Chenhuang Jinju

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless

Translator: Brian Hioe

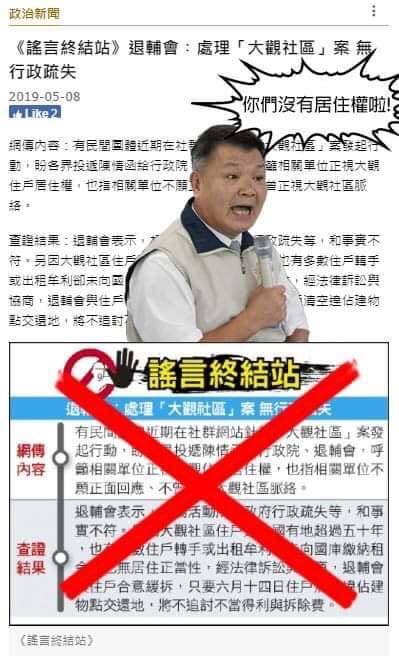

WITH THE DAGUAN Community in Banqiao, New Taipei, it appears that after negotiating with the Veterans’ Affairs Council, they are still unable to avoid the fate of having their homes demolished. The Daguan Self-Help Association and Daguan residents have decided to hold an exhibition which includes poetry, graffiti, and protest memorabilia—to share their recollections of the protest struggle. Before visiting this exhibition, we might look at the Liberty Times’ report, “The Last Stop for Rumors” to criticize the misunderstanding of the suffering faced by Daguan residents in the mainstream media.

Indeed, the “Last Stop for Rumors” is not a place for resolving rumors, but in fact, creates rumors, ignoring the truth about Daguan residents and the Daguan Self-Help Association. “The Last Stop for Rumors” and the Veterans’ Affairs Council see Daguan as a case of administrative oversight, finding fault with that Daguan residents “occupy state-owned property” and seeing them as, in this way, lacking “residential legitimacy.”

But is that really the case? One can trace the history of Daguan Community back to 1956, with its residence by retired military veterans and their family members. This land was only registered as state-owned property by the army command headquarters in 1966.

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless

Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless

What then, is the accusation of “illegally occupying state-owned property” based on? The report does not even mention the expansion of Daguan Road in 1985, requiring the movement of residents’ homes by two meters. Not only did the Veterans’ Affairs Council agree to residents rebuilding their homes, but the Taipei county government also paid residents compensation for the demolition of their homes. One cannot help but ask, why is the legitimacy of residents to live on the land being questioned? Who decides this? “The Last Stop for Rumors” offers no explanation for this.

Is this, then, a matter of administrative oversight? With the negotiation that took place on March 14th, the Veterans’ Affairs Council only provided two choices: 1.) The twenty-one households of Daguan Community sign an agreement for their homes to be demolished, then the Veterans’ Affairs Council will apply for a three month delay in the demolition, will no longer pursue making residents pay for the cost of demolition, the charge of “unjust enrichment”, and will pay twelve of the families 100,000 NT.

What about resettlement, then? The Veterans’ Affairs Council’s deputy committee chair Li Wen-zhong expressed that they would do their best to compromise, but only offered one other option: 2.) If any single resident does not agree to sign the settlement agreeing to the demolition, three days later, the entire neighborhood will be demolished. For each day, there will be 5,000,000 or 6,000,000 NTD in demolition fees that the residents must pay. Which is to say, the Veterans’ Affairs Council is able to decide whether a demolition takes place or not, or to decide whether to pursue charges of “unjust enrichment” or not (the Banqiao Veterans’ Association originally filed a civic charge, but these have become sharp weapons used by bureaucrats, using this unfair treatment as a way to compel residents to agree.)

The residents of Daguan Community and the Daguan Self-Help Organization have, in these past few years, been unceasingly attacked by netizens. They are blamed as these “Mainlanders” who love the KMT, who vote for the KMT, and criticized as to why they don’t protest the KMT, or that they break the law but still dare to raise their voices, that they are irrational, violent, or have reactionary rhetoric.

