by Brian Hioe

語言:

English

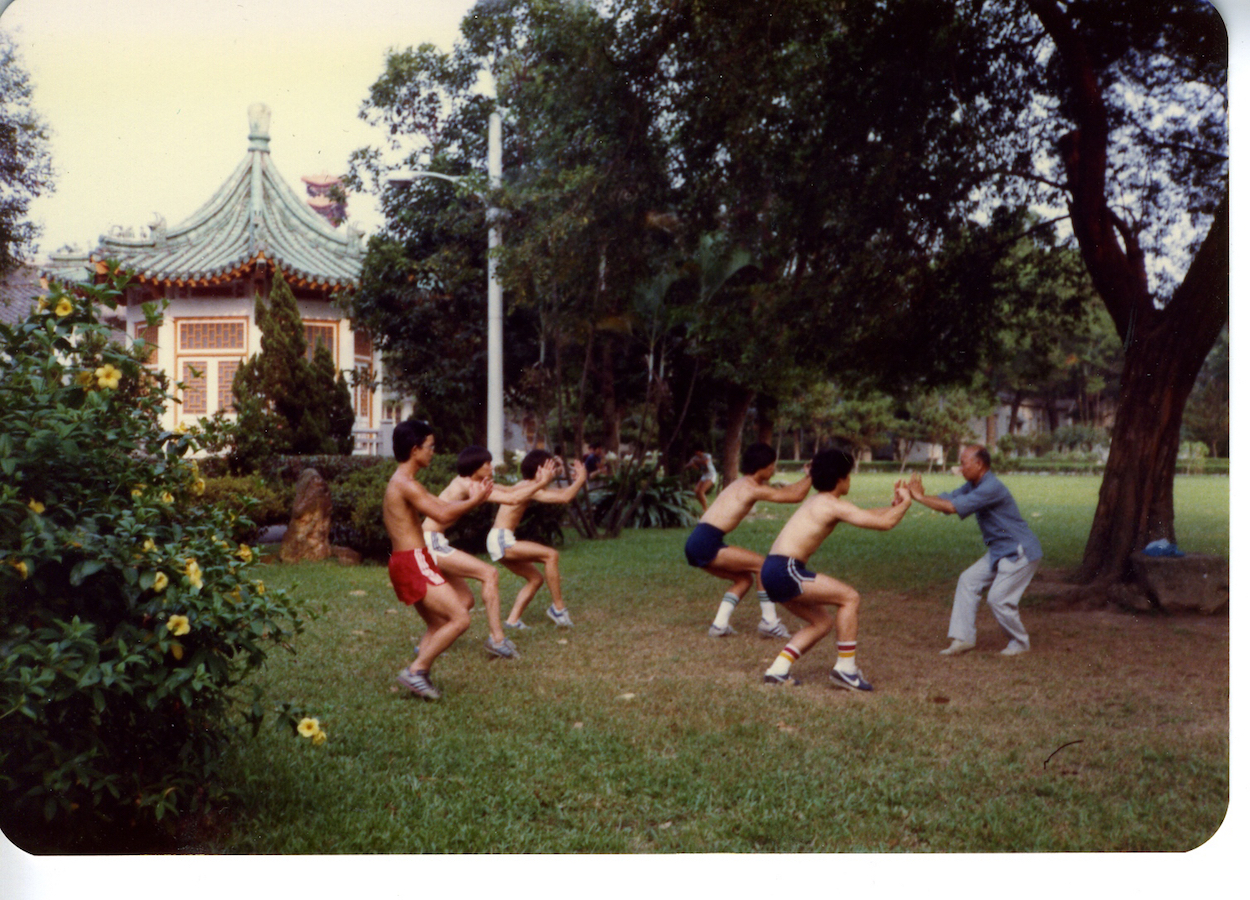

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

New Bloom editor Brian Hioe interviewed Valerie Soe, the director of Love Boat: Taiwan. Love Boat: Taiwan is a recently released documentary about the Overseas Compatriot Youth Formosa Study Tour, better known as the “Love Boat”, a program which provides a monthlong tour of Taiwan for individuals of Taiwanese or Chinese descent born outside of Taiwan or China from 1967 onward. The “Love Boat” program remains widely known among diasporic Taiwanese even today.

