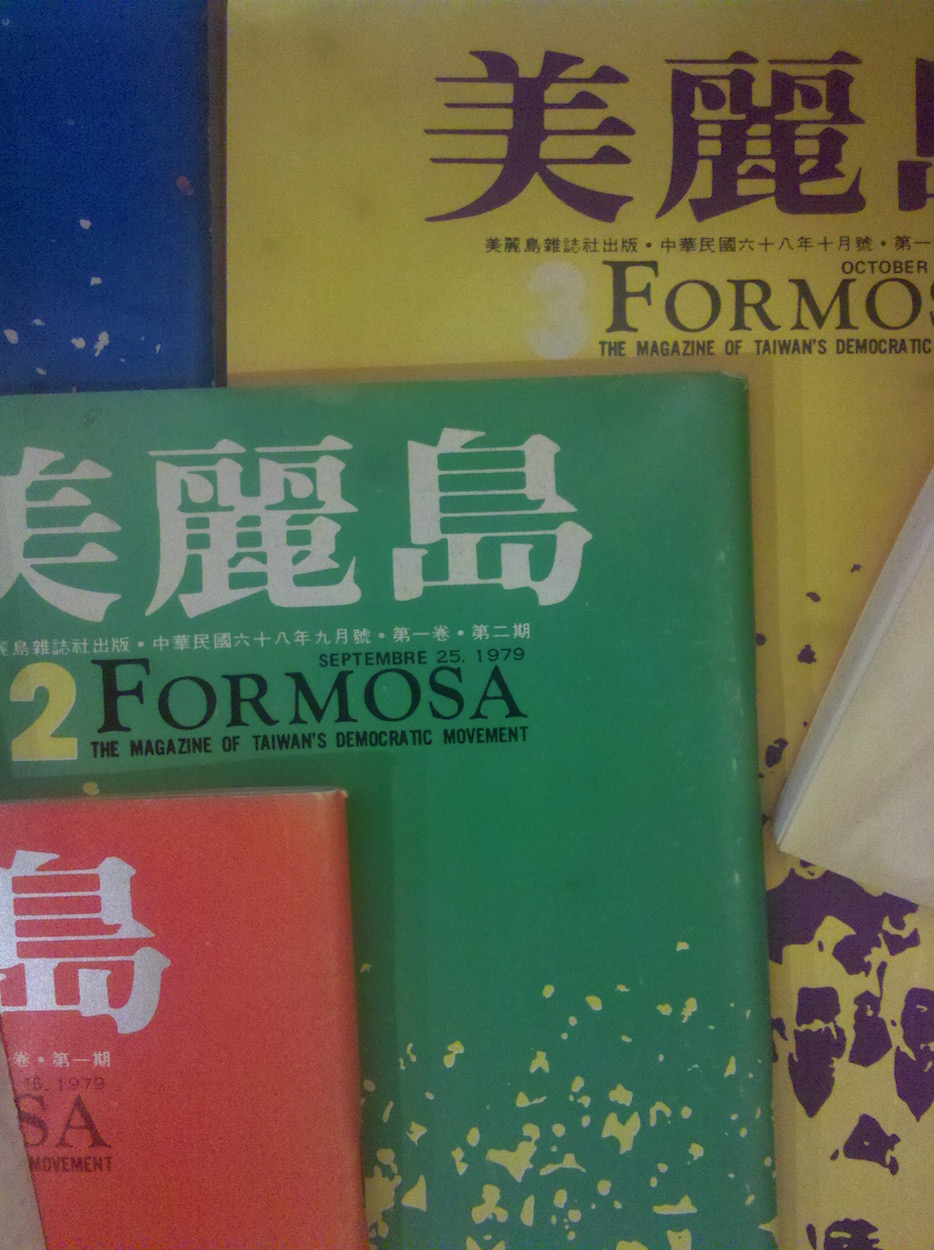

Participants in the demonstration were affiliated with Formosa Magazine. Photo credit: Christopher Adams/WikiCommons/CC

Participants in the demonstration were affiliated with Formosa Magazine. Photo credit: Christopher Adams/WikiCommons/CC

Though the “Kaohsiung Eight” and their defense lawyers are the best-known figures of the Kaohsiung Incident, further waves of arrests took place after the incident, including of other participants in the demonstration or of individuals that sheltered them. The Lin family massacre, the killing of Lin Yi-hsiung’s mother and twin daughters by unknown individuals, took place in the aftermath of the incident, taking place three months later in February 1980.