Response to the Liberty Times from Daguan residents. Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless。

Response to the Liberty Times from Daguan residents. Photo credit: 大觀事件-Daguan Homeless。

As those who have actually spoken to the residents of the village know, the residents of the village are not simply old waishengren, but includes second and third-generation waishengren, benshengren, New Immigrants, and others, not to mention that it is false equivalence to simply assume that waishengren are simply KMT.

Even if many waishengren came to Taiwan with the hope of reunification with China, holding expectations that the Republic of China would be reestablished in China and the CCP overthrown, they see the present-day KMT fawning on China practically every day, with the Republic of China they once pursued having simply become the CCP party-state. Do people really think that these “old waishengren soldiers” have not reflected on the fact that they’ve been betrayed by the KMT and that they still continue to believe in the party-state? Is this not an assumption that Daguan residents have no capacity for thought?

Do residents of Daguan vote for the KMT? As far as the author understands, Daguan residents generally refuse to vote. In a representative governmental system, Daguan residents (as well as the majority of residents of Taiwan) only have the KMT and the DPP as their only choices. Yet these two parties frequently disappoint the people. Under these circumstances, regardless of which party they vote for, they are caught in the “reactive” state of only having two choices. If they decide not to vote, this is a protest against the two-party system; this is not being inactive. This is not political nihilism either, but being proactive, in residents refusing to turn over their voices to the government.

After repeatedly having the words, “breaking the law,” “being irrational,” and “violent” thrown at them, these are words from those who adhere to pacifist ideology and can only throw words from textbooks incessantly at demonstrators. What are the issues with this sort of ideology? To raise an example, after World War II, Freddie Nanda Dekker-Oversteege, her sister, and a friend destroyed a bridge and railroad track, in order to rescue Jews captured by the Nazis, using weapons hidden in their bicycle to kill Nazis. If this form of protest can only be seen as illegal, violent, and irrational, this is to ignore the struggles and suffering of the oppressed.

To raise another example, in the short stories of Bunun author Tuobasi Tamapima, “The Last Hunter,” this is stated even more clearly. The main character of the story, Biyari, simply wishes to follow the hunting lifestyle of his elders, but because the forests and mountains have become state-owned property, the Bunun have lost their traditional territories, hunting ground, and the police accused their activity of being illegal, demanding that they cease hunting and turn over the animals they had hunted. If there is no way to protest or resist this form of colonization, is there any way for Taiwan to become a better democracy?

Tuobasi Tamapima’s “The Last Hunter.” Photo credit: Morning Star Books

Tuobasi Tamapima’s “The Last Hunter.” Photo credit: Morning Star Books

Freud published “Mourning and Melancholia” in 1917, analyzing the relation between the two states. To put it simply, after we have lost our love object, if you can mourn properly, this is more healthy. If you refuse to admit your loss, this causes melancholia. But Freud never described what is a complete process of mourning, yet mourning is something which occurs after a loss.

Daguan’s exhibition questions this timing. The exhibition will serve as a means of mourning before the actual demolition of Daguan, a form of mourning on the precipice of losing everything. This is not only with regards to homes, clothes, neighbors, but also these material objects amalgamated with people’s feelings.

Not only will the exhibit serve as a form of premature mourning, but the people are invited to join in this mourning. June 2nd will not be the last day of mourning, with buildings about to be demolished, but the strength of grieving will not be enough to stop the demolition. If we don’t see our mourning as a pathological structure, mourning can magnify loss, as a form of commitment to mourning: That in the future, we will reflect on the past. [1]

If we understand Heidegger’s Dasein, the precondition for human existence is “there”. But for those forced to move from that “there” by eviction, with a forced migration to the marginal places of the world, if we care about the disprivileged, we should wander on the peripheries of the earth with them, to coexist and co-resist. What else is there to do?

Exhibition Information

- Dates: 5/18 to 6/2

- Time: 13:00~18:00

- Location: Daguan Community (Banqiao, Daguan Road, Section 20, No. 40)

- Facebook Event: https://www.facebook.com/events/2327922057480932/?ti=ia

- Admission: 50 NT

- Daguan is currently selling t-shirts, tote bags, and lighters

- Daguan is also accepting donations at:

Chunghwa Post(700)

Account Number: 00211340197571

Household: Lin Yu-Ting

[1] Moten, Fred. 2003. “Black Mo’nin’” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning, ed. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian. University of California Press.