Soe and Hioe’s conversation, which was conducted by e-mail after a meeting in Taipei, is reproduced below.

Brian Hioe: First, for readers that don’t know you, could you first introduce yourself.

Valerie Soe: Sure. I’m Valerie Soe from San Francisco. I’m a professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University. And I’ve been making films since the 80s. Mostly short films. Actually, Love Boat is my first feature film.

BH: As comes up in the film, you participated in the Love Boat program. When was that and kind of how would you describe it?

VS: I went on Love Boat when I was in college. That was 1982. It was a long time ago. But I think I went I was 20, so probably about the age that most people will go. That’s about the median age, I would say.

And how did I hear about it? I don’t know. I really can’t remember. I’m sure my parents had something to do with it.

Director Valerie Soe. Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Director Valerie Soe. Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

BH: So that seems to have left a deep impression on you, otherwise you would not be making a film on the program so many years later. How would you describe that in your own terms?

VS: Well, there are a couple of different ways to think about this. First of all, as a filmmaker, I recognized that it was an interesting story. So just objectively even if I hadn’t gone on the trip, I think I would have been interested in making a film about it, because I think it does have a lot of cultural resonance to Taiwanese Americans and Chinese Americans. And I think in Taiwan, too, although I think in Taiwan the program is less acknowledged because the program is not really addressed to them–it’s addressed to outsiders to Taiwan.

But then as a person who went on the trip, of course, I went when it was a very formative time in my life, which when I think most people go. They know when it’s like they’re still really thinking and changing and trying to figure out what their opinions are about a lot of things. So I’m pretty sure it must’ve had some influence on my development at that point.

BH: It’s quite funny to me, because I’ve been hearing about the program for years, but I didn’t know too much about the details until I watched your film actually–outside observer. I also was under the impression that the program had been shut down. I think a lot of people are under that impression.

VS: You can say it doesn’t exist as it did in its heyday. The government may or may not say that it exists still. There are still programs that are sponsored by the government.

People call those programs Love Boat, but I don’t know if those are necessarily considered the classic Love Boat. I know people still use that term very loosely.

BH: Your film actually features Love Boat participants all the way back to the first trip. How did you find the interviewees from all these different generations? It goes all the way from the first generation until the one in 2013, when there was an incident.

VS: I want to say technically the first trip was 1966. It was the year before we started the film, but only a handful of people went on that trip. So the person that we interviewed from 1967 said, “We were really the first Love Boat,” which I think for the purposes of the movie I think it’s fine to say. But if you want to be strictly academic and accurate, you probably say 1966 would be the very first time the government tried to do a program like that.

How did I find these people? A lot of word of mouth.

The research period was pretty long. A couple of years at least. It really involved just sort of reaching out to people. I actually started working on this film in the late 90s originally. But I wasn’t really actively working on it for a long time. When I did start actually actively working it, it was in 2013 or 2014, and then it was just a lot of reaching out to people.

Luckily social media was around at that point. So I think I might have just talked to people and mentioned it to them and then they said, “Oh, I know somebody who went on it.” And then the research became a little bit more systematic.

Once I was introduced to someone like Pierre Wuu or Ben Shyu, who had a huge amount of contacts, that just exponentially increased the number of people who I could reach out to. I think I might have sent out an email to an email list that Pierre sent me when I was looking for people.

I also had a survey online at one point that people could fill out to talk about their experience. And then the last question was, “Would you be interested in being interviewed on camera?”

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

BH: Were there stories that surprised you from some of the participants? Including stories that made it into the movie and that didn’t?