Four decades later, with Taiwan having gone through several peaceful transitions of power at this point, most would deem Taiwan to have become a democracy. In this sense, there are some who would view the Kaohsiung Incident as a long past event, belonging to an entirely different era of history.

However, the truth behind many events of this period is still opaque. The culprit of the Lin family massacre remains officially unknown, for example, despite that the Lin family residence was under 24-hour surveillance during that time, pointing to the obvious fact that the incident was one orchestrated by the Taiwan Garrison Command.

While efforts to push for transitional justice have taken place under the Tsai administration and previous DPP administration, it is likely that some individuals complicit in the crimes of the KMT during the authoritarian period remain free, may still be a part of the government, or may still be a part of political life in Taiwan. And it proves hard to take action against such individuals now, decades later.

Though Taiwan’s democratization was fought for by dangwai activists, a number of whom paid for their political activism with their lives or spent many years in jail, the KMT now even claims that it is the DPP which is engaged in political persecution through efforts to rectify the past crimes of the authoritarian.

Chen Chu. Photo credit: Public Domain

Chen Chu. Photo credit: Public Domain

Indeed, the KMT is the former authoritarian party and the DPP emerged from the Taiwanese democracy movement. But the KMT has adopted the discourse of claiming that the DPP is engaged in a “Green Terror” far worse than the KMT’s “White Terror”—though one wonders where the tens of thousands of dead bodies in the four years since the Tsai administration took power are, in that case. This is used as a means of targeting the DPP’s efforts to push for transitional justice or its targeting of the KMT’s illicit party assets retained from the authoritarian period, which some believe makes the KMT one of the world’s wealthiest political parties.

Reflective of the means by which the KMT originally came to Taiwan as a settler colonial regime, with its party members constituting an economically and politically privileged elite whose governing ideology was a form of Chinese nationalism, the KMT continues to advocate unification with an increasingly authoritarian China. For a party that once ruled over Taiwan through an authoritarian party-state, it hardly matters that this would mean the loss of Taiwan’s hard-won democratic freedoms; KMT members likely imagine that they could retain their elite privileges under Chinese rule.

It is true that the political trajectories of some of the individuals involved in the Kaohsiung Incident have left something to be desired. Annette Lu, for example, is well-known for her homophobia and racism, Chen Shui-bian later faced charges of corruption, and Shih Ming-teh later drifted toward pro-China viewpoints himself.

However, at the same time, the contemporary denigration of participants in the Kaohsiung Incident or individuals exiled from Taiwan during the blacklist period by Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je reflects the degree to which Taiwanese society has not actually come to grips with the incident. Ko himself is an individual who has become increasingly distant from the pan-Green camp since his original election victory in 2014 due to affiliating with individuals including killers of political dissidents such as “White Wolf” Chang An-lo and former government officials involved in the political repression of dangwai dissidents as James Soong.

Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je and members of his recently formed Taiwan People’s Party. Photo credit: 柯粉俱樂部/Facebook

Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je and members of his recently formed Taiwan People’s Party. Photo credit: 柯粉俱樂部/Facebook

To this extent, it is significant that both Chang and Soong remain active figures in Taiwanese politics. No less than former police official Hou You-yi, who was directly responsible for the events that led to the self-immolation of “Nylon” Deng Nan-jung, became mayor of New Taipei last year after November nine-in-one elections. Again, individuals that commit crimes during the authoritarian period are still very much presences in Taiwanese political life.

Perhaps, then, what should be reflected on 40 years after the Kaohsiung Incident is to what extent the tasks of the Taiwanese democratization actually remain unfinished. This proves something Taiwan may be in crucial need of reflecting on, with just over thirty days left before 2020 elections, and the KMT seeking to retake power.