VS: A lot of people’s stories were fairly similar so to find people who had different kinds of stories, that was more of a challenge because I think a lot of people had uniform experiences. I did try to find people who had less than fabulous experiences, who have more of a critical distance.

For instance, Kristina Wong is in the movie. She’s the person who reads from her diary. She was really great because she had a really good experience, but she also had a critical distance where she could analyze her experience and think about what the flaws were in the program.

She wasn’t as completely in love with the program as some people were. Some people have so many positive memories that they can’t really distance themselves from it. And that’s fine. If that’s the memory that they have, then that’s the memory they have.

It was good to find people who were able to evaluate it more critically as well. There were a few people who had negative experiences. Some people who had negative experiences didn’t want to be interviewed. That was also a problem. They just didn’t really enjoy themselves and they didn’t feel like they wanted to be on camera.

There’s a person who was in the film who said the program was typical heteronormative shit. She talked about how it wasn’t really useful for her in a lot of ways, not only because it was so heteronormative, but also because she is younger and so she very strongly identified with Taiwanese American identity, and she had been back to Taiwan a lot.

It wasn’t such a novelty for her to go to Taiwan, because she’d already been back every year visiting her relatives. She felt like the program in some ways was too superficial, because she knew Taiwan so well. And I think that that happened with a lot of the later people, the younger people, maybe after 2000. At that point, a lot more people started coming back to Taiwan.

By contrast, for me, when I went in the 1980s Taiwan was so far away and it was so expensive to travel back and forth. Taiwan was less developed, so it wasn’t as friendly to foreigners–foreigners being me. I really didn’t know how to speak Mandarin. There was no subway. So all of this stuff made it a lot more difficult to penetrate. But now it’s so much easier for us to come over and visit.

BH: It came up in the Q-and-A during the premiere screening in Taipei. You mentioned the generational differences between the people you interviewed. Could you talk about that a little bit?

VS: Yeah. For example, especially in 1967, it was really so hard to get to someone or to Asia or, for that matter, anywhere overseas because it was so expensive. And as the years went by, then there was more air travel and, of course, after the Internet started up, people became more familiar with things outside of their own personal sphere. So Asian Americans didn’t feel like they were so isolated from Asia.

It’s also significant that after 1967 in the US, the Immigration Reform Act changed the laws about how people could immigrate. So there were all of a sudden a lot more people immigrating from Asia. In the US, the generation that came after 1967 was huge. There was a tenfold increase in the amount of Asian Americans in the country, before and after 1967.

So because there are a lot more people who are immigrants, as opposed to my family who have been in the country for two or three generations, who are American-born, there is a lot more connection with Asia between those people living in the US. Because they just came from there. There is a lot more transnational awareness and global identity.

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Whereas back when I was growing up, we were really rooted in the US. China and Asia were kind of this vague memory. We would celebrate Chinese holidays and occasionally go eat Chinese food in Chinatown and do some of the traditional stuff. But we weren’t really connected in that way that immigrants who came from Asia are. But now that has switched. A lot more Asians from Asia are living in the US. than Asians who were born in the US. The Asian American population is more immigrants than American-born now.

Same thing with Taiwanese Americans. They started to come over in the 1970s and 1980s. So they were really connected to Taiwan still. For them, when their kids grew up in the 2000s and went to Taiwan, it wasn’t such a huge novelty to go over there, since they spoke some of the language, they may be still had family back there, etc. That was a big difference.

BH: I want to ask about you including your own experiences in the movie because I think it’s kind of very unique. You also brought this up during the Q-and-A during the screening. Could you talk a little bit about that decision, to include your own experiences in the movie?

VS: My earlier movies, like my short films, were very autobiographical. They were personal documentaries or from a first-person perspective and at some point along the way, I don’t even know when this was, I started to get away from that. Because I felt like, for me, it was a very easy solution to making movies, by narrating them yourself. You can fill in all the holes, you can try and make it about yourself. That’s a good strategy for getting people to watch your movie, because a lot of people like to hear personal stories.

But I felt like this story was so much bigger than my personal story. I didn’t want it to be about me going back to Taiwan and figuring out what happened to the Love Boat. Because that seemed really simple to me. At the same time, I did want to show that the program had a big impact on me. And so I thought it was kind of humorous to make me one of the many characters in the movie.

It’s kind of a meta thing. You suddenly realize this director of the film is also in the movie. Although people who know me obviously recognize me right away.

The payoff is when the audience member realizes, “Oh yeah, she was so influenced by the program that she actually made a movie about it.” That’s kind of funny to me.

I also did want to get away from just centering myself in the film because I don’t think it’s only just about me. My story is not the most interesting one in the movie by far, but it is one of the stories.

When I had work-in-progress screenings, a lot of people asked me if I was going to be in the movie. Even from the very beginning of the movie, when I started reaching out to people, people asked me, “Are you going to be in this movie?” It’s a funny little thing to get people interested in the story.

It’s also worth mentioning that my family is not Taiwanese. People sometimes ask me, “Oh, you’re Taiwanese? That’s why you made this movie?” And I’m like, “Sorry, I’m not Taiwanese.”

I don’t think it matters that much, but I think it’s also important if you know the more intricate details of Taiwan, to realize that back when I went in the 80s, the government of Taiwan (the ROC) considered themselves to be the government of China. That’s why Chinese Americans were welcome because they thought everybody was Chinese, whether Taiwanese or Chinese. They thought Taiwanese were Chinese, that people in China were Chinese, and that Chinese Americans were Chinese.

So that’s in what sense that I was why I, as a Chinese American, went on the program. Because of the ROC.

BH: You also mentioned during Q-and-A some differences in the kind of participants or in the program itself over the course of time. The program, after all, began during the authoritarian era and proceeded through democratization. You also see the identity shift over time regarding Taiwan and China.

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

VS: I was hoping that we could get into like some of those details, as far as the political complexities. It’s hard, though, because Taiwan is so complicated. The history is so complicated. At some point, some people watching the movie might think, “Why are some people calling themselves Chinese and some people calling themselves Taiwanese? Why are they saying that they’re Chinese, but they’re in Taiwan?”

We had to really make a lot of decisions about how much detail we needed to go into as far as those histories are concerned.

The hard thing to decide was which audience we were going to address, how much detail we needed to go into, and how many assumptions we needed to make about how much people know about all of this cultural and historical stuff. For me that was a really tricky part of making the movie.

BH: You also interviewed counselors and people involved in directing the program. How was that? How did that experience go? They have a very different perspective.

VS: Yes. It was the same thing, with word of mouth. That’s how we found these people. Dr. Li, the older woman, is pretty famous in Taiwan. She used to be in a big shot in the KMT, which is very rare. Her husband was a big-time politician too. We had to really work a lot of connections for that. I think we must have had two or three different people politely asking her if she’d like to be in the movie–people who had been her student, people who had worked with her in the government, people from the university that was sponsoring the film.

It took of work to get to her interview and I’m really glad we did.

The other guy from the OCAC was a little more open. In terms of accessibility, he was very accessible. He wasn’t quite so hard to get to. But I think that’s just because he’s not as famous.

Dr. Li is quite famous, if you ask older Taiwanese people, particularly KMT people. Her face is in the yearbook. She would give a speech at the beginning of the program and at the end of the program. At the beginning, she would give the speech in English and at the closing of the program, she would do it in Chinese, with the assumption that the students have learned enough Chinese to know what she is saying. It was very optimistic if you ask me. [Laughs]

BH: What about some of the counselors that were on the program you interviewed? It’s very interesting, because actually when you think about it, a lot of counselors were not too much older than the students sometimes. The one that jumped out to me was the one that later moved to America and had Taiwanese American children. That was pretty fascinating, I thought that was a great interview.

VS: Yeah. It was the same thing, all word of mouth. That person might have contacted me on Facebook, because I did a couple of crowdfunding campaigns. So there was a lot of press, especially around the first campaign.

A lot of people wrote to me afterward. They would either say, “I went on the trip,” or “I was a counselor,” or “I met my partner on the trip and we got married.” That was another way that we reached a lot of people, through social media.

But yeah, I think I was interested in finding counselors, especially the one that eventually came to the US, like you said. Because we have a lot of people who had gone on the trip and then moved to Asia. I wanted to show the flip side of that.

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

BH: Looking at the program so many years later, what do you think you would see as the legacy of the program? It was very interesting for me just because, as I mentioned, it’s been massively influential. People are always talking about it. Yet there weren’t actually many attempts at documenting it.

VS: I think for myself and for others, it was such a huge influence—for people here in the States for sure. It impacted a lot of people to varying degrees, even if you only just knew about it.

At one point I know, probably in the 1980s through the 2000s, everybody would know someone who went, or who went themselves. You would say, “Who’s going on Love Boat this year? Oh, I heard like your little sister is going, that kind of thing.” So it was really a big phenomenon.

But the other part that is interesting to me is that it was so well-known among Taiwanese and Chinese Americans. However, outside of those communities, not a lot of people know about it.

Even yesterday I had lunch with some folks and I said, “Well, I made this movie about the Taiwan Love Boat” and the one Asian person in the group said, “Oh yeah, my brother went.” It’s totally random. There’s always going to be like one degree of separation, it seems like.

BH: It seems like there’s no kind of oral history record of that apart from your film or anyone who has written a book on it.

VS: Ellen Wu from Indiana State University wrote her master’s thesis on it, but that was in 1998. There have been articles in various publications, but I don’t think there’s ever been a comprehensive history, per se, that’s up to date. The Wikipedia page is pretty good.

Ben Shyu, I think, is the person who keeps the Wikipedia page and he’s in the movie very briefly. He was one of the people who is super helpful about getting contacts. He’s been like an adviser to the film.

BH: Lastly, in conclusion, what is next for the film? I think at the screening in Taipei last week, you mentioned that it was the third time it’s been shown. What are your plans next for the film and what are your plans next as a director in general?

VS: As a director, I don’t know. I just need to take a nap for a while. It took a really long time to finish. I just feel like I need to enjoy the experience of having finished this film for a while.

And as far as screenings are concerned, we literally just finished the final cut in April about two or three weeks before the first screening. We didn’t have a lot of time to send it out to festivals. But now we’re sending out to different festivals and so there’s going to be a little lag time between the screening that we just had in Taipei and the next show. It probably won’t be until mid-summerish. The film will be in the Asian American International Film Festival in New York City this summer.

Then hopefully there will be a bunch of screenings in the fall. Film festival deadlines are usually a few months ahead of when the screening actually is. I’m sure none of those are announced yet so I’m not allowed to say where it’s going to be.

A lot of people have asked if it is possible to watch it online and that will not happen until after the film festivals are done. Film festivals want you to embargo the film, they don’t want it to be able to be seen online during the festival.

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

Photo credit: Valerie Soe/Love Boat: Taiwan

But I’m hoping it’ll get to be streamed somewhere. That would be great, because I think a lot of people want to watch it.

It would be nice to have some kind of supplementary educational materials, like some kind of Web site or something that that will also add more links—that maybe will explain what the difference between the ROC and Taiwan is or why Taiwan is sometimes called the ROC and sometimes not. Or who are the KMT and why are we talking about that.

So yeah. There’s hopefully opportunities for that, so we’ll be able to have a more in-depth version.

Someone even mentioned wanting somewhere they could put up their own personal memories about being on the trip. I think all of that would be great to see.